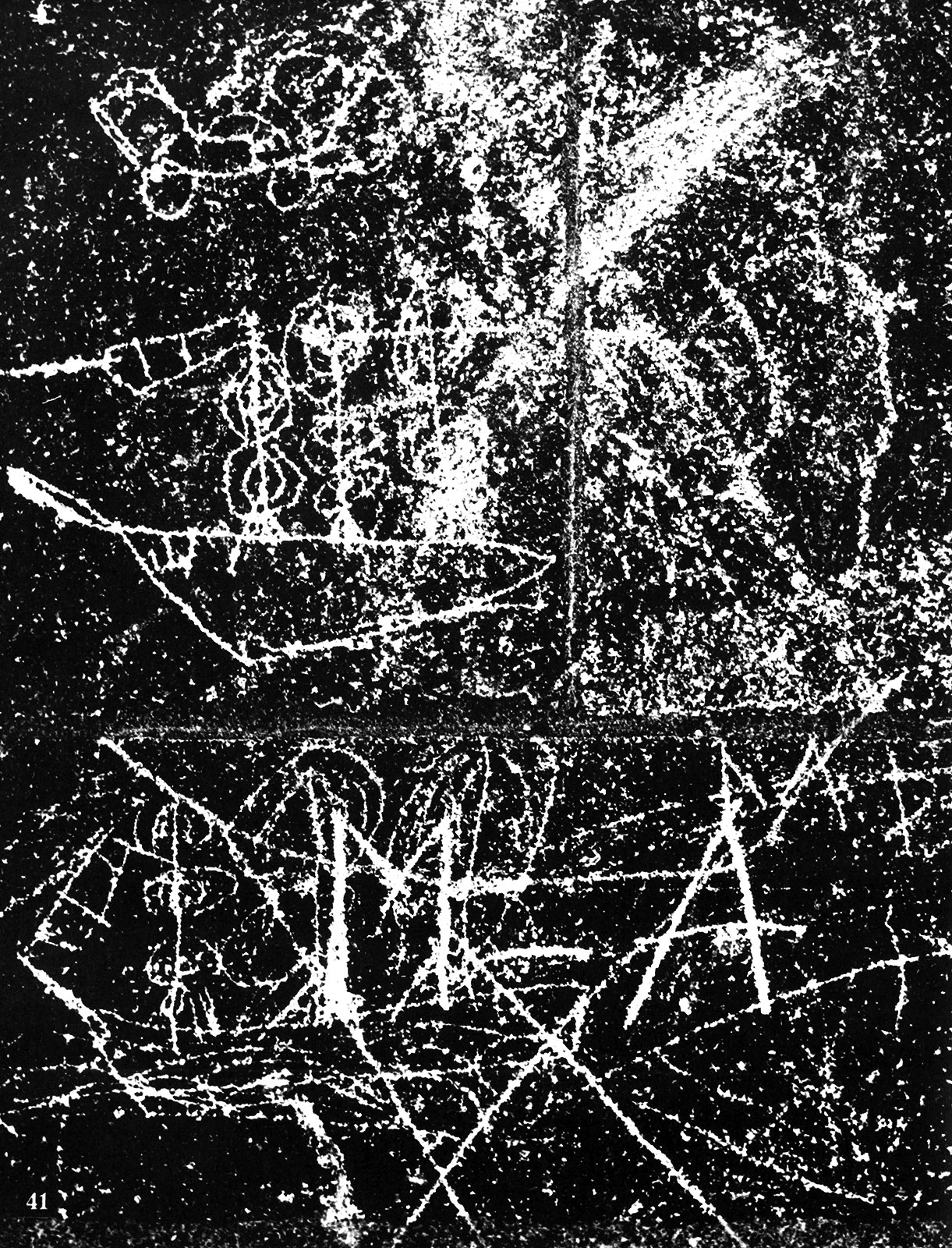

The images in this book are chosen from thousands of signs engraved or drawn on the walls of churches in Normandy. Among them are representations of churches and bell towers, but above all an abundance of crosses, generally placed on bases of different shapes. We even find the cock representing valour (numbers 64 and 67) or hearts, sometimes intertwined hearts. The fleur-de-lys can be found in a few places, or more gloomy motifs, such as the gallows where the evildoer hangs. In addition to this, a large number of subjects, apparently of no particular interest, belong to everyday life: horses, often with a rider, deer, birds, snakes, footprints, handprints, and an incredible number of small round holes in the shape of a cup. These subjects are not, by far, as insignificant as they seem. They are even more interesting than the rest.

Some of these figures are dated. One deer is dated 1753. A little higher up on the same wall is the figure of 1780 - and something, the last figure being erased (number 99). In another place, there is the number 164; maybe 1640. 1602 (?), 1620, 1740, 180 (?), but these dates do not correspond directly with the drawings. A rather precise indication can be found in the different styles, and especially in the different types of boats. This proves that the origins of these drawings are very diverse, from the Middle Ages to the end of the last century. The ship of number 59 seems to be engraved around 1110, whereas three-masted ships, frigate-rigged boats, schooners, bricks with all their canvas, sometimes sloops and even a coaster with a fork rigging can hardly predate the period around 1800. A ship with a wheel (the appearance of steam) confirms this. And the animal that turns its head to bite its tail belongs to the classic subjects of Romanesque art (number 114).

