Scania's Stone Sculpture During the 12th Century

10000 ÅRS NORDISK FOLKKONST

Det saknas inte större verk och mindre uppsatser rörande den nordiska forntida- och medeltida konsten, men ofta är framställningen av denna bildvärld endast en redogörelse för stilutveckling, sammanhang med samtida europeisk konst, kronologi och teknik. Här vill man gå en annan väg, låta bilderna tala för sig själva, endast åtföljda av en introduktion och av de nödvändiga fakta om de avbildade konstverken.

Denna väg är framkomlig, därför att konstnären och vetenskapsmannen har slagit följe. Således utväljer och sammanställer konstnären bildernas inbördes sammanhang i den grupp, som skall behandlas, samlar ihop dessa bilder till ett fortlöpande collage, så att de kan ses både var för sig och i ett sammanhang, medan vetenskapsmannen tillför dem en nödvändig dokumentation.

En sådan förbindelse har redan skapats för ett kvarts sekel sedan, då en krets av unga konstnärer och vetenskapsmän gav ut tidskriften »Helhesten«, i vilken de sökte visa samspelet mellan bildkonsten och det övriga kulturlivet, bl.a. arkeologi och etnografi.

Ur detta samarbete uppstod — liksom på ett träd — en klyka, vars två grenar var konst och vetenskap, planterade i fruktbar jord och med lövverk från gemensam rot.

För de flesta av »Helhästarna« fick detta stor betydelse, och detta fortsattes genom personliga kontakter till idag, långt utöver tidskriftens två framgångsrika årgångar, vilka nu hör till konsthistoriens största sällsyntheter.

Det är egendomligt att tänka sig, att den mest särpräglade nordiska konsten inte finns på konstmuseerna, utan på kulturhistoriska museer och ute i landskapen som monument.

Det är kanske därför den hitintills inte varit tillräckligt erkänd och värderad.

Men det är denna konst, som detta verks många band skall bringa till allmän kännedom, och inte endast till de nordiska folken, utan till hela världen, därför att denna konsts universella betydelse är självklar.

P.V. GLOB

NORDISK MEDELTID

BAND I

Skånes stenskulptur under 1100-talet

TEXT: ERIK CINTHIO

FOTO: GERARD FRANCESCHI

KOMPOSITION: ASGER JORN

10000 ÅRS NORDISK FOLKKONST

PRIVATUPPLAGA

© ASGER JORN 1965

DE FOTOGRAFISKA REPRODUKTIONSRÄTTIGHETERNA

TILLHÖR SKANDINAVISK INSTITUT FOR

SAMMENLIGNENDE VANDALISME, SILKEBORG

PRIVATUPPLAGA

KAN INTE FÖRSÄLJAS, RECENSERAS ELLER

INGA I OFFENTLIGA BIBLIOTEK

DENNA BOK

ÄR ÖVERLÄMNAD TILL

Universitets biblioteket København fra Asger Jorn. 2-7-65

JENS AUGUST SCHADE

Ih, hvor er det stærkt,

hvor er det overvældende stærkt

at se varm og jordisk kærlighed

hugget ud i sten, saa luften

udenom kunne trænge sig ind

hvor der før kun var stolte stenmasser.

»Kys mig« siger den ene sten nu til den anden »og gør mig skør.«

»Jeg har i tusinde år kun ventet

på at Du sagde det, før jeg dør.

