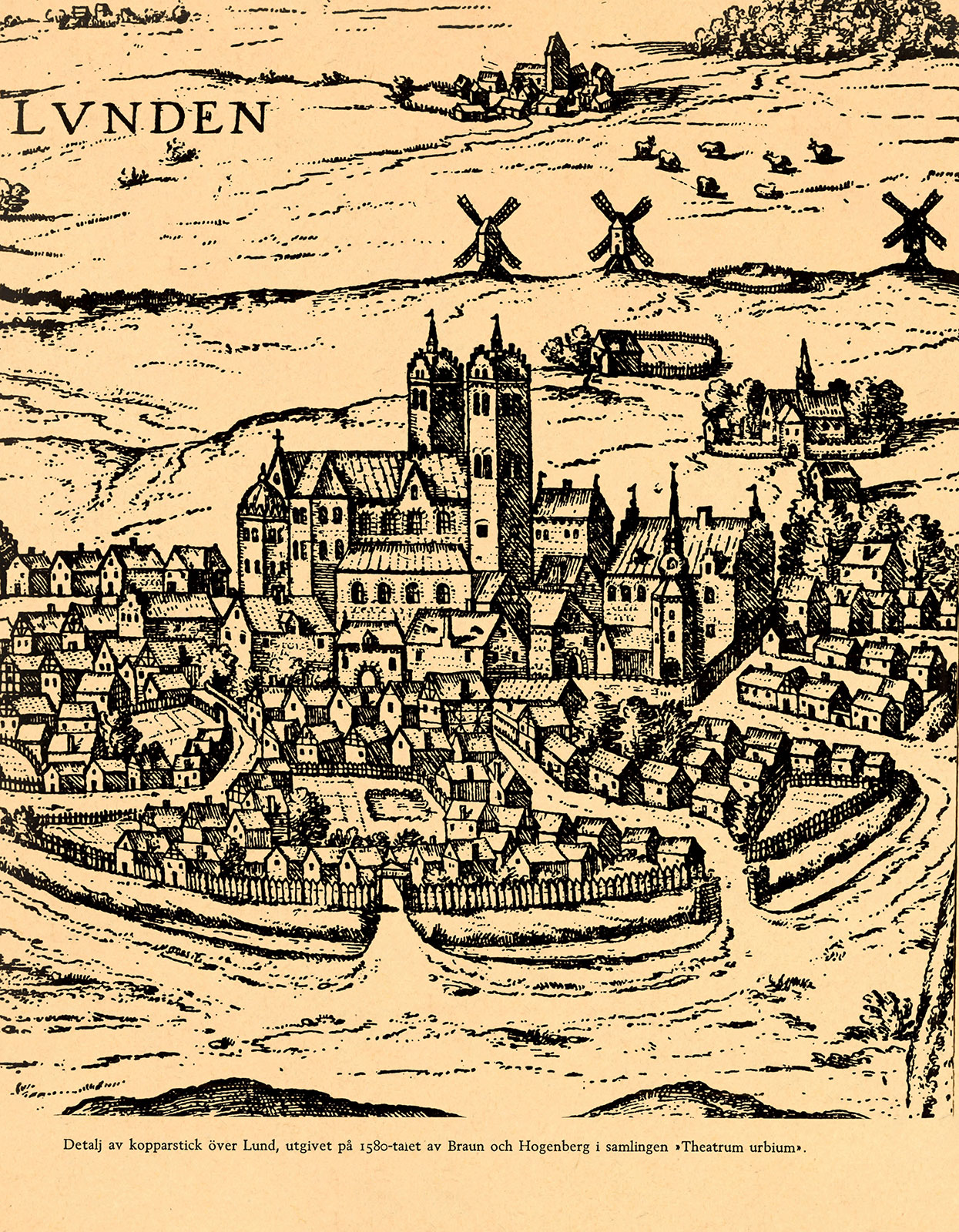

The medieval archbishopric church in Lund was not only at its inception, but is still the foremost Romanesque church building in the Nordic countries and of international importance. The new archdiocese, founded around 1104, was the prerequisite for its creation. The expanded liturgical function placed increased demands on a larger church, but the building would also, as a visible sign, assert and manifest the new position that the bishop’s seat would occupy. The construction of the new archbishop’s church seems to have started immediately. We know quite well how the work progressed through the fortunate fact that in our time a contemporary calendar has been preserved, included in the Necrologium Lundense manuscript, in which notes on the oldest altar inaugurations have been inserted. In 1123 the high altar was thus inaugurated in the crypt of John the Baptist, the glory of all patriarchs and prophets. The magnificent crypt room under the sanctuary of the high church, cows and transept was not thus complete. That was the first time the inauguration of the altar in the south side chapel. This happened in 1131, and the mention of this also states that the relics of the old church were transferred to the new crypt altar. This meant that Knut the Holy Church was allowed to remain at the place where the new Archbishop’s Church longhouse would be erected, until the crypt could be put into use as a full church location. that the relics of the old church were transferred to the new crypt. This meant that Knut the Holy Church was allowed to remain at the place where the new Archbishop’s Church longhouse would be erected, until the crypt could be put into use as a full church location. that the relics of the old church were transferred to the new crypt. This meant that Knut the Holy Church was allowed to remain at the place where the new Archbishop’s Church longhouse would be erected, until the crypt could be put into use as a full church location.