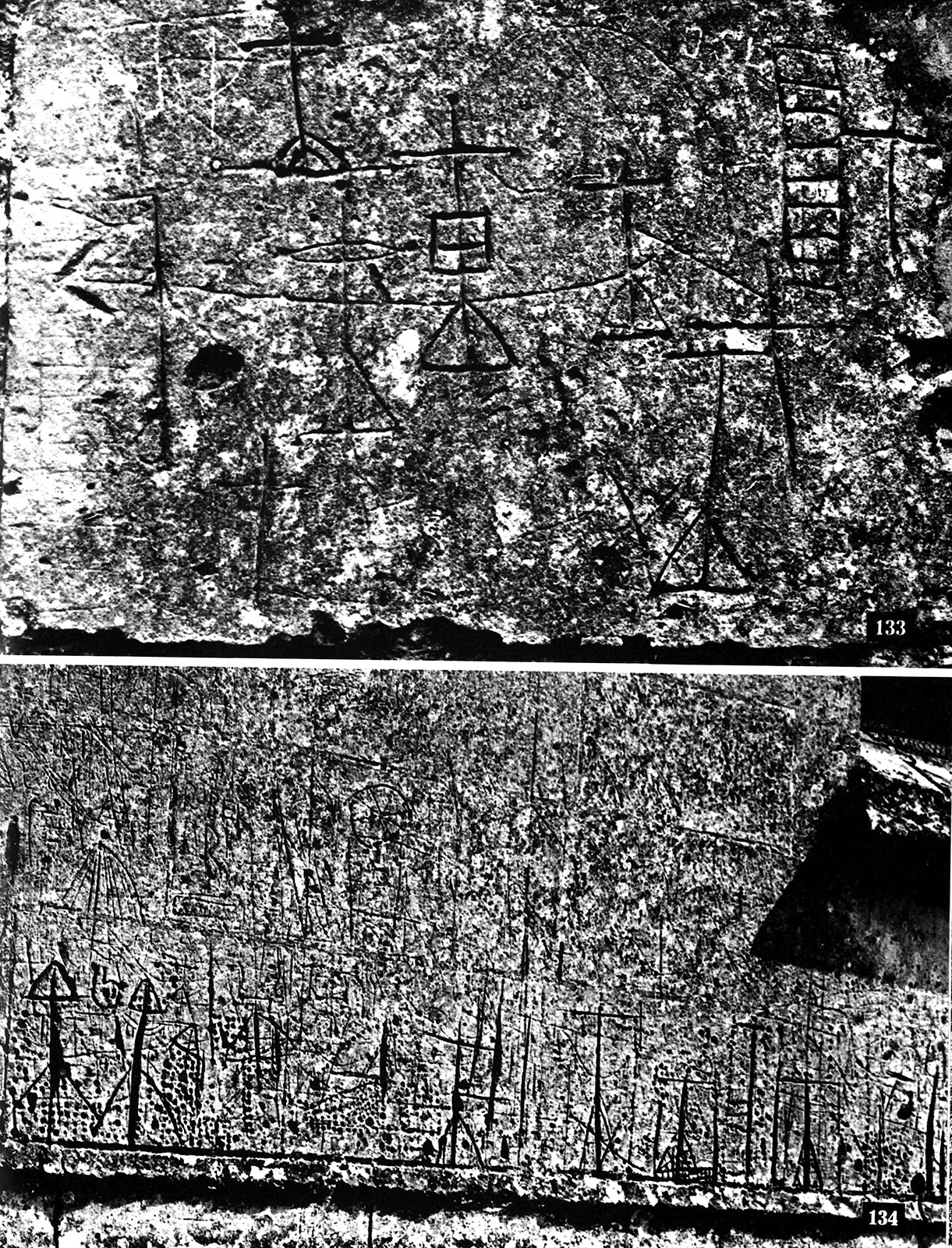

The superimposition of several layers of figuration also shows, through the chronological record of the making of the images which thus becomes possible, that long periods have passed over this undertaking. Even with photographs of remarkable quality, as they are presented here, it would be futile to attempt an analysis of the individual chronological layers on the basis of the photographic reproduction of the whole. On the other hand, it is highly unlikely that the establishment of such a survey could teach us anything whose importance could be weighed against the immense amount of work, and the long duration, that would be involved in researching the monuments themselves.

This is not a professional art of any kind. It is the simple man, more or less pious, who spends his time there waiting for the beginning of Mass; or more likely, after having brought his offerings, to the Saviour, the Blessed Virgin and the other saints. The images are hardly ever realized as works of art, in the sense that we currently give to this term, except in a few rare attempts where one feels a conscious aesthetic desire. This is most clearly evident in the rosette (number 173), where the tension between the square and the curves of the eight-leaf rose, together with the decided technique, shows that this is a “popular” artist with skill and nerve. Other figurations show the feeling of form and the safety of the hand, and achieve striking results. This is the case of several boats, such as the sloop number 46, the coaster (yacht?) number 48, or the brig number 58. Often the circles were executed with compasses of various kinds. This is especially visible with those with six-leaf rosettes.

However, it can be seen, as a dominant rule, that the essential concern is the image, the symbol, or rather the metaphor itself. Thus it is part of what is called folk art, in its most authentic form. The most ordinary people have felt the need to express themselves in images, to translate into them things that are elementary and central to the life of their interests and feelings; and with this, to bring to light associative images, which have arisen by apparent chance from the closed depths of their unconscious, and it is precisely this last part that offers so much interest.

Because the unconscious does not create associations in a vacuum. They are realized on the basis of supposedly “forgotten” experiences, and what constitutes traditions are precisely such erased experiences. In order to really be able to value the meaning of these images, we are obliged to make a preliminary clarification of what constitutes tradition in its ultimate foundation; and then to specify some data from the ancient history of Normandy, in order to be able to situate the traditions presented here.

