The first use of the term ‘concrete poetry’ in a manifesto was by Öyvind Fahlström (Sweden) in 1953. He related it more to concrete music than to concrete ‘art’. He emphasised rhythm as ‘the most elementary, directly physically grasping means of effect’ because of its ‘connection with the pulsation of breathing, the blood, ejaculation.’ He opened the way not only for the structural aspects of concrete poetry which play such a prominent part in the theory and practice of Eugen Gomringer (Switzerland), the Brazilians and the Germans, but for expressionist aspects which a second generation of concrete poets has found so potent. bpIMichol (Canada) says that ‘for too many people, concrete poetry is a head trip, which is to say an intellectual trip, and as such I can look at it and admire it. For most people I know it’s a gut experience.’

Fahlström in 1953illustrated what he called a fundamental concrete principle by referring to Pierre Shaeffer’s key discovery in concrete music when he isolated a small fragment of a sound and repeated it with a change of pitch, then returned to the first pitch, and so on. This anticipated one line of development in concrete sound poetry, the electronic-musical one. Fahlström himself did not produce sound poetry until 1961.

The other line, the phonetic one, was anticipated much earlier by such poets as Lewis Carroll (‘twas brillig, 1855), Morgenstern (kroklokwafzi, c. 1890), Sheerbart (kikakoku ! - ekoralaps ! 1897), Khlebnikov, Hugo Ball, Pierre Albert-Birot, Marinetti, Raoul Hausmann, Kurt Schwitters (Ur sonata, 1923-28), Michel Seuphor, Camille Bryen and, within the period covered by this exhibition, Antonin Artaud and Hans Helms.

Sound poetry exists today in a diversity of forms and styles in more than a dozen different countries. Present-day developments had their real beginning in France in the early nineteen-fifties. Concrete sound poetry today is both a return to the primitive and a succession of steps into the technological era. Sten Hanson (Sweden) has described it as ‘a homecoming for poetry, a return to its source close to the spoken word, the rhythm and atmosphere of language and the body, their rites and sorcery.’ Whereas Henri Chopin (France) sees it as finding ‘its sources in the very sources of language and, by the use of electro-magnetics, as owing almost nothing to any aesthetic or historical system of poetry.’ Strangely enough, the invention of the tape-recorder has given the poet back his voice. For, by listening to their voices on the tape-recorder, with its ability to amplify, slow down and speed up voice vibrations, poets have been able to analyse and then immensely improve their vocal resources. Where the tape-recorder leads, the human voice can follow.

However, in 1950, Francois Dufrêne and Gils Wolman (France) began to make their cri-rhythmes and mégapneumes without any aid from the tape-recorder. They had gone back beyond the word, beyond the alphabet to direct vocal outpourings which completely unified form and content. They were back where poetry and music began. In primitive song, the melody often starts on a high note, generally falsetto, and descends. High is high both in volume and in pitch; low is both soft and deep. The emotional outburst, the physical giving out of sound and breath is the song. One thinks of primitive song on hearing FranQois Dufrêne. His cri-rhythmes employ the utmost variety of utterances, extended cries, shrieks, ululations, purrs, yarrs, yaups and duckings, the apparently uncontrollable controlled into a spontaneously shaped performance. Wolman places more emphasis on breath sounds and works in shorter, more isolated, less rhythmically organised soundunits. Both performed at first live, and later recorded their creations on tape, the tape-recorder being used simply as a recording instrument.

However, Dufrêne gradually warmed towards the more creative aspects of the tape-recorder and other electronic devices, which he had at first regarded as contaminations. He began to superimpose one recorded performance over another, and to use certain varieties of echo effect and reverberation. This was mainly from about 1963 onwards, although there are earlier examples. At this time, Jean-Louis Brau also employed similar echo and reverberation techniques in his instrumentations verbales.