Den der har skabt os i dette digt

har nu fortalt, vi har levet før.«

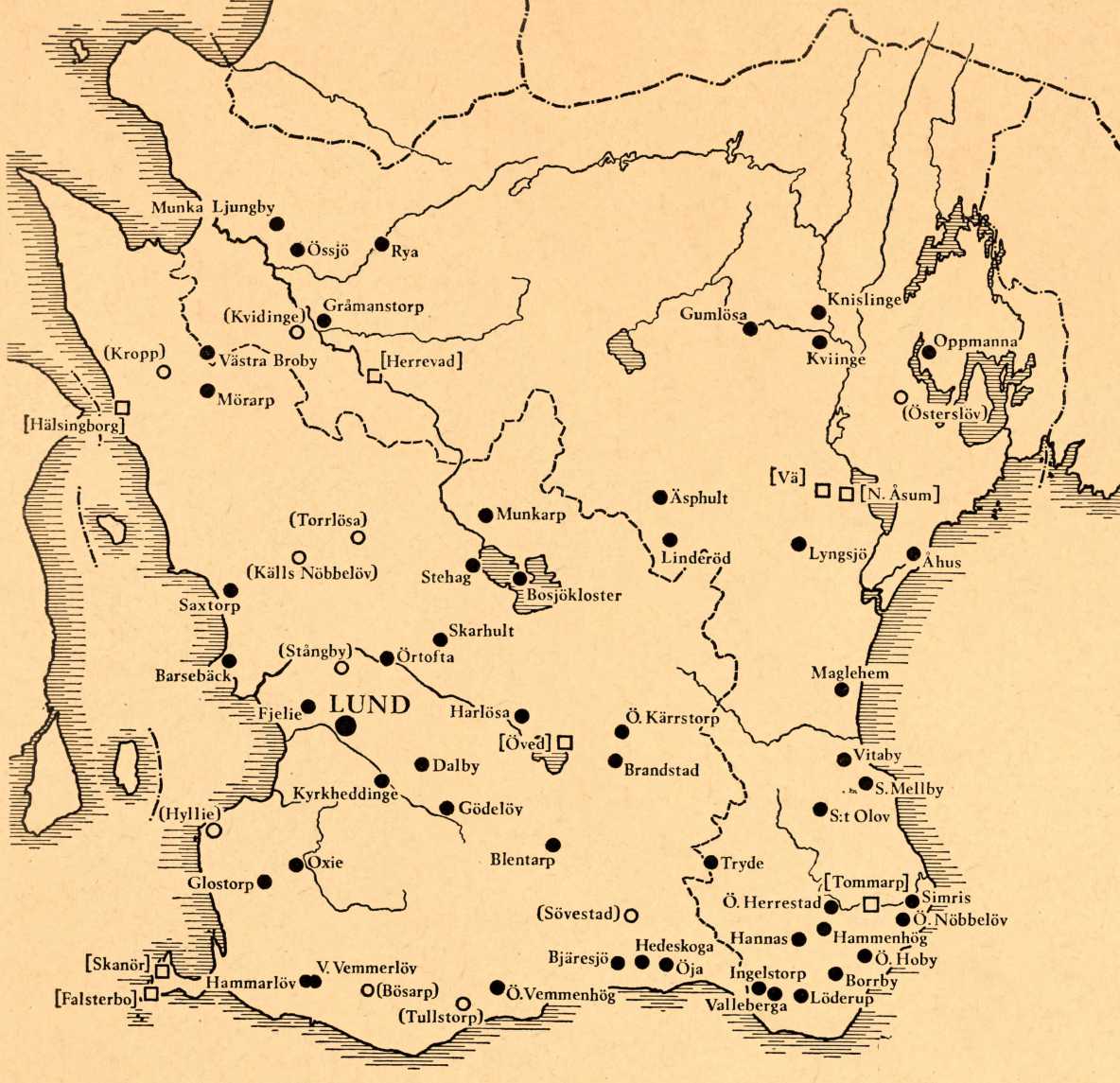

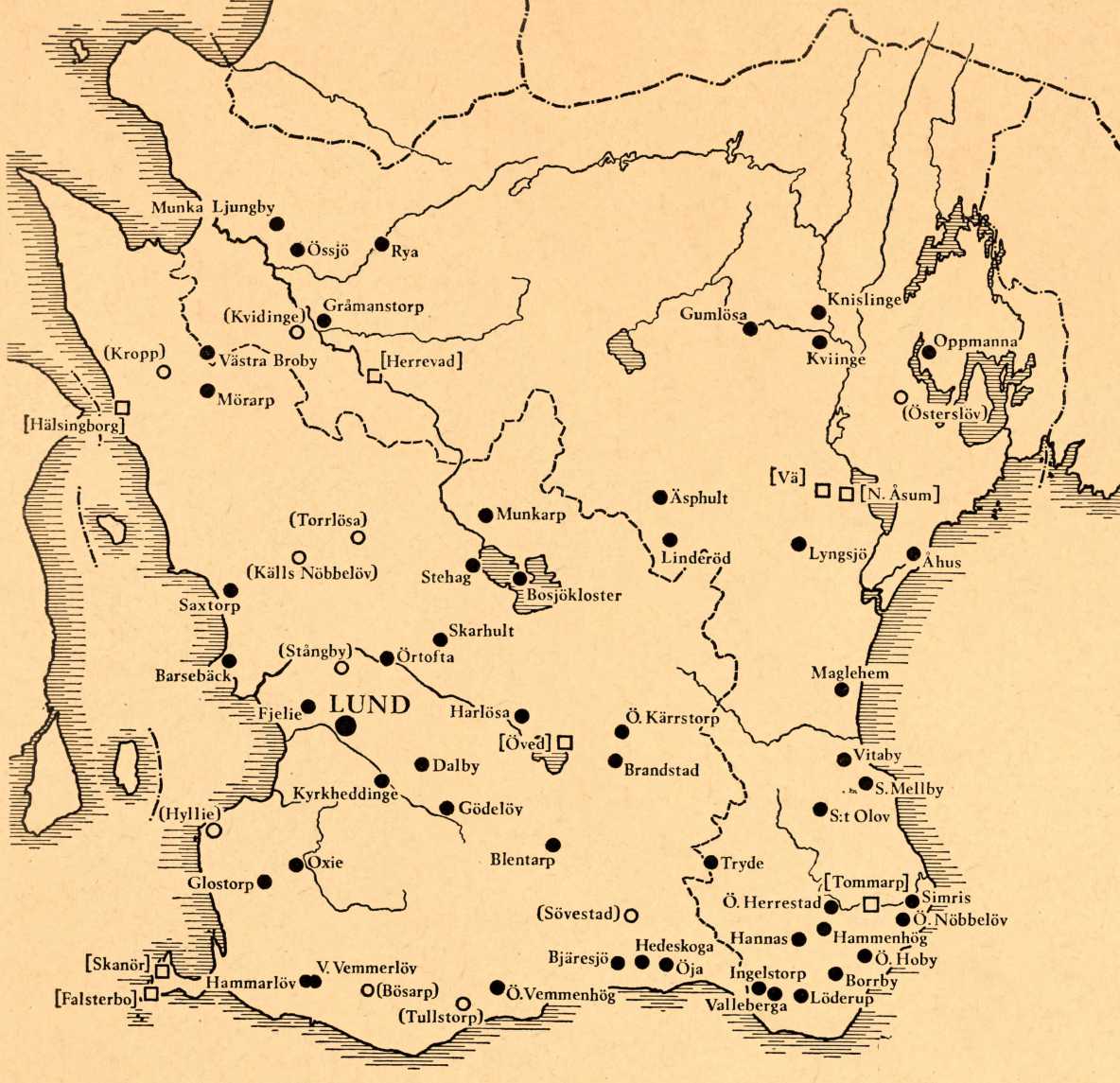

● Kyrkor från vilka skulpturer finns avbildade i denna bok.

○ Kyrkor i vilka avbildade skulpturer befunnit sig men nu förvaras i Lunds universitets historiska museum (LUHM).

□ Orter endast nämnda i texten.

SKÅNE

Under århundradena närmast efter Kristi födelse började romarna så smått lära känna de äventyrliga länderna vid oceanens norra rand. Bland de stora öar man här fick kontakt med har särskilt en med namnet Scandia, på grund av sin bördighet och hemvist för betydande folkstammar, gjort ett starkt intryck på resenärerna, geografernas och historieskrivarnas sagesmän. Att Scandia i verkligheten ej var en ö utan en halvö hade man ännu inte klart för sig. Det råder numera inget tvivel om, att det Scandia man i första hand mötte var det nuvarande Skåne. Men namnet Scandia eller Scandinavia, som det ibland skrevs, blev för romarna efterhand en beteckning på hela den skandinaviska halvön, en beteckning som sedan föll i glömska men återupptogs i ny tid och kom att omfatta även Danmark. Redan tusen år före vår historiska tid kom alltså den dåtida kulturvärldens uppfattning om Skåne att förläna landskapet en sådan ställning att det fick ge sitt namn åt hela den skandinaviska Norden.

Landskapet och den historiska miljön

Än i dag intager Skåne i flera avseenden en särställning bland övriga skandinaviska landsdelar. Som den sydligaste utlöparen av den skandinaviska halvön och en gammal dansk landsdel utgör det ett viktigt förbindelseled mellan kontinenten och den höga Norden. Landskapet äger den bördiga jorden, de stora skogarna, de böljande slätterna och de markanta klippiga bergåsarna. Men Skåne äger framför allt havet. På tre sidor är det omflutet av vatten, och det största avståndet från den ena kusten till den andra uppgår ej till mer än 100 km. Det omgivande havet är ej brett och har alltid varit far bart. Det har ej varit en skiljelinje utan en förbindelseled öppen åt öster, väster och söder. Den verkliga gränsen går mot norr i de stora och i gammal tid svårforcerade skogarna mot Småland och Sverige.

Skånes naturliga rikedom som alltid varit en källa till landskapets välstånd, har gjort det eftertraktat för angränsande riken. Det milda klimatet och den goda jorden har gynnat ett jordbruk, vars företrädare från stenåldern och fram till vår tid varit bärare av den skånska kulturen. Havet har givit rikligt med fisk, som i synnerhet under medeltiden med det stora sillfisket blev en betydande europeisk handelsvara.

Från gammal tid äger skåningen en viss särprägel, som hänger samman med landskapets natur och allmänna förutsättningar. Det är än i dag något paradoxalt i det skånska kynnet en påtaglig öppenhet för omvärlden parad med eftertänksamhet ibland misstänksamhet mot det främmande. Skåningen är villig att i största möjliga mån tillgodogöra sig utifrån kommande impulser, men på ett sådant sätt att den egna traditionen ej går förlorad. Helt i överensstämmelse härmed följer, att hans tal ofta är mångtydigt och kan än i dag förbrylla uppsvensken.

Genom dessa märkliga förutsättningar hos en landsdel, som skämtsamt kallas för ett eget rike, har traditionsyttringarna aldrig varit stöpta i en form. Det varierande landskapet med sina skilda livsformer gör att Skåne ej kan fattas eller beskrivas på ett entydigt sätt. Landskapets egenhet ligger just i paradoxerna, vartill kommer en viss form av ambivalens hos skåningen. Han kan när han vill, men han kan också låta saker bero, när ej livet hotas, en pardoxal förening av energi och lättja. Andligen utgör denna grundinställning en förutsättning för ett aktivt handlande och formens gestaltande ur begrundan.

Att den föreliggande bildsamlingen har hämtats enbart från detta landskap har blivit en naturlig följd av den trots mångfalden samlade karaktär, som Skåne besitter. Man finner de från en svunnen epok bevarade monumenten så tätt, att man ofta inte behöver förflytta sig mer än några kilometer för att komma från det ena till det andra. Till vissa delar skiljer sig detta monumentbestånd från vad som återfinnes inom andra delar av Norden, men i sin helhetskaraktär ger det från ett centralt och begränsat område en synnerligen representativ bild av den romanska nordiska stenskulpturen. I tid omspänner den presenterade skulpturen endast något mer än hundra år, från omkring 1100 till ett stycke in på 1200-talet.

Vikingatiden och den äldsta medeltiden ägde förvisso en inhemsk monumental stenkonst, men dess helhetskaraktär och funktion var väsensskild från den romanska kyrkokonstens. Dennas stenskulptur utgick från helt nya förutsättningar. Den var bunden till kyrkorna och formellt legitimerad genom sin anknytning till de föreställningar, som hörde den kristna kyrkan till. Detta förhållande utesluter emellertid ej, att mycket gick i arv. Bilderna tillkom nämligen under en tid då den kristna föreställningsvärlden ännu var relativt ny i Norden. Samtidigt torde för den enskilda människan och hennes syn på tingen och bilden omställningen från gammalt till nytt ej ha varit alltför stor. Hon levde fortfarande i en handgriplig kontakt med verkligheten i vilken även bilden utgjorde ett påtagligt gestaltande. Men denna verklighet var ej i första hand inskränkt till det mätbara i identitet med den naturliga formen. Den var en spegling av det ogripbara och en upplevelse av hennes eget liv i och som uttryck för den kontrast- fyllda kombinationen av krass realism och övernaturligt beroende.