Through a death note in the Necrology we also know the name of the builder who led the work on church planning and earliest construction. His name was Donatus and at one time referred to as both architect and building manager, two titles that collectively gossip that the man was possessed of non-inferior skills. That part of the church, which was planned and erected under his direction, is characterized by a simple but powerful and harmonious architecture. Some sculptural decoration was only exceptionally created during this stage, from which still mainly the crypt but also the westernmost part of the longhouse remains. Unfortunately, the lower part of the tower section, which was probably erected at the same time, was torn down to the ground during the 19th century when the present towers were added. Of course, there was no domestic tradition of construction for a building of this magnitude, but the impulses were taken from outside. They seem to have come from the areas around the English Channel, the areas with which Denmark has traditionally been in contact through their Norman kinsmen.

Since the once stately cathedral of the modern environment lost some of the earlier more prominent rise, apart from the crypt, it is not primarily the architecture of this first stage of construction that today gives the cathedral its distinctive character and much of its fame. Instead, it has largely become the rich sculptural world, which, although somewhat decimated, yet richly represented, meets even glances at most places inside the church and around the medieval entrances. These sculptures make Lund Cathedral an outstanding monument in Northern Europe, a monument to the craftsmanship of the Romanesque stone masters, a fantasy of symbolically depicting supernatural forms of presence and of an internationalism that in the church’s fence was not inhibited by any geographical distances.

During the 1130s, the new stage in the church’s building history may have begun, during which architecture came to be adorned with this sculpture of almost Italian origin. It was during the same decade that Donatus died, but also Archbishop Ascer.

However, despite the bitter power-political struggles, the success of Eskil continued work on the cathedral. The older plan did not change, but some modifications were made to the church’s erection. The most significant change, however, was the now prominent sculpture in all important places in the building. On September 1, 1145, Archbishop Eskil was able to inaugurate the High Church and its altar to the Virgin Mary and Saint Laurentii. In the altar titles of the two side chapels, the patron saints of the church came to receive as flanking drabbands the two deacon saints Vincentius and Stefanus, who were in turn assisted by their warrior saint, Vincentius of the English Albanus and Stefanus of his mother Mauritius, all through their relics present in the south, respectively. north altar.

As a building, the cathedral was not finished with the inauguration of the high altar 1145, one of the aforementioned side altars, which in the north was inaugurated only the following year. The completion of the easternmost part of the longhouse, the site on which the older church from the 11th century still remained in 1131, should not have taken place until the end of the 11th century. But during the decades immediately before and after the middle of the century, most of the sculptural decoration has certainly been added and the abside exterior is completed. Although a lot of sculptures must be considered to have been lost over time, most of it remains from this time. Most are in their originally intended locations, such as the pictures of the preserved portals and the capital of the longhouse, but much has also been changed. This includes, for example. the notable lion and seraph sculptures of the Northern Transept and the reliefs found in the Cathedral Museum. Where these were originally found may be difficult to determine, but it is possible that they were intended for the interior of the church and marked the entrance to the Most Holy Place, to the Sanctuary. It is also possible that it was already Archbishop Absalon who moved them to their present places in connection with a reform of the cathedral, which he undertook in 1187. This would mean that the pictures were connected with a liturgy, which was then abandoned but at the same time, their expression value was so marked that they were allowed to do a new service in the church. It is perhaps no coincidence that they then got their place in the church hall, which apparently served as the Archbishop’s special chapel. Where these were originally found may be difficult to determine, but it is possible that they were intended for the interior of the church and marked the entrance to the Most Holy Place, to the Sanctuary. It is also possible that it was already Archbishop Absalon who moved them to their present places in connection with a reform of the cathedral, which he undertook in 1187. This would mean that the pictures were connected with a liturgy, which was then abandoned but at the same time, their expression value was so marked that they were allowed to do a new service in the church. It is perhaps no coincidence that they then got their place in the church hall, which apparently served as the Archbishop’s special chapel. Where these were originally found may be difficult to determine, but it is possible that they were intended for the interior of the church and marked the entrance to the Most Holy Place, to the Sanctuary. It is also possible that it was already Archbishop Absalon who moved them to their present places in connection with a reform of the cathedral, which he undertook in 1187. This would mean that the pictures were connected with a liturgy, which was then abandoned but at the same time, their expression value was so marked that they were allowed to do a new service in the church. It is perhaps no coincidence that they then got their place in the church hall, which apparently served as the Archbishop’s special chapel. It is also possible that it was already Archbishop Absalon who moved them to their present places in connection with a reform of the cathedral, which he undertook in 1187. This would mean that the pictures were connected with a liturgy, which was then abandoned but at the same time, their expression value was so marked that they were allowed to do a new service in the church. It is perhaps no coincidence that they then got their place in the church hall, which apparently served as the Archbishop’s special chapel. It is also possible that it was already Archbishop Absalon who moved them to their present places in connection with a reform of the cathedral, which he undertook in 1187. This would mean that the pictures were connected with a liturgy, which was then abandoned but at the same time, their expression value was so marked that they were allowed to do a new service in the church. It is perhaps no coincidence that they then got their place in the church hall, which apparently served as the Archbishop’s special chapel.