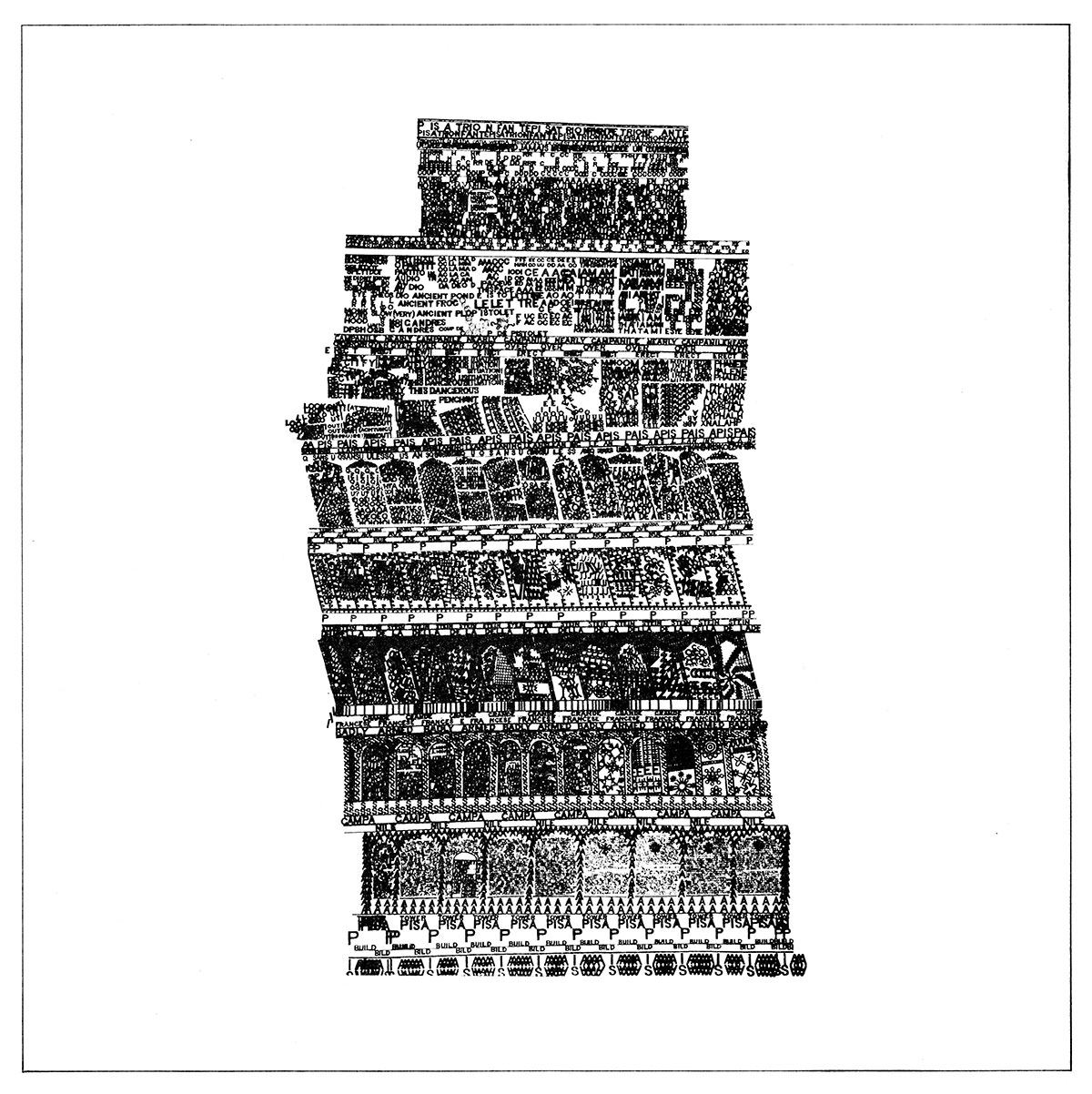

While Brau and Wolman seem to have been less active recently, Dufrêne has continued with a steady output of cri-rhythmes, exhibiting the utmost virtuosity and mastery in an area of sound poetry he has made his own. His performances are highly-skilled physical achievements. Dufrêne was the author also of a lengthy and supreme example of lettriste or ultra-lettriste poetry, published in 1958, ‘Tombeau de Pierre Larousse’, in which he employs words, often proper names, ellided, strangely spelt, given unexpected accents, structured into rhythmical, textured sound patterns of subtlety and force.

With Dufrêne, the time taken to make a tape is the time taken to accomplish a performance (or little more than twice that time if superimposition is used). However a tape can take far longer. Henri Chopin speaks of ‘requiring for each work days and months’ of application and research, as ‘here all the authors are analysts of the language which they synthesize in their productions.’ He is alluding to his own practice and to that of such poets as Paul de Vree, Brion Gysin and Bernard Heidsieck.

Chopin began to work with tape in 1955, though his first really successful composition was not made until 1957. He at first employed the sounds, vowel and consonantal, of words, decomposing and recomposing them in the process. An early work was based upon the words ‘sol air’, recording the individual sounds, slowing them down or speeding them up, superimposing not once but up to fifty times, adding other sounds such as breathing effects and smackings of the lips, also slowed or speeded. In later pieces, Chopin abandonned words altogether and used only particles of vocal sound.