Tradition encompasses everything that happens from generation to generation as beliefs, habits, ideas and images. It is not subjective in the sense of individuality, of belonging to particular men. On the contrary, it is an all-encompassing accumulation of experiences lived in society as a whole, thus representing a subjectivity common to all. This does not only characterize the small local society, but also larger ethnic units, the people or the nation. It even plays a role in what can be called the great cohesion of social culture: what is usually called “our Western civilization”, and what is characterized by the American Robert Redfiel as “the great tradition”.

Tradition accumulates elements from everywhere, and covers countless generations. But tradition is far from being static; it is constantly engaged in a process of transformation. New experiences are constantly being added, while others disappear.

Conscious intelligence is always individual and analytical, because attention to things is necessarily self-centred. Consciousness is like a lighthouse, which can send its ray of light everywhere, and thus cover the entire horizon, but only in small areas, successively. Tradition, on the contrary, is synthetic, encompasses everything, and thus takes on an apparently objective character, because all the contributions of the “forgotten” experience are melted into a great plastic unity, whose coherence is perfect in time as well as in space.

The whole process of traditionalization that has been going on since the beginning continues today, and continues into the future. What is forgotten does not disappear. It only sinks down to the subconscious and unconscious levels; and the events of yesterday are already on their way to the traditional mass. This process has been going on for a million years or even more, since tradition seems to be also a partially constitutive factor in animal behaviour.

True tradition is unconscious, because we live in it and are constantly being shaped by it. Once made conscious, it completely changes its aspect, it transforms itself into traditionalism, a phenomenon which plays a considerable, and largely dangerous, role in the dynamic modern world, which gives so little free play to true traditions, nor at the same time to the imagination. Combined with the expansive dynamism of our times, modern traditionalism develops a desire for national power that is alien to genuine traditions.

What is most difficult to define are the traditional elements which have come from, or have been bound together by, such broad cohesiveness, because in their case all the detailed elements of this great ensemble are so closely interrelated that they change character as they go along; thus they become very difficult to locate in the interplay of the whole. Local traditions, on the other hand, are often quite easy to show. As examples of such purely local traditions, we will mention a few cases whose incredible antiquity has been established by archaeologists. These examples are limited to the Scandinavian area only, but one could surely find similar examples in many other countries.

Archaeologist Karl Rygh reported, in his day, this: “In 1876 it was explained to me, in the Strinda country near Trondheim, that there was a legend that a knight in armour and his horse were under a large rock. He would have been surprised by a rock fall as he passed through the valley, and crushed. I took the trouble to dig under the rock as far as I could, and I did find the bones of a horse and a man, plus a lighter steel and two spearheads obviously from Viking times…. The presence of a grave was excluded. It must be admitted that the poor horseman, after his hasty burial, had been equipped with a harness and a knightly dignity that were also imaginary. The accuracy of the tradition is no less striking, considering that it was communicated over a period of a thousand years, and attached to a specific block of rock, among many others.

Even longer is the duration of the tradition concerning a large “Ottarshögen” mound in the commune of Vendel in Uppsala, Sweden. The mound is forty meters in diameter, and was mentioned as “Uttershögen” in 1670. In the years 1914-16, the mound was excavated by a specialist, Professor Sune Lindquist, one of Sweden’s most outstanding archaeologists. In the middle of the mound he discovered a tomb in which a wooden cup with gilded bronze fittings, calcified bones, game pieces and pieces of a bone comb had been placed. The find is fairly well fixed in the chronology by a gold coin of the Eastern Roman Empire’s coinage minted under Emperor Basiliscus (476-77). Since the coin was used as a pendant, and was quite worn, this leads us to propose a date for the construction of the tomb placed in the first decades of the 6th century. This period corresponds precisely to the time when the king of the Ynglinge family, Ottar Vendelkraka, died, following the genealogical line given by the “Ynglingatal”. Professor Lindqvist thus has good reason to argue that Utter’s mound in Vendel was the tomb of Ottar Vendelkraka. In a paler form, we see here the tradition being kept alive for 1,400 years.

To the north of Oslo lies the largest burial mound in Northern Europe; Raknehaugen in Ullensaker. It measures ninety-five meters in diameter and fifteen meters high. The tradition that a king was buried there is not, however, clearly proven by the excavations. The Norwegian archaeologist Anders Lorange had learned as a young student that a king was buried there between his two horses and then covered with several layers of carpentry. With youthful enthusiasm, he set about digging down into a shaft supported by wooden frames, and had reached a depth of sixteen feet when its entire construction collapsed. This happened, fortunately for him, at dinnertime. After this perilous adventure he began an attack from the side and was very happy when, on the east side, he found the skeleton of a horse sixty feet from the edge. However, there is nothing to prevent the hypothesis being correct that the skeleton came from a dead horse: since dead horses are not eaten, they were able to get rid of it by burying it in the mound. However, Dr. Sigurd Grieg, who systematically searched the mound during the years 1939-40, did not find a single grave. There was, however, one remarkable fact. There were three layers of roofing on top of each other inside, and calculations would suggest that they must have been made up of about thirty thousand pieces of wood. Radiological analysis suggests that the mound must have been made around the same time as that of Ottar, or perhaps some time after. But the tradition of the carpentry was in any case confirmed by reality.

In Denmark there are even older, and apparently true, traditions. In the old days, the people of Bolling County used to say that a chariot full of gold was buried in the marshland of the rectory in Dejbjerg. It sounded incredible. But when people started digging in the swamp in 1881 and 1883 they found not one but two tanks. Even though they weren’t loaded with gold their value is priceless. These are cult floats from the pre-Roman period. Ceremonial floats made of oak and ash, trimmed with bronze in the Celtic style. The carriages were deliberately destroyed and placed in the marsh as an offering. In this case we are dealing with a two thousand year old tradition.