The understanding of the Romanesque sculpture of the church has been largely alive during most of the Middle Ages, probably not so much due to an aesthetic appreciation of it as a certain form of ability to identify the concepts it embodies. However, as recognition does not go away, the interest and care of the images also relax. Thus, already in the late Middle Ages, ornaments and sculptures, which have been in the way of necessary building alterations, should have been rendered useless. However, there could hardly have been any active destruction. One might imagine that, by analogy with what occurred in some parts of the continent, such devastation would have occurred through the Reformation. Fortunately, the cathedral was spared from here, but a multi-hundred-year maturity period met. However, neglect cannot be described as a destruction, but can almost be regarded as a result of the building’s changed function. From being the most prominent bishopric and rabbit church in the Nordic region in connection with the European church community, it was transformed, above all, into a parish church in a nation-state without overly lively contacts with European church life. In such circumstances, some parts of the church ceased to function, parts that were of prominent liturgical significance from the outset, depicted figuratively through sculpture. This, then, at best, received a curiosity value, as a deterrent from a superstitious time. From being the most prominent bishopric and rabbit church in the Nordic region in connection with the European church community, it was transformed, above all, into a parish church in a nation-state without overly lively contacts with European church life. In such circumstances, some parts of the church ceased to function, parts that were of prominent liturgical significance from the outset, depicted figuratively through sculpture. This, then, at best, received a curiosity value, as a deterrent from a superstitious time. From being the most prominent bishopric and rabbit church in the Nordic region in connection with the European church community, it was transformed, above all, into a parish church in a nation-state without overly lively contacts with European church life. In such circumstances, some parts of the church ceased to function, parts that were of prominent liturgical significance from the outset, depicted figuratively through sculpture. This, then, at best, received a curiosity value, as a deterrent from a superstitious time. picturized concretely through the sculpture. This, then, at best, received a curiosity value, as a deterrent from a superstitious time. picturized concretely through the sculpture. This, then, at best, received a curiosity value, as a deterrent from a superstitious time.

Since Skåne and Lund became Swedish in 1658, the city and the church came to be even more isolated from the outside world and towards the end of the 18th century, the unconscious came to take active expression. Some of the characters began to grieve and had a serious suggestion of the whole demise of the abyss. Fortunately, the huggeries were stopped and the demolition was prevented at the last moment. During the 19th century, the church underwent two major and very thorough restorations. They took place partly in the spirit of a newly awakened romantic mind for the me-part-time art. This did not in itself mean an understanding of its specific nature, but did contribute to an appreciation, which laid the foundation for further study. When the church today is newly restored,

In its Nordic environment, the cathedral sculpture fascinates the viewer. To a large extent, it is an alien bird here, but you soon discover how, due to a transformation during the coming decades around the middle of the 12th century, it contains a lot of universality but also hints of local origin. If you see the sculptures together, as you can see them in the pictures, you discover even more the rich shifts, and that something happens. It is not primarily a stylistic event, but a movement outside of time and space, a shaping of the inner tensions that created the image and conditioned its affinity with the building.

In reality, it is difficult to even be aware of the little relief with Adam and Eve, who sits in an arc field over the northern side ship tracks. But in this rendered image we see what happens. The summary “rocket dolls” tell themselves about the moment when they imposed themselves and us the human conditions. Eva eats from the fruit and gives Adam a bit of enthusiasm, which with a pat on the stomach seems to have already known the bitter sweet sweetness; or has he become aware of his nudity, which he tries to hide with his hand. Significantly, it is the apologetic and the woman accusing Adam of facing the spectator, while Eve turns away from him. Everything happens at once and in the same movements of two figures, who are not static but are in both rest and movement. Adam’s head and torso are fixed in his frontality, but with his legs he leaps. The figures do not move in a room or towards a target, they float, indeed almost swim in the background to which they are bound, and which constitute their sphere of existence in eternity. The depiction is universally valid by being naively alive and free from stylistically or tectonically normed conditions.

