The Bird, the Animal and the Human in Nordic Iron Age Art

Fuglen, dyret og mennesket i nordisk jernalderkunst

TEKST: BENTE MAGNUS

FOTO: GÉRARD FRANCESCHI

KOMPOSISJION: ASGER JORN

10000 ÅRS NORDISK FOLKEKUNST

BORGENS FORLAG

NORDISK JERNALDER BIND 2

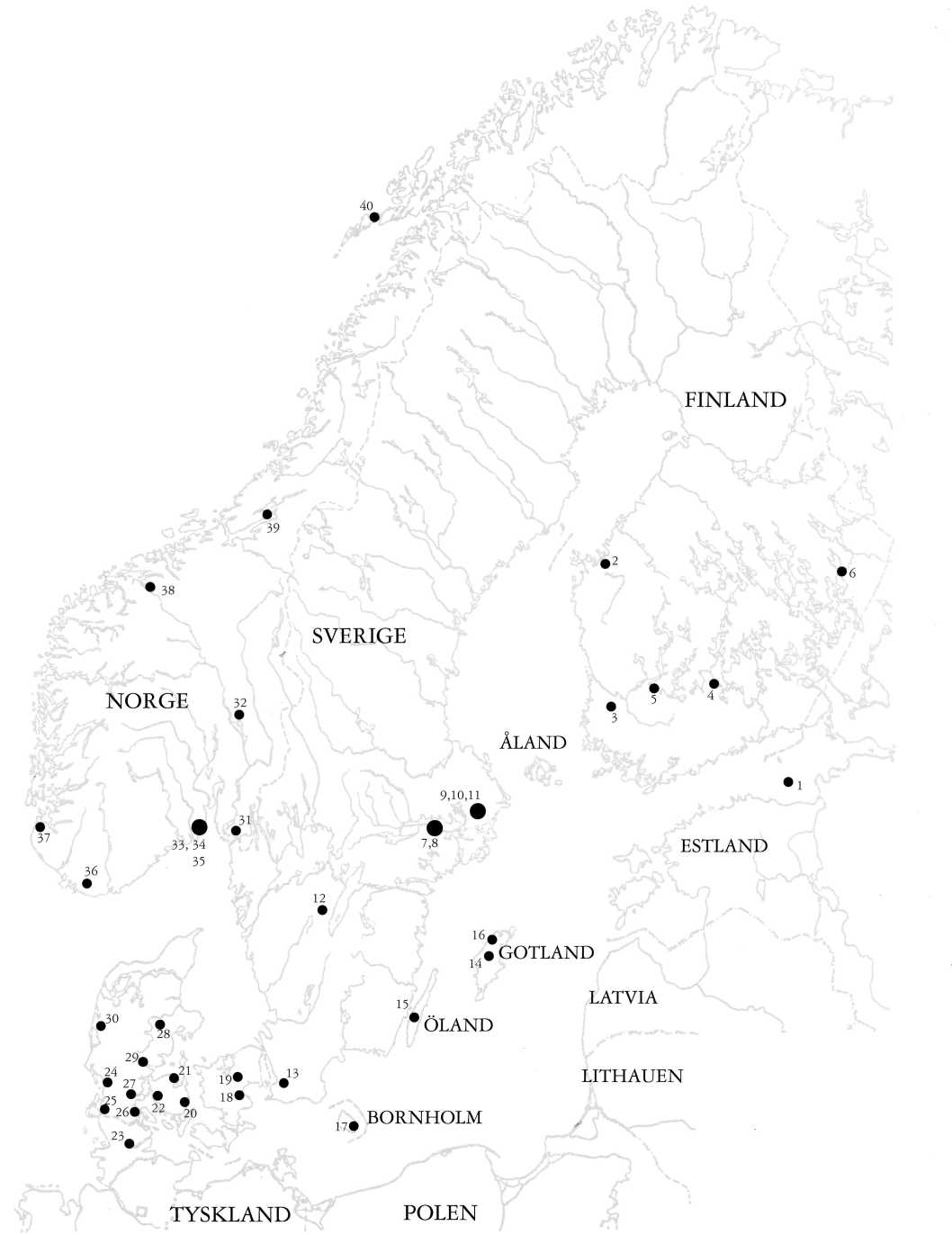

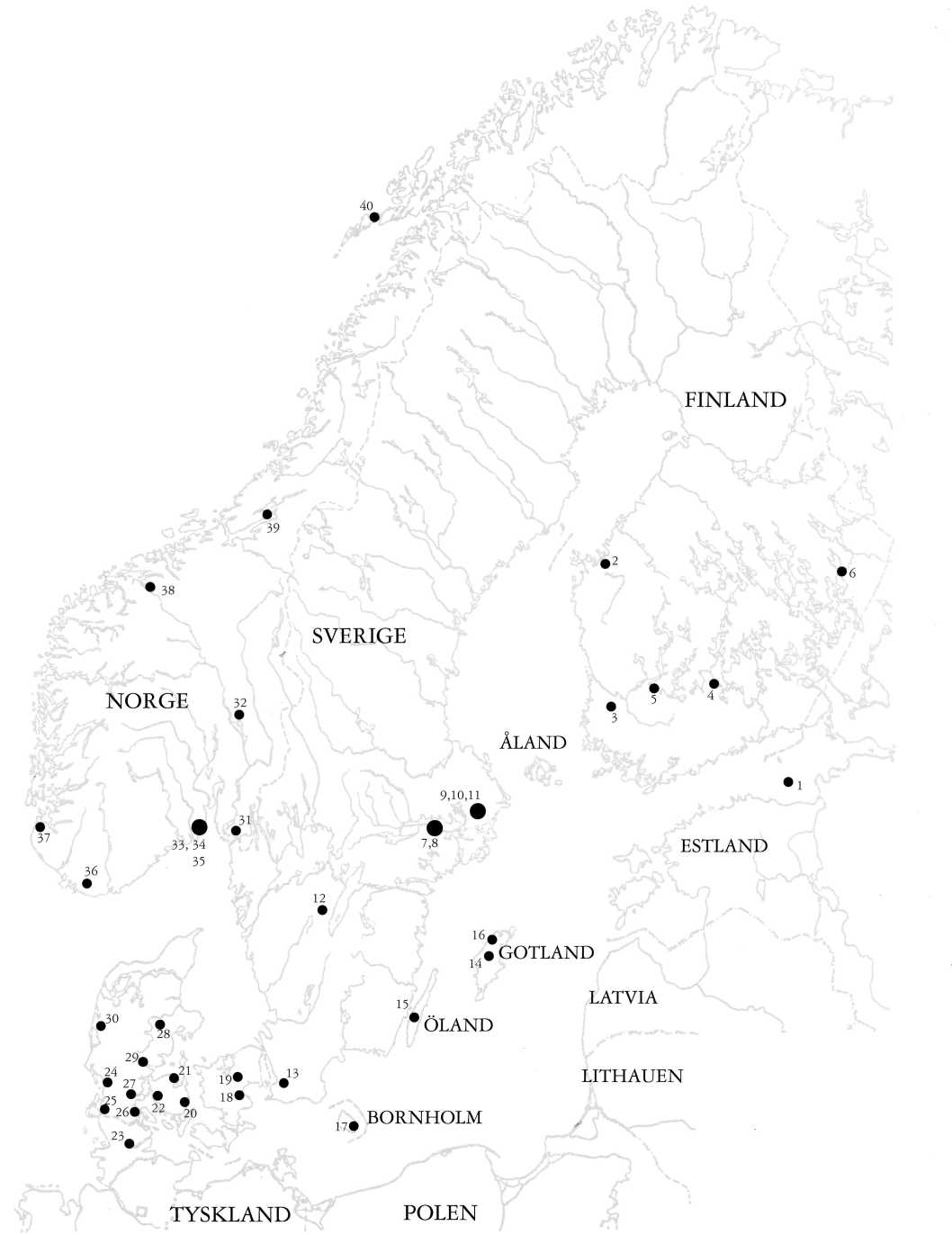

• Lokaliteter som ligger nær hverandre

Utvalgte lokalitetsnavn:

- Tytårsaari, Russland

- Gulldynt, Voyri

- Kjuloholm, Köyliö

- Papinsaari, Kuhmoinen

- Kirmukarmu, Vesilahti

- Joensuu, Halliko

- Helgo, Uppland

- Birka, Uppland

- Gamla Uppsala, Uppland

- Vendel, Uppland

- Valsgårde, Uppland

- Ålleberg, Västergötland

- Uppåkra, Skåne

- Kållunge, Gotland

- Torslunda, Oland

- Stora Ihre, Gotland

- Sorte Muld, Bornholm

- Himlingøje, Sjælland

- Lejre, Sjælland

- Gudme, Fyn

- Vimose, Fyn

- Søllested, Fyn

- Hedeby, Schleswig, Tyskland

- Ribe, Jylland

- Gallehus, Jylland

- Nydam, Jylland

- Ejsbøl, Jylland

- Mammen, Jylland

- Jelling, Jylland

- Dej bjerg, Jylland

- Tune, Østfold

- Åker, Hedmark

- Oseberg, Vestfold

- Borre, Vestfold

- Kaupang, Vestfold

- Snartemi, Vest-Agder

- Gausel, Stavanger

- Åk, Romsda

- Hol, Nord-Trøndelag

- Borg, Lofoten.

##FUGLEN, DYRET OG MENNESKET I NORDISK JERNALDERKUNST

Bente Magnus

Fuglen, dyret og mennesket

I sagnet om Sigurd Fåvnesbane finnes en berømt scene der Sigurd på oppfordring av smeden Regin steker den drepte ormen Fåvnes hjerte mens Regin tar seg en lur. Da Sigurd tar på hjertet for å kjenne om det er ferdigstekt, brenner han seg på fingeren og stikker den i munnen. Da forstår han plutselig hva fuglene som kvitrer i treet sier,- han forstår fuglenes språk, og får vite at Regin har planlagt å drepe ham.

Troen på at fuglene så alt og kunne forutsi menneskenes skjebne går tilbake til de eldste indiske skriftlige kildene og er et gjennomgående trekk i folkeeventyr. ”Hvis bare menneskene visste hva vi vet”, sier fuglene. Denne fuglenes kunnskap forsøkte både romere og germanere å skaffe seg via orakler. Tacitus forteller i sin bok om germanerne fra 98 e.Kr. (kapitel 10):”Også i Germania kjennes den meget utbredte skikk å søke varsler av fuglenes kvitring og flukt.” Hvilke fugler som ble ansett for å kunne gi orakelvarsler varierte. Men visse karakteristika var viktige sammen eller alene: Fuglens størrelse, dens farge(r), dens styrke, dens sjeldenhet, dens bevegelser, sangens/lydens variasjon og sangens styrke. Det spilte også stor rolle hvor lyden av fuglen kom fra, dvs om fuglen var skjult eller om den satt på en viktig bygning eller i et viktig tre lett synlig samt i hvilken himmelretning man først så den. En god del av dette henger fremdeles igjen som ”gammel overtro”, som f.eks. at de store uglene som kattugle og hubro varsler død, at det er viktig fra hvilken side man ser den første linerlen om våren og at gjøkens koko på forsommeren er forbundet med erotikk. Noen store fugler som sangsvaner og traner, og mindre fugler som viper, heilo og svaler kom årlig med lyset og våren til Norden. Når de dro igjen om høsten tok de med seg lyset og varmen og overlot menneskene til mørkets og kuldens krefter.