Skåne var under medeltiden det viktigaste landskapet bland de östdanska provinserna. Redan tidigt efter det danska rikets tillblivelse under 8oo-och 900-talen insåg konungarna vikten av att kunna dominera landskapet. Ett stycke in på 1000-talet grundlade Knut den Store staden Lund. Detta skedde av ekonomiskt politiska skäl för att här kunna draga nytta av handeln och kontrollera de viktigaste vägförbindelserna i anslutning till en av landskapets största marknadsplatser. Ett myntverk växte fram i staden och en rad hantverkare och handelsmän samlades där. Det var under en tid då större delen av Skånes befolkning ännu måste ha varit hednisk. Så småningom började kristendomen få fotfäste i landskapet i synnerhet i Lund, där man får antaga att konungen redan tidigt låtit uppföra en träkyrka. De missionärer och biskopar, som då verkade i landskapet, kom till största delen från England, den västligaste delen av kung Knuts nordsjövälde.

Man kan nog räkna med att Knuts intresse för Skåne och Lund kan ha dikterats av hans planer på att göra landskapet till ett centralområde för det hela Norden omfattande välde, som han strävade efter att foga till sitt dansk-engelska rike. Planerna blev emellertid aldrig tillfullo förverkligade, icke minst på grund av den kompromiss i fråga om den danska kyrkans lydställning under Hamburg-Bremen, som blev resultatet av Knuts sammanträffande med påven och den tyske kejsaren, Konrad II, vid hans besök i Rom 1027. Kungens första initiativ kan dock ha haft grundläggande betydelse för en fortsatt utveckling av Skånes ställning som en så maktpolitisk stödjepunkt i den danska rikspolitiken, främst så länge konungarnas och kyrkans strävanden gick hand i hand.

Redan Knut den Stores fader, Sven Tveskägg, hade lagt grunden till skånska godsförvärv, vilka i synnerhet Knuts syster Estrid vidareutvecklade och kan ha tagit sin tillflykt till. Här kan hennes son, Sven Estridsen, också tänkas ha vistats vissa perioder inte blott under sin ungdom utan även sedan han blivit konung. Som sådan återupptog han den tidigare kampen om den danska kyrkans frigörelse från det tyska ärkepiskopatet. När Sven Estridsen inrättade två biskopssäten i Skåne 1060, kom det ena, i Lund, att besättas av en engelsman i överensstämmelse med de allmänna strävandena. Det andra biskopssätet, i Dalby strax intill Lund, besattes däremot med en tysk, Egino, som emellertid efter sex år flyttade till Lund, sedan den förste biskopen där dött.

Biskopssätet i Dalby nedlades och den påbörjade stenkyrkan har sannolikt inte fullbordats förrän efteråt. Resterna av den äldsta byggnaden, den första kända stenkyrkan i Skåne, förbryllar något med tanke på initiativtagaren Sven Estridsens politiska intentioner. Den kärva men av religiöst-maktpolitisk karaktär präglade pelarbasilikan var av tysk typ med idémässiga förutsättningar i den ottonska byggnadskonsten. Stod den som ett uttryck för kungens eftergift åt det Hamburg-Bremenska ärkestiftet eller representerade den en synlig manifestation av Svens höghetssträvanden gentemot den tyske kejsaren och den tyska kyrkan understruket genom användandet av motståndarens egna maktsymboler? Med tanke på kungens fortsatta omtanke om kyrkan, även sedan den mist sin biskop och blivit kanikkyrka, synes det senare alternativet vara det troligaste.

Enligt Adam av Bremen skulle Skåne redan på 1070-talet ha haft omkring 300 kyrkor. Huruvida detta antal är riktigt eller blott ett resultat av sagesmännens önskan att imponera är omöjligt att avgöra — Adam var i Danmark men sannolikt ej i Skåne. De kyrkor som fanns torde emellertid alla ha varit uppförda i trä. Men efter de två biskopskyrkornas tillkomst har sannolikt även andra stenkyrkor efterhand börjat uppföras. Varken från den äldsta kyrkan i Dalby eller den endast arkeologiskt kända första biskopskyrkan i Lund har bevarats någon bildskulptur.

Ordet Lund har för många blivit liktydigt med dess domkyrka. När denna under 1100-talets förra hälft utan någon konkurrens reste sig över allt vad staden i övrigt kunde bjuda av bebyggelse, måste namnet än mer ha inneburit ett begrepp för kyrkobyggnaden och vad den representerade. Det torde knappast ha varit självklart, att Nordens kyrkliga centrum skulle förläggas till Lund. Staden synes visserligen ha utvecklats gynnsamt, sedan den på 1020-talet grundlagts av Knut den Store, men den låg trots allt i periferien av det danska riket. Redan kung Knut synes emellertid ha fäst stort avseende vid sin nyskapelse, som främst i sin latinska form namnmässigt lätt kunde förväxlas med konungens största stad i den västra delen av hans välde, nämligen London. Bland de många platser där Knut lät sätta igång den första inhemska danska myntpräglingen har Lund intagit den utan jämförelse främsta platsen. Ej heller de följande konungarna lät produktionen sjunka vid stadens myntverk, som sannolikt legat i nära anslutning till kungsgården.

Om Lund sålunda synes ha varit stadd i en kraftig ekonomisk utveckling under större delen av 1000-talet, har staden emellertid inte i kyrkligt hänseende under denna tid kunnat hävda sig gentemot vissa östdanska städer. Någon egen biskop fick Skåne inte förrän 1060, och när Knut den Stores syster Estrid omkring 1030 byggde en stenkyrka i Roskilde, vilken senare ombyggdes till en större av biskop Svend på 1070-talet, hade man i Lund fortfarande blott stavkyrkor att tillgå. Förhållandena ändrades återigen på kungligt initiativ. På 1080-talet lät Knut II, sedermera den Helige, bygga sig en stenkyrka helgad åt S:t Laurentius. Den påbörjades sannolikt som kunglig gårdskyrka, men kungen överlät den åt biskopen och det domkapitel, som kunde komma till stånd genom hans generösa donationer till kyrkan.

Gynnade av påvestolens motsatsställning till de tyska kejsarna lyckades det slutligen konung Erik Ejegod och lundabisko- pen Ascer att med gemensamma ansträngningar lösgöra den danska kyrkan från Hamburg-Bremens överhöghet. Detta skedde under de allra första åren av 1100-talet, och 1104 kunde Ascer beklädas med palliet. Han blev därmed inte blott ärkebiskop i Danmark utan även primas över hela Norden. Det är med stor sannolikhet bland annat på grund av denna redan från början eftersträvade institutionella värdighet och den därmed ernådda maktställningen som ärkebiskopssätet förlades till Lund i Skåne, den del av Danmark som hade det mest centrala läget med hänsyn till kontakterna med och kontrollen av den skandinaviska halvön. Det var i kyrkligt maktpolitiskt hänseende samma drag, som Knut den Store i allmänpolitiskt syfte hade gjort knappa hundra år tidigare, när staden Lund grundades. När Saxo Grammaticus i slutet av seklet skulle motivera varför Lund valdes som ärkesäte anförde han bl.a., att »från angränsande områden kommer man med lätthet dit. Vägarna är många till lands och till vatten».

Ärkebiskop Ascer härstammade från en av de danska stormannaät- ter av bondesläkt, ur vilka såväl konungar som biskopar rekryterades. De kärva dragen hos dessa män får en monumental återspegling i de tidigaste delarna av Lunds domkyrka, för vilken de första impulserna hämtats från traditionellt västeuropeiskt håll. Det mäktiga kryptrummets äldsta delar är i sig självt skulpturalt gestaltande, bilden saknas, de konkreta symbolgestaltningarna är som i sanktuariets kolonner ännu blott ornamentalt uttryckta.