This independence and freedom from the principles of the external sense is an exception among the figure sculptures in the cathedral. From an architectural context, the plastic human image emerges. As Atlantans, the powerful figures in the south side ship serve as the bearer of the weight imposed by one of the arches of the vault. They replace the Corinthian chapter’s volutes, but they have overcome the abstract technological form through their formality and the level of activity that they express by supporting a lower wreath of acanthus leaves, the only remaining remnant of the ancient plant capital.

This sculpture still sits in its original place and still participates in the overall function for which it was initially intended. Unfortunately, this is not the case with the image of the faithful Christ and an archangel, which are kept in the cathedral museum. What place they and yet another but now lost archangel originally held in the church is not entirely known. The ignorance of this also complicates the immediate interpretation of the figures, not the interpretation of what they represent but of their significant function. The overall effect has been lost. But yet the figure of Christ is emerging as a plastic reality from the background of eternity. In the form of the incarnate God, the human image has detached itself from the superficial shadow world in which Adam and Eve lived, freed themselves from the tectonic coercion that conditioned the existence of the two Atlanteans in the lateral capitals, and took bodily form in order to elicit to the same extent the sacred figures that surrounded it. The existing color fragments give an indication of the luminous power that once emanated from the figure. Then the eyes have also been alive and granted the full activity of the form resting in the form, not the activity of the physical movement but the spiritual efficacy, boundless in the dimension of eternity from which the image also emerges as creation.

The same paradoxical union of spiritual movement and elevated rest characterizes the seraphim, who probably once surrounded Christ and the archangels. Through the covering wings, they possess an unity in themselves, an end unity that corresponds to their function in the heavenly dominion closest to the throne, only where ever present and praising but not as Christ and His archangels present and intervening in the world. We find not only a contrast in this solemn rest versus the flaming movement of pure spirituality, which the wings can sometimes convey, but also a paradox in the fact that these beings without contact with time and space seem to appear in more conspicuous plastic form than the embossed figures. This more or less circular sculptural character, however, has in the Romanesque sculpture a remarkable ability to isolate the figures, to let them not merely motion-semantically but also ideally become static in their own end unit. Not so with the relief image, which retrieves its formal and non-existent condition in the background of the active sphere of eternity, which is also conveyed to the spectator. In connection with the image of Christ and the archangel, the religiously tangible power from which the figures themselves rise, and of which they are a body, is perceived. But the background sphere can also be secretive and intangible, a residence of powers and potential forces, existing in themselves as well as in the spectator. A body of this can be found in the fee freeze at the northern decline of the crypt. Lions, dragons and snakes form in each other, they are transformed into alternating shapes as they encircle each other, emerge in uncontrollable movements from the dark background,

