Mémoires is an artist’s book by Guy Debord with structures portantes by Asger Jorn, published by the Internationale Situationniste and printed by Permild & Rosengreen in Copenhagen in 1959. The second of two collaborative books by Debord and Jorn - following Fin de Copenhague in 1957 - Mémoires is constructed entirely from détourned material: fragments of text, maps, photographs, cartoons, and advertisements clipped from newspapers, magazines, and books, overlaid with Jorn’s coloured ink marks. Its colophon declares “Cet ouvrage est entièrement composé d’éléments préfabriqués” (This work is entirely composed of prefabricated elements). The book covers the years 1952–53, a period during which Debord, then in his early twenties, broke with the Lettrist movement, founded the Lettrist International, and screened his first film, Hurlements en faveur de Sade. Often described as one of the most significant artist’s books of the twentieth century,Situationniste Blog, “Memoires by Debord & Jorn [1959] – with a unique cover”. Accessed 2025-02-13. it was printed in a small edition and circulated privately, never offered for public sale during Debord’s lifetime.

Background

Asger Jorn and Guy Debord first met in Paris in 1954, after Jorn received copies of Potlatch, the bulletin of the Lettrist International.Christian Nolle, “Books of Warfare: The Collaboration between Guy Debord & Asger Jorn from 1957-1959”, 2002. The encounter began an intense working relationship. In June 1957, Jorn’s Mouvement International pour un Bauhaus Imaginiste merged with the Lettrist International and the London Psychogeographical Association to form the Situationist International (SI) at Cosio d’Arroscia in Italy. Jorn and Debord had already produced their first book together that May: Fin de Copenhague, credited to Jorn with Debord as “conseiller technique pour le détournement” (technical adviser in détournement), published by Jorn’s Bauhaus Imaginiste in an edition of 200 copies. That book had been assembled in a single drunken afternoon: after raiding a Copenhagen newsstand for magazines and newspapers, the pair produced 32 collage pages overnight, which were transferred to lithographic plates at the workshop of V. O. Permild.Andrew Hussey, The Game of War: The Life and Death of Guy Debord (London: Jonathan Cape, 2001), p. 109. Jorn then climbed a ladder above the fragile zinc plates and dropped cups of coloured Indian ink onto them from above, a deliberate affront to the conventions of printmaking.

Mémoires followed a different process. Debord composed the collage material alone, working methodically over the winter of 1957–58, gathering and arranging fragments from newspapers, books, and magazines, all of which predated 1957.In Debord’s annotated copy, he noted: “All the books and newspapers used here were published at the latest in 1957, and generally before.” Quoted in auction catalogues; see also Boris Donné, (Pour Mémoires) (Paris: Allia, 2004). In an annotated copy that later entered the archives of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Debord identified the sources of his détournements, which Boris Donné traced and catalogued in his 2004 study (Pour Mémoires). Donné’s research revealed the breadth of Debord’s reading at age twenty-two - Shakespeare, Pascal, Bossuet, Baudelaire, and many others - and demonstrated that the seemingly random fragments formed a carefully structured autobiographical narrative.Boris Donné, (Pour Mémoires): un essai d’élucidation des Mémoires de Guy Debord (Paris: Allia, 2004), 157 pp.

Where Fin de Copenhague had been spontaneous, Mémoires was composed. As the historian Howard Slater observed of the difference between the two collaborators, the Scandinavian Situationists tended to produce their theories after the event, while the French wanted everything worked out beforehand.Howard Slater, “Divided We Stand: An Outline of Scandinavian Situationism,” Break/Flow, 2001. Jorn, credited with the structures portantes (load-bearing structures), applied his coloured inks to the zinc plates using a match dipped in Indian ink, creating marks that sometimes connected sentences across the page and sometimes obscured them.Nolle, “Books of Warfare.” His role was more constrained than it had been in Fin de Copenhague, where he had worked freely with streams of colour; here, Debord’s compositional structure governed the overall layout.

The pages were printed by Permild & Rosengreen in Copenhagen in December 1958, using iris printing - a technique in which colours blend together softly across the print surface.V. O. Permild, in Troels Andersen and Aksel Evin Olesen, eds., Erindringer om Asger Jorn (Silkeborg: Galerie Moderne, 1982). Despite the printed date of 1959, Debord himself confirmed the book was produced in the autumn of 1958. It was published by the Internationale Situationniste and distributed privately among associates, never sold commercially. The exact edition size is uncertain: sources variously cite figures from 200 to 500 copies.AbeBooks lists an original described as “number 53 out of 200” while the Situationniste Blog states “500 copies of Memoires were originally issued.” The British Library’s copy note refers to “perhaps one thousand in small circulation amongst associates.”