Med den betydelse som Lund fick genom ärkesätets inrättande kom Skånes historia i något mer än hundra år, d.v.s. just den tid som det här presenterade bildmaterialet omspänner, att i stora stycken bli dess biskopars. På väsentliga punkter känner vi denna historia genom det skrivna källmaterialet. Men även tingen, och till dessa hör den skulpturala världen, är en form av källmaterial för kunskapen om den enskilda människans uppfattning av sin tillvaro. Innan vi försöker utläsa något härav, skall dock en del av den mera gripbara situationen tecknas.

År 1137 efterträddes Ascer på ärkebiskopstronen av Eskil. Han synes ha varit en man av helt annat slag än sin föregångare. Eskil var visserligen brorson till denne, men i motsats till Ascer, som i huvudsak hade varit inriktad mot det maritima Västeuropa, hade Eskil en synnerligen livlig kontakt med det kontinentala Europa. Med Bernhard av Clairvaux var han nära vän, och när Eskil efter ett i många stycken dramatiskt liv på 1170-talet avsäger sig sin ärkebiskopsvärdighet reser han till Clairvaux, där han 1182 ändar sitt liv. Den politiska historien i Danmark under Eskils tid var synnerligen förvirrad på grund av de ständiga stridigheterna mellan växlande tronpretendenter med sinsemellan nära släktskap. Kyrkans förhållande till kungamakten hade tidigare varit gott. Eskil var europé även i det avseendet att han som person kom att taga del i tidens stora tvister mellan stat och kyrka. I sina visserligen försiktiga men dock försök att även i Danmark hävda kyrkans oberoende ställning blev han gång på gång inblandad i de politiska stridigheterna kring kungarna.

Men till trots av de oroliga tiderna utvecklades genom Eskils personliga initiativ en ny och fruktbar kulturpolitik, som lade grunden till icke minst ett Skåne i den europeiska gemenskapen. Domkyrkan fullbordades i ett nytt byggnadsskede, som förde med sig en rik skulptural utsmyckning, och 1145 kunde högaltaret invigas. För utbredandet av kristendomens kulturella frukter spelade klosterväsendet i dess olika former kanske den mest framträdande rollen. Som klosterstiftare har Eskil icke kunnat överträffas av någon annan dansk biskop. Före hans tid fanns i Skåne blott ett benediktinkloster i Lund och det i början av 1100-talet av augustinerkorherrarna övertagna Dalby. I självklar överensstämmelse med sin vänskap till Frankrike och Bernhard av Clairvaux införde ärkebiskopen cistercienserna i landet och det första klostret grundades 1144 i Herrevad i Skåne. Det blev emellertid en annan orden, som Eskil främst i Skåne kom att gynna, nämligen premonstratenserna. Ej mindre än fyra kloster av denna orden lät han växa fram, i Tommarp, Öved, Lund och Vä. Det hade säkerligen stor betydelse, att premonstratenserna liksom cistercienserna vid sidan om sin andliga verksamhet också hade en praktisk inriktning, men därtill kom för premonstraten- serklostrens vidkommande att de kunde placeras i en stad. Så blev fallet icke blott i Lund utan även i Tommarp och Vä. Kännetecknande för denna ordens kloster var även att de lydde direkt under biskopen, vilket kan ha haft en alldeles speciell betydelse med tanke på att Eskil placerade dem på några av de ekonomiskt sett mest strategiska platserna i landskapet, d.v.s. i anslutning till de städer, där även kungamakten hade intressen att försvara i sin kontroll över det ekonomiska livet.

Med ärkebiskop Eskil kom Lund och Skåne i direkt förbindelse med den franska kulturen. Det skedde icke blott genom Eskils personliga relationer och resor till Frankrike utan också genom de nygrundade ordnar, som utgick därifrån. Den en gång upprättade kontakten fortsatte under de följande biskoparna, och de franska kulturinflytelserna blev vid sidan av det äldre arvet av väsentlig betydelse för det sena 1100-talets intellektuella blomst- ring.

Lundastiftets fyra första och mest betydande ärkebiskopar var sinsemellan ganska olika typer med var och en sina framträdande drag. Ascer synes ha varit den trygge och utan åthävor kraftfulle man, som med sin person förmedlade det gamla arvet till den inbrytande nya tiden. Eskil var den store kyrklige nydanaren med de vida förbindelserna. Hans efterträdare från 1179, Absalon, var i första hand politiker såväl på det kyrkliga planet som icke minst på det allmänpolitiska. I motsats till Eskil stod han i direkt vänskapligt förhållande till kungamakten, som genom kung Valdemar I hade stabiliserats redan i slutet av Eskils biskopstid.

Som minister hos konungen sysslade Absalon tidvis i högre grad med rikets politik och militära fälttåg mot venderna i Östersjön än med kyrkans angelägenheter. Det är från hans tid, de skånska problemen börjar framträda mera konkret. Tillkomsten av en lång rad betydande institutioner i Skåne såsom ärkesätet, klosterstiftelserna och även städernas utveckling, hade självfallet betytt en stor tillgång för landskapet. Men initiativtagarna hade kanske inte alltid blott landskapets bästa för ögonen. I själva institutionerna som sådana låg en framträdande möjlighet till makt och behärskning av ett synnerligen åtråvärt landskap.

Av alla de män, vilka vi känner till namnet, och som hittills på ett mera framträdande sätt hade varit verksamma inom Skåne, var ingen född skåning. De härstammade antingen från Jylland eller, vilket i synnerhet under Absalons och kung Valdemars tid var fallet, från Själland. Under Absalons tid kom också en skånsk animositet gentemot det själlandska styret direkt till uttryck. Det skedde i samband med en sammandrabbning mellan å ena sidan ärkebiskopens och konungens folk och å den andra de skånska bönderna i början av 1180-talet. Anledningarna härtill var flera. Man kan från skånsk sida skymta ett missnöje med de ständiga ledungsutskrivningarna för vendertågen, vidare knotade man över biskopstionden och Absalons krav på prästernas celibat. Samtliga ting hade haft aktualitet redan under Eskils tid, men han hade gått försiktigt fram och för övrigt ej heller haft stöd av en stark kungamakt. De nya och bryskt ställda kraven fick de skånska stormännen och bönderna att resa sig. Dessa skånska storbönder synes ha varit av delvis annat slag än de västdanska. De hade ännu inte nått samma ryktbarhet och framträdande ställning inom den danska rikspolitiken som t.ex. de själländska Hvideättlingarna. De skånska storbönderna torde i betydligt längre tid ha levat kvar i senvikingatida traditioner och värnat sin egen lokala frihet. Tillgångarna från de runt om i landskapet utplanterade internationella kulturinstitutionerna hade de däremot med sund beräkning tillgodogjort sig, var och en inom sitt område. Ett sådant, visserligen hypotetiskt men dock sannolikt läge, kan vara en av förklaringarna till den sällsynta på en gång jämnt utspridda men samtidigt till karaktären differentierade kulturmanifestation, av vilken epokens skulptur är en del.

De skånska bönderna fick till det yttre se sig besegrade, men de blev aldrig kuvade. De själländska herrarna kunde dock fortsätta att i landskapet uppföra nya kyrkor och med tillhörande bilder berika provinsen och samtidigt också manifestera sina anspråk. När mordet på Thomas Becket endast ett tjugotal år efter det att det ägt rum framställdes på en skånsk dopfunt, är det sannolikt ej blott helgonet som sådant som förhärligas utan även biskopen med de rättmätiga kraven. Eftersom dopfunten befinner sig i en kyrka, Lyngsjö, som i flera avseenden synes vara uppförd av en man i den själländska släkt till vilken ärkebiskopen hörde, synes Absalons medvetenhet ligga i öppen dager. Hans medverkan till ett annat kyrkobygge i samma trakt, N. Åsum, har dokumenterats på gammalt vis med en runsten rest vid kyrkan.