A Norwegian souvenir finally, which is worth mentioning because it reveals a purely local tradition that takes us back in time to five or six thousand years ago. In Bomlo, south of Bergen, there is a small island: Hespriholmen. There is a curious large quarry dating from the period between the Mesolithic and Neolithic, from which stones of a very fine quality, dense and green in colour were extracted. Axes from this quarry are widespread in large areas of western Norway. As the axes are, in folk traditions, called ‘thunderbolts’, it seems that the name of the island must be related to the Viking period, and deciphered as ‘the place where the thunderbolts are sought’.

Thus we see that the traditional element can be kept alive, attached to a specific place, for thousands of years. No one should be surprised that these elements are embellished by the imagination, because it is precisely in the large, shapeless mass of traditions that the imagination seeks its raw materials, and the data it collects there can be combined in the most diverse ways. In the examples mentioned here, we are dealing only with traditions based on localized social units, without support in the general traditional cohesion. It is obvious that the latter is much more stable, much more resistant to attack, precisely because they are groupings covering larger areas.

A characteristic and important example of this kind is the powerful situation of the bear in the popular beliefs and medicine of the North. The bear has “the strength of ten men and the intelligence of twelve men.” That is its fame. Until the middle of the last century, a bear’s paw was used in folk medicine to facilitate childbirth, and even in this century it has been possible to obtain written evidence of the bear’s affinity for the pregnant woman and her abilities as a midwife.

The archaeological data also show us the dominant position that the bear occupied in the North, as a supernatural force and fertilizing power, from at least the Mesolithic period. Its importance in this field from the Palaeolithic period on the European continent has been confirmed by the evidence from the cave of Montespan, in the Haute-Garonne, where a bear carved in clay, but without a head, was found with a bear skull placed in front of it between its paws. The clay body also bore numerous marks of arrows and spears, or similar weapons. Here we can probably carry on a tradition as far back as twenty thousand years.

But in such a case, it is also a traditional consistency of enormous extent. From the Scandinavian peninsula, where the tradition has continued its intense and strong cultural life at least until the last two or three centuries, a bear cult in similar forms can be followed through the entire belt of Russian and Asian forests, through the Bering Strait to North America. There one can note its extension southward to Southern California, New Mexico and Arizona. While the Scandinavian bear had a preference for pregnant women, we learn from the Indians of the northwest that there are many experiences concerning the tendency of women to be seduced by a bear, and thus to give birth to one of their children.

Another stream of great traditional cohesion in the North is the subject of Indo-European influence at the end of the Neolithic period: the bear was replaced by the horse as the supreme power of fertilization for the upper class of Indo-Europeans. This position was held by the horse until the encounter with Christianity around the year 1000. The violent effort by which the new church erected a taboo against the habit of eating horse meat was therefore well justified, even if it was not a resounding success. Even today there are still many horseshoes above church entrances all over the North. This victory of the cult of the horse as a fertility power par excellence, among Indo-European masters, did not prevent the bear from continuing to survive comfortably in the non-Indo-Europeanized strata of the population, or even to impose itself even in the Indo-European tradition. Bear teeth were in common use in northern Norway at least until the 14th century.

It is also worth mentioning that this tradition - apart from the Paleolithic memories of the bear cult at Montespan - does not in any way link the North with the continent on the Western or Central European side, but rather links it to Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. There were many Asian influences in the Western European Paleolithic.

The bear tradition is thus placed in a position which differentiates it from the vital, and more present, traditions of modern European-American civilization, which are the classical traditions and those which manifest the influence of West Asia: the religious and ethical traditions of Christianity, which for their part were largely formed by Persian traditions. In art and thought, in addition to the Greco-Roman traditions, those of the Arabs and those of India are thus infiltrated, a mixture which still appears today. A rather curious trace can be followed in this line, among others in the field of currency terminology. Of the Roman gold coin, solidus aureus, solidus survives in the Italian soldo and the French sou, while aureus was left to the Scandinavians who kept it in the form of an öre. The sign of the English pound corresponds to the Roman libra, and that of the dollar is again that of solidus. Moreover the ancient Scandinavian silver coin ört was the Roman denarius argentus in the time of the republic. In the Middle Ages an intermediate variant, the ertog or örtug, was formed.

Even if archaeologists and historians are, for the most part, aware of this strange tenacity of the life of traditions, one has the impression that almost all of them look upon it as a curiosity without scope rather than as a fundamental reality for the most important part of cultural formation. The time seems to have come when we must begin to give this phenomenon its true value.

Traditional coherence can legitimately be seen as a global unit without precise boundaries, with elements of widely varying length and importance. There are elements that seem to be quickly disappearing, hardly ever mentioned. At the very moment of the event itself, it is already moving towards unconscious unity. So that tradition is more or less identified with what Emile Durkheim called, in his time, collective consciousness, in a profoundly revised sense of course. What Durkheim did not know was the unconscious and subconscious power of tradition. For him, social consciousness was rather a kind of social soul of individual character. It is what thinks, feels and wants, even if will, feeling and thinking only act through single consciousnesses, he wrote in “Sociology and Philosophy” (1925). At the same time, we can see in the concept of tradition a greatly modified reformulation of Adolf Bastian’s old Völkergedanke, or popular thought, while his Elementargedanken, or elementary thoughts would be found, in a modern formula, closer to the archetypes of Jung. For Bastian, the elementary thoughts were universal ideas common to all mankind, ideas which would have the same character in all times and among all peoples, whereas for him the “popular thoughts” were particular forms, which the system of elementary thoughts must have had, under the diverse influences of the natural environment. Popular thought” would thus represent a layer of creative and formative forces beneath the different forms of culture. Probably no one would accept Bastian’s ideas today, because they are too naive and simplistic. It should be noted that Durkheim’s criticism was precisely an argument against the attitudes supported by Bastian and Wilhelm Wundt with his Völkerpsychology.