Visse dyr og fugler i jernalderen hadde menneskene et eget forhold til. Disse var gjenstand for beundring, respekt og frykt, og de utgjør hovedmotiver i kunsten. Den kristne forestillingen om at menneskene var dyrenes herre, ettersom Gud kun hadde skapt menneskene i sitt bilde, fantes ikke. Odin kunne skape seg om til hvilket dyr eller hvilken fugl han ønsket, og visse mennesker ble også ansett for å ha den evnen. På grunnlag av de norrøne sagaene og innskrifter på vikingtidens runestener vet vi hvilke ville dyr og fugler som i særlig grad ble brukt som mannsnavn i yngre jernalder,- Ulv, Bjørn, Orm, Hauk, Ørn, Ravn. I eldre jernalder, derimot, er de navnene vi kjenner fra runeinnskrifter dels dannet etter andre prinsipper. Her møter vi Lægæst, HagustaldaR, Wagnija og Nithijo, men også WiduhundaR som betyr skogshund og vel kan være en poetisk omskrivning for ulv, samt Stridsulv, Sverdulf og Hærulv som på bautastenene er skrevet HaÞuwulafR, HaeruwulafiR og HariwulafR. De teriofore navnene, dvs de som inneholder et dyrenavn, viser til hvilke dyr og fugler man mente hadde spesielle egenskaper som intelligens, styrke, utholdenhet, sluhet, klokskap. Med en dyrebetegnelse som fornavn mente man at dyrets eller fuglens egenskaper ble overført til mannen. Enkelte forskere har villet se de viktigste gudene bak denne typen mannsnavn fordi det åpenbart er en sammenheng mellom teriofore navn, germanske trosforestillinger og de dyr som er avbildet på gjenstander og billedstener. La oss se nærmere på disse dyre- / mannsnavnene.

Ravnen ble ansett for å være den beste orakelfuglen. Den er mest intelligent av alle fugler og kan tilpasse seg de mest ulike omgivelser og situasjoner. Dens svarte, glinsende fjærdrakt og mørke nebb skiller den ut fra andre kråkefugler. I Edda-kvadene omtales ravnen oftere enn noen annen fugl som likspiser på slagfeltet. Hvis ravnen blir tatt fra redet som liten er den lett å temme og kan læres opp til å artikulere ord. Germanernes viktigste guddom, Odin, hadde to ravner, Hugin og Munin, sinn og minne, som hver dag dro utover verden og hentet inn opplysninger til sin herre. Ravnene er således et bilde på Odins mentale evner. I Bibelens skapelsesberetning er ravnen den første fugl som Noah sender ut fra arken for å speide over jorden og gi Noah opplysninger om forholdene etter syndfloden.

Ørnen, den største av alle de nordiske rovfuglene var et symbol for Odin, og ett av hans navn var den ørnehodete. Ørnen svevet i stor høyde og med sitt skarpe syn hadde den oversikt over hva som skjedde langt nede under den akkurat som Odin når han satt i sitt høysete, Hlidskjalf, og så utover verden. Ørnen har kraftig nebb og store klør som gjør den i stand til å slå ned på et relativt stort bytte som lam og kidd. Ørnen er også evangelisten Johannes attributtdyr og var i det kristne romerriket, fra keiser Theodosius Is regjeringstid, et tegn på omvendelse til kristendommen.

De mindre rovfuglene ble kalt haukr (høk), og man hadde ingen spesiell betegnelse for falk. Begge var jaktfugler for aristokratiet i den nye jaktform som foregikk til hest og kom til Norden etter folkevandringstiden. Høk og falk er raske og dyktige jegere, og en jaktfalk kunne til og med ta opp kampen med en så stor fugl som en trane. I båtgravene fra Vendel og Valsgårde i Uppland fra yngre jernalder er flere av krigerne utstyrt med en hel oppsetning av rovfugler i tillegg til hunder og hest.

Ulven er lett, rask og smidig og jager i flokk. Dens hyl skaper frykt selv hos moderne mennesker. En ulveflokk som har nedlagt et stort bytte fråtser i kjøtt og blod til det nesten ikke finnes en hårdott tilbake. Guden Odin hadde to ulver, Freki og Geri, dvs den grådige. Disse lot han ete av de døde kroppene på slagfeltet. I sagaen om Egil Skallagrimsson fortelles i innledningen at Egils farfar het Ulv Bjalvesson. Om ham ble det sagt at han var en mektig mann og en god gårdsbestyrer. Han kunne gi gode råd om alt fordi han var en meget klok mann. Men når det led mot kvelden ble han folkesky, så det var få som kunne få ham i tale. Han ble søvnig; folk sa og at han var hamram, dvs. at han kunne skifte ham (skikkelse). Han ble kalt Kveldulv. Ettersom hans navn var Ulv, var det en ulvs skikkelse som hans frisjel antok mens kroppen tilsynelatende lå og sov om kvelden.

Bjørnen derimot, holder seg mest for seg selv unntagen en binne som har unger. Hos samene har bjørnen vært den fremste i dyreverden, og bjørnejakten har alltid vært sterkt ritualisert. Bjørnen opplevdes som et helt spesielt dyr. Den er sålegjenger, dvs går på hele foten som et menneske, den kan klatre i trær, reise seg og gå på to ben som et menneske og går i hi om høsten. Da forsvinner den, men med våren kommer den tilbake, og i tilfellet det er en hunbjørn har hun med seg en eller to unger. Men det som har ført til at bjørnen har hatt en slik fremskutt stilling i myter og senere folketro, er at en flådd bjørnkropp likner et menneskes og at selv skjelettet har likheter med et menneskes. Derfra er det ikke langt til forestillinger om at bjørnen er et omskapt menneske. Bjørnen har ti manns styrke og tolv manns vett, heter det i et gammelt ordtak, og fremstående kvinner og menn i jernalderen ble begravet eller kremert liggende på en bjørnefell med klørne bevart. Hodet, derimot, er aldri med.

Visse elitekrigere i yngre jernalder ble kalt berserkir og ulfhednar. Berserkr betyr enten bjørnekjortel eller brynjeløs, ulfhednir betyr kledt i ulveskinn. Trolig ved hjelp av noe slags rusmiddel forsatte krigerne seg i en ekstatisk tilstand av blindt raseri før en kamp og ble derved helt ufølsomme for smerte og fare. Denne kraften, sier Snorre Sturluson i Ynglingesagaen, fikk de fra Odin, hvis germanske navn Wotan betyr den rasende:” …hans egne menn gikk brynjeløse og var gale som hunder og ulver, de bet i skjoldene, var sterke som bjørner eller stuter; de drepte alle mennesker, og hverken ild eller jérn bet på dem. Det kalles berserkrgang.”

Ormen var en av Odins hjelpeånder og kunne sendes på oppdrag til underjorden. Den skifter skinn, forsvinner inn i hulninger i jorden og er borte om vinteren. I Snorre Sturlusons Skaldskaparmal forteller han myten om opphavet til diktekunsten. Jotnen Suttung hadde skaffet seg skaldemjøden som fantes i tre kar og satt sin datter Gunnlod til å vokte dem inne i fjellet. Odin lurte en annen jotun til å borre et hull i fjellveggen. Så skapte han seg om til en orm og krøp inn til Gunnlod, og ved hjelp av elskov stjal han mjøden fra henne. Derfor var han også skaldekunstens guddom.

Svin eller galte var det likevel ingen som het på tross av at villsvinet spilte en rolle i mytologien og som totemdyr. Det henger muligens sammen med at villsvinet forlengst var utryddet i hele Skandinavia i yngre jernalder, og at villsvinjakt derfor var noe som bare et fåtall nordiske menn hadde deltatt i kanskje hos frender i nåværende Baltikum eller Polen. Motivet, som ikke forekommer ofte i Skandinavia, kan derfor være overtatt fra kontinentale germanere.

Villsvinene er både sterke, raske og farlige i tillegg til at de får store kull unger og dermed blir symbol på fruktbarhet. Bortsett fra fenomenet svinefylking der krigerne stiller opp i V- form som et grisetryne og som knyttes til Odin, var villsvinet knyttet til vanegudene Frøya og Frøy. Frøya var både fruktbarhets- og dødsgudinne og delte de falne på slagmarken med Odin. I kvadet Hyndluljod fortelles at når Frøya ville skaffe sin yndling Ottar den enfoldige en forkledning, skapte hun ham om til et svin, Hildisvin, dvs. kampsvin. Da fikk han villsvinets styrke, raskhet og ureddhet. På krigerens hjelm i Vendel grav XIV er det fremstilt en prosesjon av krigere der én bærer en villsvinmaske med store huggtenner. I et depotfunn fra Öland med bronsematriser for fremstilling av billedblikk til hjelmer viser en av matrisene to hjelmbærende krigere med villsvin på hjelmkammen (Bind 1, 50-51). Guden Frøys svin het Gullinborsti og var skapt av dvergene. Det kunne fare over land og hav både i dagslys og i mørket for busten lyste som gull, noe som kanskje kan henge sammen med at villsvinene er nattdyr. I Odins Valhall fantes galten Særimner som vel må regnes som en vanlig gris. Den ble slaktet og kokt hver kveld, når Odin hadde vekket de falne krigerne til live igjen etter dagens kamptrening. Særimner var like hel dagen etter og kunne fortæres i all evighet. Odin hadde evnen til å vekke opp mennesker og dyr fra de døde. Gudinnen Frøya ble kalt syr, sugge, av visse skalder på 900-tallet, og Olav Haraldsson, den senere Olav den helliges stefar, Sigurd, som var småkonge på Ringerike, hadde tilnavnet Syr. Her er det også den vanlige domestiserte grisen som må være grunnlaget for tilnavnet. Om dette var så nedsettende som vi oppfatter det i dag, er uvisst.

Hesten var det eneste av de domestiserte dyrene som ble regnet for å stå mellom gudene og menneskene og som derfor hadde en helt egen status. Tacitus forteller: ”Men særegent for germanerne er at de også tar varsler og forutanelser fra hester. Hester av dette slaget ales opp på felles bekostning og holdes i de før nevnte hellige skoger og lunder; de er helt hvite og blir aldri vanhelliget ved å brukes til vanlig arbeid. De spennes for en hellig vogn, og stammens prest eller konge eller høvding følger dem og gir akt på hvordan de knegger og pruster. Og intet varsel blir mottatt med større tiltro, ikke bare av menigmann, men også av de høyættete og prestene. Prestene betrakter nemlig seg selv bare som gudenes tjenere, mens hestene etter deres mening er gudenes fortrolige.” At guden Balders hest snublet og skadet foten var f.eks. et varsel om Balders død. Hesteoffer var det mest sakrale av alle offer til guden Frøy, og offermåltidet på kokt hestekjøtt det aller viktigste. I folkevandringstiden ble det vanlig å gravlegge rytterkrigere, høvdinger og konger sammen med sine hester. Frankernes første konge, merovingeren Childeric, død 482 e.Kr. ble begravet i en enorm gravhaug i Tournai i Belgia. Minst 21 hester ble slaktet og begravet i tre store groper plassert omkring haugen. Tolv hester fikk sette livet til og følge Osebergdronningen på hennes siste ferd i sitt skip i Vestfold, Norge i 834 e. Kr. Hestene hadde mange roller i samfunnets toppsjikt, og de var et tegn på makt og rikdom. Deres rolle som orakeldyr som stod mellom guder og mennesker har sikkert spilt stor rolle når de ble drept og lagt i graven. Det hendte også at hestene fikk egne graver, og den tidligste som hittil er kjent i Norden ble funnet på et gravfelt fra 3. årh. i Udby på Sjælland. Odins hest, Sleipner, var en sjamansk skapning hvis navn betyr ”den glidende”, dvs den som går mellom verdnene. Den var grå, hadde åtte ben og på dens tenner var det innlagt runer.

Følge og frisjel

Etter norrøn sjeletro ble hvert menneske født med en slags skyggeskikkelse i form av et dyr, en fylgja, følge, som gikk foran hele livet. Den fungerte som menneskets alter ego, en ytre sjel som mennesket hadde i tillegg til kroppssjelen og som levde og døde sammen med mennesket sitt. Et menneske kunne se sin dyrefølge i drømme, og det var da et varsel om at han eller hun snart skulle dø. Så man derimot andre menneskers følge i drømme, var det et tegn på at noe kom til å hende. Det er trolig at forestillingene om følgen henger sammen med etterbyrden, men sammenhengen mellom denne og følgen i dyreskikkelse er uklar. Troen på at mennesket hadde en kropp som herberget en frisjel var grunnlaget for sjamanismen der Odin var den ypperste utøver. Ved hjelp av ekstase eller trance kunne en sjaman eller volve spalte kroppen og sjelen og sende sjelen ut på oppdrag for å løse et stort problem eller en krise. Kroppen lå da igjen som om den sov eller var død og sjelløs. Frisjelen ble forvandlet til et dyr eller en fugl, til sjamanens hjelpeånder. Odin forvandlet seg til de dyr og mennesker han hadde behov for i sin evige søken etter kunnskap, og som vist ovenfor, kan de mest vanlige mannsnavnene i yngre jernalder knyttes til Odin.