Visserligen fick skåningarna handgripligen känna på Absalons regemente, och visserligen var han i första hand rikspolitiker, men som sådan lyckades han under konungarna Valdemar I och dennes son Knut VI åstadkomma ett fruktbart samarbete mellan kyrkan och staten, ett samarbete som genom ärkestiftet i längden även kom Skåne till godo. Icke blott ärkebiskopen och de enskilda stormännen utan även bönderna i sockengemenskapen synes under denna tid ha bedrivit en mycket livlig kyrkobyggnadsverk- samhet, d.v.s. ett ersättande av de gamla träkyrkorna med stenkyrkor, vilket tyder på att landskapet under denna period gynnats av en växande ekonomisk utveckling. Den direkta andliga odlingen hade emellertid ej missgynnats av Absalon, även om han inte fortsatte sin företrädares intensiva klosterstiftande. Ett betydande kloster grundlade Absalon dock i Skåne, nämligen benediktiner- nunneklostret i Bosjö. För övrigt åstadkom han en reformering och uniformering av den danska kyrkan.

När Absalon dog 1201 efterträddes han av Andreas Sunesen. Denne den siste i raden av lundastiftets fyra första och stora ärkebiskopar har gått till historien som den lärdaste av de fyra. Grunden hade han lagt under studier i Paris, Bologna och Oxford. För att bibringa de blivande präster, som fick sin utbildning i Lund, något av de kunskaper, som kunde inhämtas vid de utländska universiteten, författade han en stor lärodikt på hexameter. Med skapelseberättelsen som kontrapunktiskt motiv skildrades och kommenterades i denna den kristna frälsningshistorien. Andreas Sunesens juridiska bildning, inhämtad i Bologna, blev till stort gagn i en viktig omredigering och kommentar till skånelagen, genom vilken vi får en konkret bild av den skånske bondens liv.

Under slutskedet av Andreas Sunesens ärkepiskopat kom en ny klosterorden till Skåne. Redan 1223 uppläts plats för dominikaner- na i Lund, varifrån de sedan spred sig till andra städer. Införandet av skilda klosterordnar kan under dessa tider ses som ett slags spegling av de expanderande kulturinflytelserna och de genom den samhälleliga utvecklingen uppkomna behoven. Tiggarmunkarnas ankomst står här som slutet på den epok, som vi ägnar vårt intresse. Deras närvaro betydde, att man hade nått fram till ett utvecklat stadsväsende. Grunden härför var i Skåne lagd redan 200 år tidigare med Lund, som senare under 1000-talet följdes av andra inlandsstäder som Tommarp och Vä samt Hälsingborg vid sundets smalaste del. Under 1100-talets ekonomiskt-politiska förhållanden började nya kuststäder växa fram och få betydelse ej blott för landskapets inre handel utan även för den yttre.

Bland dessa kom Skanör och Falsterbo, belägna på ett näs längst ut åt sydväst, att intaga en speciell ställning, till en början och huvudsakligen ej som direkta stadsbildningar, eftersom livet här var relativt säsongbetonat, utan som stor internationell marknadsplats i den viktiga handeln med sill. Under ett par månader årligen samlades här handelsmän för att mottaga den längs skånekusten så riktligt förekommande varan i utbyte mot egna produkter. Bland de köpenskapsidkande utlänningarna kom från slutet av 1100-talet tyskarna från det nybildade Hansaförbundet att bli i majoritet. Tyska impulser påverkade också i icke ringa grad utvecklingen mot det organiserade stadsväsende, som blev karakteristiskt för högmedeltiden, och som i Skåne tog sin början under förra hälften av 1200-talet.

Med vad dessa städer och deras borgerskap kom att representera infördes något nytt i samhällslivet vid sidan om det gamla bondesamhället. Men allt detta hade förberetts under det föregående seklet, som just genom att vara en nydaningsperiod, stadd i ständig utveckling, i alla avseenden kom att både ekonomiskt och kulturellt bli en av Skånes främsta storhetstider. I grunden hade utvecklingen burits upp av det gamla bondesamhället, som trots starka inflytelser från kontinenten aldrig utvecklades till ett feodalsamhälle. De fria bönderna hade känt sig av samma ätt som herrarna, och frihetsmedvetandet, som en gång kanske yttrat sig i självsvåld, hade under kristna institutioners inflytande fått en ny inriktning och ett nytt ansvar.

I sitt förhållande till verkligheten och de ting och bilder, som speglade denna, torde detta samhälles människor haft en mera ohämmad och mindre formalt bunden inställning än vad som skulle följa i det kommande mera borgerliga samhället. Beroendet av tingen, ej av markens växt i den sig rytmiskt förändrande naturen, kom för borgaren så småningom att medföra, att han föredrog att se sig själv och sin omgivning avbildad enligt den verklighetsbild, som var entydigt gripbar. Den föregående expansiva tidsåldern band vanligtvis ej föreställningarna av den sinnliga verkligheten i en accepterad eller given form. Därigenom kunde i dess bildkonst den aktuella föreställningsvärlden infångas i en skiftande mångfald, som speglar såväl djup andlighet som naiv rättframhet.

Det var inom och i anslutning till kyrkan som huvudparten av den monumentala bildkonsten tillkom under hela medeltiden. Detta är i synnerhet giltigt för den äldre delen av epoken, som också är aktuell i detta sammanhang. Den förbindande länk med en äldre och förkristen tradition, som kan och bör ha funnits i t.ex. skulpterade delar av de gamla träkyrkorna, har för Skånes vidkommande på ett undantag när gått helt till spillo. Det blir alltså med de nya stenkyrkobyggena, som den skulpterade bilden framträder. De utan jämförelse flesta av dessa kyrkor uppfördes i Skåne under 1100-talet och är än i dag bevarade i hundratal.

Att vid denna tid uppföra en stenkyrka torde ha varit ganska kostsamt. Det bör heller icke råda något tvivel om, att de första och även i fortsättningen viktigaste initiativen utgick från de stormän, som satt inne med de ekonomiska möjligheterna. Dessa betraktade sig då som i någon mån ägare av själva kyrkobyggnaden men samtidigt också som patronus och försvarade av densamma. Denna byggnadens ägorättsliga ställning manifesterades ofta genom de kraftiga västtorn som lika mycket var symbolen för makt som praktiska byggnadsdelar, i vilka bl.a. patronus särskilda loge inrymdes. Men vi kan också av själva byggnadernas utformning konstatera, att även församlingens bönder redan tidigt själva började uppföra sina kyrkor. Kyrkobyggandet såväl som den skulpturala utsmyckning gynnades i väsentlig grad av att Skåne äger en rik naturlig tillgång på ädelt stenmaterial i de redan från 1000-talet utnyttjade sand- och kalkstensbrotten. Det är nästan uteslutande i detta material, främst sandsten, som de presenterade skulpturerna är utförda.

Stenmästarna

Vilka mästarna till Skånes många stenskulpturer var eller var de kom från har vi inga direkta uppgifter om. Att de ledande skulptörerna vid domkyrkan hämtats från Sydeuropa, sannolikt Italien, bör det ej råda något tvivel om. Men därför finns det ingen an- anledning att tro, att de stenmästare, som berikat landskyrkorna, annat än i undantagsfall skulle ha hämtats från främmande land. Här såväl som i andra delar av Europa var huvudparten av skulptörerna under i varje fall den tidigare delen av medeltiden anonyma. Det finns emellertid alltid undantag, och så var också fallet bland de skånska stenmästarna. På tympanonfältet över ingången till Ö. Herrestads kyrka kan man ännu tydligt läsa orden: »Carl stenmester skar thenna sten.» Man har allmänt antagit, att denne Carl stenmästare skulpterade inte blott den sten, på vilken inskriften återfinns utan även portalomfattningen som helhet. Utifrån den kring portalen förekommande skulpturala ornamen- tiken har man sedan sammanställt en lång rad skulpturer i framför allt sydöstra Skåne men också i landskapets mellersta delar, skulpturer som ansetts utförda av denne Carl. Även om inte allt som tillskrivits Carl kan anses vara utfört av honom, har vi dock genom signaturen ett vittnesbörd om en stenmästare av säkerligen nordisk och väl skånsk härkomst. Att han fått fästa sitt namn vid ett av verken tyder kanske på, att han haft en lokal berömmelse och åtnjutit ett anseende, som förmodligen inte alltid kom ens den skickligaste konstnär eller hantverkare till del under denna tid.

