Cybernetic Serendipity - The Computer and the Arts is a special issue of the British magazine Studio International, first published in July 1968 to coincide with the exhibition of the same name at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. Curated by Jasia Reichardt at the suggestion of the German philosopher Max Bense, the exhibition was the first large-scale international show devoted to the relationship between computers, cybernetics, and creative activity, drawing an estimated 45,000 to 60,000 visitors and subsequently touring to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and the newly opened Exploratorium in San Francisco.

Background

The origins of the exhibition can be traced to 1965, when Max Bense visited the ICA during a concrete poetry exhibition curated by Reichardt. When she asked what she should do next, Bense’s reply was direct: she should look into computers. It was a timely suggestion. Only months earlier, on 5 February 1965, Bense had opened what is now considered the first exhibition of computer-generated art at his Studiengalerie at the Technische Hochschule in Stuttgart, showing plotter drawings by Georg Nees. Computer graphics had also been exhibited that year in New York. The field was new enough that its practitioners were almost exclusively scientists and engineers rather than trained artists - a fact that would become one of the exhibition’s most interesting features.

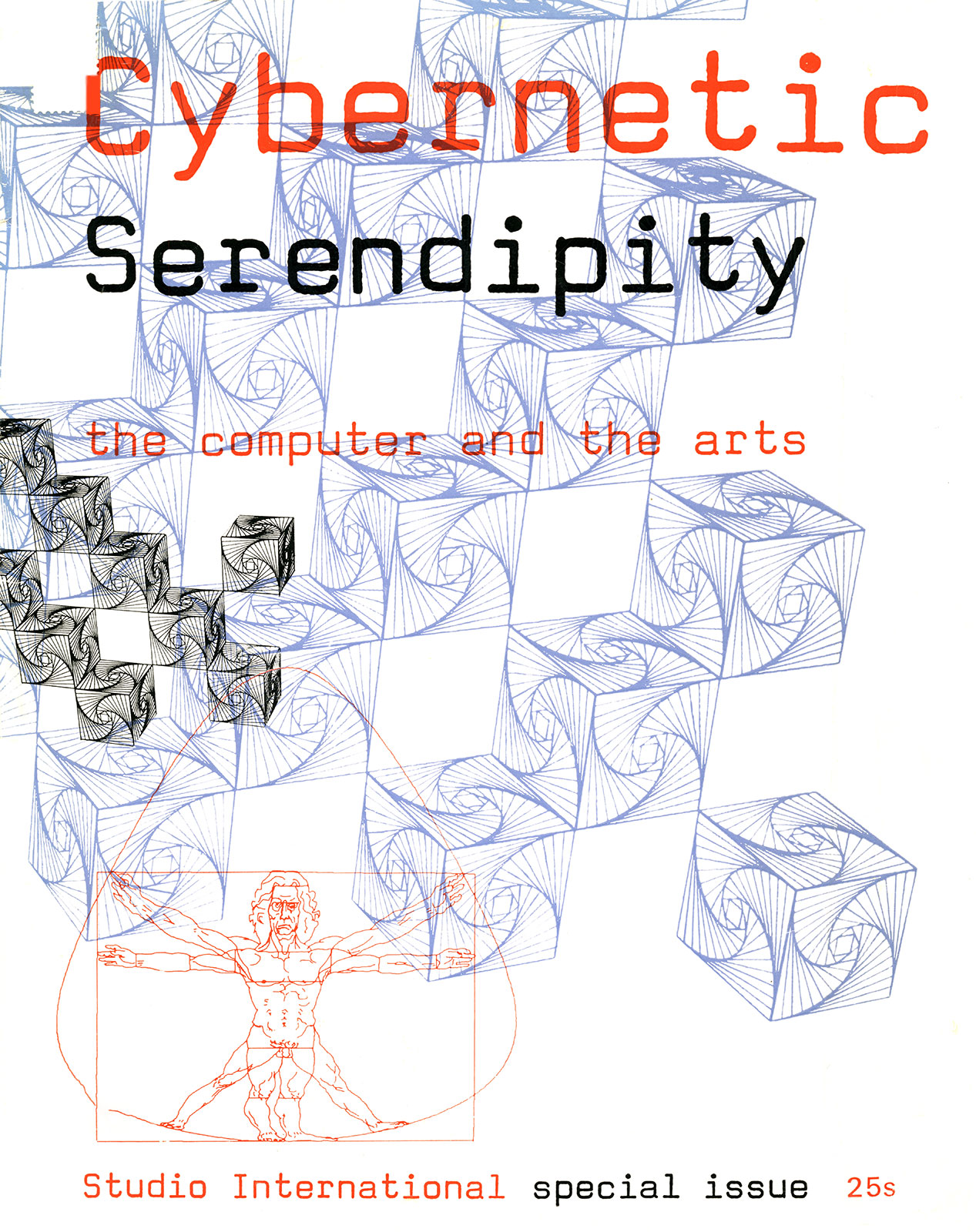

Reichardt, who served as Assistant Director of the ICA from 1963 to 1971, began planning the project in autumn 1965. It took three years to secure adequate financial support. She was assisted by Mark Dowson, a freelance electronics and systems design consultant associated with Dr. Gordon Pask and System Research Ltd., who served as technological adviser; Peter Schmidt, a painter with a particular interest in electronic and computer music, as musical adviser; and Franciszka Themerson - the Polish-born London-based painter, illustrator, and theatrical designer - who designed both the exhibition itself and the celebrated catalogue cover. Students from the Bath Academy of Art assisted Themerson with the exhibition installation.

