|

|

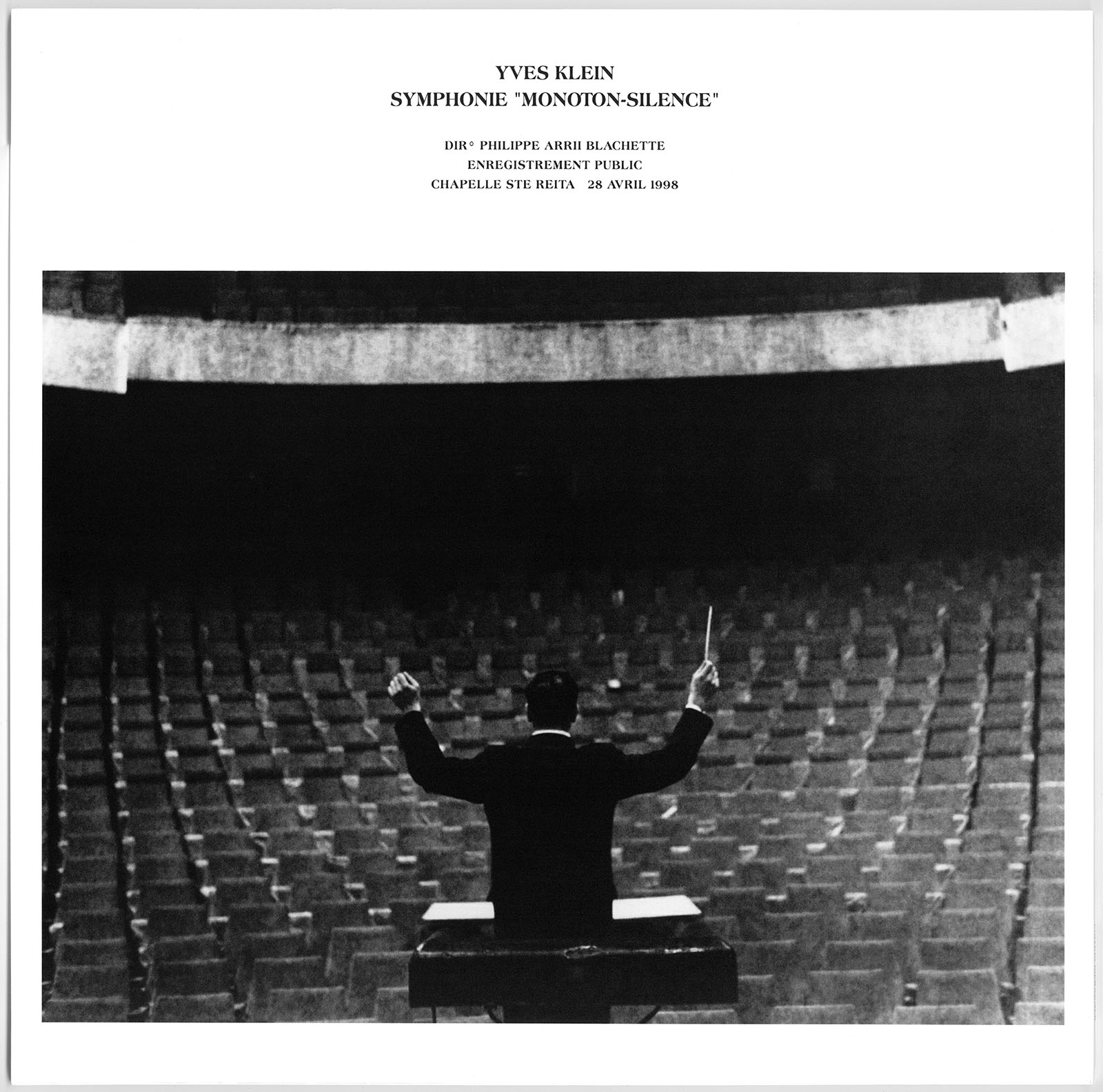

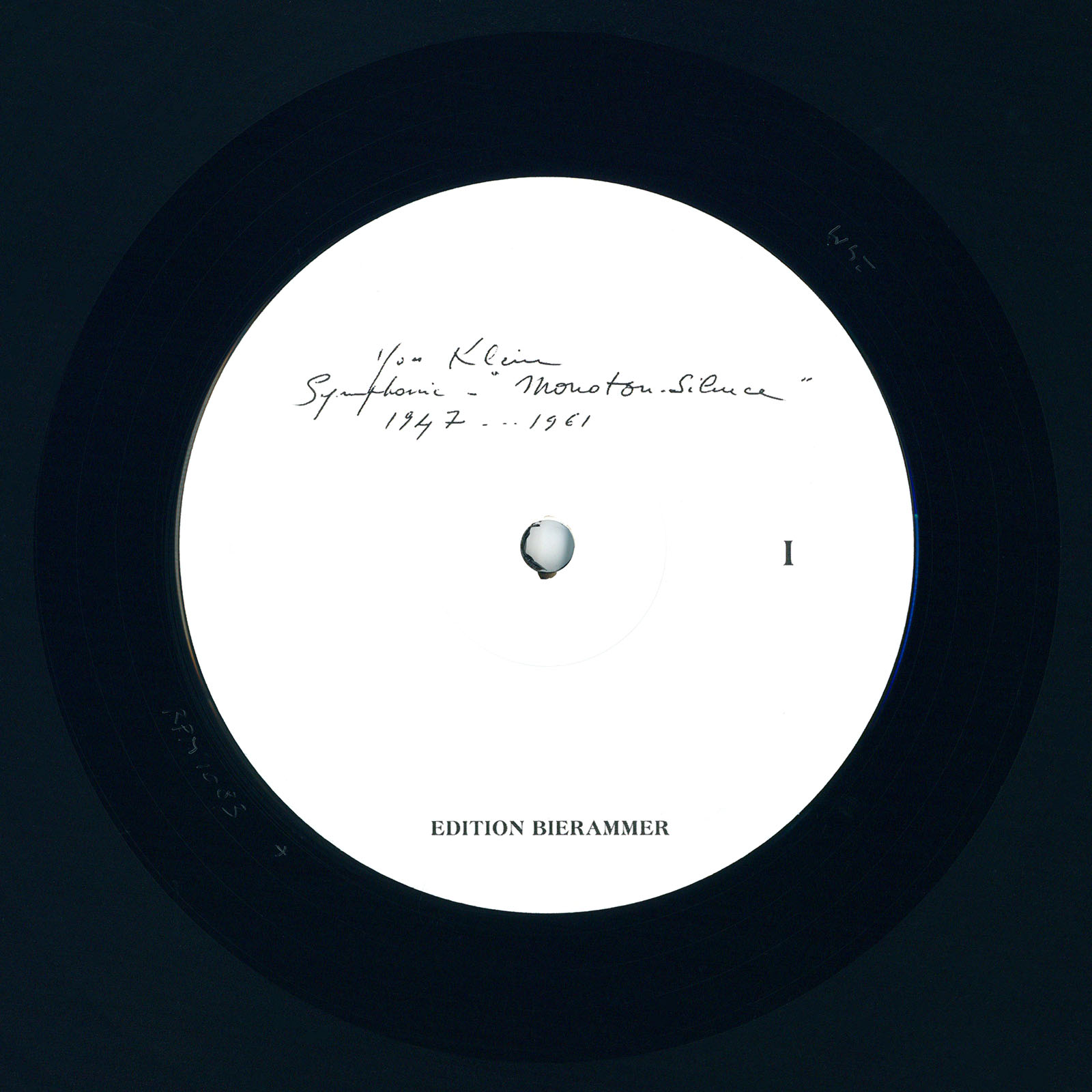

| Symphonie 'Monoton-Silence' | |

| Authors | Yves Klein |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Edition Bierammer |

| Publishing date | 2024 (first recording, 1961) |

| Edition | 250 copies |

| Format | LP, Limited Edition |

The Symphonie ‘Monoton-Silence’ is a conceptual musical work by French artist Yves Klein (1928–1962). Scored for twenty singers, ten violins, ten cellos, three double basses, three trumpets, three flutes, and three oboes, the piece unfolds in two equal movements: twenty minutes of a sustained D major chord performed at full volume, followed by twenty minutes of unbroken silence. Klein conceived it as the central statement of his entire artistic practice - a sonic equivalent of his monochrome paintings and an attempt to transpose colour’s stillness into sound.