Carl stenmästares signatur har återfunnits endast en gång, men det fanns ungefär vid samma tid under 1100-talets senare del också en annan skånsk skulptör, som signerat en hel rad dopfuntar. På kuppans kant har han med runor ristat: »Mårten (Martin) gjorde mig.« Många av de dopfuntar, som med hjälp av signaturen eller på stilistisk väg kan hänföras till honom, har kuppan oftast blott ornamentalt skulpterad, men den vilar i många fall på för Mårten karakteristiska lejonfigurer. Att runorna kommit till användning i inskriften är i och för sig ingen ovanlighet. Det var genom hela medeltiden i många fall den skrivkunnige lekmannens normala skrift i första hand för kortare meddelanden eller anrop. Detta utesluter dock ej, att runorna samtidigt av tradition kan ha tillagts en viss magisk betydelse. När Lunds domkyrkas restaura- tor, Adam van Duren, så sent som i början av 1500-talet inleder en av sina många i domkyrkan inhuggna inskrifter med orden »Gud hjälp», är dessa två ord men endast de utförda i runor.

Mårtens signatur på dopfuntarna kan ha varit av samma betydelse som Carls signatur, men det torde ej vara osannolikt, att han kanske i främsta rummet med de magiska runornas hjälp velat fästa en åkallan vid det icke minst för denna tid viktiga sakramentala funktionsobjekt, som dopfunten utgjorde. Det är i sammanhanget icke heller oväsentligt, att det genom formuleringen är föremålet, funten, som talar. Stenmästaren kan ha lagt något av sin själ i verket, för att det inför kommande släkten i förbindelse med dopets sakrament skulle minna om honom.

Den tredje i raden av till namnet kända skånska stenmästare hette Tove. Han har liksom i förbigående smugit in sitt namn bland de texter, som beledsagar framställningarna på dopfunten i Gumlösa. Hans arbeten bör ha utförts under i huvudsak 1190- talet. Därmed är också vår kunskap slut rörande namnen på skånska stenmästare från romansk tid. De har var och en låtit sina namn framstå på olika sätt, kanske av skilda bevekelsegrunder. Ett har de emellertid gemensamt, nämligen de nordiska namnen, som klart utsäger, att det nu var landets egna konstnärer, som flitigast hjälpte till att med sina skulpturer icke blott pryda utan även ge en symbolisk mening åt landskapets sockenkyrkor. Vid en genomgång av bilderna finner läsaren snart, att de flesta återger dopfuntar eller detaljer därav. Denna till synes kvantitativa övervikt för en bestämd föremålsgrupp är inte tillfällig. På den skånska landsbygden manifesteras den rikaste och i flera avseenden mest intressanta tidigmedeltida stenkonsten i första hand på funtarna. Det lär väl icke heller finnas något land i Europa där inom ett bestämt område en sådan myckenhet av romanska dopfuntar bevarats som i Skåne och på Gotland.

Vi kan konstatera, att det funnits verkstäder, som producerat en lång rad likartade funtar, men väl så påtagligt är trots detta mångfalden av de skiftande typer, som man stöter på. De skvallrar om en obunden verksamhet med skiftande impulser, samtidigt som de är i besittning av en påfallande originalitet i förhållande till beståndet från det övriga Europa. Denna originalitet yppar sig inte blott i formerna utan även i den mångskiftande och rika bildvärld, som vi möter på dem.

Ur konsthistorisk synpunkt har man klarlagt vad som avses med begreppet romansk stil. Det råder inget tvivel om att den här presenterade skånska stenskulpturen tillhör denna stilgrupp. Den skiljer sig emellertid samtidigt från mycket av den bildkonst, som från samma epok återfinnes på annat håll och är därigenom lätt igenkännlig om den påträffas exporterad utanför Skånes egna gränser. Paradoxalt nog är det emellertid ej ett gemensamt skånskt stildrag, som gör det starkaste intrycket, utan de påtagliga stilistiska skillnaderna mellan de olika skånska stenmästarna och verkstäderna. Det är i denna mångfald, som den konstnärliga rikedomen ligger. Det är anmärkningsvärt i hur hög grad den enskilde mästaren här självständigt och naturligt har funnit sig tillrätta med både ämne och form, medan man på andra håll då och då kan finna hur denna konst kan ha fått en viss stereotyp prägel. Om den skånska romanska stenskulpturen uppvisar ett eget ansikte är det främst i denna variationsrikedom, som ger den dess säregna plats inom epokens europeiska konst. Tekniken och icke minst hantverksskickligheten spelade en stor roll för den medeltida konstutövningen, den ligger också som grund för en rad av de här presenterade arbetena, men det är dock genomgående främst konstnären bakom verken, som fått dem att tala till oss. Den aktuella mottagligheten härav kan i någon mån ha sin grund i vår tids personlighetspräglade konstuppfattning, men endast som inledningen till en bekantskap; ytterst och med större giltighet är det ödmjukheten bakom skapandet, som får upplevelsen av bilderna att bli verklighet.

Stenskulpturen har av naturliga skäl i motsats till konstföremål av förgängligare material haft större möjlighet att bli bevarade till våra dagar. Detta hindrar emellertid ej, att vad vi i dag ännu kan beundra och njuta av endast är en del av vad som en gång funnits. Under själva medeltiden synes man i stor utsträckning ha tagit tillvara äldre skulpturer i samband med ombyggnader av de partier i vilka bilderna ursprungligen varit placerade. De har insatts i ett senare murverk, kanske mist sin ursprungliga symboliska funktion men möjligen fått en ny sådan, men framför allt torde de ha uppskattats som bild. Vad reformationen i Norden innebar för bildkonsten i kyrkorna vet vi ännu ej tillräckligt om. Den torde för gemene man emellertid ej ha varit en alltför stor omställning i förhållandet till tingen och bilden. På något undantag när förskonades också Skåne från det bildstormande, som gick så härjande fram på vissa håll över Europa. Mera ödesdigert för de medeltida kyrkorna och deras inventarier blev 1700-talet och en stor del av 1800-talet. Under sistnämnda århundrade blev välståndet och rikedomen i vissa bygder en direkt anledning till medeltidskyrkornas förstörelse i samband med att man byggde nya och större kyrkor. Många skulpturer förskingrades under denna tid, dopfuntar användes till blomsterkrukor i trädgårdar, andra skulpturer försvann helt, men en del blev liggande på undanskymda ställen. Därifrån hämtades de i början av detta sekel, när en ny förståelse och ett nytt intresse började vakna för de gamla klenoderna. Vad som då hopsamlades från förstörda kyrkor i Skåne bevaras i dag i Lunds universitets historiska museum. I dag är ej blott de skulpturer som bevaras på museet utan allt som finns i anslutning till de ännu levande gamla kyrkorna skyddat genom fornminne slagen.

BILDVÄRLDEN

Den moderna människans attityd gentemot konst skulle med all säkerhet ha varit den medeltida betraktaren helt främmande. Därmed inte sagt att det vi kallar en estetisk upplevelse i och för sig kan ha varit utesluten. Men den har av medeltidsmänniskan ej medvetet uppfattats som ett isolerat egenvärde. Konstens värde var å ena sidan förknippat med den art av hantverksskicklighet med vilken verket var utfört och å den andra sidan med graden av levandegörande och den förmåga till upplevelse, som bilden kunde väcka. Den estetiska normen har under sådana omständigheter ej någon formal karaktär utan ingår som ett led i verkets gestaltande av det uttryck, som skulle vara ett levandegörande av människans situation i nuet och i evigheten.

