from Pour la forme, Paris 1957, pp. 131-132

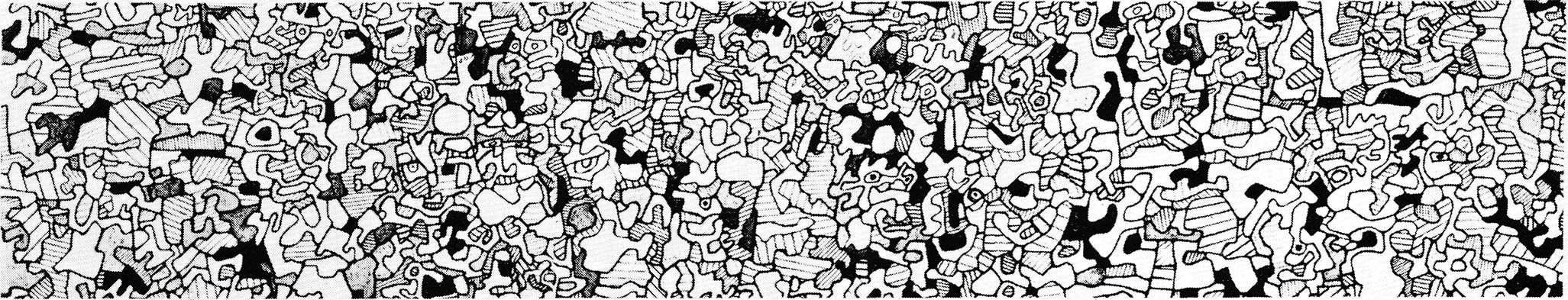

The art of "Cobra" differs from other trends of its time by its starting point, which represents a new perspective of abstract art. We can say that it is an abstract art that does not believe in abstraction. The awareness of this new perspective is expressed in a clear and precise way in the study "Symboler i abstrakt kunst" of the Danish painter Vilhelm Bjerke Petersen, where he demonstrates for the first time, in an original way, the symbolic content of abstractions. Thus the idea of abstraction as a pictorial goal was definitely compromised. Where did Bjerke Petersen hold these ideas? From the old Bauhaus he had passed just before the Nazis destroyed it. From the point of view of arrangement and layout, the book was a new work in the series of "Bauhausbücher" which contained theories of Mondrian, Van Doesburg, Malevich, Klee, Kandinsky, etc. In the content, the obvious result that could be foreseen was a new development from the moment when one would have adopted the new Freudian psychology and the results of the surrealist development in Paris, if the development had not been so abruptly stopped.

The great artistic development in Denmark, starting from Bjerke Petersen’s book in 1933, and until the end of the war, is thus inseparable from the political event that paralyzed cultural life in Germany during the same period. But the new perspective was not established by this book. A long contradictory development had to take place before all the elements necessary for this optics were found. Bjerke Petersen was not even aware of the revolutionary originality of his work. He opposed these ideas two years later by joining Breton’s ideas with a new theory called surrealism. But artists like Richard Mortensen and Ejler Bille, inspired by the first ideas, refused to revise them and excluded Bjerke Petersen from "Linien", the artistic group formed on the new base. This development attracted several new artists in the following years, and a new upheaval was prepared with Egill Jacobsen’s method of spontaneous colorism. Richard Mortensen’s attachment to abstraction made him more and more opposed to this new trend, and in 1939 the break was inevitable. The "Linien" era was over, a new era with several trends or lines began around the magazine "Helhesten", while Richard Mortensen participated in the foundation of the magazine "Aarstiderne", as Bjerke Petersen in 1937 opposed "Linien" with the surrealist magazine "Konkretion".

With the end of the war, the privileged position of Danish artists was over. The adjustment to the international situation created a new crisis. The language that the Dutch movement "de Stijl" had so obviously imposed on the forms of the old Bauhaus was already thoroughly used in its native country, and it is with an immediate understanding of its upheaval that some Dutch artists gathered in the group "Reflex" in 1947 to extract the extreme consequences of the Danish development, in connection with these predispositions. It was a new spark that created new breaks between the Danes, some joining the new development and founding "Cobra", others refusing. The wick had burned until the charge, the explosion linked to the exhibition of "Cobra" in Amsterdam, in 1948.

