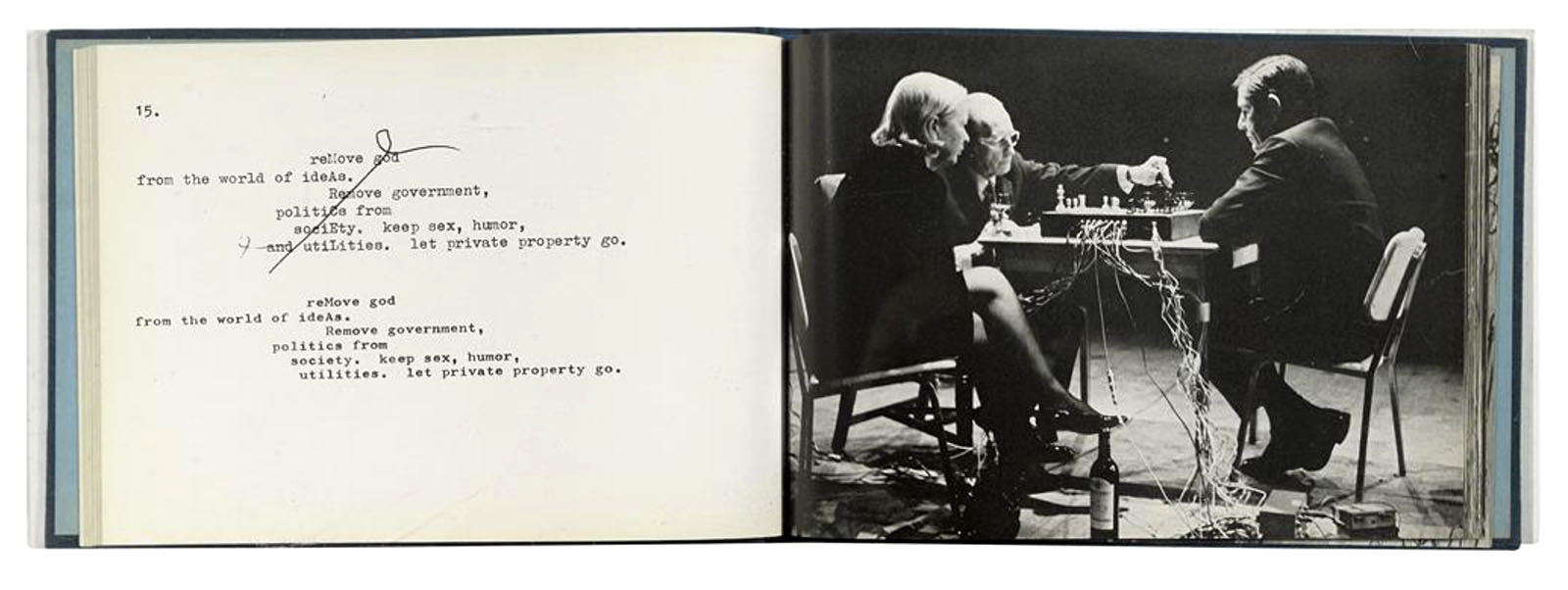

Reunion is an artist’s book by Shigeko Kubota, published by Takeyoshi Miyazawa in 1970. Documenting the March 1968 performance Reunion in Toronto, the book pairs Kubota’s black-and-white photographs of Marcel Duchamp and John Cage playing chess on an electronic chessboard with Cage’s text 36 Acrostics re and not re Duchamp and a blue flexi-disc recording of the event. The flexi-disc represents the only publicly released audio recording of Reunion, a performance in which chess games between Cage and the Duchamps determined the form and spatial distribution of electronic music composed by David Behrman, Gordon Mumma, David Tudor, and Lowell Cross. The event took place on 5 March 1968 at the Ryerson Theatre and turned out to be Marcel Duchamp’s last public appearance before his death seven months later.