Leaving aside for a moment questions of tradition, we will indicate some features of the ancient history of Normandy. It is quite well known that the name Normandy is due to the Danish and Norwegian Vikings who plundered this region around the year 800, and then settled in the country. In 911, their chief Rollo (Gange Rolv) received the country in fief of Charles the Simple, and the Norman state was established. There have been quarrels between Danish and Norwegian historians about the mutual importance of the two peoples in this endeavour; and above all, of course, about the probable origin of Rollo. This dispute is apparently as futile as the one over the Pope’s beard. All that has been proved is the participation of two peoples; and the fact, indicated by documents, that the Vikings of Vestfold, southwest of Oslo, attacked France (the Westfaldingi) on several occasions.

We are more informed about the development of this new Norman state. We know the profound influence that this new sovereignty has had on the social and cultural structure of the country and, moreover, on the political and cultural development of the whole of Western Europe. The least important was not the seizure of England by William the Conqueror in 1066, nor the Viking possessions in southern Italy and Sicily, and their participation in the Crusades. Their Norman strongholds were conquered by Philip Augustus in 1204 and submitted to the French Crown in 1364. This did not prevent Normandy from enjoying an autonomy throughout the Middle Ages that gave its local culture a strong particularity; this was manifested, among other things, by the unparalleled efficiency of its administration.

Of all these facts, the Nordic memory has above all retained the particular forms that Romanesque architecture received from the “Norman style,” which was to dominate England, and which profoundly spread its influence in the Scandinavian countries.

This new springboard does not detract from the fact that tradition in Normandy has retained many elements of its Nordic origins, both in language and customs. Place names such as Turville are still reminiscent of the god Tur or Tor in whom, according to ancient documents from Normandy, the Vikings had faith.

A legend, which finds its poetic form in an ancient French poem, tells that Arletta, the mother of William the Conqueror, when she gave birth to him, dreamed: “A tree grew out of my body. It was rising towards the sky. It cast its shadow over the whole of Normandy”. This is a copy of the legend of “Queen Ragnhild’s Tree”, the tree that appeared in the dream of the wife of a small local Norwegian king, Halvdan Svarte, when her son Harald Haarfager, who was to reunite Norway under her rule, was born. She dreamt that she was in his garden, and that she was removing a thorn from her dress. The moment she held it in her hand, the thorn began to grow, to become a big tree. The tree touched the ground, took root there and grew very high in the sky. At the bottom the tree was red as blood, the higher the trunk was bright green, and the branches were white as snow. It had many strong branches, some high and some low. The branches of the tree extended so far that they covered the whole of Norway.

The heroic poems of the Edda songs found a renaissance in Normandy, and contributed to the compositions of the heroic poetry of the French Middle Ages, but by abandoning the Nordic language, which was soon replaced by French. Already Rollo’s son Wilhelm Langsvärd was obliged to send his sons to Bayeux to study the Nordic language, which had begun to degenerate in Rouen. Much more important for the tradition were the survivals of paganism, which, independently of official Christianity, remained an underground and illegal cult. It greatly disturbed and frightened the pious ecclesiastical souls.

The mention of these few survivors of the Nordic influence in Normandy is made for no other purpose than to show how traditions can retain ideas, or at least their symbolic forms, through incalculable epochs; and to sketch a little of the character of the traces with which the Normans were able to mark the new country where they settled. The historian of Normandy André Manguy, when he was finishing his book “Au temps des Vikings… les navires et la Marine Nordique d’après les vieux textes”, published in 1944 during the German occupation, was touching on the heart of the matter with these sentences which seemed in truth to appeal to his “Scandinavian brothers:” “to teach a world reborn all that our ancestors understood by the word aere, which has a meaning close to that of honour - the true basis of social and moral life in the ancient Nordic people”.

Probably the time has come to return to all these signs, so discreet, almost insignificant, engraved or carved on the walls of Norman churches. But, seen in the light of tradition, we must first recognize the synthetic, almost amorphous character of this slowly moving unity of coherence, in order to be able to situate the signs on this basic unity in our attempt to valorize it.

