|

|

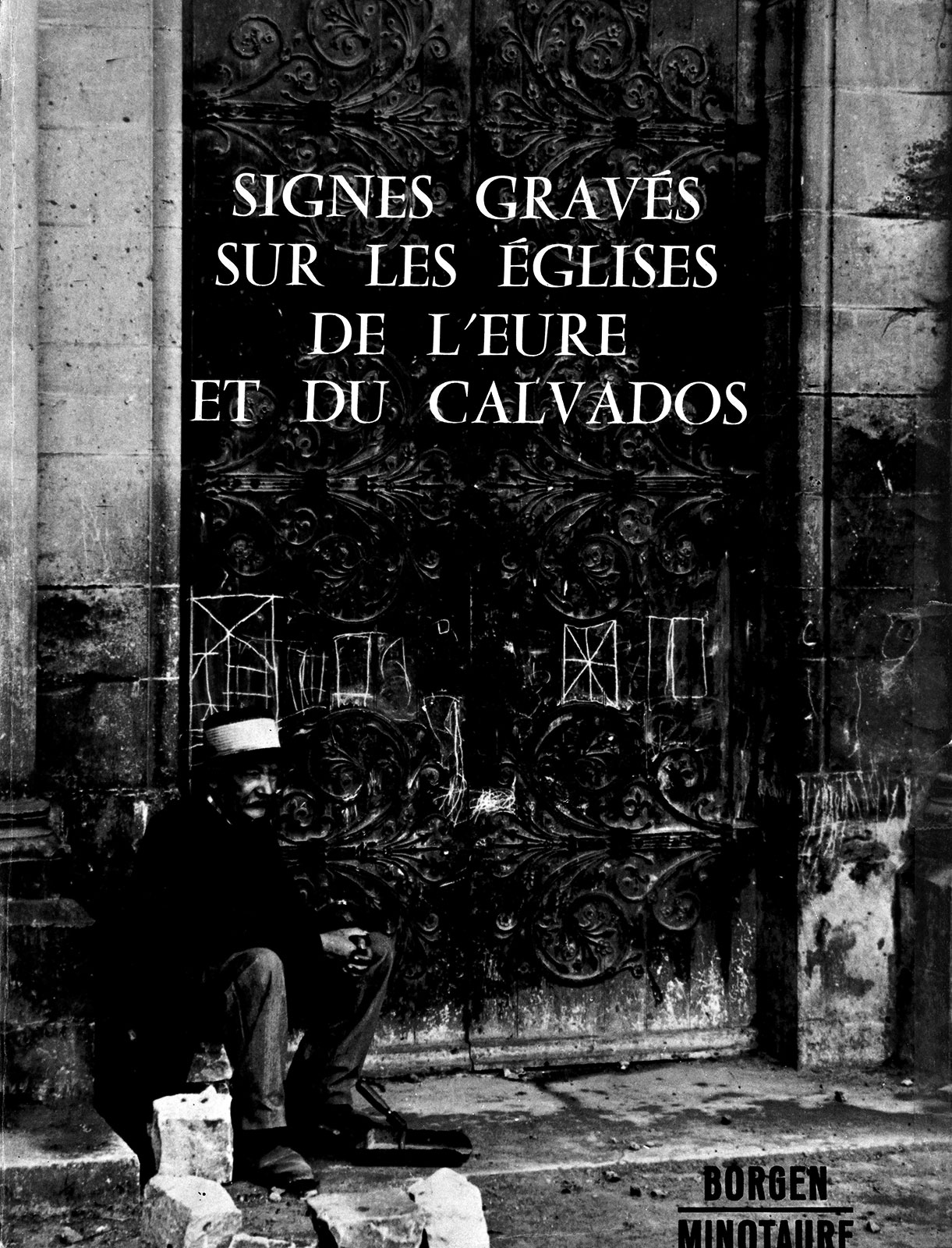

| Signs Engraved on the Churches of Eure and Calvados | |

| Authors | Asger Jorn & Gérard Franceschi |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Borgen |