Reunion

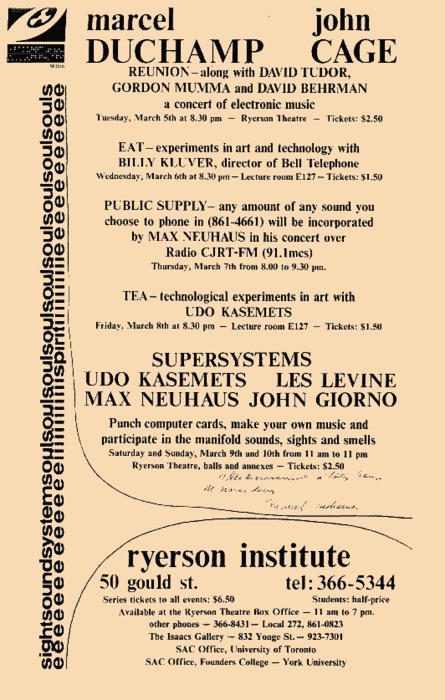

On the evening of 5 March 1968, an audience filled the Ryerson Theatre in Toronto for the opening event of SightSoundSystems, a festival of art and technology directed by the Estonian-born Canadian composer Udo Kasemets and jointly presented by the Isaacs Gallery and Ryerson Polytechnical Institute. The performance that unfolded was Reunion, conceived by John Cage as a piece with no score, in which the moves of a chess game would generate and spatially distribute electronic music around the audience.

Cage had telephoned Lowell Cross, a graduate student and Research Associate in the Electronic Music Studios at the University of Toronto, in late January or early February 1968 to ask him to build an electronic chessboard. Cross initially declined, citing his thesis work. Cage persisted: “Perhaps you will change your mind if I tell you who my chess partner will be.” When Cross agreed to hear, Cage said simply, “Marcel Duchamp.” Cross accepted immediately and began designing the board, completing it only the night before the performance.

Cage told me that he was naming the piece Reunion because he wanted to bring together artists with whom he had been affiliated in the past in a homey but theatrical setting. He and Duchamp would play chess at center stage, and the moves of the game would result in the selection of sound sources and their spatial distribution around the audience.