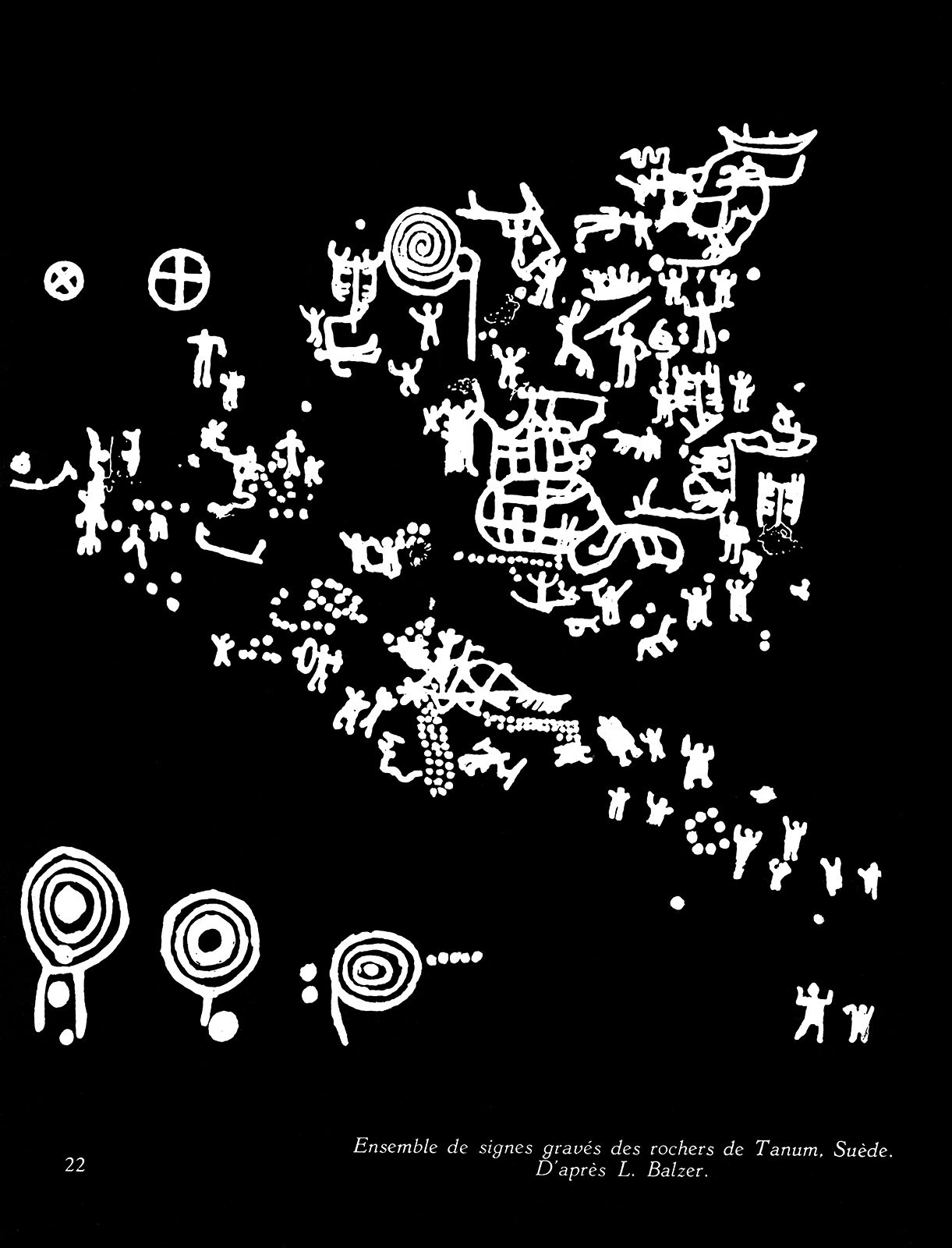

The first impression that struck me when I saw these images was this: “Tudieu! Here is the whole gallery of subjects of the Scandinavian Bronze Age rock engravings.” It is obviously tempting to try to establish the possibility of such a traditional coherence. The very idea may seem to most people to be more of a dilettantism than a baroque one, since the normal method is to analyse each subject in isolation, and in this way it is naturally easy to explain that “circles were made always and everywhere”, or ships, or figures, or hearts, or…, etc., etc. One is of course right in the sense that such a hypothesis can in no way be proven by following the classical demonstration of probability methods. Nevertheless, we have amply demonstrated how tradition is capable of an incredibly tenacious vitality, and another fundamental condition must be kept in mind: when a tradition is transplanted into a new environment, it is often marked by a tendency to sclerotize, to harden and to close in on itself in an immutable form. We have an example of this in the surprising conservatism of the Nordic language in Iceland and the Færø Islands. There we feel the rupture of contact with the place of origin. Norwegian writing has never been so perfectly Danish as after the dissolution of the union in 1814. It was only after 1907 that it slowly began to regain its original character.

It is indisputable that leafing through these pictures one finds almost the entire repertoire of subjects from the Bronze Age rock engravings, obviously in a somewhat attenuated form. What characterizes above all the Scandinavian rock engravings are subjects such as the boat, sun signs, cup-shaped hollows interpreted as offering cups, horses, ploughing scenes, deer, snakes, men in various attitudes and situations and horsemen, foot and hand prints. All these people are present on the walls of the churches of Normandy. Various subjects are obviously missing from the rock engravings, notably the fir tree - the eternally green tree - as a symbol of fertility, the importance of which is of course secondary in a country with deciduous forests (if one cannot interpret numbers 62, 127, 128, 131 and 178 as firs). Also missing is the chariot, so common in rock engravings. What is most striking in these Norman-Scandinavian relationships is the resemblance that can be found in the very forms of each sign. This is what we will study in our comments to the particular images.

There is no longer any doubt that the Nordic Bronze Age rock engravings represent a cult of fertility linked to agriculture. The sun takes a dominant place here. The sun that crosses the sky at night in its boat, but in the daytime rides the solar horse, as is best expressed by Trundholm’s famous solar chariot from the early Danish Bronze Age.

The tradition of the solar boat was obviously maintained in the North until an incredibly late period. In my own youth, before and during the First World War, it was strangely important for us, in the village in western Norway where I spent my early years, to find an old boat and place it at the top of the Midsummer bonfire. I think there is no objection to the idea of considering the fire on the night of the summer solstice as a festival whose origin lies in the cult of the sun. None of us knew why, nor did any of us start thinking about why it was necessary to have this boat. It just had to be there, that’s all. There were some years when it was a hard ordeal before we could beg enough to get an old rowing boat for our ceremony. Later I learned that the same game was being played in other parts of the country.

In this regard, there is a study to be done on the question of the presence of boats in churches. The old hypothesis, which is still valid, that they represent ex-votos of sailors who have survived shipwrecks, is not sufficient.

It should be noted that ritual summer solstice bonfires are an ancient and general tradition in the North. The one on the island of Runöe in ancient Estonia is said to date back to ancient Swedish influences. Such traditions are unknown to me in Normandy, I must confess. James G. Frazer, however, mentions in his famous book “The Golden Bough” a strange custom of Saint-Lô, where a burnt human effigy is thrown into the river, where it floats away while being devoured by the fire. This tradition has been interpreted (by Oscar Almgren) as a mixture of the custom of burning the god of fertility at the stake of the year, and his disappearance on the sea in a boat.