Personally, I was not directly involved in the preparatory developments in Germany and Denmark. I left my small provincial town in 1936 to go directly to Paris, and begin to be an artist. I knew Kandinsky was there, and I imagined he had a school. But he was not even able to obtain a particular exhibition of his paintings before his death, and so I went to the academy of Fernand Léger, which had the advantage of forcing me to see things in a whole new way, to adapt the French perspective. What eventually left me the opportunity to see all the development was here exposed with some detachment. In any case, that’s what I believe. Others to judge.

The old Bauhaus had shown that a new artistic development could have a technical consequence, which was already the basic thesis of Ruskin and Morris. The old Bauhaus had absorbed the artistic results of the group "Der blaue Reiter" and the group "De Stijl", exploiting them without giving anything back to the artists. It was a feat that was at the same time almost a liquidation. It is significant that the only painter with a revolutionary efficiency, who had been in direct contact with the old Bauhaus, was not a painter, but a photographer who later, in Paris, was to become the painter Wols.

This disastrous development, which reflected much earlier unconscious developments in the relationship between art and technology, made the outline of a definite structure clear, imposing the probability of a similar repetition for the new artistic revolution. But this awareness could at the same time be used to find a method that could avoid this sequence by establishing a correlation between artistic and technical developments simultaneously. This was facilitated by the fact that the back and forth was accelerated in speed, to the point that the reaction was already in preparation simultaneously with the action itself.

This program was already proposed and explained in a study on style and ornament I had published in the architecture journal "Forum" in Holland, in 1947.

The purpose of the activity for an imaginist Bauhaus, here explained, was the establishment of this method-tactic, or if one wishes to express it sincerely, technique. By applying a technique to art, even if the goal is anti-technical, one may arrive at a betrayal, or a negation, of free art. But I see no way to escape this necessity. I do not believe that artistic power will succumb to this change of conditions, but I am convinced that in the event that nothing is done, art will cease to exist, and man with, in the sense that we have here ultimately accepted the word existence, as the expression of a situation.

With the founding of the Reflex Experimental Group in Holland in 1948, a movement was formed for the first time in the history of art on a basis whose importance during the war (especially in Denmark) was revealed primordial: an experimental basis.

H. L. C. Jaffe claims in his book "De Stijl" that the break between Mondrian and Van Doesburg was caused by the involvement of the experimental method in the latter’s system in 1923. He cites in this connection a statement by Van Doesburg, Van Eesteren and Rietveld: "Through our collective work we have examined architecture as a plastic unit of all the arts and this conclusion must lead to a new style. We have examined the laws of space (…) and found that all variations of space can be governed as a balanced unit." But to examine and find is empiricism, and their conclusion on the appearance of a new style is directly anti-experimental. Gropius’s refusal to accept this prophecy, on the contrary, is clearly based on an experimental conception of stylistic development. This does not prevent, however, that Van Doesburg’s spiritual dynamism could have led him to a real experimental conception of stylistics, if Gropius had offered a collaboration on this subject in the old Bauhaus instead of refusing any discussion of this problem. But all developments require time, and the time that has passed since the founding of the "International of Experimental Artists", of "Cobra", has not yet made the opinion more clearly favorable to a discussion on this subject.

At the same time when the group of "Cobra" was striving to reach the experimental stage of art, a group and almost an artistic climate arose in Paris, especially in the literary and cinematographic field, in full development of an experimental semantic under the name of lettrism. It is significant that in our greedy period the most minute false innovations, this upheaval which was done by excluding the word art from the vocabulary, by replacing it with an experimental action, could have passed without one ever considering its importance.

The disorders of the behavior of Saint-Germain-des-Prés were judged as hazardous excesses, without it being realized that such a fermentation can not be completed without something happening.