- Lowell Cross, Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 9, 1999

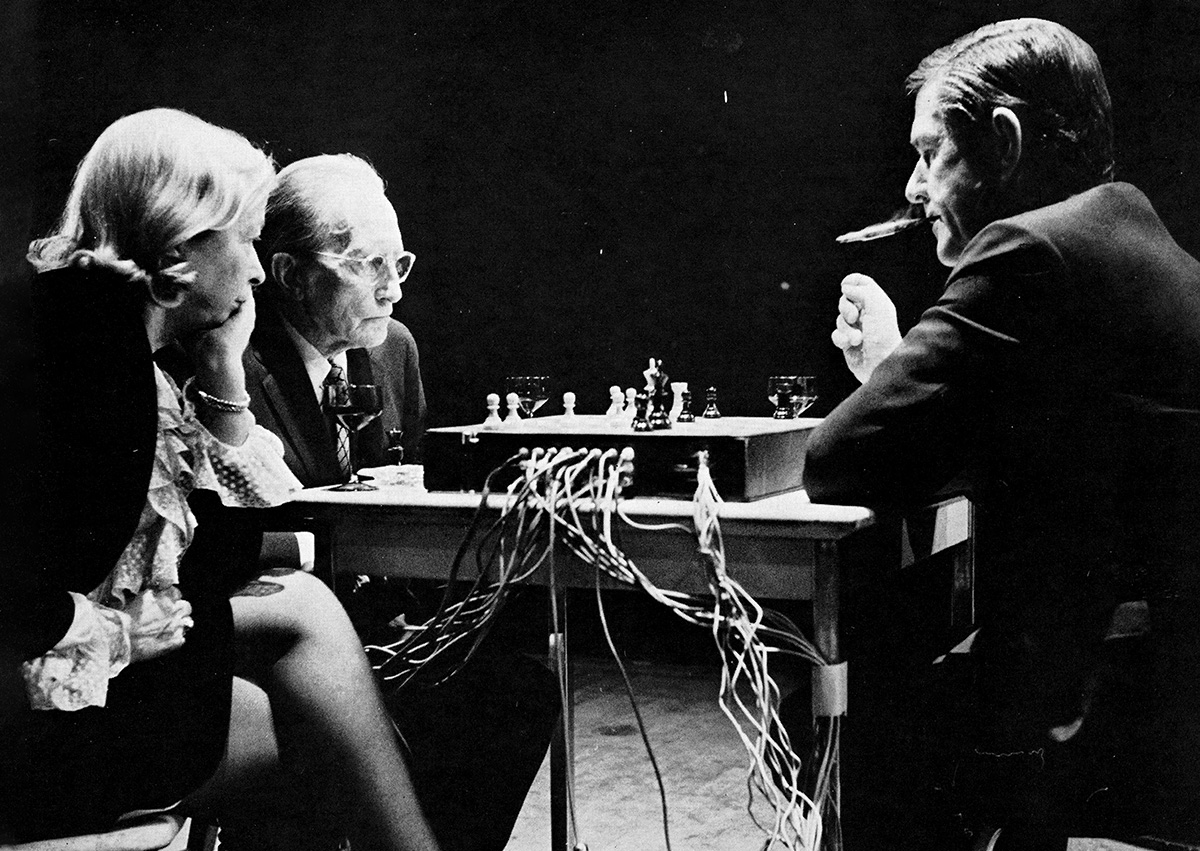

The staging at the Ryerson Theatre deliberately mimicked the setting of Cage’s chess lessons at the Duchamps’ townhouse apartment on West 10th Street in New York. Duchamp sat in a comfortable easy chair while Cage was content with an ordinary kitchen chair. Teeny Duchamp watched nearby. Cross’s modified television screens displayed oscilloscopic images of the sound events passing through the chessboard. Wine was served, and the players smoked throughout, with Duchamp puffing his characteristic cigar and Cage and Teeny smoking cigarettes. Cross, who was responsible for the wine as well as the chessboard, purchased a single bottle of 1964 Château Kirwan from the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, prompting a bemused exchange with the clerk over serving one bottle to a public concert of some 500 attendees.

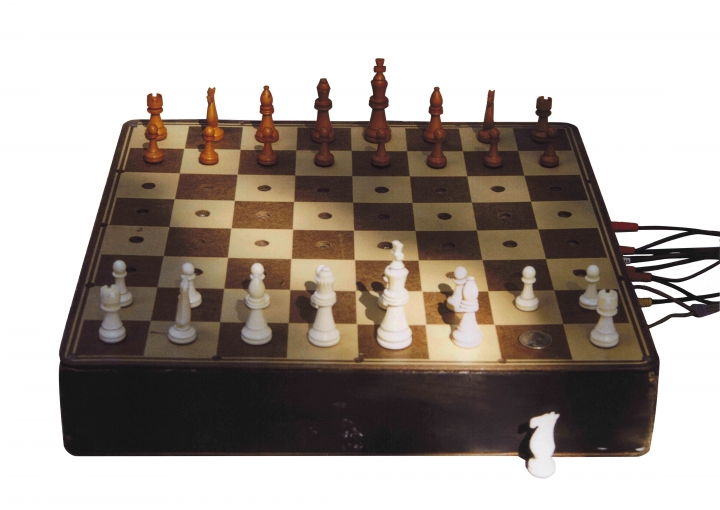

The Chessboard

Cross’s chessboard used a purely resistive matrix of 64 photoresistors, one embedded in the centre of each square, which responded to being covered or uncovered by chess pieces under bright stage lighting. The board had 16 unbalanced audio inputs (four from each of the four collaborating composers) and 8 outputs, each routed to a loudspeaker arranged around the audience at compass points. Before the opening move, the board was effectively silent: the two pairs of ranks where pieces sat at the start did not pass signals when their photoresistors were covered, and the four centre ranks did not pass signals when their photoresistors were exposed.

As the game progressed and pieces moved, the sound environment grew more complex, then diminished as pieces were captured and removed. Cross’s internal wiring was arbitrary and quasi-random: each of the 16 inputs could appear at four of the eight different outputs, though Cross followed no particular plan in making these connections. Additional sonic effects arose from the shadows of the players’ hands and arms passing over the photoresistors as they moved pieces. At Cage’s insistence, nine contact microphones were also mounted inside the board so that the physical sounds of pieces being placed might occasionally be heard, though these registered only as faint thuds even when amplified.

The board was built from two tournament-size Masonite boards separated by painted two-by-fours, measuring 420 × 420 × 77 mm. It could be turned over for a game of ordinary chess. The chessboard is now part of the collection of the John Cage Trust.

The Games

The four collaborating composers performed continuously throughout the evening using their own pre-existing works on custom-built or modified equipment. Behrman contributed Runthrough, Mumma performed Hornpipe and Swarmer, and Tudor, who Cross noted did not enter the engagement with much enthusiasm, performed a piece titled Reunion. Cross’s contributions were two pre-recorded tape works, Video II (B) and Musica Instrumentalis, the latter also generating the oscilloscopic imagery on the television screens.

Duchamp, playing White, gave Cage a handicap in the first game by removing his king’s knight, replacing it on the board with a U.S. quarter dollar. With this action, as Cross later noted, Duchamp demonstrated his understanding of the function of the chessboard - and indeed, of the entire event. Despite the handicap, Duchamp defeated Cage in roughly 25 minutes. In the 1950s, Duchamp had been considered by the American grand master Edward Lasker to be among the top 25 chess players in the United States. He had also competed for France in the 1930s Chess Olympiads alongside Alexander Alekhine.