Dyr som motiv

Kunsten som skaptes i løpet av jernalderens siste 6-700 år gjorde bruk av motiver som nettopp henspiller på transformasjon/ forvandling fra menneske til dyr, fra dyr til menneske og Odins rolle som den fremste sjaman og største trollmann, men også som krigeraristokratiets fremste guddom. De få menneskefigurene som av og til synes mellom dyrefigurene forestiller sannsynligvis Odin selv eller noen av hans hjelpere. Karakteristisk for kunsten er at alle flater på de ornamenterte gjenstandene fylles av dyre- og fuglefigurer som sjelden går an å henføre til noen bestemt art. Typisk er det også at hver eneste avslutning på remmer, spenner, fibler og beslag avsluttes med en maske, et dyrehode eller et rovfuglhode. Kunststilene forandrer seg gjennom hele jernalderen fra omkring 450-1100 e.Kr. og kalles dyrestiler eller dyreornamentikk fordi firbente dyrefigurer sett i profil er hovedmotivet. Stilene er knyttet til samfunnets toppsjikt som bruker dem aktivt både politisk og som et ledd i en symbolsk og ideologisk kommunikasjon.

Egentlig inngår dyremotiv blant germanske hersker- og krigersymboler langt tidligere, men da med klar innflytelse fra provinsialromersk kunsthåndverk. På sølvbegrene fra en av de sjællandske Himlingøje-gravene fra første halvdel av 3. årh finnes f.eks. en frise i presset, forgylt sølvblikk under munningsranden (Bok 1, 11-13), jfr. tegning. Frisene er ikke helt identiske men inneholder det samme motivet, nemlig hukende, profilsette krigere som holder et romersk ringknappsverd. Krigerne har hjelm og synes å holde øye med en rekke dyr og fugler i et landskap. Scenene utspiller seg fra venstre mot høyre. Vi kjenner igjen en hest med innbøyde forben og en stor rund knopp under bakparten. Foran hesten står to mindre fugler som nærmest ser ut som ender, deretter en stor fugl med lang hals, krumt nebb og kraftige klør - den eneste som kikker bakover. På det ene begeret finnes dessuten to mannsmasker med lang bart. De er plassert slik at den ene virker som et speilbilde av den andre. Deretter følger en bukk eller gemse, nok en hest og en kriger. Den siste hesten (?) er fremstilt i profil med fire ben i motsetning til de øvrige som bare vises med to ben. Betyr det at den hadde åtte ben? Ingen av dyrene kan derimot klassifiseres som rovdyr, men den store fuglen kan være en stor rovfugl.

Her finnes en “tegneserie” som må vurderes i forhold til gravens øvrige innhold. Graven, der sølvbegrene inngikk som en viktig del, var en av flere som ble funnet ved grusgraving i 1828 og hvis sammenheng ikke er helt klar. I analogi med andre graver som inneholdt sølvbegre av samme type, var den gravlagte en mann, hvis øvrige gravutstyr bestod av romerske glass og bronsekar. Han har tilhørt det kongelige dynasti som i løpet av omtrent tre generasjoner frem til midten av 3 årh. behersket Sjælland, Fyn og kanskje Skåne. Selvom han ikke ble begravet med våpen, er det sannsynlig at han var både kriger og hærfører. Det er teoretisk mulig at han kan ha deltatt sammen med germanske frender i datidens store kriger mellom romere og germanere, markomannerkrigene i Bøhmen. Både sølvbegrenes friser og den store fingerringen med ravnehoder fra Himlingøje tyder på at det allerede omkring 250 e.Kr. har eksistert en ikonografisk sammenheng mellom visse dyr, visse fugler og krigere i det germanske samfunnets toppsjikt, men det kan ikke kalles dyrestil.

De som tapte kampen

De store våpenofferfunnene fra Nydam mose, Vimose, Illerup ådal og Ejsbøl mose illustrerer tilkomsten av dyreornamentikken mellom fra 3. årh. og ut 5. årh. Det var en tid preget av plyndring og strider. De som klarte å komme seg til makten gjorde dette ved hjelp av veltrenete krigere som de hadde i sitt brød og et stort nettverk av familie, slekt og mektige personer som var knyttet til dem ved giftermål, fosterskap og som gissler. Nettverket kunne strekke seg over store deler av det ikkeromerske Europa. Gull var en viktig ingrediens i det å skaffe seg makt og lojale tilhengere, og halsarm- og fingerringer av gull var viktige lojalitetsgaver. En romersk gullring med signet som forestiller guden Bonus eventus var naturligvis en statusmarkør på samme måte som ravnehoderingene, men viser til bærerens kontinentale kontakter. Tyngre, germanske gullringer kun med stempelornamentikk har vært helt essensielle i samfunn der den eksklusive gaven var et middel som småkonger og høvdinger benyttet for å knytte til seg andre mennesker, det være seg profesjonelle krigere eller alliansepartnere av alle slag. Våpenofferfunnene har vist at hærene allerede omkring år 200 e. Kr. var profesjonelt oppbygget. Hierarkiet fremgår tydelig av såvel bruken av edelmetaller som av antallet våpentyper og utstyr. Krigerne med sine ledere har vært samlet fra store områder, og et krigstog må ha vært nøye planlagt i lang tid på forhånd. Hver offiser ledet antagelig sin kontingent av krigere. Lederne var ryttere, kledt standsmessig i fargerike klær som viste deres rang og gjorde dem vel synlige under kampens gang. De bar praktsverd med romerske klinger, og det røde skjoldet hadde bule av sølv med forgylte detaljer og med beslag i form av mannsmasker av de samme edle metaller. Armringer og fingerringer var av gull, og hestene var utstyrt med seletøy av forgylt bronse. Dette var representanter for den skandinaviske eliten, og mer eller mindre likeartet var det germanske krigeraristokratiet utstyrt på kontinentet.

I år 375 brøt hunnerne, et mongolsk rytterfolk uventet inn i forholdet mellom romere og germanere ved sitt overfall på goterne som bodde ved Svartehavet. I de neste 75 år klarte hunnerne å tilskanse seg makt og herredømme over flere germanerfolk i Europa og nådde langt vestover. Sagnene om deres konge Atilla og hunnernes annerledes krigskultur ble til myter som levde videre i mange hundre år i germanske skaldekvad. Hunnernes påvirkning på germanernes trosforestillinger og ritualer, kunst og krigerkultur er lite kjent. De oppfattes som en parentes i Europas historie i folkevandringstiden og anses kun å ha tilført germanerne ørnen som symbol og bruken av blodrøde granater innfattet i gull. Men det er tankevekkende, at på den tiden de lider sitt endelige nederlag og ”raderes ut” av historien ved slaget ved Nedaoelven i år 454 skapes den første dyrestilen i Skandinavia.

Ejsbøl offermose ved Haderslev i Sønder-Jylland har vært et sakralt område gjennom de første 500 årene e.Kr. Hvor mange ganger det har foregått kamper mellom inntrengere og regionale hærstyrker i denne delen av Jylland vet vi ikke, men hittil har det store moseområdet vist seg å skjule våpen og utstyr fra flere offringer. Under utgravninger i mosen mellom 1955 og 1964 kom det for dagen utrustning fra en nedkjempet hærstyrke på omkring 200 mann fra ca. år 300 e.Kr. Våpen og utstyr var som vanlig i krigsbyttefunnene, hakket, vridd, bøyd og banket i stykker før det ble ofret til en guddom ved å kaste bitene ut i vannet. Sør for denne nedlegningen fant man en yngre konsentrasjon av eksklusive og spesielt utvalgte våpen. Tre sverd med støpte, timeglassformete grep og sverdskjeder med beslag av forgylt sølv, og dertil tre remspenner av forgylt sølv. Til disse fyrstelige utstyrte sverdsettene hører sannsynligvis minst åtte sverd til med enklere utstyr. Praktsverdene med sitt utstyr er nedlagt i tidlig folkevandringstid, i tidlig 5. årh. e.Kr. og er blant de seneste danske våpenofferfunnene. Ornamentikken på beltespennene med sine beslagplater viser en helt annen oppfatning av dyremotivet enn ravnehoderingen og sølvbegeret fra Himlingøje og den lille dyrespennen med hinden med halvmånehorn og hennes lille kalv. Borte er pressblikk og den forsiktige bruken av stempler; nå gjelder dypt relieff med skarpe rygger og bruk av niello for å fremheve visse detaljer. Alle tenkelige endestykker avsluttes med et dyrehode i profil eller en face. Øynene er sirkelrunde og står gjerne ut. På den relativt lille flaten som beltespennen fra Ejsbøl utgjør er det presset inn ikke mindre enn seks dyrehoder. Alle tomrom er utfylt, selv inne i kjeften på de profilsette dyrehodene ses et lite dyrehode. Hodene er plastiske, og det er tydelig at figurene forestiller dyr, nærmest fabeldyr. Selve beslagplaten er inndelt i geometriske felter fylt med spiralornamentikk i skarpt relieff, det som kalles karveskurdsornamentikk og som egentlig er en treskjærerteknikk. Den viser en tydelig arv fra provinsialromersk ornamentikk særlig slik den arter seg på beltespenner på provinsialromerske militærbelter fra samme tid. Rovfuglhodene på hekten og maljen er med sine skrå øyne og skarpe, krumme nebb noe helt annet enn ravnehoderingens rovfuglhoder. Men det finnes et slektskap, nemlig selve motivet.

Vi er inne i folkevandringstiden der rovdyret og rovfuglen utgjør hovedmotivene i kunsten. Mellom 400 og 450 opptar de stadig mer plass på store draktspenner, våpen og belteutstyr. I Sösdalstilen arbeider gullsmedene med en todimensjonell flatestil i sølv der forsiktig bruk av stempelornamentikk, veksling mellom forgylte og ikke-forgylte partier og ganske naturalistiske dyrehoder er karakteristisk. Flatene er i ro, og noe behov for å utnytte tomme flater foreligger ikke. Annerledes er det med Nydamstilen, oppkalt etter det første våpenofferfunnet fra Nydam mose ca. 6 km nordvest for Sønderborg. Også Nydamstilen finnes på sverdutstyr, beslag til praktbelter og bandolærer og relieffspenner, alt av sølv og støpt i former av brent leire. Flåten utnyttes til bristepunktet, og det dype relieffet lar lyset spille og skape skygger. Her finnes flere dyrefigurer, som gjerne klatrer på utsiden av spennene og rovfugler sett i profil samt ett og annet menneske. Men kvinnegravene viser at ikke bare høvdingen/hærlederen står sterkt i folkevandringstidens dyr-/menneskeforestillinger. Kvinnenes store draktspenner, relieffspennene, er eksempler på gullsmedenes ypperste kunstverk. Selv blant de tidlige smykkesettene finnes den gåtefulle dyreornamentikken.