The title paired cybernetics - from the Greek kybernetes, meaning steersman, a term first used by Norbert Wiener in 1948 to describe systems of communication and control in complex electronic devices - with serendipity, a word coined by Horace Walpole in 1754 after a legend about three princes of Serendip (the old name for Ceylon) who, in their travels, always found something better than what they were looking for. Through the use of cybernetic devices to make graphics, film, and poems, as well as randomising machines that interacted with the spectator, many such happy discoveries were made.

Exhibition

Cybernetic Serendipity opened at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Nash House, The Mall, London, on 2 August 1968 and ran until 20 October. The exhibition was opened by Tony Benn, then Minister of Technology under Harold Wilson’s Labour government - a fitting political patron for a show staged during what Wilson had promised would be a Britain “forged in the white heat” of technological revolution. Estimates of total visitors ranged from 44,000 to 60,000, though the ICA did not maintain precise counts. The Evening Standard captured the show’s ecumenical appeal by asking where else in London one could take “a hippy, a computer programmer, a ten-year-old schoolboy and guarantee that each would be perfectly happy for an hour.”

The exhibition brought together approximately 325 participants from many countries: an estimated 43 artists, composers, and poets alongside 87 engineers, computer scientists, and philosophers, with the rest comprising technicians and other contributors. It was organised into three sections:

- Computer-generated graphics, computer-animated films, computer-composed and -played music, and computer poems and texts

- Cybernetic devices as works of art, cybernetic environments, remote-control robots, and painting machines

- Machines demonstrating the uses of computers and an environment dealing with the history of cybernetics

The idea behind this venture… is to show some of the creative forms engendered by technology. The aim is to present an area of activity which manifests artists’ involvement with science, and the scientists’ involvement with the arts; also, to show the links between the random systems employed by artists, composers and poets, and those involved with the making and the use of cybernetic devices.

Cybernetic Serendipity deals with possibilities rather than achievements… [t]here are no heroic claims to be made because computers have so far neither revolutionized music, nor art, nor poetry, in the same way that they have revolutionized science.

…no visitor to the exhibition, unless he reads all the notes relating to all the works, will know whether he is looking at something made by an artist, engineer, mathematician, or architect. Nor is it particularly important to know the background of the makers of the various robots, machines and graphics - it will not alter their impact, although it might make us see them differently.