Thanks to its important role in the sun’s march through the sky, the horse too sometimes takes its place between the sun signs, but the horse remains above all the image of the procreative force. This is a phenomenon common to all Indo-Europeans, well known in ancient Hindu rites where this symbolism is extraordinarily obvious. The Rigveda means the sun as a disc or wheel pulled across the sky by the horse Etaca (the ballast) directly harnessed to the disc. The horseshoe on two of the pictures in this book (numbers 76 and 77) thus has the function of signifying the horse.

The relationship between the horse and the boat is obvious. It is not by chance that in the old Edda, in Nordic poetry, the boat is continually referred to as a horse: “horse of the sea”, “horse of the waves”, etc. The horse is also referred to as the “horse of the waves”. It is an idea that has its origins at least in the Bronze Age. A rock engraving in Ostfold, Norway, shows a boat on which several sun signs are superimposed. The bow is undoubtedly shaped like a horse’s head, with a long floating mane, while the rear of the boat is a ponytail.

The deer also appears as a sun sign. The solarhjortr of the Eddas. The sign of the celestial god Ty. In a rock engraving from Bohuslen, Sweden, two deer are connected by a band, or something similar, and one has a sun wheel on its horns. And even this image is among those that have a very large extent.

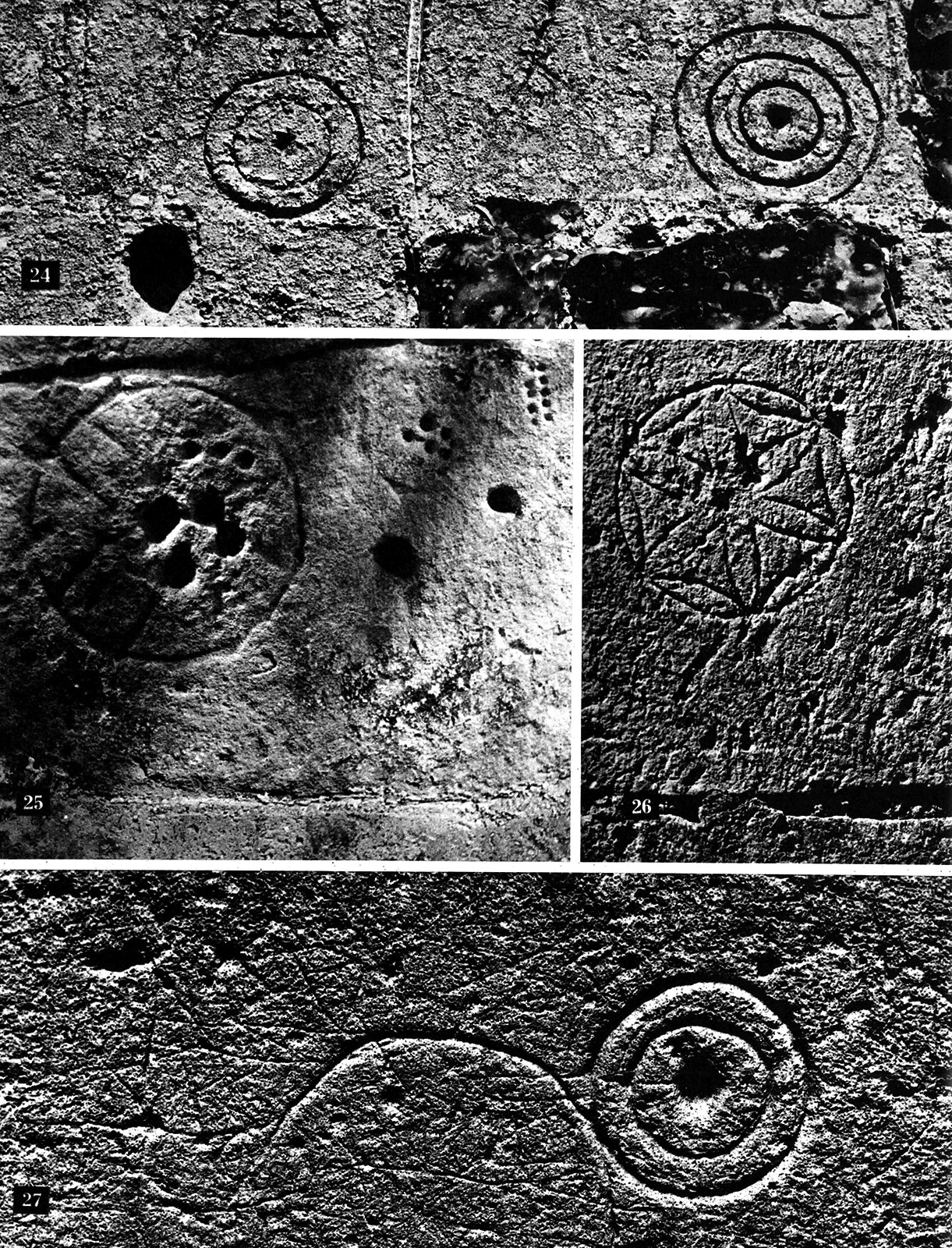

The sun sign itself is often a wheel with four spokes. Concentric circles are also common (cf. Numbers 24 and 27). Sometimes two concentric circles are encountered, with spokes close together (cf. number 91). Sometimes the circle itself is composed of a tight gathering of cupuliform hollows (number 92). Sometimes a figure is depicted with a sun wheel as a head (number 92). Here we are in the presence of the anthropomorphised solar god himself in the arena of rock engravings. One or more sun wheels are often seen passing directly over a boat (cf. number 39), or being pulled by the sun horse.