Origins and Conception

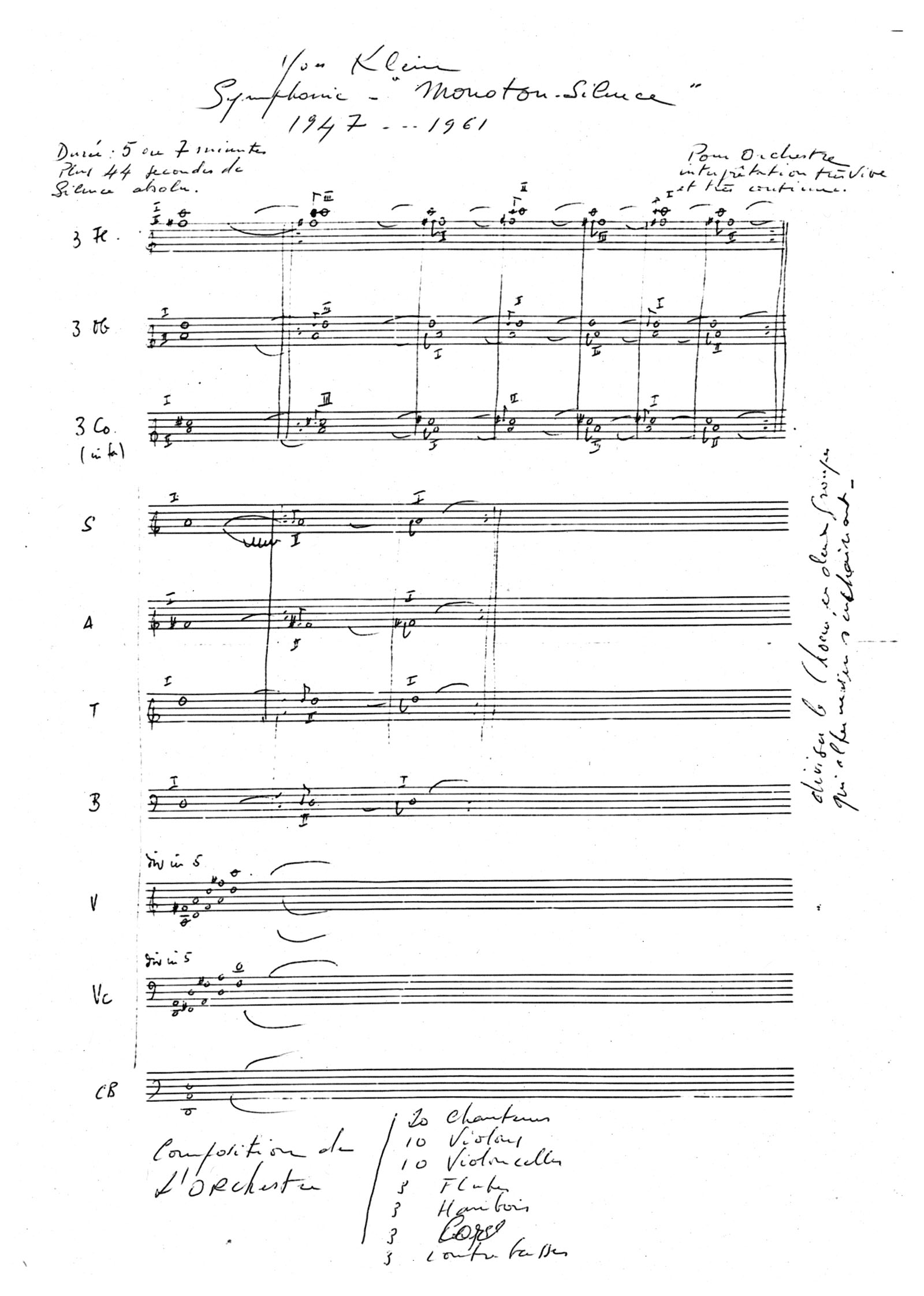

Klein’s own accounts of when he conceived the symphony are characteristically contradictory: the score is dated 1947, while his interviews and written texts give 1949 as the year of its conception. He was nineteen or twenty years old at the time - a young man from Nice with no formal musical training, working in a post-war French art world still absorbing the shock of Schoenbergian serialism.