Over the years, he has explored more fully than anyone else these ‘micro-particles’ of the human voice, and has over them the utmost control. The sounds he makes are often almost imperceptible to the ear, but by amplifying, changing speeds and superimposing, one mouth becomes an orchestra. His ‘poésie sonore’, which he utterly distinguishes from ‘poésie phonétique’, is a fully worked out and expressive new language which frees him from the Word, which he regards as an impediment to living, an imposition upon life. His programme thus is both artistic and social-political.

Paul de Vree (Belgium) makes a similar point when he says that ‘all predication is an assault upon the freedom of man. Poetry as I conceive of it, is no longer the handmaiden of princes, prelates, politicians, parties, or even the people. It is at last itself.’

De Vree seems, in his audio-visual poems, at first more orthodox. For a start unlike Chopin’s poèmes sonores and Duf rêne’s cri-rhythmes, they can be written down. But one notices the reliance on sound to convey meaning, the subtle overtones and undertones, fantasies, nonsense words, echoes of the surreal world. De Vree then takes these texts and, in collaboration with a reciter and a composer or an engineer, he realises them in a performance on tape. ‘Actually all depends upon the new possibilities of mechanical expression.’ Using loops and repetitions, echo effects, reverberation and the like, he forges a delicately pointed and precise collaboration between the voice as concrete sound and the form and expressiveness of the original poem. The result is exciting and beautiful. But, he adds, ‘it goes without saying that the reciter (where it is not the poet) and the engineer of sounds have contributed personally to the originality of the realisation. The dawn of the era of electronic poetry is no longer a figment of the imagination.’ De Vree’s first audiovisual poem ‘Veronika’ dates from 1962. It was broadcast in 1963. The function of the machine treatment in many poems by De Vree, Brion Gysin and others is to intensify them and point their qualities, particularly their qualities of sound, to make the poems more like themselves.