Contents

The book contains 64 unpaginated pages divided into three sections, each introduced by a date and an epigraph. The first section, June 1952, opens with a passage from Karl Marx: “Let the dead bury the dead, and mourn them… our fate will be to become the first living people to enter the new life.” The second, December 1952, carries a long quotation from Johan Huizinga’s The Waning of the Middle Ages, describing the pervasive melancholy of the fifteenth century: a world convinced it was approaching its end, where the aristocracy declared they had known only misery. The third section, September 1953, quotes from a letter by the Prince de Soubise to the Duc de Choiseul, written after a military defeat.

These three dates correspond to formative episodes in Debord’s life. In June 1952, he attended the Cannes Film Festival, where members of the Lettrist movement staged a disruption, and shortly afterwards participated in the split from Isidore Isou’s Lettrist group that led to the founding of the Lettrist International. In late 1952, he premiered Hurlements en faveur de Sade, a film consisting entirely of alternating white screens with spoken dialogue and long stretches of black silence, which provoked audience fury.Guy Atkins, Asger Jorn: The Crucial Years 1954–1964 (London: Lund Humphries, 1977), p. 63. By September 1953, the Lettrist International was an established if marginal presence in Left Bank Paris, issuing manifestos, conducting dérives through the city, and developing the concepts of psychogeography and détournement that would carry over into the SI.