The composer Éliane Radigue, who was then married to Arman and was one of Klein’s close friends, later described the work’s origins in a telling anecdote. On a beach in Nice in 1954, shortly after Klein had first encountered the Lettrists, a group of friends fell into improvising in glossolalia - non-semantic sounds and syllables - through the night. The improvisation gradually converged into a continuous, sustained tone. Radigue, the only musician present, tuned the voices into a single chord. Klein recognised in that moment the germ of a work he had been nursing for years.1

When Klein eventually sought help realising the symphony, he first turned to Radigue herself, asking her to write and produce it. She declined, citing reasons she described only as “numerous,” and redirected him to the composer Louis Saguer. Through Saguer - and, by extension, Radigue’s connections at the Club d’Essai de la Radiodiffusion-Télévision française, where she had worked alongside Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry on musique concrète - Klein finally found a musical collaborator. In 1959, Saguer and Klein worked through a range of harmonic possibilities, from the most complex atonal combinations to the simplest tonal chords. Klein settled on the most elementary option: a bare D major triad.2

During this period of concentration, I created, around 1947–1948, a monotone symphony whose theme expresses what I wished my life to be. This symphony of forty minutes duration (although that is of no importance, as one will see) consisted of one unique continuous sound, drawn out and deprived of its beginning and of its end, creating a feeling of vertigo and of aspiration outside of time. Thus even in its presence, this symphony does not exist. It exists outside of the phenomenology of time because it is neither born nor will it die, after existence.

- Yves Klein, Overcoming the Problematics of Art, 1959

The 1960 Premiere

The public premiere of the Symphonie Monoton-Silence took place on the evening of 9 March 1960, in the grand salon of the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain, directed by Maurice d’Arquian, in Paris. Roughly one hundred invited guests attended. Alain Bancquart - a student of Louis Saguer - conducted an ensemble of six string players and three singers, a reduced realisation calibrated to the gallery’s acoustics.3

The performance was inseparable from an accompanying action that would become one of the most reproduced images in post-war art history. Three nude models entered the space, applied International Klein Blue pigment to their bodies using sponges, and pressed themselves against large sheets of white paper laid on the stage and walls, creating what Klein called Anthropométries - body imprints made while the symphony sounded. The musicians and the models worked in the same room, the sustained chord filling the space as the blue traces accumulated on the paper. Klein directed the entire proceedings from a distance, dressed in a dinner jacket.

One of the singers who performed in the original 1960 event, Sahra Motalebi, later described the sound of the chord: “The reality is that it’s like a kind of bizarre primordial universe chorus. It’s not like a note you’ve ever heard.”4

The symphony was performed again on 17 July 1961, when an ensemble conducted by Philippe Arrii-Blachette played the work on location for the filming of a session of Anthropométries, footage later incorporated into Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi’s documentary Mondo Cane (1962), which competed at Cannes that year.5

Musical Structure and Score

The score specifies an ensemble divided into three sections: strings (ten violins, ten cellos, three double basses), brass (three horns), and woodwinds (eight flutes and eight oboes), joined by a chorus of twenty singers divided into two alternating groups. In practice, Klein’s instructions allowed for flexible realisation depending on the acoustic properties of the performance space - the 1960 premiere was given by a fraction of the notated forces.6

The duration, too, was treated as variable. While the canonical version runs to twenty minutes of sound and twenty of silence, Klein sanctioned shorter realisations: a division of five to seven minutes of sustained tone followed by an equal silence was performed at the Festival Manca in Nice in 2005, in a version conducted by Philippe Arrii-Blachette. A ten-minute version - five minutes of chord, five of silence - was used in rehearsal by conductor Petr Kotik for later performances.7

What the score does not permit is any development, variation, or resolution. The chord begins, sustains at full volume, and ends. The silence that follows is equally active: performers remain in their playing positions, instruments at the ready, for the duration of the second movement. Klein insisted that the silence was not an absence but the true content of the work.

Silence … This is really my symphony and not the sounds during its performance. This silence is so marvelous because it grants happenstance and even sometimes the possibility of true happiness, if only for only a moment, for a moment whose duration is immeasurable.

- Yves Klein, Truth Becomes Reality, 1960

Historical Context and Significance

The work was conceived at a moment when the central problem in new European music was what to do after Schoenberg - how to continue after the dissolution of tonal harmony. Klein, entirely outside this debate, arrived at a solution that bypassed its premises altogether: a single, stable, unresolved chord lasting as long as it lasted, followed by the performance of nothing.8

The musicologist Valerian Maly observed that in 1947, when Klein was sketching his symphony, the question of Schoenbergian technique was still “heatedly debated and wrestled with in new music circles,” while the young artist from Nice was working in the opposite direction - “a symphony that refrains from all development.”9 Klein’s reduction to a single consonant sound anticipated the effects of his monochrome paintings, and the concept of the symphony as a whole pointed toward his broader ambition: the dematerialisation of the art object.