| Publishing date | 1964 |

| Series | Library of Alexandria, Vol. 2 |

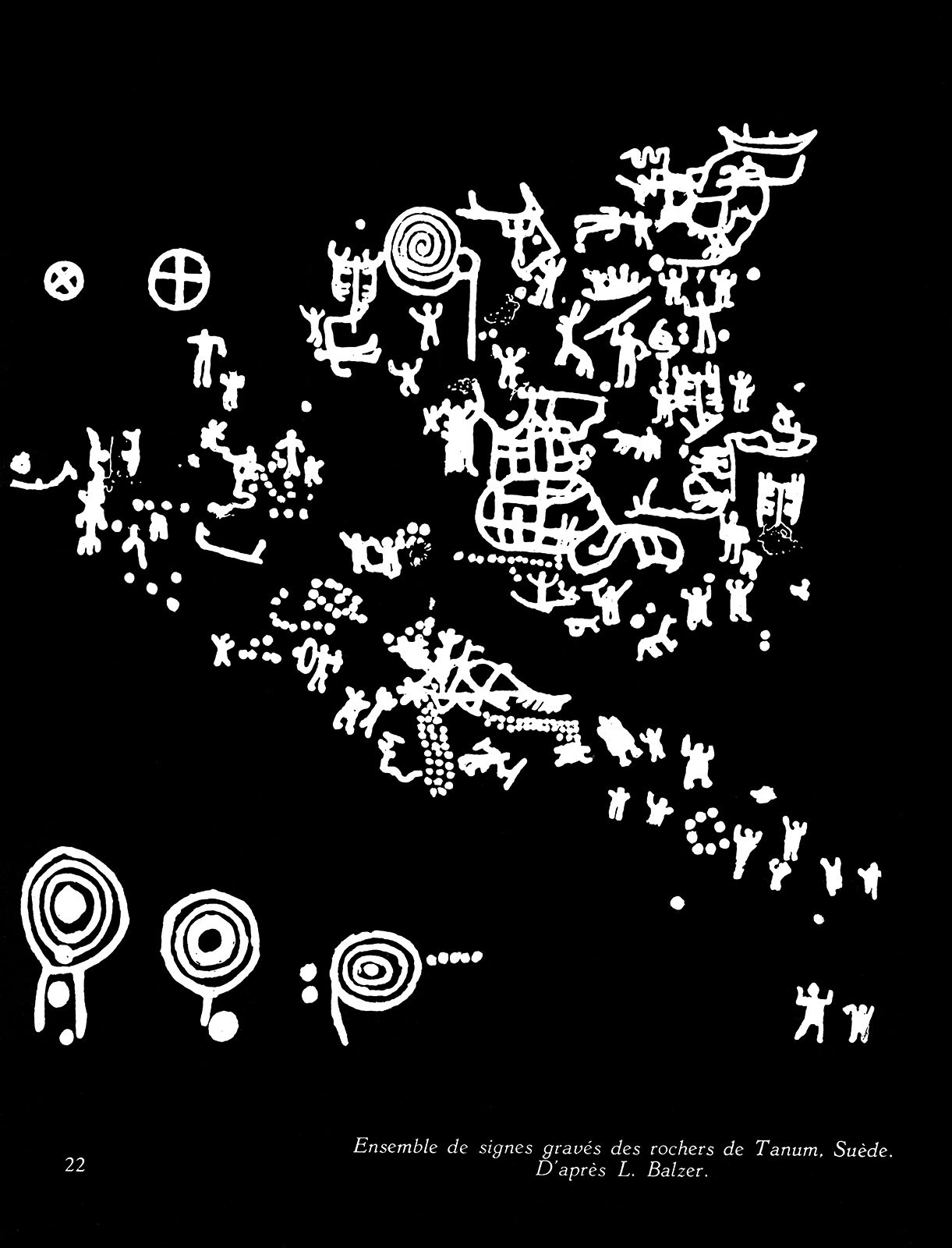

Signes gravés sur les églises de l’Eure et du Calvados (Signs Engraved on the Churches of Eure and Calvados) is a book written in French and directed by Asger Jorn, with essay contributions from various antiquities experts and photography by Gérard Franceschi. The book was published by Danish publisher Borgen in 1964 and distributed in France by Librairie ‘Le Minotaur.’