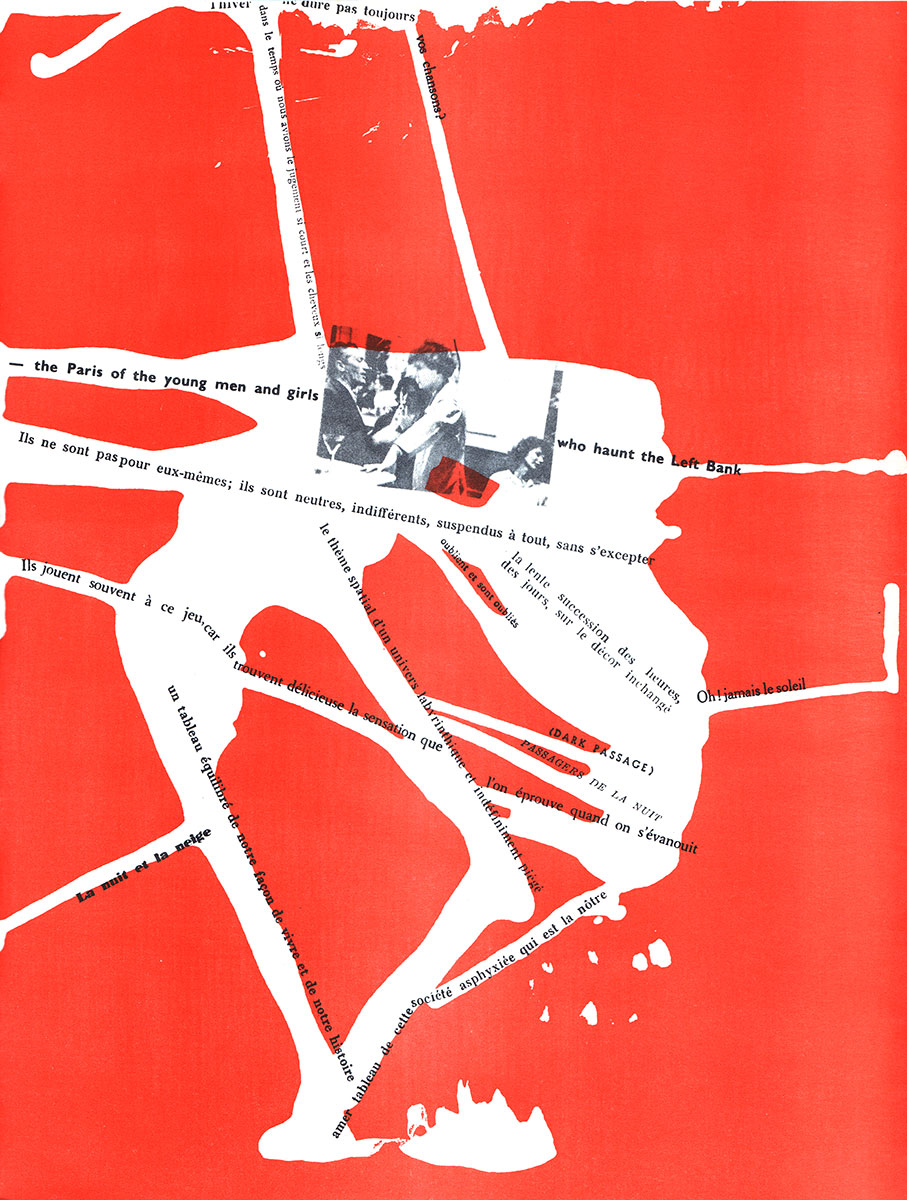

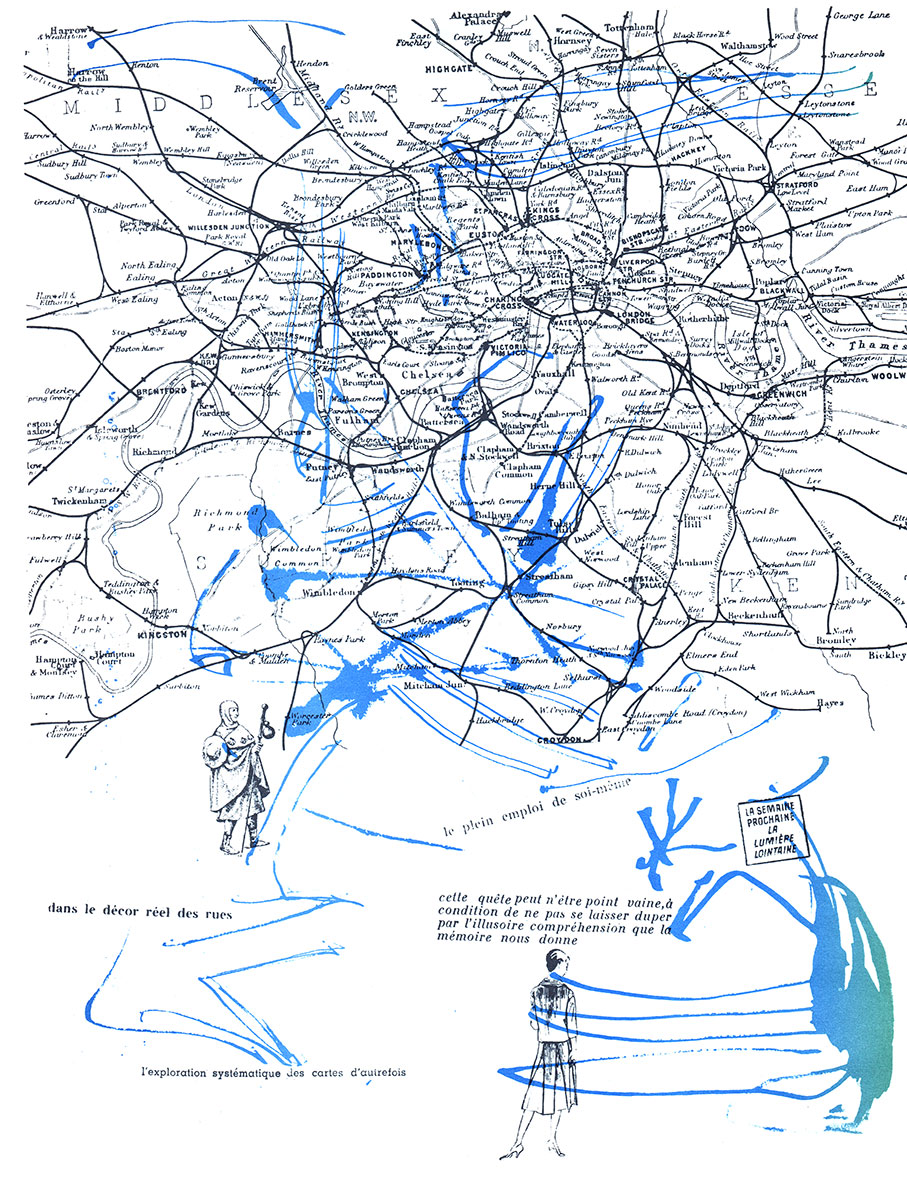

Rather than written passages, the book is constructed through détourned or repurposed found materials, such as newspaper clippings, photographs, cartoons, and advertisements, as well as quotations from figures who included Marx and Huizinga, as well as the popular press. Eschewing a strict vertical and horizontal orientation, the book instead proposes an all-over viewing, as if navigating a map, yet with no direction given.

The work operates in two layers. The first, printed in black ink, reproduces the found text and graphic elements: fragments of maps of Paris and London, illustrations of siege warfare, reproductions of old master paintings, advertising slogans, and questions clipped from interviews and magazines. The second layer consists of Jorn’s coloured inks - splashes, skeins, lines, and blots applied across the pages in vivid hues that shift between sections. These marks sometimes forge visual connections between unrelated text fragments, sometimes cover them, and sometimes float independently. Greil Marcus, writing about the book, noted that it possesses a distinctive voice across its pages, one of adventure and reflection, suggesting that no matter how empty the world may seem, anything remains possible.Greil Marcus, “Guy Debord’s Mémoires: A Situationist Primer,” in Elisabeth Sussman, ed., On the Passage of a Few People through a Rather Brief Moment in Time: The Situationist International 1957–1972 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989).