Husfruen på Hol

Det begynte desverre med nok en versjon av den gamle historien: En bonde skulle fjerne en ”steinrøys” som lå ved låvebroen og kom raskt ned på en gravkiste av store heller, 4 m lang og 80 cm bred. Den var fylt med jord og ble godt gjennomrotet. Derved fant man et antall gjenstander som tilhørte en av de mest spennende kvinnegraver fra tidlig folkevandringstid fra Midt - Norge. Kvinnen var blitt utstyrt med skrin, leirkar og tekstilredskaper og var stedt til hvile i en drakt som krevde flere fibler av sølv. Den har vært holdt sammen i livet av et 2 cm bredt lærbelte med beltering av bronse. Ringen er omgitt av fem hester i gjennombrutt arbeid og selve rembeslaget har form som en mannsmaske. I beltet hang hennes nøkler i en nøkkelring og to kniver hvorav en med sølvholk. Blant hennes mange mindre draktspenner finnes to S-formete av forgylt sølv med profilsette dyrehoder. En unik, nærmest likearmet bøylespenne av forgylt sølv som avsluttes med et dyrehode en face i hver ende, har kanskje sittet lavt på brystet og gitt peploskjolen en rynkeeffekt. Bøylen mellom spennens to deler har både stempelornamentikk og en klassisk meanderbord i dypt relieff. På begge sider av bøylen finnes ett sett rovfuglhoder med sterkt krumme nebb, derunder et menneskehode i profil og en arm med en hånd og sprikende tommel og derunder et dyrehode i profil med lang, ormeaktig kropp. Det finnes en usynlig midtlinje gjennom hele spennen fra den ene spissen til den andre, og motivene er omtrent de samme på begge sider av denne midtlinjen.

Motivet med en menneskefigur mellom rovdyr går igjen på den store relieffspennen, også den av forgylt sølv og helt unik. Hodeplaten har sølvknopper som er satt fast på en liten list av sølv. Ornamentikken består av en rekke havhestliknende dyr med stripet kropp og et spisst hode med runde øyne som kikker bakover. Innenfor disse finnes en rad firsidige felter med firkantete knotter og deretter et spiralornament, begge i dypt relieff. Selve spennefoten er vinklet som et tak (takfotspenne) og har øverst det samme spiralornamentet som på spennens overdel. Men det interessante er bildene som er tegnet naturalistisk. På høyre halvdel ses øverst en sammenkrøpet (eller hukende) menneskefigur, en mann i profil med armen bøyd og 55 og hånden med sprikende tommel foran ansiktet. Han er tegnet med stempler og er barhodet. Klesdrakten består av bukser og tunika med belte. Under ham finnes et profilsett dyr med kort, bredt hode og åpen kjeft. Dyret synes å gripe tak i mannen med bena. Bak ryggen på dyret kryper nok et profilsett dyr. På venstre halvdel kryper tre dyrefigurer; den øverste med smalt, langt hode som synes å bite etter et kort, kraftig dyr med åpen kjeft og skarpe tenner. Nedenfor ligger et dyr med hodet opp mot midtdyrets rygg og en kropp som er ormeaktig men 56 med bakben. Dyrene er tydelig karakterisen og skal åpenbart forestille forskjellige figurer i et slags drama der den hukende mannen spiller hovedrollen. På den likearmete spennen fantes to menneskefigurer med hånden opp og sprikende tommel omgitt av rovfugler og ville dyr. Hva forestiller bildene? Mest sannsynlig handler det om guden Odin, og kanskje i en sammenheng der han slåss mot og overvinner dødsrikenes demoner.

Holkvinnens spenneoppsetning samt nøkler og veveredskaper viser at hun har vært en husfrue, en kvinne med makt og myndighet innenfor gården. Slike mektige kvinner har det, etter gravfunnene å dømme, vært mange av langs den lange norskekysten fra Vestfold til Nord-Trøndelag i folkevandringstiden. Deres nøkler symboliserer deres ansvar for husholdet og tekstilredskapene ansvaret for produksjonen av tekstiler og klær til alle. Men også skjebnegudinnene, nornene, vevet menneskenes liv fra fødsel til død slik at livsmønstret var klarlagt når barnet ble født. Sammen med spennenes ornamentikk som kretser om Odin og hans roller som sjaman, antyder tekstilredskapene at kvinnene hadde spesielle egenskaper til å ”se” inn i fremtiden og har dermed spilt en vesentlig rolle i ritualene knyttet til seid. Denne egenskapen påpeker allerede Tacitus (kap.8 i Germania) at germanske kvinner hadde. Derfor ble de rådspurt, og mennene ga akt på rådene. Flere kjente romere knyttet til seg en germansk seerske, en sibylle. I Ynglingasagaens kapitel 7 skriver Snorre Sturluson: ”Odin behersket den kunst som det følger den største makt med, og han utøvet den selv, det er seid. Derfor kunne han vite folks skjebne, og det som ennå ikke hadde hendt, han kunne gi folk død eller ulykke eller vanhelse, han kunne ta vett eller kraft fra folk, og han kunne gi det til andre. Men denne trollskapen følger det så mye umandig med, at mannfolk ikke kan drive med den uten skam, og derfor lærte de gydjene den.” En gydje var en kvinnelig kultleder.

Dyrestil

Omtrent halweis gjennom 5. årh. skapes i Syd-Skandinavia en egen kunststil der dyrefigurer står i sentrum. Den får sitt sterkeste uttrykk på de store relieffspennene av forgylt sølv eller bronse som ble båret av spesielle høyættete kvinner med viktige roller som husfrue og kultleder. Dyreornamentikken på disse praktspennene som er det ypperste som folkevandringstidens gullsmeder produserte, fikk også stor betydning for germanske folk i Europa i deres søken etter identitet og fast forankring i en ny verden etter vestromerrikets fall i 476. Denne første dyrestilen kalles Stil I og har vært viktig for hele Skandinavias bondebefolkning. Den mistet sin betydning først omkring midten av 6. årh. Nydamstilen, dens forgjenger, er bl.a. karakterisisert ved border bygget på klassiske motiver slik som spiraler i forskjellige sammensetninger, meandere og eggstaver. Dyr og menneskefigurer er fremstilt sammenhengende og i stor grad naturalistiske. I Nydamstilen er hver gjenstand nærmest unik, og stilen synes å ha hørt til i samfunnets toppsjikt. I Stil I løses figurene opp ved at deres enkelte deler fremheves med konturer. Hver del lever sitt eget liv og anvendes ofte uten noen sammenheng med resten. Det naturalistiske erstattes av forkortninger, stilisering og abstraksjon. Ikke uten rett er Stil I sammenliknet med kubistene og Picassos kunst. Stil I brøt tvert med romerske prinsipper for ornamental kunst, nemlig en naturalistisk fremstilling av motivene.

Mesterverk

På Galsted-spennen finnes fremdeles det klassiske motivet med et menneske mellom to dyr i bakgrunnen. Men dyrene har ingen rot i virkeligheten,- de er symboler. Hvert lem er omgitt av en dobbelt kontur, kroppen er et bredt bånd og hodet er forenklet ved at øyenbrynsbuen er forstørret og forlenget. Hva forestiller de to knelende dyrefigurene med den åpne kjeften som synes å sluke mannshodet? Siden de står på kne, er det mest sannsynlig at de er mannens tjenere, og at deres åpne kjefter heller antyder at de forteller ham noe enn at de er i ferd med å sluke ham. Mannshodet har stirrende, utstående øyne og halvåpen munn. Sannsynligvis er dette en fremstilling av guden Odin i trance omgitt av to av sine hjelpeånder som hvisker ham det de har sett på sin ferd dit de ble sendt. Galstedspennen ble funnet i en mose sammen med en gullbrakteat som viser en mann i ekstatisk bevegelse. Motivet tolkes som Odin i trance i kamp med demoner.

Relieffspennen fra Gummersmark på Sjælland er også et mosefunn der 8 gullbrakteater og 10 perler inngår. Spennen er av sølv og formmessig er den en typisk planfotspenne inndelt i tre deler - hodeplate, bøyle og fot. Dens ornamentikk inneholder alle trekk i den tidlige dyrestilen. En relativ høy og bred list med siksakmønster i niello deler fotens bilder i en indre og en ytre sone. Listen overgår øverst i to profilsette dyrehoder med spisse ører, spissovale øyne og åpen kjeft. Nederst avsluttes listen i en dyremaske med utstående, runde øyne og store, runde nesebor. Det indre billedfeltet er oppbygd med horisontale felter. Øverst finnes en liten figur med store runde øyne og en utbrettet kropp. Feltet under inneholder en sammenkrøpet menneskefigur med hjelm og hendene knyttet bakpå ryggen. Neste felt viser to dyremasker en face. De spisse ørene 35 ligger utenfor listen og mellom dem finnes en sirkelrund figur lik et stort øye. Maskene har skrå øyne og tydelige nesebor under to tverrstreker. Tvers over maskene løper en list med siksakbord. Rett under maskene ses en rovfugl sett ovenfra. Kroppen er brettet ut og bena ligger langs siden. Halefjærene er markert med loddrette lister. På utsiden av listen nederst på hver side av masken finnes en profilsett dyrefigur med spisse ører og lang, opprullet tunge. Øverst på foten på hver side av bøylen finnes en nokså naturalistisk dyrefigur, nærmest lik en hund.

Spennens hodeplate er rektangulær og har en krans av geometriske figurer ytterst. Figurene - en likebent trekant med en sirkel på toppen, finnes også på andre relieffspenner samt på vestnorsk, asbestblandet keramikk fra denne tiden og på goterkongen Theoderiks mausoleum i Ravenna, Italia. Det er altså et utbredt symbol, men hva betyr det? Mellom trekantene i hvert hjørne ses en maske og midt på langsiden en stor mannsmaske som viser en åpen munn med mange tenner. Snur man spennen, blir masken til en dyremaske og hører sammen med den utbrettete dyrefiguren uten hode som ligger i feltet nedenfor delt i to ved en bred list. Det utbrettete dyret blir igjen til en stor maske med skrå øyne og en åpen, leende munn. På hver side nederst på hodeplaten finnes et rektangulært felt med to menneskefigurer. Begge har hjelm og blikket vendt opp. De bærer tunika med bred bord nederst, og den høyre figurens benstilling synes å antyde at han utfører en slags dans. Slektskapet med de senere gullgubbene er åpenbar. Relieffspennen fra Gummersmark er et mesterverk som må være nedlagt i mosen sammen med et collier av gullbrakteater og glassperler som en votivgave til en guddom. Det er igjen den mektige husfruen vi aner, og hennes spesielle smykker som viser til hennes rolle som leder av kultiske handlinger. De vestnorske kvinnene av hennes dignitet ble begravet med sine “insignier”, men ellers i Skandinavia ble de åpenbart nedlagt som votivgave ofte i en mose, kanskje i forbindelse med kvinnens død.

Gummersmarkspennens motiver viser til myter som er tapt for oss. Men de synes å handle om guden Odin og hans evne til forvandling. Noe som ser ut som en mannsmaske, blir til en dyremaske og en del av et stort, utbrettet dyr. I Ynglingasagaen sier Snorre dette om Odin: ”Odin skiftet ofte ham [skikkelse]; da lå kroppen som død eller sovende, men selv var han fugl eller firbent dyr, fisk eller orm og for på et øyeblikk til fjerne land, i ærend for seg selv og for andre…” Odin var den største sjaman og trollmann og kunne overskride alle grenser: mellom levende og døde, mellom mann og kvinne, mellom dyr og menneske.

Dyre- eller menneskemasker, rovfugler og dyrefigurer er hovedmotivene på relieffspennene. Et annet karakteristisk trekk er at fremstillingen er delt, dvs at en midtakse deler relieffspennenes ornamentikk i to symmetriske deler slik at billedflaten blir brettet ut. Men det finnes alltid elementer av asymmetri som har en betydning, som f.eks. de to krigerne på Gummersmarkspennen. Holder man over halvdelen av en maske en face som alltid er delt med en lang neserygg, blir hver halvdel et dyr- eller rovfuglhode i profil. Alt er som det ser ut til og samtidig er det noe annet.