- Jasia Reichardt, exhibition catalogue introduction

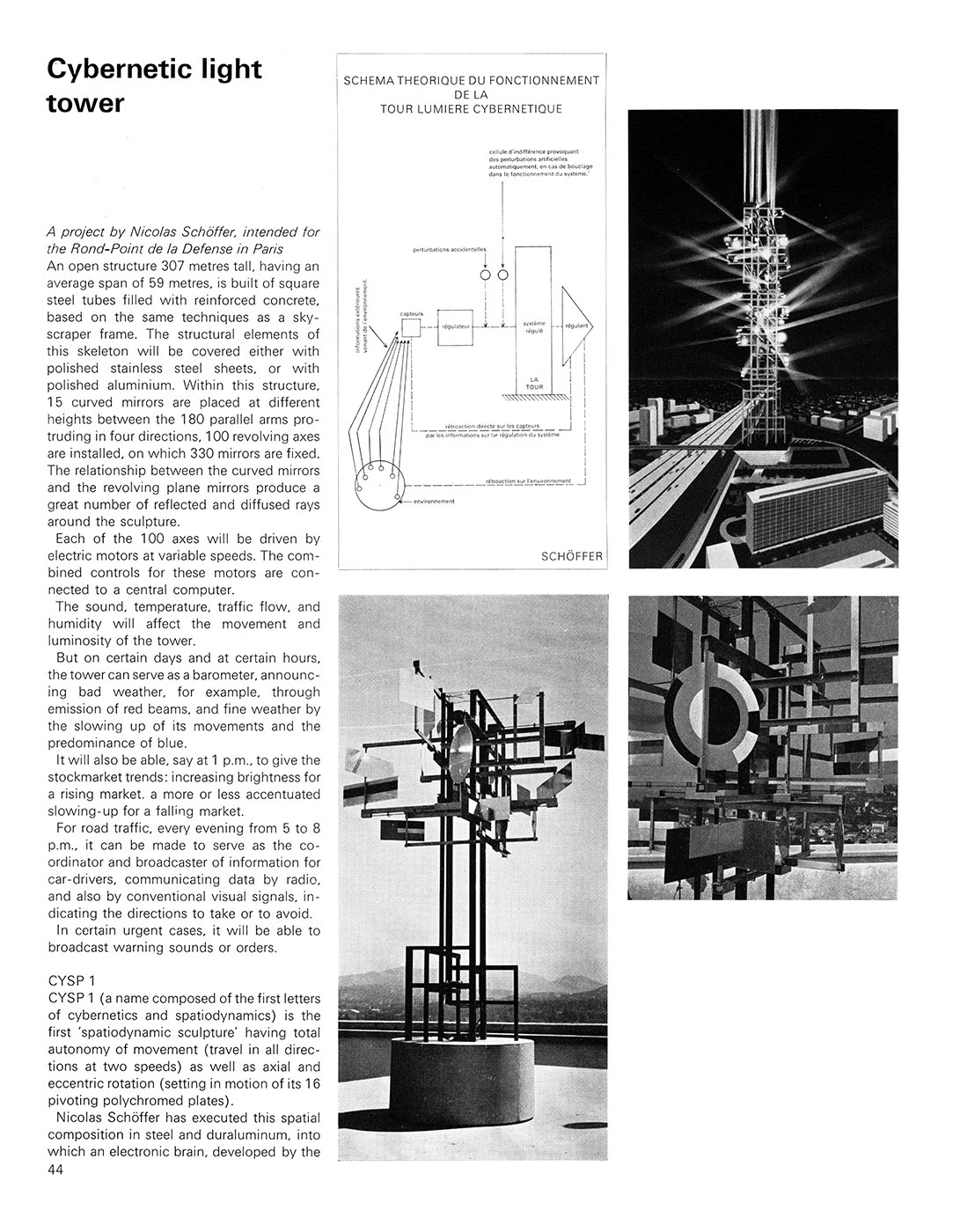

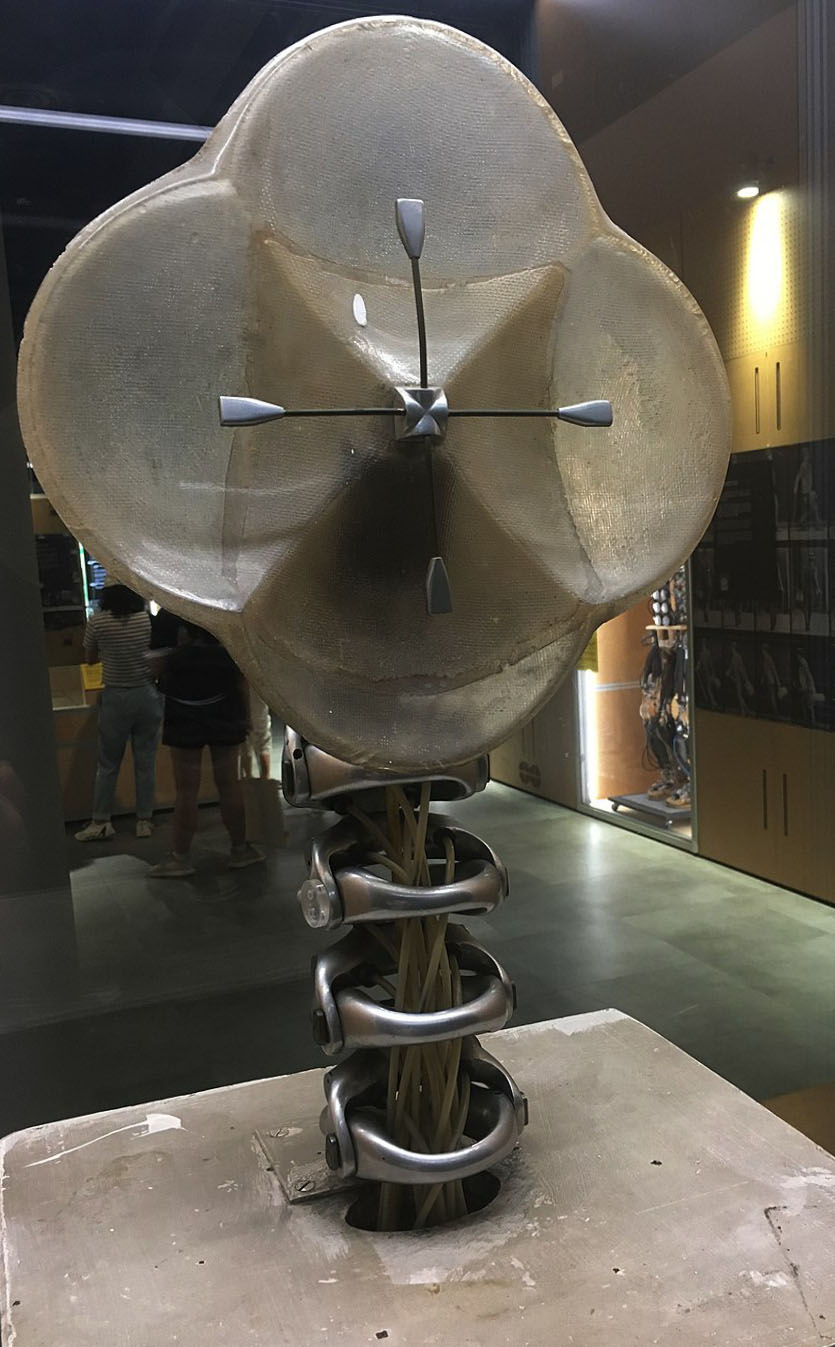

Among the participants were Nicolas Schöffer, who exhibited his Cybernetic Light Tower; Gordon Pask, whose Colloquy of Mobiles (1968) consisted of large interacting mobiles that allowed viewers to join the conversation; Jean Tinguely, who showed two of his painting machines; Nam June Paik, represented by Robot K-456 and televisions with distorted images; Edward Ihnatowicz, whose biomorphic hydraulic Sound Activated Mobile (SAM) turned toward sounds made by visitors in a remarkably lifelike manner; Bruce Lacey, who contributed his radio-controlled robots including ROSA BOSOM; and Wen-Ying Tsai, who presented interactive cybernetic sculptures of vibrating stainless-steel rods with stroboscopic light and audio feedback control. Peter Zinovieff lent part of his studio equipment, allowing visitors to sing or whistle a tune into a microphone, which his equipment would then use to improvise a piece of music. Several machines drew patterns that visitors could take away, or involved them in games.