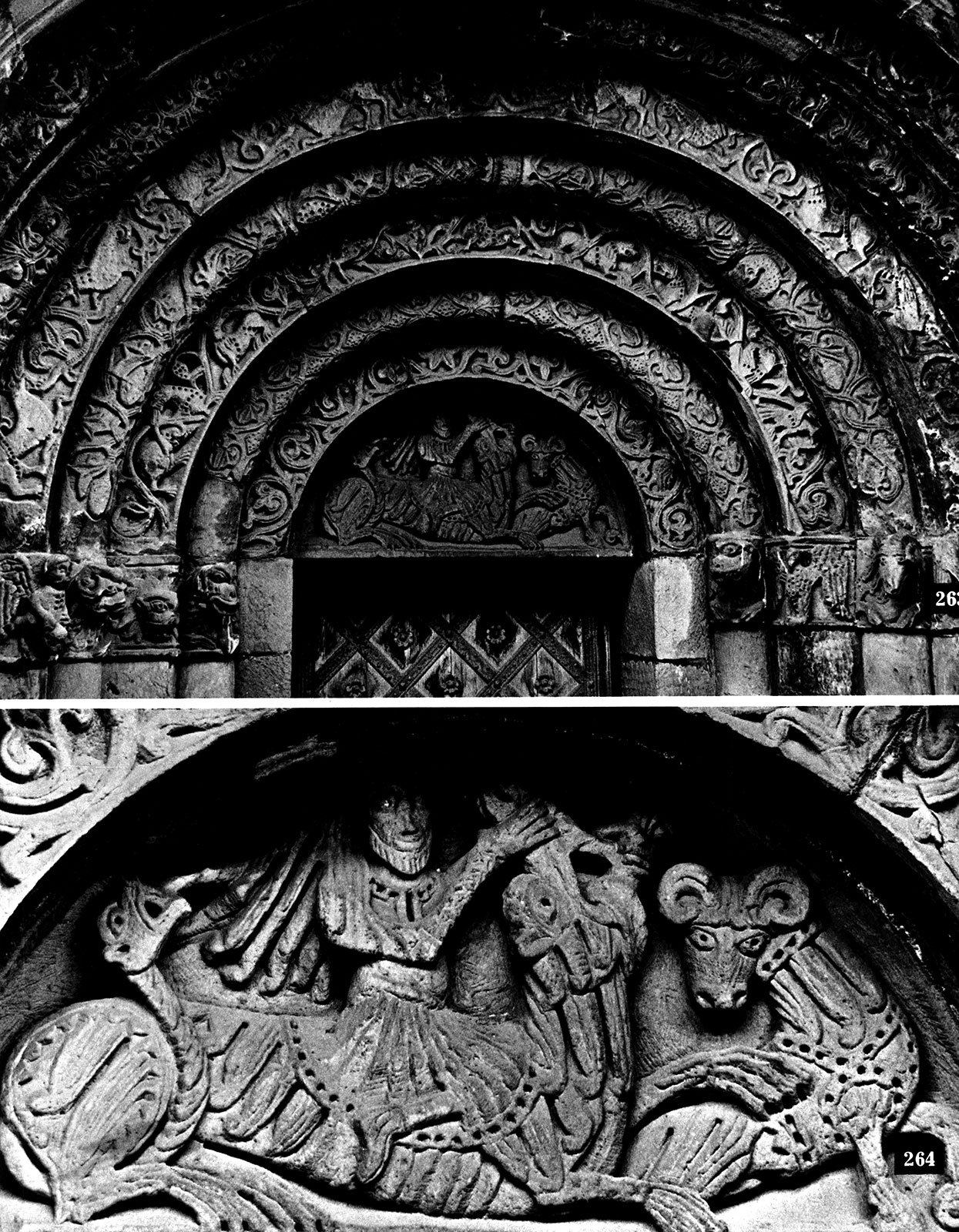

We do not know what is really meant by the magnificent sculptural ensemble that we find over the Northern Chapel, but a study of the relationship between the details of the images allows us to imagine an inner context. During the faithful cherub, man and animals have entered the world. The anxious human couple embrace each other in a timid but protective manner, and at their feet two lions watch as animal representatives. The small shapes have been given tangible plastic shapes in the room. They exist as tangible sculptural entities. They also exist in the world, but as the free Romanesque sculpture is closed in itself, the human couple and their animals are isolated in what is now their existence in the world. However, this instantaneous presence is not definitive. Above and around the free sculpture group, a bow with a wide relief border arches, in which the natural creation has gone towards its completion. In the artificially braided rank, from which lily palmettes, leaves and life-giving grape clusters are derived, are inserted and woven into a pattern four-footed animal, birds and a small man. They no longer represent the earthly figures whose image they borrowed but the blissful souls of heavenly paradise. The flat figures move in a breakthrough braid in which the rhythmic repetition of meeting and return of the loops gives the impression of constant life. The figures and plants do not appear to adhere to the dark background but rather to rest in it, but also to rise from it and extract its existence from the varying dark light, which transforms the tactile background into a sphere of spiritual dimension. leaves and life-giving grape clusters are removed, inserted and woven into a pattern of four-footed animals, birds and a small human being. They no longer represent the earthly figures whose image they borrowed but the blissful souls of heavenly paradise. The flat figures move in a breakthrough braid in which the rhythmic repetition of meeting and return of the loops gives the impression of constant life. The figures and plants do not appear to adhere to the dark background but rather to rest in it, but also to rise from it and extract its existence from the varying dark light, which transforms the tactile background into a sphere of spiritual dimension. leaves and life-giving grape clusters are removed, inserted and woven into a pattern of four-footed animals, birds and a small human being. They no longer represent the earthly figures whose image they borrowed but the blissful souls of heavenly paradise. The flat figures move in a breakthrough braid in which the rhythmic repetition of meeting and return of the loops gives the impression of constant life. The figures and plants do not appear to adhere to the dark background but rather to rest in it, but also to rise from it and extract its existence from the varying dark light, which transforms the tactile background into a sphere of spiritual dimension. whose image they lent without the blissful souls of heavenly paradise. The flat figures move in a breakthrough braid in which the rhythmic repetition of meeting and return of the loops gives the impression of constant life. The figures and plants do not appear to adhere to the dark background but rather to rest in it, but also to rise from it and extract its existence from the varying dark light, which transforms the tactile background into a sphere of spiritual dimension. whose image they lent without the blissful souls of heavenly paradise. The flat figures move in a breakthrough braid in which the rhythmic repetition of meeting and return of the loops gives the impression of constant life. The figures and plants do not appear to adhere to the dark background but rather to rest in it, but also to rise from it and extract its existence from the varying dark light, which transforms the tactile background into a sphere of spiritual dimension.