Det gåtefulle ved relieffspennenes ornamentikk blir enda mer akksentuert senere i folkevandringstiden. Figurene blir mer oppløste, og ofte representerer et lem eller et hode en hel figur. Det finnes menneskeheder med dyrekropp og vise versa. Selve budskapet som ligger i spennenes ikonografi blir sterkere kodet, og det er vanskelig å finne frem til et samlet motiv. Men det har vært viktig å vise øyne. De finnes overalt og må ha med seende å gjøre - visse kvinners evne til ”å se” inn i fremtiden. På den store relieffspennen fra Lundbjers i Lummelunda på Gotland finnes det 42, 43, 47 en maske som avslutter foten og en maske på hver side av bøylen. De har skrå, farlige øyne. Rovfuglhoder med skarpe nebb og skrå øyne ligger etter hverandre langs ytterkanten og inne i det 45 trekantete innerfeltet der en trekantet, rød granat utgjør midtpunktet. Granater finnes også på hodeplaten som noe slags hvile 44 for blikket i en ellers helt uforståelig ornamentikk.

Relieffspennen fra Overnhornbæk er et mosefunn som også 48 inneholdt gullbrakteater og glassperler. Spennen er ødelagt før den ble nedlagt i mosen ved at nedre del av foten med den avsluttende masken er brukket av. Masken kan ha fungert som amulett i andre sammenhenger. Dyrefigurene rundt hodeplaten er gjennombrutte og båndformete, og de to firkantete prydknappene er omgitt av hver sin spiralranke. En liknende ranke finnes på sverdhjaltet fra Snartemo i Vest-Agder, der knappen er voktet av to dyrefigurer i rundskulptur med rovfuglnebb. Snartemosverdet er et av de få gravfunne praktsverd som kjennes fra Skandinavias folkevandringstid. I mosenes våpenoffer er de derimot tallrike. Et slikt sverd gikk ofte i arv, og mange har hatt navn. De var utstyrt med ornamentikk og figurscener i Stil I men ikke av den gåtefulle sorten som kvinnenes relieffspenner.

De store relieffspennene er mesterverk av metallhåndverk i forgylt sølv eller bronse. Kunstnerne som skapte spennene var trollmenn og deres verk fylt av magi. Det kultiske aspekt av relieffspennene forsterkes ved at enkelte har en runeinnskrift på baksiden, og på en av dem står: Jeg Vi risser inn runer for Vivja, kjæresten. Vi eller ve betyr et hellig sted, et sted der spesielt utvalgte mennesker fikk kontakt med gudene og der forfulgte kunne finne beskyttelse.

En ny tid

Omkring miden av 6. årh. endrer kunsten så sterkt karakter at det må henge sammen med dyptgående endringer i samfunnet. Den kryptiske og hemmelighetsfulle Stil I fyller åpenbart ingen funksjon lenger i Skandinavia; de storstilte offernedleggelsene i mosene av krigsbytte og gull samt de mektige kvinnenes relieffspenner og gullbrakteater opphører. Gårder og gravfelt fraflyttes i Nordens randområder, og tyngdepunktet i Skandinavia flytter seg fra Nordsjøen mot Østersjøen. Blant de mange germanske stammene som gikk sammen i større enheter på kontinentet fylte den første germanske dyrestilen, Stil I, fremdeles og i lang tid fremover en viktig funksjon i en kaotisk og usikker tid. Blant angelsaksere i England, hos langobarder, gotere, gepider, alemannere var deres nydannete kongeriker truet av de frankiske merovingernes utvidelse av sitt territorium. For selvom de fleste av de kontinentale germanerne var blitt kristne, hadde kongeslektene et behov for å skaffe seg legitimitet og en historie som etablerte forbindelsen til en fjern fortid. Litt etter litt hadde de frankiske merovingerne innlemmet burgundernes, allemannernes, thyringernes, bayernes, rhinfrankernes og delvis saksernes kongerike i frankerriket. Av de selvstendige germanske kongerikene som oppstod etter vestromerrikets fall fantes omkring år 600 bare vestgoternes i Syd-Frankrike og på den iberiske halvøy og langobardernes i Nord- og Midt- Italia. Samtidig ekspanderte det bysantiske keiserdømmet fra Lille-Asia over Balkan til deler av Italia og Spania. Avarer og slaver utvidet sine områder ved Donau og nordvestover mot Østersjøen.

En ny ornamentikk oppstår bygget på dyr og rovfugler som motiver og med båndfletning som sammenbindende prinsipp. Stilen kalles Stil II og anvendes fra midten av 6 til slutten av 8 årh. over hele det germanske Europa, men minst hos frankerne. Samtidig er de merovingiske frankerne de ledende i Europa. Deres konge Klodvig går ca. år 500 over til den katolske kristendommen og ikke til arianismen som de fleste andre germanerne, noe som senere skulle vise seg å være et klokt valg i forhold til pavestolen i Roma. Flere tusen krigere i Klodvigs hird lot seg døpe. De store hærene bestod av menn fra mange forskjellige stammer, også fra skandinaviske. De hadde felles livsstil på grunnlag av en felles ideologi der heltedyrkelse og krigerens rolle og liv etter døden spilte en sentral rolle. Forestillingene om Odins Valhall ble erstattet med en kristen ideologi når krigerne ble døpt. Merovingerne og andre kongelige slekter synes å ha begravet sine medlemmer med full personlig utrustning i nyoppførte kirker. Adelen fulgte etter og utstyrte sine graver i store trekister eller kammere av tre med smykker av edelmetaller, fullt oppsett av våpen, hesteutstyr og bordserviser med glasspokaler og rikt utsmykkete drikkehorn. Dette på tross av at de var kristne. Det arkeologiske materialet fra merovingertidens Europa er svært rikholdig på grunn av gravskikken, og inneholder gjenstander ornert i Stil II. Påvirkningen fra det merovingiske riket på alle germanske kongedømmer og småkongedømmer i Skandinavia har vært sterk.

Det rådet lenge usikkerhet om hvor den nye kunststilen oppstod og hvordan den spredte seg så raskt. Langobarderne i Italia fikk lenge æren av å ha skapt Stil II som en utvikling av folkevandringstidens dyrestil og middelhavsområdets båndfletningsmotiver. Men etterhvert er man kommet frem til at stilskiftet må være skjedd først i Skandinavia, enten i Danmark eller i det svenske Målarområdet. Begge regioner hadde både politiske, religiøse og økonomiske forutsetninger og sterke kongeslekter med kontakter til både det frankiske og det angelsaksiske.

På grunnlag av det arkeologiske materialet synes det å ha utkrystallisert seg tre tidlige nordiske riker i denne tiden, som på dansk kalles yngre germansk jernalder, på svensk vendeltid og i Norge og Finland merovingertid, nemlig Danmark med Skåne, Småland, Oland og Blekinge, Målarområdet med sentrum i Gamla Uppsala og Gotland. Områdene er å oppfatte som tidlige kongedømmer, der militære operasjoner under sterke ledere stadig forandret deres størrelse. Folkevandringstidens mange stammebaserte høvdingdømmer ble i løpet av folkevandringstiden og den tidlige delen av merovingertiden erstattet av større territorier med godser der produksjonen av fødevarer, jern, tekstiler etc. var basert på overskudd. Kongene hadde sine edssvorne “bestyrere” som tok seg av tributtinnsamling etc. i hver region. Jordbruket ble lagt om fra en ekstensiv utnyttelse av marken til en intensiv med sterkere bruk av gjødsel. Det som kan kalles utmarksområder ble utnyttet i stadig sterkere grad. At omleggingen har vært preget av vold, er det ingen tvil om. Krigerelitens medlemmer var de reelle makthaverne. Allerede omkring 520 finnes det skriftlige opplysninger om at danenes konge Hygelak overfalt frankerne ved Rhinmunningen, og om herulenes vandring fra Jylland til Gotaland. Daner og svear var ingen stammebetegnelser i denne tiden men betegnelser på sammenslutninger av flere gamle stammer under én herskerslekt av svear eller daner. Kampen om ressurser og territorier har vært brutal og langvarig over hele det europeiske kontinentet, og de nye makthaverne har demonstrert sin makt med bl.a den nye dyrestilen på våpen og kvinnesmykker. Under bysantinsk påvirkning hadde frankerne gjort verotterie cloisonné med blodrøde, spaltete granater i gullceller med vaflet bunn til en eksklusiv kunst som raskt spredte seg i Norden. Sverdknapper, draktspenner, beslag og detaljer på remspenner var gjenstander som ble prydet med cloisonné i intrikate mønstre. Det var dessuten begrensete mengder av gull i omløp, og derfor fikk gaver av gull med granater stor symbolsk betydning i herskernes evige kamp for å beholde makten over ressurser og mennesker.

Krigeraristokratiet

Det nye samfunnet kan betegnes som krigersk i motsetning til århundrene tidligere der den militære organisasjon var basert på de ulike stammene. Det krigerske samfunn var basert på en hird der lederen hadde nærmest uinnskrenket makt og der våpenutstyret ble masseprodusert og var likt på kontinentet og i Skandinavia. Et krigersk samfunn var kanskje ikke mer voldelig enn tidligere, men det var så velorganisert og velutstyrt militært sett, at det ikke uten videre ble angrepet.

Gravskikken i Norden var gjennomgående basert på kremasjon av den døde der ilden har fortært det meste, og antallet graver fra 7. årh. i Norden er relativt lavt. Mengden av løsfunn fra merovingertiden har derimot økt lavineartet etter at metalldetektorene kom inn i bildet, og de mange smykkegjenstandene som er funnet gir bl.a. et bilde av hvordan dyreornamentikken ble brukt. På Bornholm gir rikt utstyrte våpengraver i kammer med hest etter frankisk innflytelse et bilde av den nye eliten. Men vil vi vite hvordan den frankisk pregete skandinaviske krigereliten tok seg ut i datidens Norden, er det de uppsvenske båtgravfeltene vi må vende oss til. Her viser også gravfeltene at krigernes ledere var ryttere. De paraderte sittende i dekorerte sadler på sine hester hvis seletøy var utstyrt med beslag av forgylt bronse med ornamentikk i Stil II. På hodet bar de prakthjelm, og våpenutstyret bestod av sverd, lanse, pil og bue og skjold.

De fire gravfeltene Tuna (i Alsike), Ulltuna, Valsgårde og Vendel var anlagt langs den sjøveien som gikk fra Mälaren inn i Fyrisåen og videre nordvestover på Vendelåen. Havnivået var flere meter høyere enn i dag, og Mälaren var en vik av Østersjøen. Mange elver var viktige trafikkleder for båter i sommerhalvåret og for trafikk med slede og ski i vinterhalvåret. Derfor virker det så selvklart at de hjelmkledte krigerne (og de som ikke hadde hjelm) ble gravlagt i en klinkbygget båt omgitt av sine ridehester. Flere av hestene var dessuten utstyrt med isbrodder for ferd på isbelagte elver og sjøer. Samtlige gravfelt har vært benyttet gjennom mange generasjoner fra eldre jernalder til middelalderen. Gravskikken omfattet både brenning og jordfesting, men krigergravene som dekker perioden fra ca. 550-800 er alle ubrente. Det var 14 graver i Vendel, men det har sikkert vært flere, og de lå tett sammen syd for kirken. Syv graver var båtgraver, og båtene varierte fra syv til ti meter i lengde. Fire av gravene inneholdt en prakthjelm eller rester av en slik. Ettersom både gravfeltene i Ulltuna og Tuna hadde vært utsatt for ødeleggelse var det et hell at gravfeltet i Valsgårde, bare 3 km nord for Gamla Uppsala, var inntakt og kunne totalundersøkes av arkeologer. Som i Vendel hadde gravfeltet vært anvendt gjennom mange hundre år; fire båtgraver dekker omtrent tidsrommet 650-750 og 11 er fra vikingtiden. Ornamentikken på båtgravenes praktgjenstander danner grunnlaget for en oppdeling av Stil II i flere kronologiske grupper fra A til E.