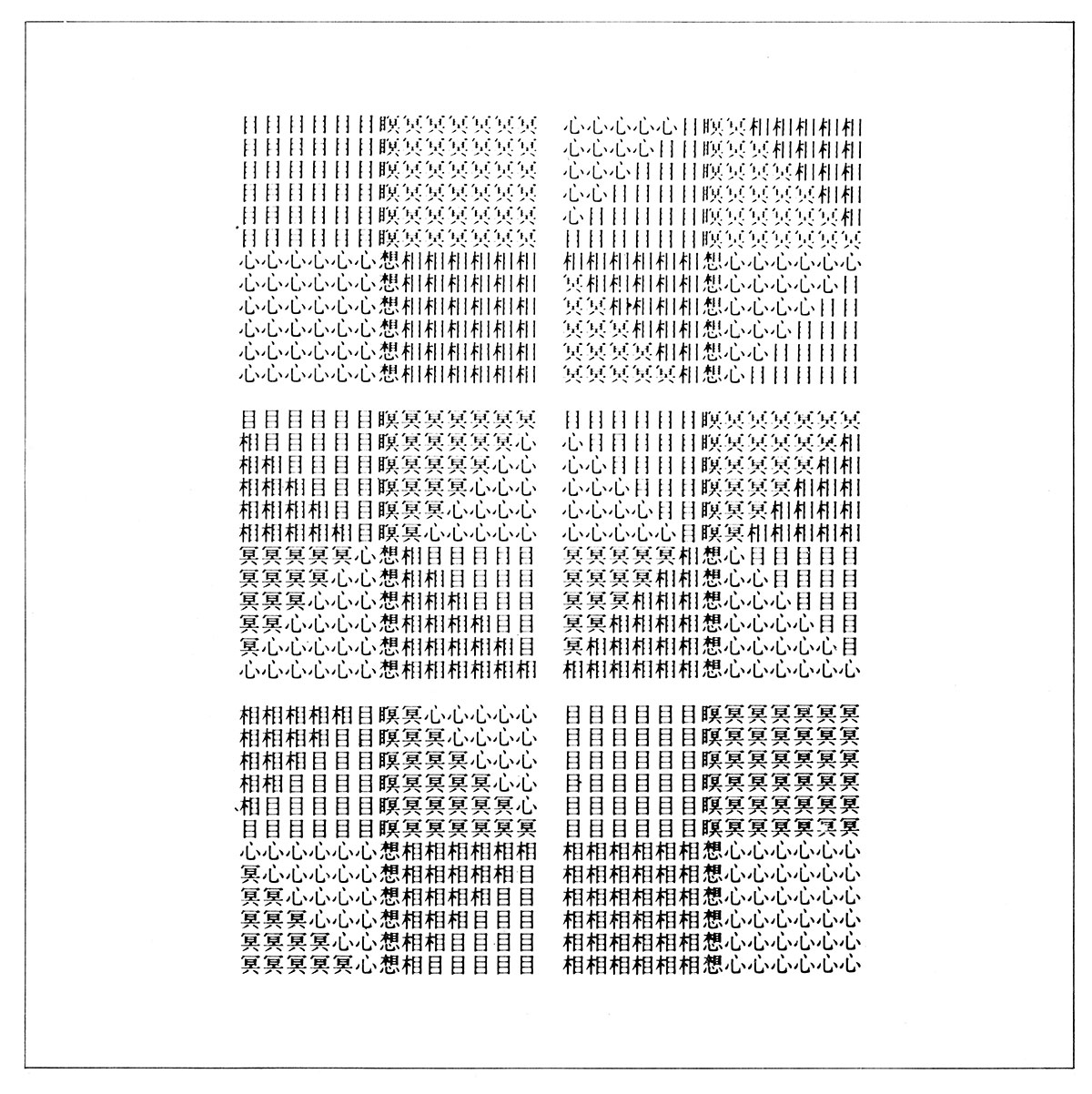

Brion Gysin (Tangiers) is a permutational poet. A simple five-word phrase such as ‘I am that I am’ will produce up to 120 permutations of word order and thus of meaning. ‘Poets are meant to liberate words, not chain them in phrases. Who told poets they were supposed to think ? Poets are meant to sing and to make words sing.’ Gysin restores to words their substance and vitality. By the almost mathematical precision of his permutations he multiplies subtleties of meaning and establishes each word fully in the round. The text may then be further transformed by treatment on tape. ‘I am that I am’, with permutations, superimpositions, speedings and slowings, becomes in turn statement, question, affirmation, doubt, hysteria, negation, obliteration and slow climb back to selfestablishment. Gysin’s poems were first published and broadcast in 1960.

Bernard Heidsieck has been working in France, since 1955, first on a series of poèmes partitions and, since 1966, on his biopsies. He describes both as ‘action poetry’ because they incorporate actuality in the form of recordings of everyday sounds and events, and pre-existing, often topical, texts from newspapers and magazines. The action poem incorporates ‘anything that the poem authorises itself to take’ and, by superimposing various texts or strands of sound, manages to ‘arouse, to awaken other layers of sensibility’, and to deal with aspects of contemporary life in a satirical, humorous or probing way. It is a ‘ritual, ceremonial or event’ whose purpose is ‘to question our daily gestures and words and cries. To appropriate them or dynamite’them. To make them meaningful… to animate our mechanical and technocratic age by recapturing mystery and breath’. Heidsieck’s poetry is made on tape by ‘manipulations of speed, volume, superimposition, cutting and joining.’ Often the texts are rapidly and skilfully read in Heidsieck’s own voice, and the weaving of the strands gives a rich contrapuntal effect which can be appreciated as texture and expressionistic vocal music quite apart from the humour and satire of the disparate textual meanings.

Duf rêne, Wolman, Chopin, De Vree, Gysin and Heidsieck have all been published by Henri Chopin on the records accompanying issues of his magazine Cinquième Saison or, as it is now called, OU. This magazine has been the most important influence in propagating knowledge of concrete sound poetry throughout the world. It is joined now by another series of records published jointly in Sweden by Fylkingen and Sveriges Radio.

The first text-sound compositions in Sweden were by Öyvind Fahlström in 1961 and 1962. In 1964 and 1965, two poetcomposers, Bengt Emil Johnson and Lars-Gunnar Bodin began to work in the field of sound-texts. In 1967, the Fylkingen group concerned with linguistic arts collaborated with the literary section of Sveriges Radio to give several other poets a chance of working in this new area. The Electronic Music Studio of Sveriges Radio was made available to poets and work began in earnest. In 1968, 69 and 70, three festivals of text-sound compositions have been held in Stockholm. Altogether, sixteen Swedish poets and fifteen poets from abroad have been given the opportunity of making compositions for one or more of these festivals. A large proportion of these are included in the records which document the festivals.