These images, like Christ and the angelic statues, were once found in close proximity to the central part of the church room, around and in front of the high altar. As some parts of the liturgy in this place have been a sacramental presence, the images have been symbolic representations of the forms of the transcendent existence. The representations around the inner core, which the altar formed, have been characterized by calmness and solemnity. If we move west into the church, the sculptural image world will not disappear, but it will have a different character. We have already seen how at the northern crypt the unique animal forms can be transformed into zoomorphic mixed figures of a purely imaginative nature. The mobility of these figures, as well as those of the side-ship capitals, is not calm and dignified, but dramatic and thrilling. This tendency is increased to the outer extent of the two side ship portals. The arch-ranks do not have the same calm rhythm as in the interior; creeks, leaves and animals move in waves or jerky movements, which cause the entire upper portal scope to simmer. The animals do not wander quietly among the grape clusters, but twist, rush towards each other or bite into the creeks. In this cruelty there can be no question of the same meaning as in the broad arc in the interior of the church. The completion, which is intended there, is certainly indicated in the portal archives, but it still prevails, and what we experience is precisely the efforts to reach the world, which must, however, exist as the basis for the image. The real and evil powers that try to stop man in this way have also taken a tangible shape in the demons of the collar band capital. Here the devil and his appendages are revealed in sculptural tangible form and in varying forms; the frog-like lions glare angrily at the one who is about to enter through the gate, or the man gets up around the furious head; The angels, who come riding on beasts, are not the angels of God but the devils. In the chapter that carries the portal opening surrounding the edicule, man himself is included in the fight with the beasts.

This infernal world, which stands between man and her realization of himself in the sphere of archivolts, is radically counteracted and finally defeated by the forces acting in the tympanon field’s representations. These concrete and more clear images are also the main motifs in the portals’ pictorial decoration. Symbolically, they both represent Christ, though in different forms and in different phases of the work of salvation, through which he leads man unscathed through the gate to eternal life. In the northern portal you can see Samson saving the lamb from the lion’s gap, but Samson as well as the story is merely a picture of Christ and his salvation work, already foreshadowed in the Old Testament. In the southern portal the New Testament speaks, and the Salvation Work is already completed. For those who would be rescued from the lion’s gap, Christ has sacrificed himself, and as the Lamb of God, Agnus Dei, he takes with the lifted cross rod as a sign of victory the central place in the arc. The surrounding evangelist symbols stand as proclaimers of the happenings but also as a testimony of the validity of the event over time and space.

Without presuming an intention or even an awareness of the sculptors who performed the reliefs, in these two tympanic images, as in the aforementioned reliefs, we can experience a correspondence between the sculptural form and its contents. The power and movement that the Samson image expressively wants to convey is not of a physical nature. With pristine nonchalance he effortlessly ties up the lion’s gap, and the fluttering hair braids contrast with the lion’s dormant position. Simson’s free-standing figure instead expresses the spiritual force against which the lamb seeks, and the lion’s animal-headed tail in vain goes to attack. In the tympanon of the southern portal, Agnus Dei and the Evangelist symbols are themselves at rest, but inscribed in the rounds formed by the all-encompassing vine-can; are the participants in and co-operative in the life-giving spiritual power and movement, which ultimately derives its origin from the meaning of the central image. Despite its character of symbolic Christ-making, the concrete image of Samson is a historical story in the biblical sense, taken from a given period of time. The markedly plastic shape of the figures, as we have seen in other contexts, emphasizes this image and significant isolation. An opposite tendency is evident in the second tympanum field, where the superficial relief as a pervasive mesh pattern exists through the background and in correspondence with it depicts a mystery image, sprung from reality, a presence of the supernatural, regardless of time or space. Despite its character of symbolic Christ-making, the concrete image of Samson is a historical story in the biblical sense, taken from a given period of time. The markedly plastic shape of the figures, as we have seen in other contexts, emphasizes this image and significant isolation. An opposite tendency is evident in the second tympanum field, where the superficial relief as a pervasive mesh pattern exists through the background and in correspondence with it depicts a mystery image, sprung from reality, a presence of the supernatural, regardless of time or space. Despite its character of symbolic Christ-making, the concrete image of Samson is a historical story in the biblical sense, taken from a given period of time. The markedly plastic shape of the figures, as we have seen in other contexts, emphasizes this image and significant isolation. An opposite tendency is evident in the second tympanum field, where the superficial relief as a pervasive mesh pattern exists through the background and in correspondence with it depicts a mystery image, sprung from reality, a presence of the supernatural, regardless of time or space. this image and significance isolation. An opposite tendency is evident in the second tympanum field, where the superficial relief as a pervasive mesh pattern exists through the background and in correspondence with it depicts a mystery image, sprung from reality, a presence of the supernatural, regardless of time or space. this image and significance isolation. An opposite tendency is evident in the second tympanum field, where the superficial relief as a pervasive mesh pattern exists through the background and in correspondence with it depicts a mystery image, sprung from reality, a presence of the supernatural, regardless of time or space.