The work has frequently been compared to John Cage’s 4′33″ (1952), which similarly presents silence as performed content. The relationship is both chronological and conceptual. Klein’s score predates Cage’s piece by several years, though the Symphonie Monoton-Silence was not publicly performed until 1960 - eight years after Cage’s premiere in Woodstock. Academic research into the work’s development has traced the renaming of the symphony from Symphonie Monoton to Symphonie Monoton-Silence as a delayed reception of Cage’s ideas: the “silence-after” acknowledged as a distinct, composed element rather than simply the cessation of sound.10

Klein also explored early electronic sound in collaboration with Pierre Henry - a relationship facilitated by Éliane Radigue - and maintained a correspondence with Karlheinz Stockhausen about the relationship between sound and space. These exchanges inflected the symphony’s conception without altering its final, radical simplicity.

Performances

The Symphonie Monoton-Silence has been performed rarely since Klein’s death from a third heart attack in June 1962, at the age of thirty-four. The New York performance, mounted some decades after the premiere, appears to have been the work’s American debut; it was reviewed by a New York Times critic who described the chord’s evolution across twenty minutes as initially “gentle” and “fragile” before becoming “strangely electronic” and almost inhuman, ending “as abruptly as it had begun.” He described the silence that followed as “as absolute (and enjoyable) as any I’ve ever experienced in a crowded place in New York City.”11

On 12 January 2017, the work was performed at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco before an audience of more than one thousand people, conducted by Petr Kotik - himself a composer and minimalist who had long championed music by artists whose primary medium was not composition. The programme included Marcel Duchamp alongside Klein.12

A performance at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. brought the total number of documented performances to roughly ten - figures that underscore the work’s rarity as a live event.

Releases and Recordings

Despite the symphony’s importance in the history of conceptual and minimalist art, no commercial recording existed for more than six decades after the premiere. A recording made by Philippe Arrii-Blachette in April 1998 at the Chapelle Sainte-Rita in Paris - a performance in which Klein’s estate was involved - remained unreleased for more than twenty-five years.

Edition Bierammer LP (2024)