After a brief intermission during which much of the audience departed, Cage (White) and Teeny Duchamp (Black) began a second game at around 9:15 PM while Duchamp observed or, as photographs by Kubota show, occasionally dozed off. The two proved well matched and played seriously and deliberately. The game continued until 1:00 AM on 6 March, when Duchamp made known his fatigue. The match was adjourned, with Duchamp memorising the final positions. Teeny finished the game and won several days later in New York. No record of the moves in either game survives.

Among those in the audience was Marshall McLuhan, then at the height of his fame at the University of Toronto. Cross was a student in McLuhan’s seminar “Media and Society” that academic year. According to Kasemets, McLuhan stayed for the first game and left immediately after.

Reception and Later Performances

Toronto newspaper critics were uniformly hostile. William Littler of the Star called the event “mighty boring,” while his colleague Robert Fulford found it “infinitely boring” and an example of “total non-communication, all around.” Kenneth Winters of the Telegram wrote that the visitors were “just about sufficiently fossilized for reverent immurement in a university.” The editors of the Globe and Mail did not send a reporter.

Two additional performances of Reunion took place that spring. At the Electric Circus in New York, the Duchamps declined to participate; Cage’s chess partner was the editor of The Saturday Evening Post. No wine was served, but margaritas were prepared by Cage’s friend Jean Rigg, with a contact microphone attached to the blender. At Mills College in Oakland, California, Cross played against Cage and lost after a bold opening variation.

The Book

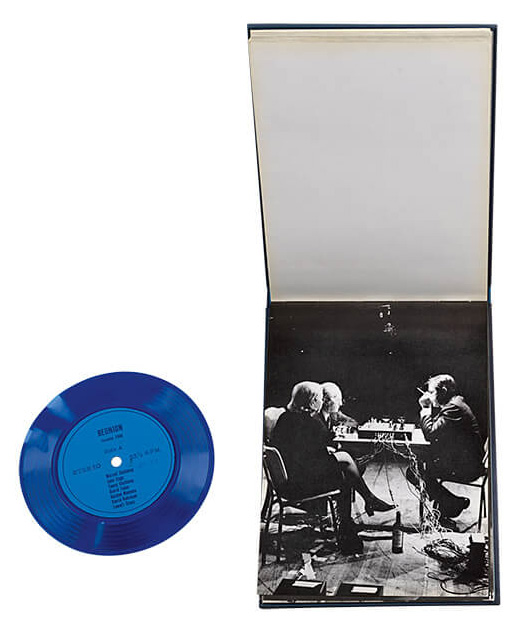

Shigeko Kubota, a Japanese-born artist affiliated with Fluxus who had met Duchamp earlier in 1968, photographed the Reunion performance. Her black-and-white photographs of the event, showing Duchamp and Cage at the board, Teeny observing, and the composers at work, became the basis for the artist’s book Marcel Duchamp and John Cage.

Published in 1970 by Takeyoshi Miyazawa, then chief editor of the Japanese art magazine Bijutsu Techo, the book was issued in a limited edition of 500 hand-numbered copies. It is bound in blue cloth with silver lettering, housed in a clear acetate dust jacket and a blue cardboard slipcase. The photographs appear on rectos, with Cage’s text 36 Acrostics re and not re Duchamp printed on the facing versos. This text, a set of poems in the mesostic form, carries the instruction: “A given letter capitalized does not occur among the letters between it and the preceding capitalized letter.”

A blue 33⅓ rpm flexi-disc containing a recording of the Reunion performance is laid into the book. This flexi-disc constitutes the only commercially distributed audio document of the event. Although the entire performance was also recorded by CBS/Columbia with David Behrman as producer, the location and condition of those tapes are unknown. Cross’s tape work Video II (B), heard during Reunion, was separately released on Source Records No. 5 in 1971.

According to the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation, the book was funded by Kubota herself and was not intended for sale, which accounts for its limited distribution. Kubota later reworked the photographs into two additional artworks: Marcel Duchamp and John Cage (1972), a single-channel videotape incorporating footage of Cage alongside the colourised photographs and footage from Kubota’s 1972 visit to the Duchamp family graveyard in Rouen; and Video Chess (1968–75), a video sculpture consisting of a transparent chessboard placed over a face-up television monitor playing the transferred and colourised images.

Audio

Duchamp’s Last Appearance

Marcel Duchamp died on 2 October 1968 at his apartment in Neuilly-sur-Seine, seven months after Reunion. Apart from a brief curtain call with Merce Cunningham and Dance Company in Buffalo, New York on 10 March 1968, the performance at the Ryerson Theatre was his final public appearance. As Cross would later write, Duchamp played his role as chess master that evening with quiet dignity, as though the event was nothing more than what it was intended to be: a part of everyday life.

Explore the Book

This is a preview only - view fullsize on archive.org

Gallery