The different levels of layering of the reliefs, which so effectively contribute to the significance of the Romanesque sculpture, are given a purely architectural expression in the exterior articulation of Lund’s cathedral. The high base, which encloses the inside crypt, belongs to the fixed wall body. But beyond this and from the pedestal rise in rising rhythm three arcades, which are constantly in a definite relationship with the underlying wall, while at the same time granting the architecture a gradual rise and liberation from matter. The lower floor arc consists of pilasters and semi-columns as carriers of double arches. Both joints are firmly closed to the underlying wall and, despite their release from the solid base, give an impression of load. From this weight, the following arcade floor has been liberated by the wall-bound pilasters being replaced by free columns between the chapters of which only a resiliently ascending arch. The partial liberation from the wall body, which occurred in this floor, becomes complete in the upper arcade gallery with its densely packed columns in a free space in front of the inner wall.

In this erection and liberation of purely architectural art but with a sculptural effect, the sculptures included in the chapters and collars of the arcades also participate. The function of the collar stone is to support and carry, which is also what the two goats do, which erect against each other and with the back-thrown heads with their horns seem to receive the pressure from the outgoing double arch. In the second floor’s chapters, people and on the hind legs do four-legged animals do the same service as tectonically bearing elements in the corner of the capitals. The architectural system inherited from ancient thinking, which has underpinned the entire rigorous structure, has also sculpturally left traces in such detail as the acanthus leaves on the lower part of the capitals and the chemistry and dental sectional decoration of the capitals’ cover plates;

Has this exquisite execution of architectural-sculptural articulation of a building part been of purely aesthetic significance? We have a hard time imagining that. The abyss encloses the site of the original high altar and thus manifests outwardly this central point around which the church is erected and from which it is justified. The altar is not just a supper table, it was also the tomb of Christ and above all the place of resurrection through the sacramental meaning of the Mass. One of the relics descended into the high altar of the crypt in 1123 was considered to be descended from the tomb of Christ; it is around this that the massive pedestal joins in to align with the arcades of the upper church and the actual high altar thereon, in the arcades;

In a symbolic sense, the abyss is also an imitation of the roundabout around the tomb of Christ in Jerusalem, Anastasis, the site of the original resurrection, whose memorial building as the bearer of significance conveyed the spiritual reality for which it was built. The aftermath in Lund is thus not a copy in our sense, but through tradition it may be the content of ideas that has been imitated; the artistic form, on the other hand, is genuine and created according to the special conditions of time and place. In the latter respect, it is no less remarkable that, on the outskirts of then-Christian Europe, the absurd added among its peers in southern countries stands as one of the most beautiful creations in terms of both shape quality and significant expressive power.

When the monumental stone sculpture made its entrance into Lund’s cathedral, there was no equivalent in this rural countryside to this continually inspired Romanesque visual art. What existed were the erected stones with their Viking-era visual world, easily carved portal scopes at some of the many wooden churches as well as possibly a single stone relief on the earliest stone churches. These latter reliefs, in their stylistic form, must still have been strongly inspired by the style pattern of the older tradition. The situation was radically changed through the advent of the Archbishop’s Church. A previously unknown monumental image and form world made its entry into the Nordic environment. Here, however, it did not develop along the lines it would have followed in its native environment but instead became an enriching incentive for sculptural activity, which spread across the landscape and even beyond its borders. In this process, other impulses co-existed with domestic traditions. Even within the framework of the cathedral, in some places it is possible to discern how this later in the form of, for example. complicated animal trails with typically Nordic animal head endings have enriched the borrowed forms towards new sculptural life.