Other participants included Max Bense, Nicholas Negroponte, Earle Brown, John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, Liliane Lijn, Gustav Metzger, Charles Csuri, the Computer Technique Group of Japan, and A. Michael Noll of Bell Telephone Laboratories, who exhibited a well-known experiment in which he had analysed a 1917 Mondrian painting and produced random computer graphics using the same compositional parameters - the majority of viewers preferred the computer version and misidentified the Mondrian as machine-made.

A scaled-down version of the exhibition subsequently toured to the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Corcoran Annex) in Washington, D.C., from 16 July to 31 August 1969, and to the newly opened Exploratorium in San Francisco from 1 November to 18 December 1969. Several pieces were purchased by the Exploratorium in 1971, some of which remained on display for decades. Remaining exhibition materials were transferred to the Kawasaki City Museum in Japan when Reichardt left the ICA in 1971.

Legacy

The exhibition proved to be a catalyst for institutional developments in computer art. The Computer Arts Society (CAS) was founded in 1968 by three individuals closely connected to the show - cybernetician George Mallen, ICL programmer Alan Sutcliffe (both participants in the exhibition), and architect John Lansdown. Operating as a special interest group of the British Computer Society, CAS fostered computer arts activity through exhibitions, workshops, and its bulletin PAGE, initially edited by Gustav Metzger, another exhibitor at Cybernetic Serendipity.

In 2014, the ICA held a retrospective documentation exhibition, Cybernetic Serendipity: A Documentation, with documents, photographs, press reviews, and a discussion featuring Peter Zinovieff. The Victoria and Albert Museum marked the 50th anniversary in 2018 with Chance and Control: Art in the Age of Computers, which included many works by artists from the original show.

Exhibition Catalogue

The catalogue took the form of a special issue of Studio International magazine, numbering just over 100 pages with approximately 300 images. The first edition was published in July 1968; a revised second edition appeared in September of the same year. The cover was designed by Franciszka Themerson, incorporating computer graphics from the exhibition. The colour frontispiece reproduced a computer graphic by John C. Mott-Smith, made by time-lapse photography successively exposed through coloured filters of an oscilloscope connected to a computer. Laid into copies of the special issue were four separate leaves entitled “Cybernetic Serendipity Music,” each providing a programme for one of eight tapes of music played during the show - information apparently not available in time to be included in the printed issue.

In 1969, Frederick A. Praeger Publishers of New York and Washington, D.C. issued a cloth-bound edition with a dust jacket adapted from the original Studio International cover, likely coinciding with the exhibition’s showing at the Corcoran Gallery. The Praeger edition included an index and contained numerous revisions and changes from the 1968 text. A reprint was issued by Studio International Foundation in 2018 to mark the exhibition’s 50th anniversary.

The catalogue is organised into sections dedicated to the connections between the computer and music, dance, poetry, painting, film, architecture, and graphics. It includes a glossary, a bibliography, and contributions from cybernetics originator Norbert Wiener, musicians Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage, and a range of individuals involved in the cybernetic movement, alongside photographic and written documentation of the exhibited creations.

Selected Essays

Cybernetic Serendipity is an international exhibition exploring and demonstrating some of the relationships between technology and creativity.

The idea behind this venture, for which I am grateful to Professor Max Bense of Stuttgart, is to show some of the creative forms engendered by technology. The aim is to present an area of activity which manifests artists’ involvement with science, and the scientists’ involvement with the arts; also, to show the links between the random systems employed by artists, composers and poets, and those involved with the making and the use of cybernetic devices.

The exhibition is divided into three sections, and these sections are represented in the catalogue in a different order:

- Computer-generated graphics, computer-animated films, computer-composed and -played music, and computer poems and texts

- Cybernetic devices as works of art, cybernetic environments, remote-control robots and painting machines

- Machines demonstrating the uses of computers and an environment dealing with the history of cybernetics.

Cybernetic Serendipity deals with possibilities rather than achievements, and in this sense it is prematurely optimistic. There are no heroic claims to be made because computers have so far neither revolutionized music, nor art, nor poetry, in the same way that they have revolutionized science.

There are two main points which make this exhibition and this catalogue unusual in the contexts in which art exhibitions and catalogues are normally seen. The first is that no visitor to the exhibition, unless he reads all the notes relating to all the works, will know whether he is looking at something made by an artist, engineer. mathematician, or architect. Nor is it particularly im portant to know the background of the makers of the various robots, machines and graphics-it will not alter their impact, although it might make us see them differently.

The other point is more significant.

New media, such as plastics, or new systems such as visual music notation and the parameters of concrete poetry, inevitably alter the shape of art, the characteristics of music. and the content of poetry. New possibilities extend the range of expression of those creative people whom we identify as painters. film makers, composers, and poets. It is very rare, however, that new media and new systems should bring in their wake new people to become involved in creative activity, be it composing music, drawing, constructing or writing.