Huvudparten av den romanska stenkonst som vi här finner skall därför i första hand upplevas som mer eller mindre talande uttryck för den dåtida människans förhållning till och uppfattning av den omedelbara verklighet i vilken hon levde. Vi kommer att möta en på en gång mångtydig och rakt på sak utförd berättarkonst i skiftande former, ibland obunden och naivt omedelbar och ibland tuktad och ansträngt sirlig i sin strävan att vara det dock existerande modet till lags. Samtidigt måste vi vara medvetna om att ingenting tillkom blott på lek, ingenting utfördes för sin egen skull eller som utlopp enbart för stenhuggarens vilja att manifestera ett formande. Även det enkla och naiva hade för dåtiden en mening, som i sin omedelbarhet talar även till oss och därigenom utgör bevis för anspråkslöshetens möjligheter att finna och gestalta ett uttryck för känsla och upplevelse. Låt oss försöka, i den mån vi kan göra oss fria från normativa form- och uttryckmönster, att till en början betrakta bilden sådan den i sig själv framträder för att alltjämt förmedla den verklighetsupplevelse, som hade giltighet då men existentiellt även nu.

Hos människogestalten möter vi ofta ett drag av sorgmodigt allvar. Som ett slags manande grunddrag kommer detta i första hand till uttryck genom Kristusbilden. Detta allvar kan i den kraftigt stiliserade formen kännas som en genomträngande höghet eller som en något trumpen stränghet. Vi fångas av denna skulpturens direkta talan till oss främst genom de bilder i vilka Kristus tronar och med ögonen fixerar åskådaren. I framställningar av dopet däremot är Kristus visserligen frontalt riktad mot oss men är samtidigt på ett egendomligt sätt passiv gentemot åskådaren och även den handling som försiggår, eftersom det är handlingen som helhet som har betydelse. Ett märkligt undantag finner vi i en dopscen, i vilken Johannes döparen för ett ögonblick glömsk av sitt heliga värv förvånat stirrar på betraktaren ej blitt vädjande utan med en ohämmad nyfikenhet, som även smittat av sig på Kristus. Han har därigenom brutit sin isolering gentemot betraktaren, ej för att mana honom till sig utan för att förundras över hans närvaro. Som förutsättning för denna vår tolkning av scenen ligger med all säkerhet ingen medvetenhet hos den stenmästare, som utfört bilden. Det torde snarare vara det enkla och mänskligt omedelbara i hans uppfattning av händelsen, som får oss att uppleva denna verkan. På samma dopfunt förekommer en framställning av de heliga tre konungarna, vilka på samma sätt synes vara mera intresserade av oss än av det barn de skrider fram för att hylla.

Kontakten mellan å ena sidan gestalten eller scenen och å den andra åskådaren har sålunda åstadkommits med olika uttrycksmedel men är för det mesta påtagligt för handen. När en person vill rikta vår uppmärksamhet på sig eller det han vill säga, sker det oftast genom en gest eller medelst de stort uppspärrade ögonen, som inte vill låta oss undkomma. Men vi finner också exempel på att en intim kontakt kan åstadkommas genom en nästan lättsinnig outgrundlighet avspeglad i ansiktsdragen.

Motsatserna finner vi även i de berättande scenernas handling. En värdig och avmätt högtidlighet möter oss främst i nya testamentets passionsscener men också i lovprisningsscenerna i anslutning till Jesu födelsehistoria, men i själva födelsescenerna blir åskådaren genast mer engagerad. Den betänksamme Josef inbjuder oss under stilla begrundan att taga del av undret i grottan, om ej lika vanvördigt närgående som åsnan och oxen så med den iver och glädje, som präglar herdarna och deras djur.

Direkt in på människorna har vissa stenmästare gått i sin skildring av syndafallet och dess följder. Här möter man den direkta identifikationen mellan åskådare och bildgestalt, utan tvekan en påtaglig upplevelse för den medeltida betraktaren men med adress även till oss, om vi är känsliga nog att uppfatta det. Med en illa dold beräkning mottager Eva frukten av ormen, och Adam sätter tänderna i den med ett hämningslöst nästan djuriskt begär. När paret sedan brukar jorden utanför paradisets trädgård, blickar den trumpne Adam oförstående och frågande på Eva, som med ett halvt vulgärt flin synes vara belåten med den nya situationen. På en annan dopfunt visar hon sig mera sedlig, där hon något uttråkad men stolt sitter med sin slända. Adam däremot är helt nedtyngd inte blott av det snickrande han håller på med utan främst av den bedrövelse, som hans ångerköpta min ger uttryck för.

Kroppen i och för sig har den romanske stenmästaren ej haft något intresse för. När skillnaden mellan de nakna Adam och Eva skall framställas är det ej genom könet utan medelst hårets längd. Klädedräkten kan däremot ofta vara omsorgsfullt utförd, eftersom den i de flesta fall karakteriserar personerna och beträffande statisterna utgöres av tidens egna dräkter, antingen händelserna utspelats för över tusen år sedan, utan bundenhet till tiden, eller i nära anslutning till stenmästarens egen tid. På detta sätt upplevde betraktaren de utspelade händelserna som aktuella och påtagligt närvarande. Men klädedräkten kan också vara fritt gestaltad och genom sin ornamentala form ge ett bestämt ackord som grund för den känslostämning, som gestalten eller scenen avser att avspegla. När den gamle Simeon i templet får se och röra vid Jesusbarnet, präglas figurerna som helhet av en stilla värdighet, men den rörelse, som händelsen uppväcker, kan påtagligt följas i de schematiskt tecknade mjuka vågrörelser, vilka utgående från Marias mantel och över Jesusbarnets svepning blir till en virvel över Simeons vänstra sida. En högtidlighet, ett förvandlande av gestalterna till värdighetstecken för den handling de utför åstadkommer å andra sidan de stora och summariskt skulpterade mantlar, i vilka de tre heliga konungarna är framställda på en dopfunt. På den följande bilden med samma motiv kan man lägga märke till hur skulptörerna vid slutet av epoken med en påträngande vilja till saklig realism och samtidigt en djupare relief i stället åstadkommit en naiv identifiering — det upphöjt allmängiltiga är borta.

Tillsammans med klädedräkten utgör ofta de därunder blott tänkta eller anade kropparna ett rytmiskt ornament för att gestalta en rörelse som hos de tre Mariorna vid Kristi grav. För att framhäva den varma samhörighetskänslan mellan Maria och Elisabeth vid deras möte har skulptören låtit kropparna förenas i en stor form. Här kan vi också se vad som händer när den skulpturala naturalismen ökas, genom avståndet mellan figurerna kan känslogestaltningen iakttagas, men i den tidigare reliefens ut- tryckskonst kännes den.

De par, som på dopfunten i Tryde omfamnar varandra, låter oss förnimma sin samhörighet genom ytterligare ett medel, gesten, som är en av tidens viktigaste uttrycksbärare. De långa och smala armarna, som utförts utan ringaste anspråk på anatomisk sanning, slingrar sig kring gestalterna, binder dem till varandra, samtidigt som händerna endast antyder en öm gest. I arm- och handrörelsernas överdimensionering ligger ofta det dramatiska händelseförloppet samlat. Så är fallet i det händernas samspel, som i en framställning av Adams skapelse betecknar själva skeendet. Gesten kan också vara av rent attributiv karaktär. I en naiv form upplever vi hur en ängel, som satts att vakta porten till det himmelska Jerusalem, med barnslig iver håller fram sin nyckel med en påtagligt förlängd arm.

Det som hos människogestalterna i första hand appelerar till åskådaren är huvudet, oftast förstorat men i sig samlande hela den kraft, som gestalten skall ge uttryck för, vare sig denna kraft är av aktiv karaktär eller fylld av begrundan och allvar. Med ett visst ackompanjemang av händernas gester ligger scenens uttryckskraft i den fig. 217 avbildade nattvardsscenen samlad i ansiktena. Även i den starka stiliseringen förnimmes de skilda karaktärerna och de varierande känslostämningar, som behärskar de agerande. Här liksom i de flesta andra människoskildringarna är det ögonen som mest intensivt förmedlar kontakten såväl mellan de inom bilden agerande gestalterna som mellan dessa och åskådaren. Det sistnämnda gäller även i de fall den formella förenklingen har drivits till sin spets.