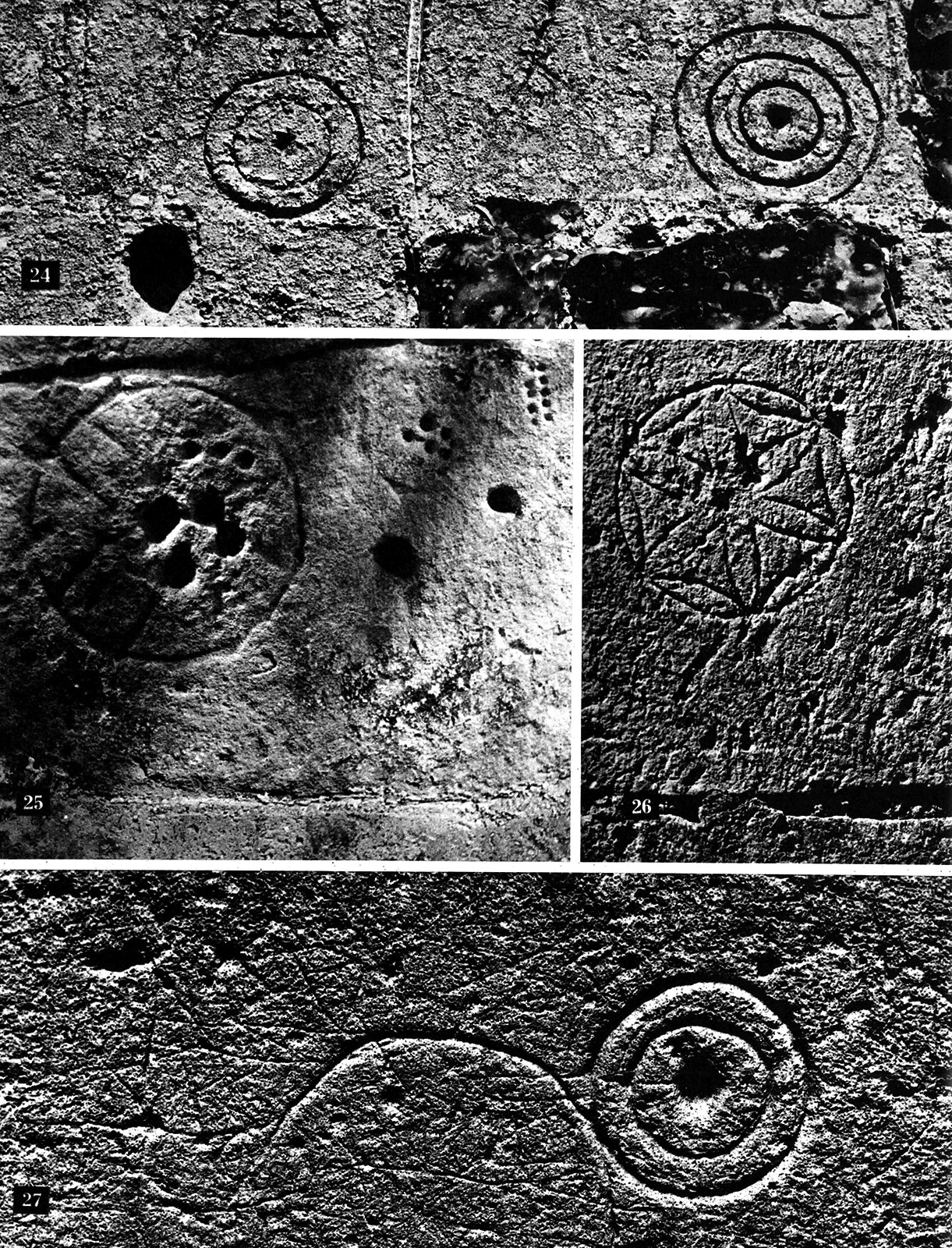

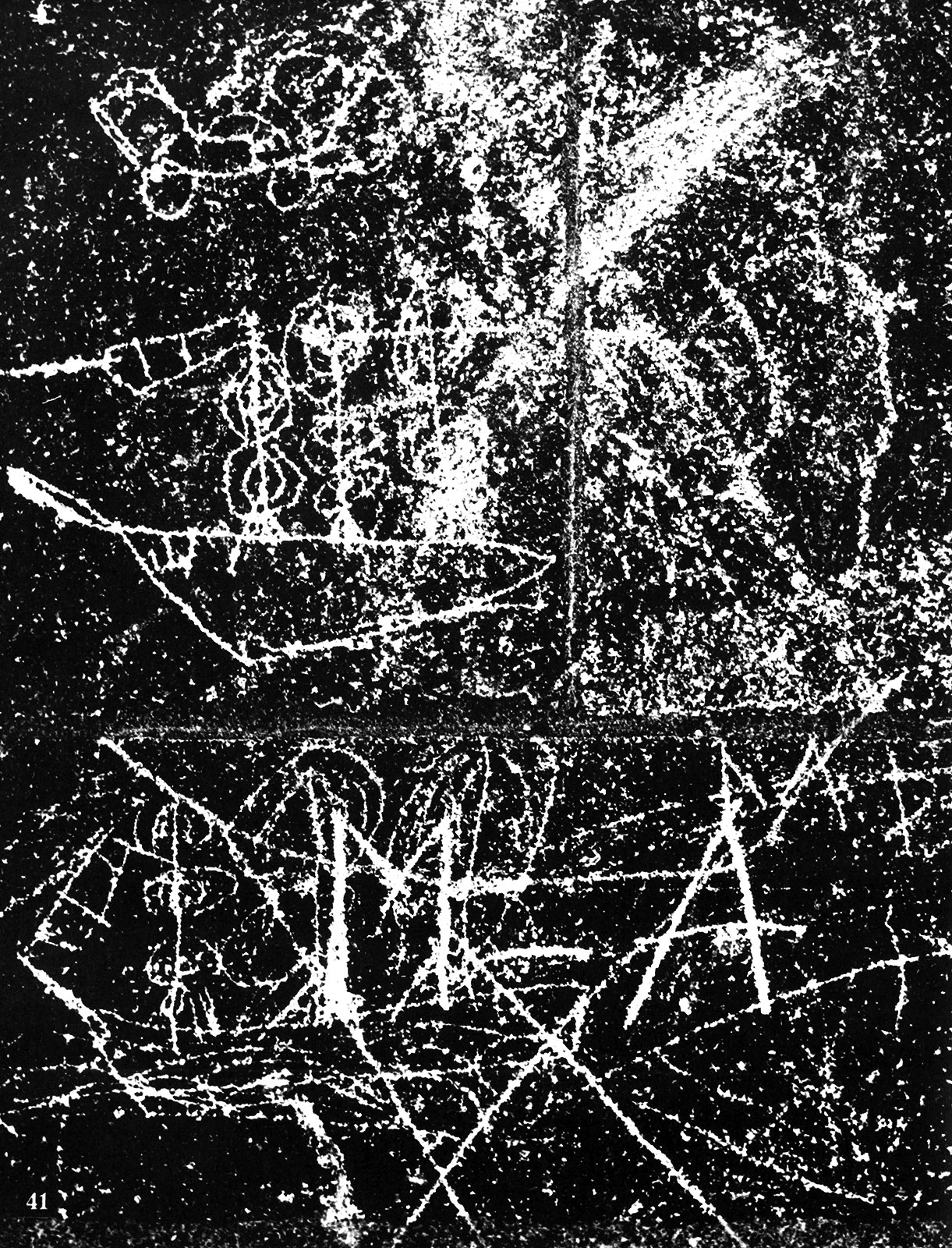

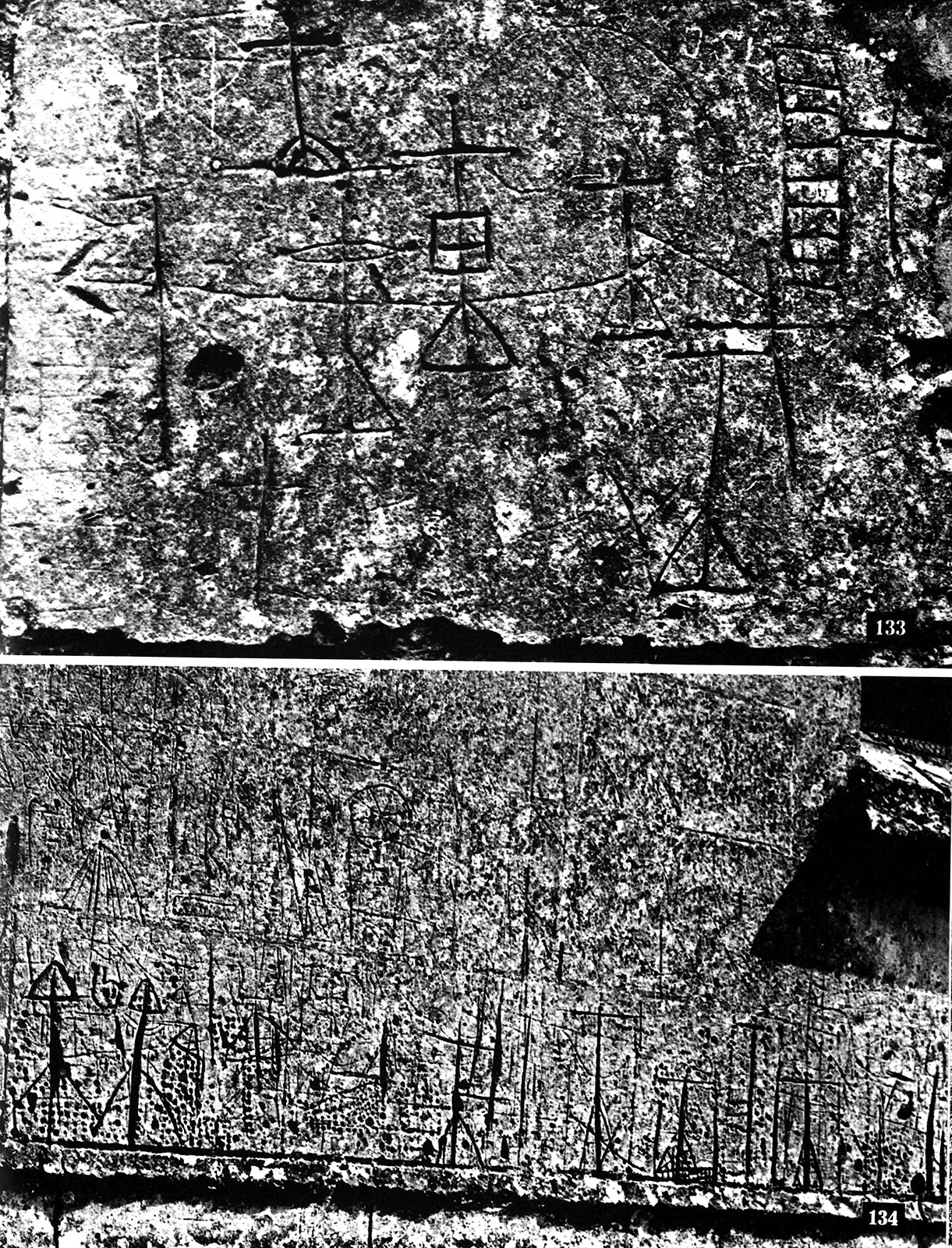

The book is a photographic examination of secular, pagan, and religious “graffiti” found hand-etched into church architecture in the Calvados and Eure départements of the Normandy region in northern France. Jorn was inspired to document the symbols he found after a visit to the church of Damville in 1946 while visiting the painter Pierre Wemaëre. Jorn further draws comparisons to similar symbols found in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway at the cathedrals of Ribe, Lund, and Trondheim. Franceschi’s photography is coupled with essays from Danish archaeologist Peter Vilhelm Glob, University of Caen Professor Michel de Bouard, historian Louis Réau, and Asger Jorn.

The book is part of the series The Library of Alexandria. Volume 1 consisted of a series of Situationist pamphlets, Volume 2 was Jorn’s book Signes gravés sur les églises de l’Eure et du Calvados, and Volume 3 was Jorn’s and Pierre Wemaëre’s booklet Le long voyage, and Le langue verte et la cuite.

Concept

Karen Kurcynski explains Jorn’s comparison of the symbols found in Eure and Calvados to the Scandinavian “Vandal” culture:

The book related to Jorn’s Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism, founded 1961, which attempted to demonstrate by photographing repeated motifs in ancient and Medieval art throughout Europe, that the visual culture of the nomadic Scandinavian “vandals,” usually perceived as mere barbarians, did not derive from southern Europe but in many cases actually inspired European visual forms. Jorn’s conception of “vandalism” retains the double signification of both a historic ethnic group and the general value of destructive tendencies in culture. Jorn writes in Signs Engraved that rather than simple destruction, graffiti asserts a common human “need,” that of expression as a fundamental human activity. He further argues that, because the Medieval church held valuable objects (such as reliquaries) outside of social circulation, anonymous graffiti on the church walls expressed a popular protest against the isolation of artistic objects from everday life. He thus characterizes graffiti as an art form that defies the institutionalization of art and its removal from common society.

- Karen Kurcynski, Expression as vandalism: Asger Jorn's "Modifications"

Steven Harris links Jorn’s fascination with engravings found on churches to Scandinavian expansion into Normandy:

Signes gravés sur les églises de l’Eure et du Calvados focused on graffiti carved into the stone interiors of Norman churches between the twelfth and nineteenth centuries, which it presented as an unofficial culture contributed over the centuries by worshippers, as they attended Mass or visited the churches for other purposes. Jorn was drawn to this graffiti for several reasons. On one level, he saw a resemblance between the kinds of marks made in these Norman churches over several centuries and the graffiti found in Scandinavian churches, which implies the persistence of cultural ties between Normandy, settled by Scandinavian peoples, and the cultural heritage of his homeland. (While Jorn was not a nationalist, he saw a specificity to Scandinavian culture that he wished to make available to others.) On another level, he was drawn to this graffiti as a popular expression that is also a commentary on, and a supplement to, the official culture of the Catholic Church.

- Steven Harris, How Language Looks: On Asger Jorn and Noël Arnaud's La langue verte

Contents

Signes gravés sur les églises de l'Eure et du Calvados

Read the complete text in French and English.

Read the full text →Explore the Book

This is a preview only - view fullsize on archive.org

Gallery