This has happened with the advent of computers. The engineers for whom the graphic plotter driven by a computer represented nothing more than a means of solving certain problems visually, have occasionally become so interested in the possibilities of this visual output, that they have started to make drawings which bear no practical application, and for which the only real motives are the desire to explore, and the sheer pleasure of seeing a drawing materialize. Thus people who would never have put pencil to paper, or brush to canvas, have started making images, both still and animated, which approximate and often look identical to what we call ‘art’ and put in public galleries.

This is the most important single revelation of this exhibition.

Work on this project started in the autumn of 1965. Only by 1968, however, was there enough financial support for it to go ahead. Since the project involves computers, cybernetics, electronics, music, art, poetry, machines, as well as the problem of how to present this hybrid mixture, I could not have done it on my own.

I was very lucky to have had the help and advice of: technological adviser - Mark Dowson, freelance electronics and system design consultant, associated with Dr. Gordon Pask and System Research Ltd. music adviser - Peter Schmidt, painter, who has a particular interest in electronic and computer music and who has composed music himself. exhibition designer - Franciszka Themerson, FSIA, OGG College de Pataphysique (Paris), painter and theatrical designer.

Jasia Reichardt

Robots and computers have been with us for a long time. The first computers were the abacus used thousands of years ago; the first robot (in myth, if not reality) the Golem, a man made of clay by the High Rabbi Lev Ben Bezalel of Prague in the sixteenth century. This is also the first cautionary tale about robots; for the Golem. animated by a slip of paper bearing the name of God. stuck to its forehead. turned on the Rabbi and kil led him when he made it work on the Sabbath. The word ‘robot’ comes to us from the Czech writer Karel Capek and his play, R.U.R. (Russums Universal Robots) of 1928. Meanwhile computers had been developing steadily; the first adding machine was Pascal’s calculator, 1642, followed closely by Leibniz’s calculating machine which could multiply, divide and extract roots. Automation started with Jacquard’s punch-card-controlled loom (1801) and, of course, fair ground organs controlled on a similar principle.

The first computer in the modern sense of a machine whose operations are controlled by its input, would have been Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine (c .1840) had he completed it, but we must wait till this century and Bush’s Differential Analyser (1927) for the first working example of this type of machine. The Second World War gave a spur to the development of servomechanisms and electronic computation and saw the creation of the first stored-programme digital electronic computer, ENIAC.

Cybernetics was born officially in 1948 with the publication of Wiener’s book - ‘Cybernetics,’ or ‘Control and communication in the animal and the machine.’ A year later, Shannon’s paper, ‘A mathematical theory of communication,’ consolidated the foundations of cybernetics as we know it today.

A list of a few significant events and their dates: 1642 Pascal’s calculator was built 1673 Leibniz builds his calculating machine 1801 Jacquard’s punch-card-controlled loom 1840 Babbage working on his Analytical Engine 1868 Maxwell publishes his theoretical analysis of Watt’s governor 1927 Bush constructs his Differential Analyser 1944 ENIAC constructed 1946 First Josiah Macy Foundation conference on Cybernetics 1948 Norbert Wiener’s book Cybernetics published 1949 Shannon publishes his paper ‘The mathematical theory of communication’ 1956 First congress of the International Association of Cybernetics at Namur, Belgium.

Since the early 1950’s the pace of work on cybernetics has been so intense and the rate of new discoveries so fast that time alone will tell which events will prove to have been crucial in the development of this still relatively young science.

Mark Dowson

‘Absolute power will corrupt not only men but machines’. In his article ‘Inventing the future’, Dennis Gabor put forward some of his expectations and fears about the function of the machine in society of the future. The above comment was made with reference to electronic predictors, which, having built up a reputation for accuracy, become aware of their infallibility (since they are learning machines) and begin to use their newly-discovered power.

So far electronic predictors have not become a reality. However, another postulation made by Professor Gabor in the same article (Encounter May 1960) appears to be very relevant indeed. Will the machine—he wondered-cut out the creative artist? ‘I sincerely hope’, Gabor continued, ‘that machines will never replace the creative artist, but in good conscience I cannot say that they never could.’

The computer performs various functions which in the broader sense seem to be the act of intelligence, i.e. manipulation of symbols, processing of information, obeying complex rules and even learning by experience. Nevertheless, the computer is not capable of making abstractions, and is devoid of the three prime forces behind creativity-imagination, intuition and emotion. Despite this, the computer as a budding artist has been making an appearance since about 1960. In 1963, the magazine Computers and Automation announced a computer art contest which has been held annually ever since. The winning design usually appears on the cover of the August issue and the runners-up are given a coverage inside. The designs vary considerably although they share certain characteristics, i.e. they are only in black and white, there is an emphasis on geometrical shapes, and they are basically linear. As designs, the computer products look bare and minimal and represent little else than the initial stage in what may be a far more challenging adventure in merging rather than relating creative activity with technology.

Computer graphics range from static compositions to frames of motion pictures, and could be divided into two main categories; 1. those which approximate to pure design or art; and 2. those which are not made with any aesthetic end in view but which serve to visualise complex physical phenomena.

At a conference dealing with computers and design in 1966 at the University of Waterloo, two statements were made which might at first have appeared unnecessarily boastful and heroic: 1. ‘The computer simply elevates the level of possible creative work’. 2. ‘The computer can handle some elements of creativity now-by current definitions of creativity’. Both these statements were made by scientists, although there exists a considerable scepticism amongst scientists as well as artists about the validity of the various experiments in this area. Others claim that the computer provides the first real possibility of a collaboration between the artist and the scientist which can only be based on each other’s familiarity with both media.