Grav 6 i Valsgårde representerer et slags gjennomsnitt av båtgravene. Den inneholdt en 10 meter lang båt av gran og hadde plass til fire eller fem par roere. Akterut i båten var den døde krigeren blitt lagt på dunfylte puter og madrass. På sin venstre side hadde han to sverd og et huggsverd samt to pokaler av glass fra Rhinområdet, og på sin høyre side nok et huggsverd. Alt var så blitt dekket med flere lag tepper og matter av bjørkenever, muligens et slags telt eller baldakin. To skjold stod støttet mot babord reling og ett på styrbord side. Et stykke fra den dødes føtter lå to hodetøy til hester med beslag og bissel og to bunter med piler, en verktøykiste og diverse tyngre jernredskap. På bunnen av båten mot forstavnen lå hjelmen. I en rekke skrått over båten lå to belter med beslag, en spydspiss, en skål av glass, et spillebrett av tre med spillebrikker, et bandolær. I forstavnen lå diverse kokeutstyr av jern samt proviant i form av skinker etc. Inne i båten lå en hest og tre hunder og utenfor nok en hest og en okse.

Mennene i båtgravene var ikke utstyrt med smykker av edelmetaller eller granater i cloisonné, og alle de dekorerte beslagene er av forgylt bronse. To av hjelmene og to av sverdene har riktignok innlegg av granater, men arm- eller halsringer av gull forekommer ikke. Hjelmene er de mest iøynefallende av våpenutstyret. De er såkalte nordiske kamhjelmer laget av jernbånd og jernplater. De har en karakteristisk kam over issen enten i form av et ornert bånd med dyreornamentikk eller som en høy kam som ender i et dyrehode foran og bak. Hjelmene er prydet med bilder i pressblikk med en rekke motiver der krigere i prosesjon, rytterkrigere i kamp, våpendansere og dyretemmere er de vanligste motivene. Ørnen og villsvinet finnes på hjelmenes kam og signalerer krigerens kampvilje og mot samtidig som disse dyrene er knyttet til Odin og Frøy. Den mest forseggjorte av de nordiske hjelmene ble funnet i den angliske kongen Raedwalds grav i Sutton Hoo i England fra tidlig 7. årh., og den viser med all tydelighet at hjelmen helst har vært et rang- og verdighetstegn. De frankiske kongenes hirdledere fikk sine hjelmer av kongen som tegn på sin rang, og hjelmene bar kristne symboler. Kanskje kan derfor billedprogrammene på de nordiske kamhjelmene med sitt hedenske innhold tolkes som en reaksjon på det kristne budskapet. Hjelmene ble holdt høyt i ære, og de fleste må etter slitasjen å dømme ha vært ganske gamle da de kom i graven, dvs at de gikk i arv sammen med rangen som leder av kongens hird. Hjelmene ble derfor ikke plassert nær den døde, men foran ham i bunnen av båten.

De svenske båtgravene representerer en periode da kongeslekten med basis i Gamla Uppsala var sterkt innfluert av frankerne. Sveakongene selv ble kremert og begravet i enorme gravhauger, men hirden ble etter frankisk skikk gravlagt ubrent med sitt parade- og kamputstyr på egne gravplasser. Hirdlederne, som selv har vært av høy rang, har svoret troskapsed til kongen og har som pant på dette forhold fått en prestisjefylt gave, gjerne et ringsverd. Krigerne i hirden hadde krig som sitt métier. De hadde en bestemt livsstil og trenet seg i kamp fra de som ganske unge gutter ble opptatt i fellesskapet; deres ritualer var i første rekke knyttet til Odin, den store krigsguden. Det gammelengelske heltediktet om Beowulf handler nettopp om livet i kongens store hall, om store farer som den gode helten overvinner og om hans død og begravelse. Beowulf betyr bie-ulv, med andre ord: bjørn. Bjørnen var kanskje heltens følgedyr, og hans bjørne-jeg var så sterk og uredd at han kunne drepe udyret Grendel og hans farlige mor.

Dronningen i hallen

Noen vil kanskje tenke at disse krigerne må ha hatt mødre, søstre, koner og friller og undre seg over om de finnes med i det arkeologiske materialet fra helt- og krigertiden. Husfruene med sine nøkler og seende evner fantes nok fortsatt, men deres rolle hadde muligens endret seg. På den annen side var branngravskikken som appellerer svakere til forskerne, fremherskende. I Beowulf-diktet finnes det en kvinne, danenes dronning Wealtheow, som gir et bilde av den mektigste husfruens rolle når krigerne sitter benket i kong Hrodgars hall Heorot:

”So the laughter started, the din got louder, and the crowd was happy. Wealtheow came in, Hrothgar’s queen, observing the courtesies.

Adorned in her gold, she graciously saluted the men in the hall, then handed the cup first to Hrothgar, their homelands guardian, urging him to drink deep and enjoy it, because he was dear to them. And he drank it down like the warlord he was, with festive cheers ” (Oversettelse Seamus Heaney).

Inne i hallen ved de rituelle gjestebudene der bloting til gudene fant sted, spilte husfruen rollen som seremonileder. I eposet gir hun kongen først å drikke, fremhever ham som god og gavmild og rekker deretter hver og en av gjestene og sist Beowulf pokalen med mjød. Hennes rolle var naturligvis også å styre husholdet, se til at det fantes nok av mat og drikke til gjestebudene og ta hånd om det gjestene hadde med seg som gaver. Men hun ga også kongen råd om gaver til gjester såvel som til krigere og om rangordningen av krigerne på langbenkene når det var gjestebud. Den som hadde lavest status satt nede ved døren der det trakk verst.

Mye av det arkeologiske materialet fra denne tiden er nettopp kvinnesmykker. Dyrespenner i form av en hest er uvanlig, men ormer kveilet i 8-tall og S-formete ormer med et hode i hver ende har vært vanlige. De små gotlandske ryggknappspennene har alltid kraftige rovfuglhoder nederst på foten. Den ørn som finnes som prydbeslag på skjoldbrettene i Valsgårde grav 7 og i kongegraven fra Sutton Hoo finnes som draktspenner for kvinner særlig i Mälarområdet. Derved knyttes hirdens symboler også til kvinnene idet ørnen er et symbol for Odin. Det finnes en beltespenne av bronse funnet på Sjælland der et mannshode en face flankeres på hver side av tre profilsette hoder,- ørn, villsvin og ulv og det samme motivet finnes på et skjoldhåndtak i Valsgårde grav 7. Dette tre-dyrs-tegnet er sjeldent i Norden, men vanlig på kontinentet. Det kan symbolisere Odin og hans sjamanistiske hjelpeånder, men det kan også være skapt under innflytelse av kristendommens treenighet eller tidlig kristne fremstillinger av Kristus omgitt av dyresymbolene for tre av evangelistene Johannes, Markus og Lukas: ørnen, løven og oksen.

Stil Ils dyrefigurer kan ha hatt en apotropeisk dvs ondtavergende virkning når de finnes på kvinnesmykker men har samtidig vist hvilket samfunnssjikt kvinnene tilhørte. De har også gitt andre signaler til omgivelsene som er beslektet med folkevandringstidens relieffspenner. De elegant svungne dyrefigurene i jevn rytme gir inntrykk av en annen og mer kontrollert estetikk enn tidligere. Men hva slags dyr som inngår i motivene er nesten umulig å avsløre. Det synes som om ulveliknende dyr og ørner med kraftige, krumme nebb etterhvert viker plassen for mer hesteliknende dyr. Hestens rolle både som sakralt dyr og som en viktig faktor i strid og som fremkomstmiddel for samfunnets elitesjikt øker markant mellom 6. og 8. årh.

Storgods og protobyer

De samfunnsmessige endringene i 6.-7. årh. fremgår også av de arkeologiske strukturene i landskapet,- landsbyer og storgårder. Gudme-området på Øst-Fyn med sin handels-og håndverksplass Lundeborg hadde sin storhetstid mellom 4. og 6. årh., men det fortsatte som storgods frem til middelalderen. Sorte-Muld-området på Bornholm, derimot, hadde sin storhetstid mellom 6. og 8. årh. Uppåkra nær Lund i Skåne mellom 5-10 årh., mens Helgö i Mälaren synes å ha vært Nordens største metallhåndverksområde mellom 4. og 6. årh. Dets sakrale betydning, derimot, avtok ikke før i vikingtiden. Denne typen boplasser kan man kanskje kalle storgodser med kultiske sentrumsfunksjoner. Slike gods har neppe hatt inntekter fra egen gårdsdrift, men fra andre gårder som hadde et avhengighetsforhold til godseieren/småkongen og hans familie, og fra innsamling av tributt i form av diverse jordbruks-eller jaktprodukter, håndverksprodukter og prestisjevarer men også av gaver. Flere slike gods etableres etter folkevandringstiden som f.eks. Tissø med et rikt arkeologisk materiale fra 7.-10. årh. og Lejre med materiale som dekker det samme tidsrommet, begge på Sjælland. I løpet av 8.-9. årh. synes det å inntre en endring fra et system basert på tributt til et godssystem basert på egen gårdsdrift i Syd-Skandinavia sannsynligvis i forbindelse med samtidige endringer i politiske maktrelasjoner. Storgodsene, som ikke har vært mange, har hatt store hallbygninger og en krets av mindre gårder knyttet til hovedgården. I slike enorme hallbygninger har fyrsten samlet sine allierte, frender, venner og krigere til storstilte kultiske gjestebud. Der fikk gudene sine offer og fyrsten hyllning av skalden mens den søte mjøden og det dampende hestekjøttet fikk krigerne til å love mangt et fremtidig storverk. Storgods viser at det allerede i 8. årh. i Norden finnes et jordeiende aristokrati som øker sin makt fordi kongens makt ikke er sterk nok. En rekke mindre handels-eller markedsplasser anlegges i denne tiden antakelig av storgodseierne. Først i allianse med kirken og dens nedarvete strukturer kunne kongemakten styrkes og legge grunnlag for rikskongedømmene.

I 8. årh. anlegges de første byene, eller kanskje helst protobyene, i Skandinavia, nemlig Ribe i Vest-Jylland, Hedeby i Schleswig, Åhus i Skåne, Birka på Björkö i Mälaren og Skiringsal i Vestfold. De anlegges trolig på kongelig mark og karakteriseres av en felles plan med smale markteiger som ligger parallelt opp fra stranden. På hver teig ble det satt opp en bod eller oppført et hus for en håndverker,- en perlemaker, en bronsestøper, en kammaker, en veverske. Det er uklart om bebyggelsen var helårlig i den første tiden eller om den var basert på virksomhet bare i sommerhalvåret.

På kontinentet ble den siste av de langhårete merovingerne i 751 etterfulgt av Pepin den lille som ble kronet til konge over frankerne med pavens velsignelse, den første av det arnulfiske eller karolingiske dynasti. Hans sønner Karl og Karloman samregjerte i tre år, men fra 771-814 regjerte Karl den store, Carolus Magnus alene. Han allierte seg med romerkirken, og ble med pavens velsignelse kronet til keiser i Peterskirken i Roma første juledag år 800. Under det karolingiske rikets største utbredelse og blomstringstid var innflytelsen på de skandinaviske områdene ulike sterk. Fra bispesetet i Hamburg sendtes det ut misjonærer, først til Friesland og senere til Norden for å omvende menneskene til den rette tro. Det var kongene og aristokratiet som først måtte vinnes for kristendommen, deretter ville resten av folket følge etter. Om kristningsforsøkene i Hedeby og Birka finnes det en skriftlige samtidig kilde, biskop Rimberts biografi over sin forgjenger og læremester Ansgar, som gir glimt av de frankiske misjonærenes liv blant ”de ville” skandinaverne.

Skipet

Nordens befolkning i jernalderen bodde langs kysten, ved seilbare elver og større innsjøer, og båtbygging må tidlig ha blitt en profesjon der det fantes godt med skog. Merkelig nok ser det ut til at man i Norden har hatt en felles båtbyggingstradisjon med klinkbygde skrog. Regionale forskjeller har sikkert eksistert, men de er vanskelige å skille ut i det sparsomme, arkeologiske materialet. Frem til vikingtiden ble skipene rodd.