Fylkingen, which began as a music organisation, gradually became interested in the other arts, especially from the point of view of the relationship between art and technology. Not only did Swedish sound poets have a fully equipped electronic music studio at their disposal, but several of them had the opportunity also of using computers and voice synthesizers. Calling their works text-sound compositions left them free to use other types of sound, including electronically generated effects. Stereo was common from the first and, since 1967,4-channel reproduction has almost become the rule, allowing sound to be placed, controlled and moved in space with the utmost precision.

Bengt Emil Johnson has been foremost in the search for new techniques of expression. In ‘Through the mirror of thirst’, fragments of one of his earlier poems have been randomly selected and, also on a chance basis, have been allocated to one of four voices; controlled as to density per time unit of 30 seconds; in speed, from very fast to very slow; spatial position on the four channels; type of electronic treatment, etc. In this way, within a basically semantic structure, small details of recorded text have been separated out and vividly exposed.

In another piece, Johnson uses a computer to effect a series of gradual transformations from one text to another; and for a third, produced also with the aid of a computer, a text of invented words which obey all the rules of Swedish wordconstruction and syntax was prepared. Lars-Gunnar Bodin has a musician’s attitude to his material. In ‘From any point to any other point’ the text has been modified and transformed electronically until the semantic meaning disappears and only the rhythmic structure of language remains. All that is left is a vestige of ‘oral behaviour’. This approach is appropriate in a work which discusses and reflects on scientific and technological views of the world.

The trend is taken still further by Christer Hennix Lille, also a composer, who in his ‘Still Life, CL’ makes one of the first uses of synthetic speech in an artistic creation. The synthesizer’s computer unit is used to ‘generate parameters of articulation, so that malformations in syntax and pronunciation become a ‘value’ of the ‘local’ mutation frequency of the piece’. Q is a ‘code’ which has reference to the behaviour of memory in language as related to the genetic code of the individual. In the future, many more works are likely to be realised with the aid of the synthesizer.

In theory, it will be possible to produce synthetically exactly the voice quality required as constituent material for any composition.

Sten Hanson makes use of the letters A C G and T, which are abbreviations for the names of the bases forming the genetic code, in his piece ‘La destruction de votre code génétique par drogues, toxines et irradiation.’ As the piece proceeds, the pronunciation of the letters is distorted and broken down by the introduction of ‘foreign’ sound elements produced in a purely electronic way. Hanson, in his smallscale works, uses advanced techniques for social-political ends.

Åke Hodell, after a number of very effective phonetic pieces, has produced large-scale works almost in the documentary mould. ‘USS Pacific Ocean’ is concerned with a dramatic, imagined political crisis; while ‘Where is Eldridge Cleaver ?’ is based on contemporary events in America. In this piece, 4-channel tape-recording is used effectively to give, for example, the sound of soldiers marching round and round the audience.

There is a danger, of course, that electronic and other effects will be used in a sterile way, but the Swedes, on the whole, seem to have avoided this. Johnson and Bodin, largely in musical terms, and Hanson and Hodell in social-political terms, have proved their ability to use effects to engage and implicate the listener. Often, there is a continous interplay between semantically meaningful portions and the resonant development of these, frequently in combination with other sounds. Form is a vehicle for content, and even the use of 4-channel reproduction is carried out in a way that illuminates the meaning of the composition.

There seem to be as many approaches as there are poets. Many others could be mentioned:

Ernst Jandl (Austria), the primary exponent, at the present time, of phonetic poetry for the unaided voice, who breaks words up into meaningful soundfragments, recomposes them, organises them with rhythmic and structural precision. (Even Jandl, though, has realised electronically some of his poems in collaboration with the British Broadcasting Corporation’s Radiophonic Workshop);