In Norway at least, it is striking that rock engravings are so often found in places called Solberg, the solar mountain. There is every reason to believe that such names are so ancient that they were attached to the sacred mountains where the sun was worshipped. Engravings are also found in places called Helgaberg and Helgastein, the sacred mountain and stone.

The links between the sun worship and the fertility of the land are easy to detect, considering that the engravings are carefully placed on rocks surrounded by arable land, or on cliffs facing pieces of land with this character. It is therefore natural that ploughing scenes are often found among the engravings. Whether these are religious agrarian rites, this is clearly revealed in an engraving by Bohuslen, in which the farmer holds a small fir tree in his hand during his work. Its eternal greenery was a sign of the fertility of the land in large parts of Europe. We often find the fir tree as an independent image on rock engravings. It even seems to have survived its encounter with Christianity in Germany, where it was known throughout the Middle Ages, and from where it later found a renaissance that spread to Europe as well as North America as a Christmas tree. Even this ploughman, we find him here (number 94). He works with a wheeled plough, long used throughout Europe. It was brought to England by the Angles and the Saxons.

Footprints are an extremely common subject in rock engravings. Hands are also found there, but more rarely. Here we are faced with an almost universal representation, because footprints of humans and animals can be found almost everywhere on earth, and handprints are at least as common. In Europe this representation dates back to the oldest Paleolithic art. Without commenting on the discussions on the interpretations that have been put forward for these signs, which are normally based on conjecture, it should nevertheless be mentioned that they are both part of the set fixed in the subjects of the rock engravings as well as that of the churches of Normandy (numbers 68-76, 78-83).

From time to time, one comes across a figure with enormous hands in the rock engravings. He has been called “the god with big hands”. Dr. Just Bing considered that he represented one of the two great Indo-European gods, who was “the god of fire” and “the god of heaven” (the “god with large hands” corresponding to the first mentioned). But his arguments were, once again, so based on his desires that there is little reason to retain them. There is, on the contrary, every reason to draw attention to the strange figures with big hands, numbers 84 and 85. The 84 is of special interest, being additionally equipped with a large spiral “sun form” on the belly.

The most common subject of the northern rock engravings remains the cup-shaped hole, interpreted as an offering cup. In rock art, this is a subject as widespread throughout the world as foot and hand prints. The holes are gathered together in thousands, and often placed in relation to each other in a precise composition. They can form solar images. There is a large wheel on a Bohuslen engraving where the inner spaces are filled with tight holes. Is this the celestial wheel with the stars? A primitive zodiac?

Who knows? In a Norwegian engraving by Ostfold we see a long, narrow path of holes that climbs up the mountain to surround a sun sign. Is this the Milky Way? It does not seem that an absolute dependence is logically necessary between the holes and the solar cult proper, and at least not directly between them and the agrarian cult of the earth, since these holes are found among the rock engravings far away in the high mountains of Norway, where any possibility of cultivation is excluded or, at best, would have encountered extremely unfavourable conditions, even in the hot climate of the Neolithic and Bronze Age.

Yet another subject dear to rock engravings is the snake. It stands on the ship as well as in front of men in a posture of adoration. He too participates in the general worship of the sun and fecundity. On work calendars (runic sticks) in Sweden, the day of the spring equinox - March 21 - is sometimes represented by a snake (Ostergotland and Kalmarfaif ), and sometimes by a plough (Uppland ). This established link is not without interest since a rock engraving by Bohuslen shows a close combination of a snake and a plough. Fertility and death are only two sides of the same coin, and in this relationship the snake plays a considerable role in Nordic beliefs, as well as in those of Russia. But since the snake belongs to the group of great universal signs, its particular interpretation over a limited area is very difficult to establish. The relationship with this world can be seen in numbers 10, 30-31, 33-35.

Thus we have examined the close relationship between the main subjects of the Nordic rock engravings and those on the walls of the churches of Normandy, this does not of course imply at all that a direct relationship between the two has been proven. Seen against the background of all that has just been explained about traditions and their behaviour in general, it seems, however, that we can see that all this reveals at the very least a problem whose solution would be of considerable interest.

Should such a direct relationship be suspected, there is in any case an important reservation to be made. It is absolutely excluded that Bronze Age religious philosophy could have been a conscious spiritual force in the Normandy of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. What could have been, at that time, the conscious interpretation of these signs? For example, can the relationship between the sun and the image of the church be considered for landscape design purposes (numbers 160-161)? Against this eventuality speaks the fact that the sun sign is found in combinations where such interpretations have very little natural basis. Its relationship with the crosses indicates other ways of interpretation.

Analytically, the study that I present here has two bases of equal importance: the principle of complementarity highlighted above and the concept of field. The latter was developed by the American psychologist Kurt Lewin, “Topological psychology”. Having realized that no socio-cultural system is a closed and isolated system, I believe I have sufficiently emphasized the dynamic value of this concept of field. There is no such thing as a closed field. There are always superimpositions, juxtapositions, overlappings between systems. The permanence of a field of tension implies the existence of real possibilities of transformation and renewal. The thesis that I developed in “Socioculture” (1956) seems to us to be in a perspective close to Jorn’s “situlogy”, a situlogy conceived as a dynamic or experimental topology.

The non-traditional examination of the nature of intellectual consciousness reveals the importance of the principle of complementarity. Let us return to the classical image of consciousness. A lighthouse whose narrow brush of light successively sweeps the entire horizon. From any sector of this horizon, however considerable the light projected by the attention, it would be impossible for us to have any image of it if the rest of the horizon was not simultaneously present as if by the glow of a night light. Essential complementarity which is inscribed in the very simultaneity of these two different levels of consciousness, one precise, the other diffuse.