The first commercial computer was marketed in 1950. Ten years later the Boeing airplane company coined the term ‘computer graphics’. They used graphics for purely utilitarian purposes. These were employed, for instance, to verify the landing accuracy of a plane viewed from the pilot’s seat and the runway. They were used to establish the interaction of range of movements of the pilot in his environment of the cockpit. To this end they created a 50 percentile pilot and studied him in animation. All the drawings and the animation were done with a computer. Other experiments included visualising acoustic graphs in perspective and the production of very accurate isometric views of aeroplanes.

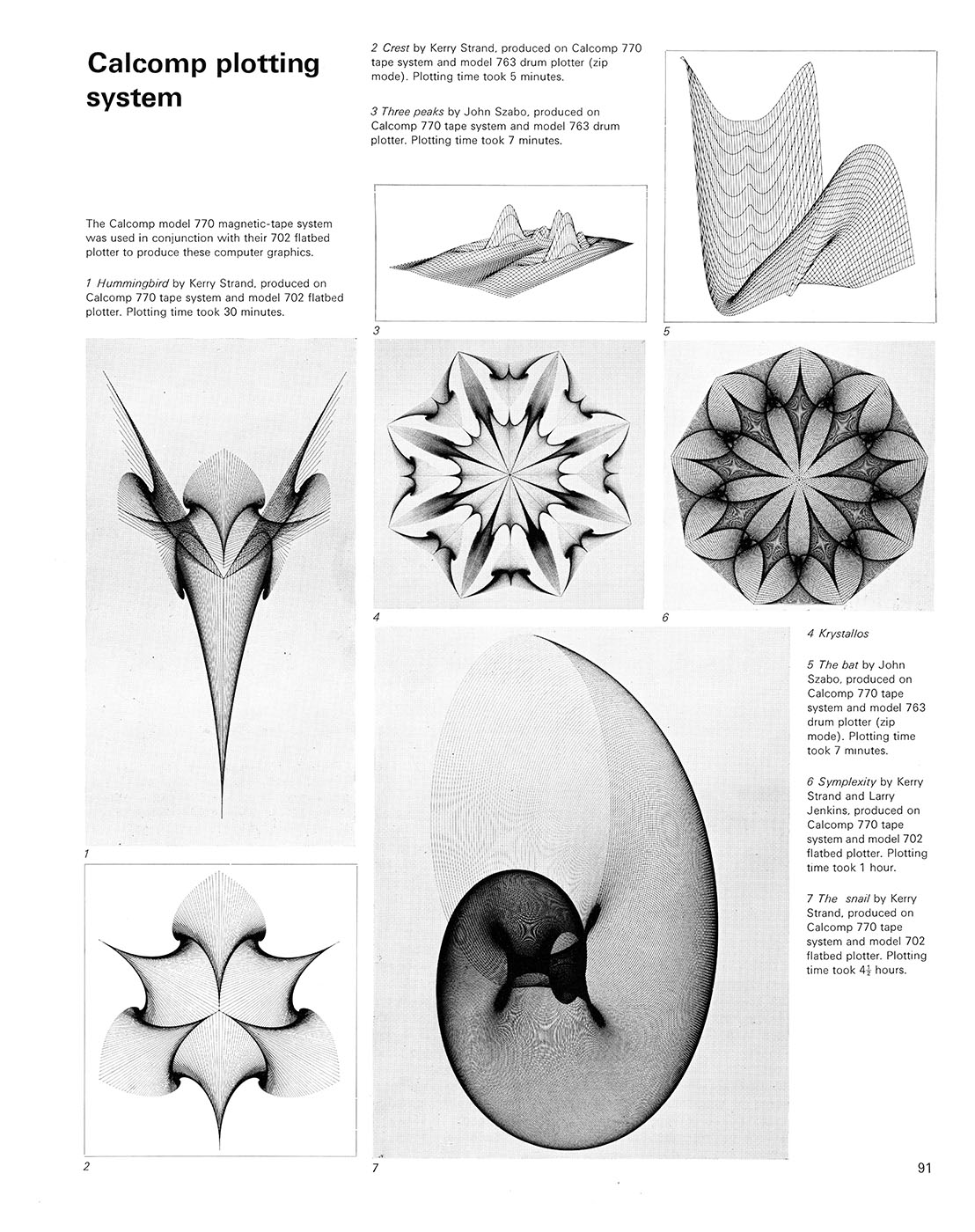

There are two main methods at present by which computer graphics are made. In the first place there are the ink drawings produced by a computer-driven plotter. The plotter, a moving pen, conveys the image direct to paper. Drawings can also be made with the images composed of different letters or figures and printed out on a typewriter which is automatically operated by the computer. In the second category are the computer graphics made on the cathode ray tube with an electron beam electrically deflected across the phosphorescent screen to produce the desired picture. A camera photographs the image in various stages and an electronic console is used to control the picture and to advance the film. Static graphics can be obtained by making enlarged photographs from the film. Whether the pictures are made for analytical purposes or just for fun, the computer graphic is a visual analogue to a sequence of calculations fed into the computer.