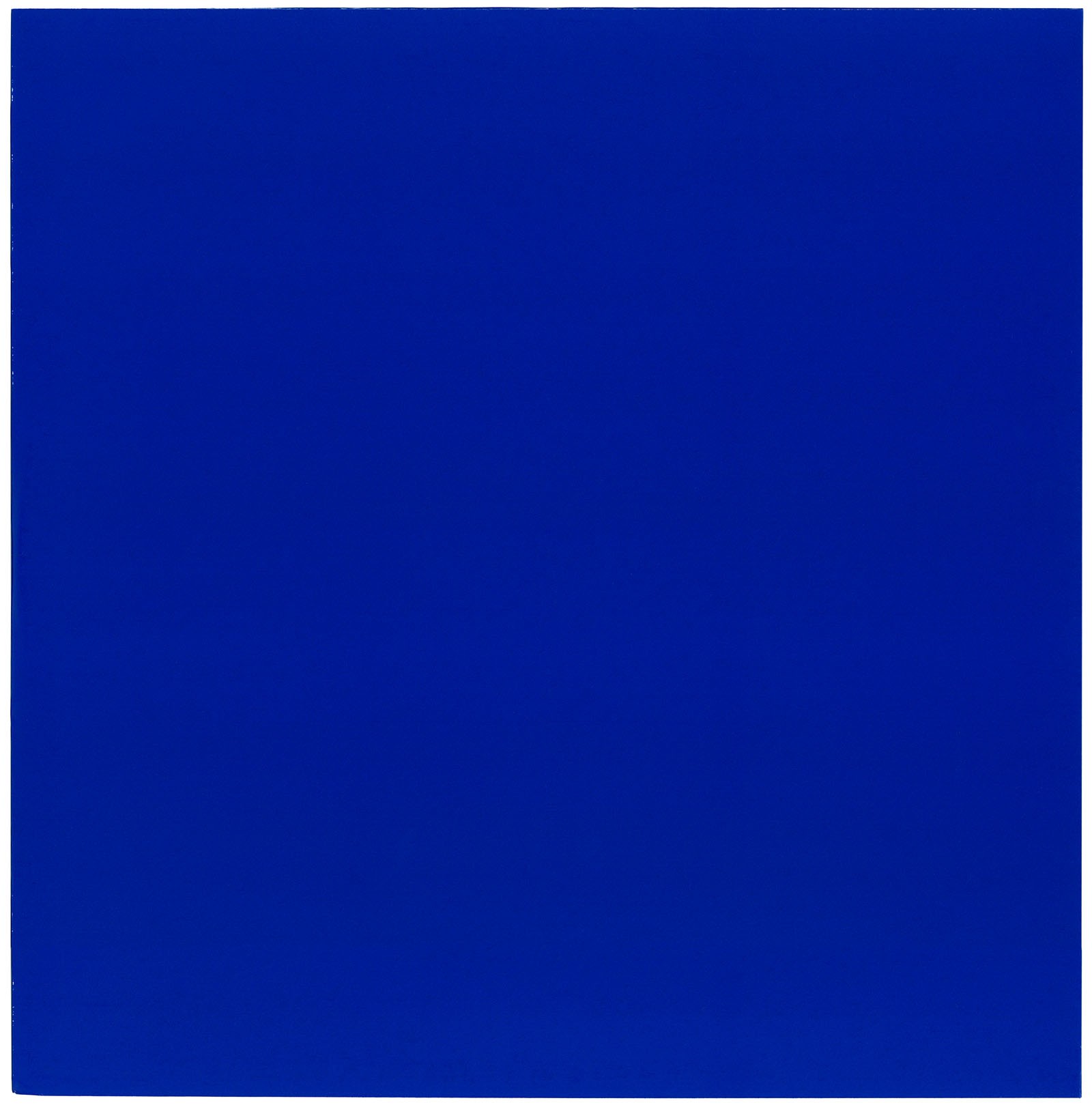

In 2024, the Austrian label Edition Bierammer issued the first-ever commercial release of the Symphonie Monoton-Silence on vinyl LP. The recording captures the 1998 Chapelle Sainte-Rita performance, conducted by Philippe Arrii-Blachette. The release is limited to 250 copies, pressed with an International Klein Blue inner sleeve and an A4 insert reproducing Klein’s original score - an object whose design deliberately extends the work’s visual logic into the packaging itself.13

Edition Bierammer had previously released recordings by Joseph Beuys, Roman Opalka, Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik, and Jean Tinguely - artists whose sound works occupy the same territory between fine art and radical sonority that the label has made its focus. The Klein release was described by distributors as among the most historically significant artist records issued in recent years. It sold out at the label and achieved secondary-market prices well above its original issue price.

The release appears on Discogs catalogued as a limited edition LP with no catalogue number, released in Austria in 2024, classified under the genres Non-Music and Classical, with the styles Contemporary and Sound Art.14

Audio

Gallery

-

Éliane Radigue, quoted in the Wikipedia article on the Monotone-Silence Symphony; and in Frédéric Prot, Embrasure, Editions 5 Continents, Milan, 2012. ↩

-

Frédéric Prot, Embrasure, Editions 5 Continents, Milan, 2012; excerpted at the Yves Klein official archive. ↩

-

Ibid. The performance date and venue are documented in the Yves Klein archive. ↩

-

Sahra Motalebi, quoted in the Soundohm product description for the Edition Bierammer LP (2024). ↩

-

Frédéric Prot, Embrasure, excerpted at the Yves Klein official archive. ↩

-

Yves Klein archive, La Symphonie Monoton-Silence. ↩

-

Symphonie Monoton-Silence, Wikipédia (French); Wenger Corporation, “Yves Klein – Monotone-Silence Symphony”. ↩

-

Valerian Maly, liner notes for the Edition Bierammer LP, quoted at Penultimate Press. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Théodora Psychoyou, “Le ‘silence-après’ d’Yves Klein (1958–1961)”, Marges, no. 19, 2016. ↩

-

New York Times critic quoted in the Wenger Corporation article on the symphony’s acoustical properties. ↩

-

Johanna Keller, “Blue Monotone,” The Hudson Review, October 2019. ↩

-

Penultimate Press product listing; Rumpsti Pumsti product listing. ↩

-

Discogs release page, Edition Bierammer, Austria, 2024. ↩