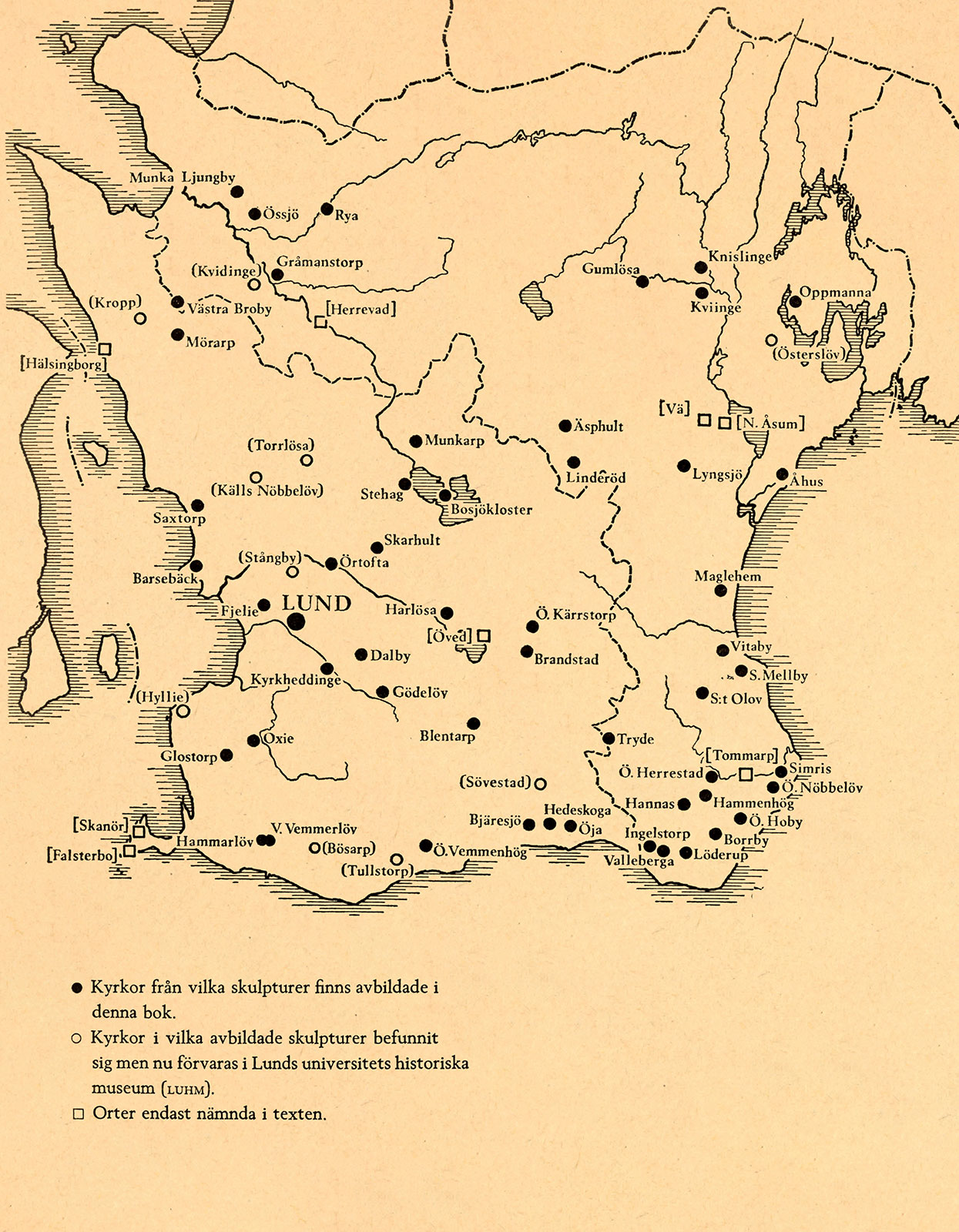

The influence of the Lundian sculpture on the countryside has, except in a few exceptional cases, not been direct. It has been pre-formation for the emergence of e.g. freely sculpted lion figures, but there are no slavish copies. The Lundian lion possesses something of a “naturalistic” suspense and pristine for its bearing function. From Tryde church is preserved a lion, who had the same function. It has, however, grown together with the base of the column it has carried, into a powerful block of sculptural action in itself.

Although the majority of rural Romanesque stone sculpture in its diversity and variety had no or little direct contact with the Lundian mold world, it is thus not said that the cathedral would not have any significance for its creation. The sculpture in the Skåne country churches would certainly not have exhibited such a multifaceted wealth, unless the cathedral existed as a stimulating factor, and as such it has played the greatest role for the Scanian visual arts in general.

At the cathedral building, sculptors have worked not only to acquire foreigners but, after all, with a high probability, also domestic labor. In this way, the building hut became a real melting pot for the rich sculptural development that the Skåne of the 1100s showed. We could imagine that such a Scanian master was responsible for the execution of, for example. the initiated but never completed relief found at the entrance to the Northern Transept Chapel. It may constitute the final vignette of this reasoning text. In the continuation of the figures, which you can imagine outside the picture area, is a hint of all the sculptures that exist, but which could not be accommodated within the framework of the book. The only contour sketch in the lower right corner gives an image of the character in this text. And in the two interconnected animals, which the Romanesque stone master never had the opportunity to complete, we see a reference to progressive creation, which was not only the task of the stone master but also ours, in which we, with activated consciousness again and with different aspects, experience the visual world that has been left to us from the century, which for Skåne has been in its spiritual sense richest and most vital.