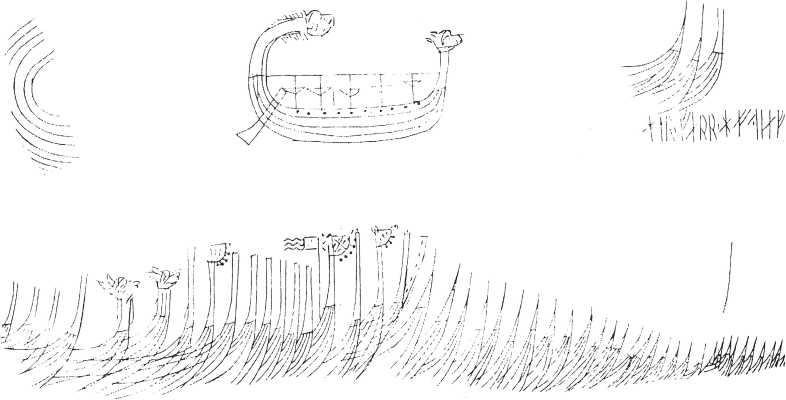

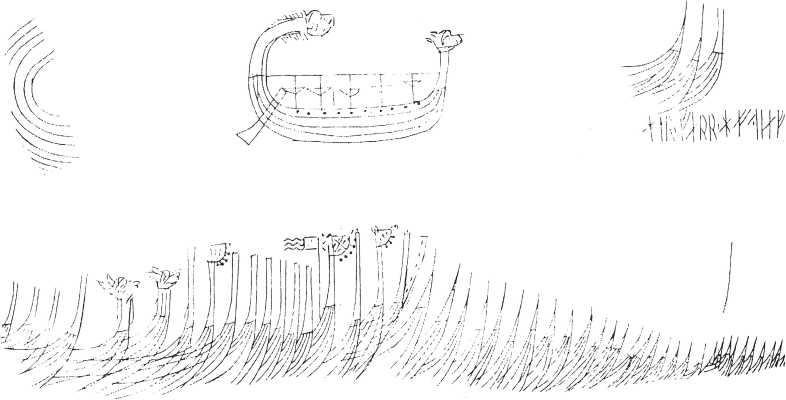

Det 23 m lange roskipet fra Nydam mose fra 5. årh. er et godt eksempel. Først omkring 800 e.Kr. har vi et håndfast bevis for at det ble det bygget skip med en ordentlig kjøl som er forutsetningen for at fartøyet skal kunne bære en mast med seil, nemlig Osebergskipet. Men på gotlandske billedsteiner fra 6. og 7. årh. finnes det seilførende skip, og på billedsteiner fra 8. årh. ses skip med mast og seil og komplisert takellasje. Dessuten finnes det en lang runeinnskrift fra tidlig 7. årh. fra Eggja i Sogn som omtaler både keiper (åretoller) og mast. Her foreligger altså en motsetning mellom det arkeologiske materialet og dokumenter i bilder og skrift.

En unik, liten draktspenne fra Lillevang på Bornholm viser et vikingskip med skjold festet ved relingen og med mast. Øverst i masten finnes en dyremaske en face,- et lite bamseliknende fjes. Skipets forstevn avsluttes med et rovfuglhode med krum hals. Akterstevnen avsluttes på samme måte med et profilsett dyrehode.

Dyrehodene i skipets stevner skulle forsterke inntrykket av det dyre- eller fuglelike ved skipet. Kong Olav Tryggvasons skip het f.eks. Ormen Lange, og vi må tenke oss at forstevnen var prydet med et ormhode og akterstevnen med en opprullet ormekropp. Osebergdronningens skip var bygget omkring år 800, og skipets forstavn har et grinende hode som kanskje skulle skremme landvettene, åndene som beskyttet et landområde. I den islandske Landnámabok står det at, den islandske loven fra før landet ble kristent i 999 hadde en bestemmelse om at man ikke måtte seile mot land med gapende hoder og oppsperrete kjefter slik at landvettene ble skremt. Vikingskipene hadde malte detaljer, og skjoldene langs relingen kunne være en broket samling eller ha samme farge og dekor. På de gotlandske billedstenene er vikingskipenes seil stripete eller rutete, noe som muligens ikke har rot i virkeligheten. Men i mastetoppen eller forut har i alle fall de sene vikingskipene hatt blanke fløyer av bronse med rasleblikk eller fargerike bånd festet i små huller langs fløyens ytterkant. Det finnes en meget berømt illustrasjon gjort med kniv på en knortekjepp fra Bryggen i Bergen av en vikingskipsflåte med dyrehoder eller fløyer i forstevnen (jfr. tegning s. 38).

Slike fløyer må ha vært ganske vanlige i vikingtiden ettersom de også ble støpt i miniatyrutgaver i bronse. Vender man på 112 bildet av minityrfløyen fra Rangsby i Saltvik sn. på Åland blir fløyformen tydelig, og det lille bamseaktige fjeset viser klart slektskap med Lillevangspennens mastehode. De hører til et gripedyr i såkalt Borrestil, oppkalt etter noen forgylte bronsebeslag fra den store skipsgraven på Borre i Vestfold fra ca. 900. Miniatyrfløyer av denne typen er kjent fra tre funnsteder, Åland, Birka i Mälaren og Menzlin i Ostvorpommern, mens en yngre type med et dyrehode ytterst foreligger fra så vidt forskjellige lokaliteter som Novosjolkt nær Smolensk i Russland, Bandlunde på Gotland og Lovö i Mälaren. To forvitrete miniatyrfløyer fra en skadet branngrav i Dalarna i Sverige bringer antallet opp i åtte, noe som tyder på at det er en sjelden, liten gjenstand. Hvordan den har vært anvendt er usikkert. Jan Peder Lamm har foreslått at de har stått på små skipsmodeller som prominente mennesker i vikingtiden hadde i sine haller! De store skipsfløyene fra sen vikingtid, som ble kalt veðrviti, finnes det faktisk tre velbevarte eksemplarer av fordi de endte sine dager som vindfløy på kirker. Det er Soderala kirke i Hålsingland, Heggen kirke i Buskerud og Kållunge kirke på 180-182, 193 Gotland, der fløyen satt på kirkespiret helt til 1930. En eldre tegning viser at fløyene opprinnelig ikke var plassert på kirkespiret som værhaner men at de stod skrått på selve kirkemønet som på langskipene. Forbindelsen mellom skip og kirke i middelalderen er at leidangskipenes seil og utstyr ble oppbevart på kirkeloftene, og det er vel helst de store leidangskipene med sine fløyer som er ”avbildet” på knortekjeppen fra Bryggen i Bergen.

Gripedyret

Vikingtidens kunst er variert og på mange måter annerledes enn i de foregående hundreårene bortsett fra at dyremotivet står sterkt. Flere kunststiler opptrer samtidig, og det er tydelig at den andre halvdelen av 700-tallet representerer en fornyelsesperiode med eksperimentering med nye former og fremstillinger. De smale, båndformete dyrefigurene i symmetrisk oppbyggete, kontrollerte billedstrukturer som karakteriserer den siste av Vendelstilene, Stil D, brytes i Vest- og Sydvest- Skandinavia av en slags blandingsstil (Stil F). Noen har kalt den ”misjonsstil” fordi den er preget av kontinentale kunsttradisjoner tilknyttet anglo-kontinental stil og henger sammen med den sterke misjonsvirksomheten som fant sted fra annen halvdel av 700-tallet til første halvdel av 800-tallet. I 826 kom f. eks. den første misjonæren, benediktinermunken Ansgar til Hedeby, og tre år senere tar han seg med stor møye og stort besvær til Birka i Mälaren. Det finnes også en Stil III/E som særlig forekommer på Gotland i slutten av vendeltid og fortsetter å utføres i tidlig vikingtid på store, barokke ryggknappspenner der hver del er støpt som en hul eske. Eskenes overside er prydet med innfattete granater, gullblikk og høye knopper. Mange av ryggknappspennene er mesterverk prydet med dyreornamentikk og forgylling på alle flater.

Et nytt motiv av en helt annen karakter kommer til - det livlige gripedyret. Det har fått sitt navn fordi dets fire føtter griper tak i omgivelsene enten de består av en ramme, et annet dyr eller sine egne lemmer. Dets hode er fremstilt en face med store, stirrende øyne og ofte med hårtofs. Det hender at det griper tak i sine egne munnviker så tennene blottes. Gripedyret innleder vikingtiden der kunsten endrer karakter under innflytelse av kristne, orientalske og irske motiver i metallkunst og bokmaleri. Plantemotiver som akanthus og vinranker med fugler og dyr formidles til nordiske metallhåndverkere via vikingenes herjinger i kirker og klostre der store kunstskatter ble røvet, men også via frankiske og angelsaksiske misjonærer som brakte med seg sine liturgiske bøker og gjenstander. Gaveutveksling mellom nordiske konger og høvdinger i politisk hensikt førte også til at nye og egenartete kunstgjenstander kom inn i miljøer der de ble kopiert og gitt en annen funksjon. Et av de klassiske eksemplene er den treflikete spennen, et kvinnesmykke til å holde sammen en kappe eller kåpe på brystet. Opprinnelig var den treflikete spennen en remfordeler til et frankisk sverdoppheng og var dekorert med planteornamentikk. Men vikingtidens våpenføre menn bar sverdet i beltet uten bandolær og forærte sine kvinner den frankiske remfordeleren omgjort til hengesmykke eller spenne. Raskt ble formen opptatt av smykkesmedene og utstyrt med nordisk ornamentikk, noe den egnet seg vel til.

De tre tidligste stilgrupper i vikingtiden kalles Broa, Berdal og Borre etter funnsteder for viktige funn, og gruppene er utskilt på grunnlag av dyremotivenes formmessige forandringer. Men på en og samme gjenstand kan flere stiler være representert, noe som viser at de overlapper hverandre i tid. Gripedyret utviklet seg etterhvert til en liten bamseliknende skapelse, ”Borredyret”, og tre slike gripedyr er et vanlig motiv på de treflikete spennene. Gripedyrmotivet ble veldig populært, og nordboerne tok det med seg til de Britiske øyer, der det i de senere år er kommet mange gode eksempler takket være metalldetektorene. To norske funn viser at gripedyrmotivet også kunne friste den hendige til rundskulptur. Figurene, to bjørner (?) som holder i hverandre og et fantasidyr med blottete tenner er laget av jet, et amorft stenkull som bare finnes i England og som var populært til smykker, særlig armringer. Hvor gripedyret ble til og hva som var inspirasjonen til et så awikende dyremotiv, er ikke klarlagt. Men at det er et fremmedelement i nordisk kunst er alle enige om, og muligens kommer inspirasjonen fra England eller fra såkalt anglo-kontinental stil - misjonærstilen. I sin tidlige form er gripedyret sterkt asymmetrisk og ses ofte på nøkler, der det synes å turne inne i nøkkelhodet, men også på ovale draktspenner. I den senere Borrestilen blir gripedyret temmet. Det får bamseliknende hode med ører og en kropp som er ordnet symmetrisk om en ryggrad/midtakse. Men hva symboliserer gripedyret? Ingen vet, men dets apotropeiske betydning burde være sikker.