The now ‘antique’ Sketchpad which has been used for numerous experiments of this type at Massachusetts Institute of Technology since 1962, was one of the first to produce drawings on a cathode ray tube demonstrating the sort of possibilities which are inherent in the system. One could draw with a light pen on the screen simple patterns consisting of lines and curves. The operator could impose certain constrictions on the patterns he was making by demanding, for instance, by pushing the appropriate button, that the lines be made parallel, vertical or straight. At that stage the operator could not demand something as complex as a solution to the following problems: ‘These lines represent a piece of structure of a certain thickness and size and with certain cross-section characteristics, made of a particular material and obeying specific physical laws-depict this under a stress of so many pounds per cubic foot’.

Today the process whereby a design is adjusted at any stage of its development is already quite familiar. If the operator alters the design on the cathode ray tube with a light pen, the computer converts the altered design into electronic impulses using them to modify the pre-existing programme held in the computer’s memory store. The altered design then appears on another cathode ray tube. This system is widely used by General Motors for car body design. The image on the cathode ray tube can be shifted, rotated, enlarged, seen in perspective, stored, recalled and transferred to paper with the intermediate stages recorded on film. Since the process suggests inhibiting difficulties to someone who is not an electronic engineer, it may be difficult for an artist to imagine how he could possibly make use of a computer. The solution to the problem lies in collaboration. There are three stages in the process of producing computer graphics, or for that matter using the computer in most cases. In the first place the communicator presents his ideas or message which is to be communicated to the computer. Secondly, the communication specialist decides, unless there are specific instructions, whether the problem should be solved graphically, verbally or as a combination of both. Thirdly, the computer specialist selects the appropriate computer equipment and interprets the problem into machine language, so that the computer can act upon it. The Korean artist Nam June Paik has gone so far as to claim that in the same way that collage technique replaced oil paint, so the cathode ray tube will replace canvas. However, so far only three artists that I know of have actually produced computer graphics, the rest to date having been made by scientists.

At the moment the range of visual possibilities may not seem very extensive, since the computer is best used for rather more schematic and geometric forms, and those patterns and designs which are logically simple although they may look very intricate. One can programme the computer to produce patterns based on the golden section or any other specific premise, defining a set of parameters and leaving the various possibilities within them to chance. In this way certain limitations are provided within which the computer can ‘improvise’ and in the space of 20 minutes race through the entire visual potential inherent in the particular scheme. Programmed to draw variations with straight lines it is conceivable, though perhaps unlikely, that one of the graphics produced may consist simply of one line placed exactly on top of another. If there is no formula for predicting each number or step in a given sequence, the system by which this type of computer graphic comes about can be considered random.

Interesting results can be obtained by introducing different random elements into the programme. One can, for instance, produce a series of points on a surface which can be connected in any way with straight lines, or one can instruct the computer to draw solid geometric shapes without specifying in what sequence they are to be superimposed, leaving the overlapping of the shapes to chance.

A fascinating experiment was made by Michael Noll of the Bell Telephone Laboratories whereby he analysed a 1917 black-and-white, plus-and-minus picture by Mondrian and produced a number of random computer graphics using the same number of horizontal and vertical bars placed within an identical overall area. He reported that 59% of the people who were shown both the Mondrian and one of the computer versions preferred the latter, 28% identified the computer picture correctly, and 72% thought that the Mondrian was done by computer. The experiment is not involved either with proof or theory, it simply provides food for thought. Noll, who has produced a considerable number of computer graphics and animated films in America, sees them as a very initial stage in the possible relationship between the artist and computer. He does not consider himself as an artist by virtue of his graphic output. He sees himself as someone who is doing preliminary explorations in order to acquaint artists with these new possibilities.

Perhaps even less credible than the idea of computer-generated pictures is the idea of computer sculpture. That too has been achieved. A programme for a three-dimensional sculpture can be fed into a computer- the three-dimensional projection of a two-dimensional design. It can be transferred via punched paper tape to a milling machine which is capable of producing the physical object in three dimensions.

The computer is only a tool which, at the moment, still seems far removed from those polemic preoccupations which concern art. However, even now seen with all the prejudices of tradition and time, one cannot deny that the computer demonstrates a radical extension in art media and techniques. The possibilities inherent in the computer as a creative tool will do little to change those idioms of art which rely primarily on the dialogue between the artist, his ideas, and the canvas. They will, however, increase the scope of art and contribute to its diversity.

Jasia Reichardt

In her introduction, Reichardt identified what she considered the most important revelation of the exhibition: that the computer had brought entirely new people into creative activity. Engineers for whom the graphic plotter had been nothing more than a problem-solving tool had become so interested in the possibilities of its visual output that they began making drawings with no practical application, motivated only by the desire to explore and the pleasure of seeing a drawing materialise. People who would never have put pencil to paper had started making images - both still and animated - that approximated and often looked identical to what is conventionally called art.

Mark Dowson’s notes on cybernetics sketched a concise history of the field, from the abacus through Pascal’s calculator (1642), Leibniz’s calculating machine (1673), Jacquard’s punch-card-controlled loom (1801), and Babbage’s unfinished Analytical Engine (c.1840) to Bush’s Differential Analyser (1927) and the construction of ENIAC in 1944. Cybernetics was officially born, Dowson wrote, with the publication of Wiener’s Cybernetics in 1948 and consolidated by Shannon’s A Mathematical Theory of Communication the following year.