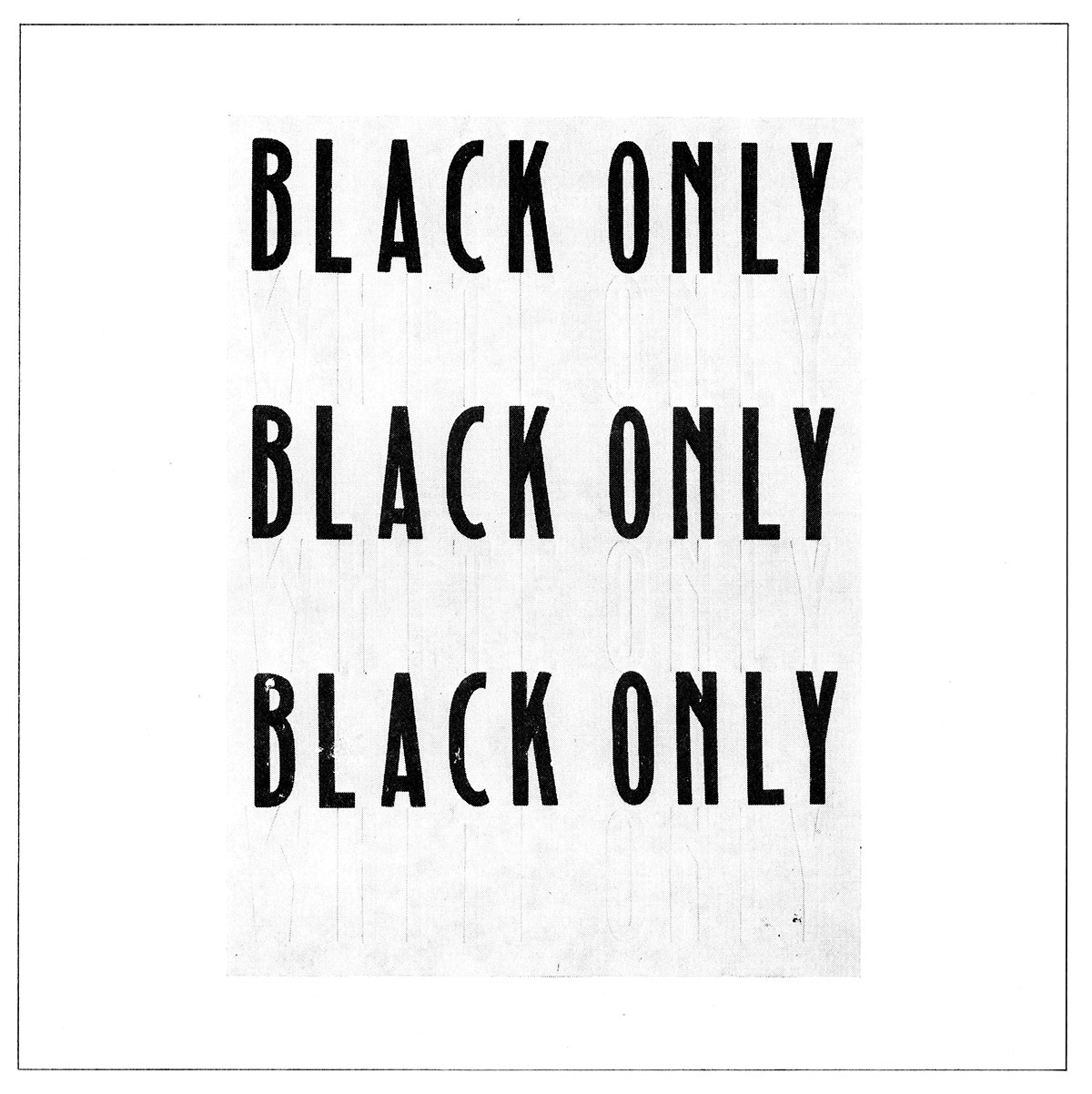

Ladislav Novak (Czechoslovakia), whose complex superimpositions of, often, a single sentence in Czech or Latin seem to be cries of freedom, in line with Franz Mon’s observation that spatially articulated language becomes effective at the point when ‘conventional language sanctioned by society reaches its limits, or for some reason may not be used’;

Frans Mon himself (West Germany), who has conducted a continuing study into the structure and method of language;

Gust Gils (Belgium) who uses vocal sounds without semantic meaning, seeing the sound poem as an opportunity for a poet whose native language has a limited audience to break out of his isolation;

Bengt af Klintberg (Sweden) whose work often contains elements of folklore, cusha-calls and incantation;

Svante Bodin (also Sweden) who has used the computer to scramble and transform a text in a number of valid ways;

and dozens more, in Sweden, Denmark, Finland, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Czechoslovakia, U K, U S A, Canada, Japan, South America and elsewhere.

Two lines of development in concrete sound poetry seem to be complementary. One, the attempt to come to terms with scientific and technological development in order to enable man to continue to be at home in his world, the humanisation of the machine, the marrying of human warmth to the coldness of much electronically generated sound. The other, the return to the primitive, to incantation and ritual, to the coming together again of music and poetry, the amalgamation with movement and dance, the growth of the voice to its full physical powers again as part of the body, the body as language.

The very diversity of sound poetry is in line with its emphasis on the freedom of the individual and the withering of external authority, on man as a communal and social animal, on communication as a lifegiving activity, things which in this bureaucratic and technocratic age we need constantly to remember.