The final page carries an orange swirl above a single sentence: “Je voulais parler la belle langue de mon siècle” - “I wanted to speak the beautiful language of my century.”

The Sandpaper Cover

The book’s most notorious feature is its cover: a dust jacket made from heavy-grade sandpaper (Viks Nr. 2), wrapped around the white card wrappers but not permanently affixed, so that it could be detached for reading. The idea originated from a conversation between Jorn and the printer V. O. Permild. Jorn had long asked Permild for an unconventional cover material - he suggested sticky asphalt or glass wool, and joked that it should be possible to tell from looking at someone’s hands whether they had held the book.

He acquiesced by my final suggestion: sandpaper (flint) nr. 2: ‘Fine. Can you imagine the result when the book lies on a blank polished mahogany table, or when it’s inserted or taken out of the bookshelf. It planes shavings off the neighbour’s desert goat.’

- V. O. Permild, Erindringer om Asger Jorn, 1982

As Permild put it, Jorn loved to place “small time-controlled bombs.” The sandpaper jacket turned the book into an object that could damage anything it touched - other books on a shelf, a polished table, the reader’s own hands. It inverted the typical relationship between a book and its surroundings: instead of being a precious object to be protected, Mémoires threatened to destroy whatever sat beside it. In practice, most owners learned to handle it carefully or to store it separately, which perhaps only confirmed the Situationist observation that every attempt to destroy the commodity form tends to produce a new kind of precious object.

Three artist proofs are known to exist, each differing from the main edition in their use of 3M sandpaper rather than the Danish Viks Nr. 2.Wikipedia, “Mémoires”. Accessed 2025-02-13. One is inscribed to “Mr. Ulmann” (probably Jacques Ulmann), dated April 1959 and signed by Jorn. A second was dedicated by Debord to Ghislain de Marbaix. The third, undedicated, was formerly held at the Bibliothèque Claude Bernard. All three are now in private collections.

Editions

The original 1959 edition, printed on thin semi-transparent paper of approximately 80 grams, was distributed only in private circles. It was not until 1993 that Debord authorized a reprint, published by Jean-Jacques Pauvert at Belles Lettres in a run of 2,300 copies.Wikipedia, “Mémoires.” This facsimile included a brief introduction by Debord but omitted the sandpaper cover, and was printed on thicker white stock. The colour reproduction differed noticeably from the original - Jorn’s subtle gradient transitions between pages were flattened, and two pages that had carried only a faint wash of green in the original appeared in the reprint with splashes of red ink. The facsimile also introduced a cropped black-and-white portrait of Debord where the original had a plain black page, lending the reprint a commemorative character absent from the first edition.Nolle, “Books of Warfare.” Nolle’s detailed comparison of the 1959 and 1993 editions documents the colour discrepancies, the changed typeface on chapter pages, and the addition of Debord’s portrait. A significant number of the Pauvert copies were later destroyed in a fire at the Belles Lettres storage facility.Wikipedia, “Mémoires.”

In 2004, Éditions Allia published a new edition that included, alongside a facsimile of the original pages, reproductions of nine of Debord’s original collage layouts, nine pages from Debord’s annotated copy showing the sources of each détournement, and the complete list of identified sources.Éditions Allia catalogue entry. ISBN 2-84485-143-6. The same publisher simultaneously issued Boris Donné’s (Pour Mémoires): un essai d’élucidation des Mémoires de Guy Debord, a 157-page study that traced the origin of nearly all the book’s appropriated fragments and reconstructed the autobiographical narrative they encode.

Copies of the original 1959 edition are held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, the British Library, and other institutional collections. The book has been the subject of extensive scholarly attention, including Ella Mudie’s 2016 study “An Atlas of Allusions: The Perverse Methods of Guy Debord’s Mémoires“Ella Mudie, “An Atlas of Allusions: The Perverse Methods of Guy Debord’s Mémoires,” Criticism 58 (2016), pp. 535–63. and the research of Bart Lans and Otakar Mácel at TU Delft on the making of both Debord-Jorn books.Bart Lans and Otakar Mácel, “The Making of Fin de Copenhague & Mémoires: The tactic of détournement in the collaboration between Guy Debord and Asger Jorn” (Delft, 2009).

Explore the Book

This is a preview only - view fullsize on archive.org

Gallery