Reichardt’s essay on computer art surveyed the state of the field with characteristic caution. She quoted Dennis Gabor’s half-hopeful, half-fearful speculation from 1960 about whether machines would one day replace the creative artist, and noted that while the computer could perform functions that in a broad sense seemed intelligent - manipulating symbols, processing information, obeying complex rules, even learning by experience - it remained incapable of making abstractions and was devoid of imagination, intuition, and emotion. She traced the development of computer graphics from Boeing’s coining of the term in 1960, through MIT’s Sketchpad experiments, to General Motors’ use of cathode ray tube design systems. The Korean artist Nam June Paik, she noted, had gone so far as to claim that in the same way collage had replaced oil paint, the cathode ray tube would replace canvas - though at the time of writing she knew of only three artists who had actually produced computer graphics, the rest having been made by scientists. The computer, she concluded, was only a tool that still seemed far removed from the concerns of art, but even seen through the prejudices of tradition and time, one could not deny that it demonstrated a radical extension in art media and techniques.

Explore the Catalogue

This is a preview only - view fullsize on archive.org

Vinyl LP

|

|

| Cybernetic Serendipity Music | |

| Publisher | Institute of Contemporary Arts, London |

|---|---|

| Publishing date | 1968 |

| Format | Vinyl |

| Duration | 52:44 |

A vinyl LP was released by the ICA to accompany the exhibition. The record reflected the prominence of music in the show and was conceived, as the liner notes explained, as “essentially a reportage of current trends and developments in programmed and stochastic music.” During the preparation of the exhibition, two things had become apparent: that showing the state of computer music required including material not strictly composed with or played by computer, and that in such an exploratory field, attempts at historical perspective or firm evaluation were premature.

The first landmark in computer composition is Lejaren A. Hiller’s Illiac Suite, 1957. Many experiments have been carried out before, but these were either exploratory without yielding a tangible music, or were mostly concerned with the technical possibilities of imitating familiar sounds.

Ideas which are relevant to composition with computers were frequently employed in the experimental musical composition of the past thirty years. The work of Joseph Schillinger, for instance, through its systematic analysis and programming, antedates the methods employed by computer composers today. The notion of randomness exemplified in the work of John Cage is also of crucial importance. Randomness (decision avoiding, or more concisely, leaving a decision to chance within an exactly specified range of possibilities) is one of the most important tools of the computer composer.

Computer music falls into two categories: computer composition and computer sound. Specific works may employ one or both of these. Illiac Suite is computer composed but performed by a string quartet. Pieces by James Tenney, Gerald Strang and Peter Zinovieff utilise the computer both as a tool to compose with and a sound-making instrument. The experimental pieces produced at Bell Telephone Laboratories make use of existing tunes like A bicycle built for two but played and sung by a computer.

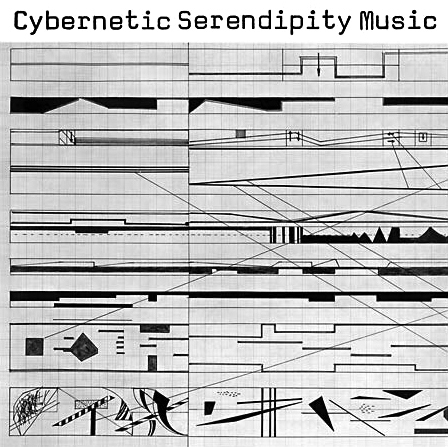

As a souvenir of the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition this record is a selection of work in progress. The cover shows a section of a score for Four Sacred April Rounds 1968 by Peter Zinovieff.

- Liner notes

The ten tracks span over a decade of work, from Lejaren Hiller and Leonard Isaacson’s Illiac Suite (1957) - the first widely recognised computer composition, performed by a string quartet from computer-generated instructions - through John Cage’s Cartridge Music (1960) and Iannis Xenakis’s Stratégie (1962) to pieces composed in 1968 specifically for or around the time of the exhibition. Peter Zinovieff’s January Tensions, at ten and a half minutes the longest track on the record, used the computer both for composition and sound generation. Herbert Brün’s Infraudibles (1967) explored electronically generated sounds at the threshold of audibility.

The LP was reissued as a limited-edition vinyl by The Vinyl Factory in 2014 to coincide with the ICA’s retrospective documentation exhibition.

Audio

Tracklisting:

- A1. Lejaren Hiller & Leonard Isaacson - Illiac Suite (Experiment 4) (4:00)

- A2. John Cage - Cartridge Music (Excerpt) (4:00)

- A3. Iannis Xenakis - Stratégie (Excerpt) (5:00)

- A4. Wilhelm Fucks - Experiment Quatro-Due (5:00)

- A5. J. K. Randall - Mudgett (Excerpt) (7:30)

- B1. Gerald Strang - Composition 3 (2:30)

- B2. Haruki Tsuchiya - Bit Music (Excerpt) (2:30)

- B3. T. H. O’Beirne - Enneadic Selections (4:30)

- B4. Peter Zinovieff - January Tensions (10:30)

- B5. Herbert Brün - Infraudibles (8:30)

Dates of composition:

- A1 - 1957

- A2 - 1960

- A3 - 1962

- A4 - 1963

- A5 - 1965

- B1 - 1966

- B2 - 1968

- B3 - 1968

- B4 - 1968

- B5 - 1967

Gallery