Kvinner skaper klær, menn støper smykker

Kvinnedrakten i vikingtiden var ganske stereotyp, men dens faste smykkeinventar ga gullsmedene muligheter for å briljere i de skiftende ornamentstilene. Innerst bar kvinnen en lang serk av lin som kunne være plissert og ble lukket i halsen med en liten, rund spenne. Derover bar hun en selekjole og ytterst en kappe eller kåpe. Til festdrakten, som hun var ikledt for sin siste reise, hørte det ikke belte. Men til hverdags kan hun ha hatt et tekstilt belte til kniv og nøkler slik som folkevandringstidens husfruer. Selekjolens seler bestod av to løkker av stoff, to lange som gikk fra ryggen over skuldrene og to korte på forsiden. Løkkene ble festet sammen ved hjelp av en oval, skålformet spenne av bronse på hver side av brystet, og det er særlig disse spennene som ble utstyrt med rik ornamentikk. Den ovale spennen skapes allerede i 8. årh. og minner om et sammenkrøpet urtidsdyr, en slags trilobitt, sett ovenfra. Men den typiske ovale draktspennen ble tydeligvis skapt av en kunsthåndverker i Ribe i slutten av 8. årh. og kalles Berdalspenne etter et funnsted i Vest-Norge. Derfor ble den tidlige vikingtidens dyrestil med gripedyr tidligere kalt Berdalstil. Utover i vikingtiden ble de ovale spennene serieprodusert i stadig større og bredere utgaver og dessuten utstyrt med en brem nederst. Nihundreårenes serier av ovale spenner har dobbelt skall,- et glatt, forgylt underskall og et overskall i gjennombrutt mønster inndelt i felter ved hjelp av listverk. Listene ble dekorert enten med hvitmetall og niello eller med pålagte, flettete sølvsnorer. Der listene krysser hverandre, satte gullsmedene gjennombrutte knapper av forgylt sølv eller bronse så hele overflaten ga et levende, plastisk inntrykk. Den samme plastisiteten preger også de gotlandske dåseformete spennene og enkelte likearmete spenner. Mellom de ovale spennene hang kvinnene rader av fargerike perler av glass, rav, karneol og små amuletter av sølv. I yngre vikingtid var det vanlig med en ring festet til bremmen der en kniv, en nøkkel eller annet kunne festes. Da vikingtidens kvinnedrakt gikk av mote i 10.-11. årh. i Skandinavia, skapte de finske og baltiske smykkesmedene en smalere, spissoval variant med egen ornamentikk.

De gotlandske kvinnene bar en liknende drakt med selekjole men uten ovale spenner. Her var de erstattet med relativt små, dyrehodeformete spenner av bronse. Hodene ser ut som en blanding av bjørn og svin med tydelig tryne og små, runde ører. Det er ikke antydning til øyne. På baksiden finnes en bunnplate til feste for nål og nåleskjede. Forsiden av spennene er delt inn i felter ved hjelp av listverk og dekket av dyreornamentikk eller bare prikker. Mellom dyrehodespennene hengte kvinnene flere kjeder av bronseringer festet til kjedeplater formet som masker. Slike gikk av moten i yngre vikingtid, men bronsekjeder festet til runde eller spissovale draktspenner levde videre som en viktig del av den finske kvinnedrakten i sen vikingtid og tidlig middelalder. Typisk for Gotland er hengesmykker i form av fiskehoder i bronse som ble tredd ved siden av hverandre i lange kjeder og festet til de dyrehodeformete spennene. Ved vikingtidens slutt hendte det at man festet sammen to og to fiskehoder ved hjelp av nitter og gjorde dem om til en draktspenne med nål på baksiden. De runde, dåseformete spennene som holdt sammen ytterplagget foran var også noe helt eget for Gotland. I resten av Norden brukte kvinnene i tidlig vikingtid en likearmet spenne eller en trefliket spenne og senere runde, gjennombrutte spenner med fremstilling av en profilsett rovfugl eller formet som en dyrefigur sett ovenfra. Kvinnedrakten med parspenner synes å ha vært forbundet med en kvinnerolle som ikke var mulig etter at kristendommen fikk fotfeste i Skandinavia. Dyreornamentikken på draktens ovale og andre spenner hang trolig sammen med de ritualer som kvinnene stod for og som hørte til de nedarvete trosforestillingene der seid var en viktig del.

Vikingtidens våpenføre mann bar få smykker. En ringspenne eller en ringnål av sølv eller bronse til å feste kappen over skulderen var det viktigste. En liten spenne lukket tunikaen i halsen, og livremmen kunne være utstyrt med remspenne og beslag av bronse. Sverdet i sin dekorerte sverdskjede var mannens fremste statusobjekt. Var klingen mønstersmidd og knapp og hjalter prydet med ornamentikk i edelmetaller eller kobber, ga det et tydeligere budskap om mannens status enn noe smykke. De store ringnålene av sølv er meget sjeldne i gravfunn, men dessto vanligere i sølvdepotetene fra vikingtiden både i Norden og på De britiske øyer. Der bar menn ringspennen med nålen opp, og den antok etterhvert en slik lengde at den ble farlig for omgivelsene.

Jellingestenen

De sene kunststilene i vikingtiden er knyttet til typiske aristokratiske miljøer og har navn etter funnstedet for de mest karakteristiske objektene, Jelling, Mammen, Ringerike og Urnes. I de tre sistnevnte er motivene hovedsakelig store, klart tegnete firbente dyr og store fugler. Jellingestenens store, løveliknende dyr i kamp med slangen er ikke tegnet i Jellingestil men i Mammenstil. Opprinnelsen til motivet det store dyret har man søkt i kontinental og angelsaksisk kunst, men uten å løse problemet. Både fornnordiske og kristne myter kan ligge til grunn for fremstillingen og avspeiler den overgangstiden kunststilene er blitt til i.

”Kong Harald bød gjøre denne kuml etter Gorm sin far og etter Thyra sin mor. Den Harald som for seg vant hele Danmark og Norge og gjorde danene kristne.” Dette er den 2,4 m høye Jellingestenens korte og pregnante budskap i runer. Dertil kommer fremstillingen av Kristus som den seirende herskeren bundet av ormliknende båndslyng på den ene av stenens billedsider med teksten ”og gjorde danene kristne” under. Det store firbente dyret med ormen finnes på den andre billedsiden. Kong Harald Blåtann stod med ett ben i den gamle verden med sine trosforestillinger og med et i den nye verden med kristendommen. Det avspeiles i hele komposisjonen av dette dynastiske anlegget med de to kjempemessige haugene, med kong Gorms minnesten over sin hustru Thyra, Harald Blåtanns monument og kirken. Haugene ble undersøkt i 1820 og 1941. Den nordre inneholdt en plyndret kammergrav og den andre viste seg ikke å være noen gravhaug. Begge er bygget over en 170m lang skipssetning. Under 1100-tallskirken, som ligger mellom haugene fant man i slutten av 1970-årene sporene etter tre eldre kirker, hvorav den eldste antagelig er den som kongen lot bygge da han ca. 960 gikk over til kristendommen. I kirken fant man en kammergrav med restene etter to personer som vel er Thyra og Gorms jordiske rester og som sønnen Harald flyttet til en kristen grav etter sin egen omvendelse. I Nordhøjen ble det bl.a. funnet et stort vokslys og et ørlite sølvbeger på fot, delvis forgylt og med en dekor som har gitt navn til tidens kunststil, Jellingestilen. På 186 Jellingebegeret, som antakelig er en kristen reisekalk, ses to båndformete dyrefigurer med løftet forben på hver side av en kurvliknende figur med to vifteformete akanthusblader.

Jellingestilen, som i sin tidlige fase er todimensjonell og flatedekkende, har som hovedmotiv et båndformet, profilsett dyr i S-form med hale. Det har hode med stort øye, åpen munn med lang tunge og av og til en huggtann. Fra hodet går det ofte ut en nakketofs, og kroppen er tverrstripet eller/og perlet. Slektskapet med Stil III er tydelig, og det er mulig at stilen er oppstått i det skandinaviske miljø i York. Ettersom denne dyrestilen også er belagt i skipsgraven fra Gokstad i Vestfold, har man ved hjelp av dendrokronologi kunnet datere Jellingestilens tid mellom slutten av 9. årh. og midten av 10 årh. Den har tydeligvis hatt en tilknytning til kongelige kretser og til aristokratiet.

Mammen

Bjerringhøj, en relativt liten gravhaug i Mammen sør for Viborg ble plyndret i 1868. Den dekket over et kammer 3m x l,9m med vegger av stående, tiløksete eikeplanker og 6 takbærende stolper. I en plankekiste lå en mann og antagelig en kvinne i praktfulle klær med broderier og gullinnvirkete bånd. Gravgodset som gikk an å rekonstruere, bestod av en jernøks helt dekket av ornamentikk innlagt i sølv, minst ti paljetter av gullblikk fastsydd på drakten, tekstilrester samt to armbånd av tekstil. Dessuten fantes pelsrester av murmeldyr, en udekorert jernøks, to trespann, en bronsekjele, spillebrett (?) og et 3,7 kg stort vokslys. Begravelsen har foregått i år 970/971, da Danmark offisielt var kristnet, men bortsett fra vokslyset viser graven ingen spesielt kristne trekk. Den praktfulle øksen har en profilsett fuglefigur på den ene siden av bladet og et stilisert tre på den andre. Treet kan tolkes både som asken Yggdrasil og som det kristne Livets tre, og fuglen som både hanen Gullenkamme som galer for å varsle æsene om at verdens undergang, Ragnarok er nær eller som Fugl Fønix, et kristent symbol for Kristus og oppstandelsen. Det er sannsynlig at paret i Bjerringhøj hørte til Harald Blåtanns krets.

På kjøretøyet skal storfolk kjennes

I et grustak i nærheten av Mammen kirke ble det i 1871 funnet et håndverksdepot inntullet i linstoff. Det inneholdt pressblikk med menneskemasker, en bronsepatrise til et rektangulært beslag, et låsebeslag av bronseblikk, fragmenter av minst to bronsekar samt ornamenterte kant- og endebeslag til to høvrer (mankestoler) av tre. Beslagene er av forgylt bronse og fylt til bristningspunktet av båndformete dyrefigurer, ormer og en liten kvinnefigur med en plante i hånden (Bind 1, 39), alt i Jellingestil med innslag av Mammenstil. Endebeslagene er formet som plastiske dyrehoder med åpen kjeft, omslynget av ormer og med en plastisk dyrefigur i den åpne kjeften.

Prakthøvrer som disse fra Mammen kjennes bare fra Danmark - fra Elstrup på Als, Møllemosegård ved Nybølle på Fyn og de aller fornemste - et par fra en plyndret gravhaug i Søllested på Fyn. De henger sammen med vogner, veier og et samfunnssjikt som stod over vanlig folk og lot seg frakte ved spesielle anledninger. Det finnes firhjulte vogner i Jylland fra førromersk jernalder, bl.a. de elegante vognene fra Dejbjerg præstegårdsmose sørøst for Ringkøbing. Men det er vel usikkert om de ble brukt i verdslig øyemed. Tacitus forteller i sin bok om germanerne fra år 98 e.Kr. om den germanske gudinnen Nerthus hvis bilde om våren ble fraktet rundt i en vogn trukket av kyr. Men for de danske sene vikingtids vognene har hesten vært trekkdyret. Hest og vogn har ikke vært så uvanlig som prakthøvrene antyder, men ellers i Skandinavia har høvrene har vært enklere. De har vært av tre, men øverst har det sittet et ornamentert bronsebeslag med plass til en tømme i hvert sitt hull. I skipsgraven fra Oseberg i Vestfold fantes en vogn med rike utskjæringer. Vognen består av en løs vognkasse på et hjulstell av massive hjul med korte eiker inn mot hjulnavet. Denne vognen kan ikke svinge, men bare rulle rett frem ved hjelp av to trekkdyr og har således neppe vært et vanlig kjøretøy. Til Osebergkvinnens utstyr hører også et langt billedteppe, en revle med fremstillinger av bl.a. kultiske opptog med såvel overdekkete vogner trukket av hester som vogner med passasjerer. Fire dyrehodestolper av tre med rik utsmykning i karveskurd bør trekkes frem i denne sammenhengen. De er både form- og motivmessig beslektet med endebeslagene på de danske prakthøvrene og har som dem sikkert vært knyttet til bestemte ritualer der opptog med vogn inngikk. Vogner trukket av hester er fremstilt på en av de gotlandske gravkistene, slike som bare ble benyttet til kvinner. Såvel gravfunn som litterære henvisninger gir inntrykk av at den fornemme kvinnens fremkomstmiddel i vikingtiden var den hestforspente vognen mens mannen red. Men at hest og vogn ble brukt i helt bestemte sammenhenger gir også Søllestedhøvrene bud om.