Än intensivare träder uttryckskraften i det mänskliga ansiktet oss till mötes, när det isolerat och friskulpterat skjuter fram ur portalernas kapitälräcka eller dopfuntarnas baser. Oftast rör det sig då knappast om en människa längre, även om bilden har fått låna hennes gestalt. Vi står istället inför ett konkret förkroppsligande av de demoner, som satt sig i besittning av människan, och som genom den klart uttalade illsinnigheten i de ilskna ögonen, de gnisslande tänderna och den framskjutna hakan avses skola avvärja det onda, de själv förkroppsligar.

Tygellösheten väller ur den utspärrade käften på den personifierade lasten, liksom den sinnliga vällusten kommer Luxorias ansikte att svälla, när hon diar ormarna. De personifierade lasterna tyglas ej formellt, de förtäres av sin egen lastbarhet. De obestämbara demoner däremot, som i ett obevakat ögonblick kan smyga sig på oss, hålles ofta fast av armar, som drar i ansiktets mustascher, det tvinnade rep, som folktron såg som en magisk fjättra. I formellt hänseende är avståndet ej så stort mellan den avgudabild, som en gång på kyrkans mur har avvärjt de onda anslagen från sina hedniska gelikar, och den fromme biskop, som mottagit folket vid ingången till samma kyrka. Men genom den rustika kraften i det mellan axlarna neddragna ansiktet i det ena fallet och den resliga värdigheten i biskopsansiktet i det andra är det dock representanter för två skilda världar, som möter oss. För den samtida betraktaren var dessa båda världar synnerligen verkliga och på en gång närvarande, inte blott sida vid sida utan i- bland också i en och samma gestalt. När människan fått låna sin hamn åt demonen eller djävulen, då växte hennes öron ut som horn.

Men det var främst i odjurens eller fabeldjurens gestalt, som det onda trädde åskådaren till mötes. En tro på djävulskapet bakom tingen torde ha kunnat få en påtaglig konkretisering i mötet med den väldiga käft, som hotfullt sträcker sig mot betraktaren, samtidigt som den slingrande och framåtpiskande stjärten på det ondskefulla monstret ger eftertryck åt den lömska avsikten att sluka en vacklande själ. Djävulen i egen person, när han skall hjälpa Simon Magus att hoppa från tornet, ser i jämförelse med de gestalter han bemäktigat sig nästan löjligt menlös ut. En grotesk figur gör han som fängslad och besegrad, men när han i lejonets eller odjurets gestalt mellan sina väldiga käkar krossar det menlösa lammet eller med ormar som medhjälpare är i färd med att sluka en människa sker det i den kraftfulla skulpturala formen med en sådan intensitet, att han därigenom binder och avvänder sin egen makt men samtidigt utgör ett varningstecken för betraktaren. Med en sneglande blick på sitt hjälplösa offer får han åskådaren att uppleva händelsen inte blott som en engångsföreteelse utan som något som sker nu.

Men inte ens alla odjur behöver vara ondskans bärare. Främst lejonet kan också representera motsatsen, och framför allt får det med sin kraftfulla gestalt förkroppsliga styrkan, när det bär de kolonner på vilka kyrkan vilar. Tränger gruvligheten på oss från de djur, som för människan var okända och farliga, möter vi desto större charm och nästan älsklighet i framställningen av de djur, som människan omgav sig med och som var hennes vänner. I detta avseende intager hästen som den dåtida människans vid många tillfällen oumbärlige tjänare den främsta platsen. De tre vise männen kommer ridande till Betlehem på sina ståtliga fuxar, och när den heliga familjen flydde till Egypten, kunde den nordiske stenmästar- en ej tänka sig att det skulle ha skett på en åsna utan placerade Maria och barnet på en praktfull häst, som värdigt och säkert för dem bort från Herodes mordiska anslag. Den nära samhörigheten mellan hästen och hans herre skildras med för tiden helt ovanlig, nästan lyrisk inlevelse. Bakom den knäböjande Eustachius intager hans häst en elegant följsamhet i sin rörelse, som kommer en att direkt konfronteras med dåtidens synbarligen starka bundenhet till sitt oumbärliga djur. Medkänslan kan i den friare skulpturen taga sig uttryck i en nästan sammansvetsad form mellan ryttare och häst.

Liksom när det gäller hästen är det många gånger påtagligt med vilken noggrannhet tingen är skildrade. Det sker också i nära anslutning till samtidens förhållande. Förekommer ett skepp ansluter det sig med sina djurhuvudsförsedda stävar nära till den inhemska traditionens vikingaskepp. Den händelse skeppet skildrar eller den symboliska funktion det besitter blir på detta sätt mera omedelbart närvarande. Detsamma gäller de tidstypiska dräkterna av både vardagligt, krigiskt, konungsligt eller liturgiskt snitt. De enskilda föremål, som direkt utsäger något om situationens betydelse har man klart framhävt. Sedan Adam och Eva drivits ur paradiset och tvingats till hårt arbete, har Adam fått börja svänga den tunga timmermansyxan och Eva tvinna ullen med sin slända, sysselsättningar med vilka betraktaren var helt förtrogen, och som kom honom eller henne att identifiera sin egen situation med de äldsta förfädernas. Men redskapet har förtydligats även för att stå som tecken för handlingar av mindre vardagligt slag, för handlingar av ingripande betydelse i den kristna frälsningshistorien. Med det lyftade svärdet utsäger kung Herodes sin befallning om barnamordet i Betlehem. Det rep, med vilket Kristus fängslad föres inför Pilatus, framträder med större skärpa och naturtrohet än de agerande gestalternas kroppar. Hammaren och spiket i handen på mannen vid Kristi kors tjänstgör i första hand ej i en konkret handling, Kristus är redan spikad vid korset, ja han är redan död, Longinus har just träffats av det från Kristi sidosår utstrålande vattnet och blodet, hammaren och spiken hålles av en människa vilken som helst, som alltjämt medverkar till Kristi fastnaglande vid korset.

I allt har den romanska stenkonst vi här står inför en mening och betydelse utöver den sakliga skildringen. Själva ornamentiken är icke blott eller kanske ens i första hand prydande utan gestaltar symboliskt översinnliga begrepp. Palmetterna och vinrankorna på dopfuntarnas kuppor erinrar om det livgivande vattnet. Den slutna ringkedjan från ett korskrank är bilden av evigheten i vilken allt är länkat och med vilken livet i palmettens form är förbundet. För säkerhets skull pekar en helig man med en manande gest på den abstrakta bilden samtidigt som hans rakt på oss riktade ögon suger vår uppmärksamhet till sig.

Allt vad den romanske stenskulptören har skildrat har en i vidaste bemärkelse religiös förankring. Förmågan att uppleva den kristendom, som ej hade varit bofast i området mycket mer än hundra år, som en till nuet och tingen bunden verklighet, har sannolikt ej inneburit alltför stora svårigheter för de människor, vilkas ej alltför avlägsna förfäder under hednisk tid stod i ett ofta påtagligt förhållande till de makter de trodde sig se och uppleva i naturen och dess ordningar. Nu hade förtecknen ändrats och den väsentliga inriktningen i människans strävan hade blivit en annan. Men den upplevda kraften av både det godas och det ondas konkreta närvaro var lika kännbar. Vi har sett hur man i enskildheter genom bilden har kunnat ställas i direkt konfrontation med de heliga eller djävulska tingen. I scenerna som helhet var identifikationen ej lika stark, deras syfte var påvisande, berättande, fastställande, men konstnären har ej objektivt frigjort sig från vad han skildrar. I enskildheterna upplever man detta. Med en religiös motivering i sitt bildval har stenmästaren sällan framställt aktuella handlingar. Någon enstaka gång har det skett, som i den dopscen, som förekommer på en funt. Men scenens handling är rent liturgisk och den är direkt bunden till det föremål, som används. Men med scenens närvaro knytes de vid dopet deltagande på ett direkt sätt till den sakramentala handlingen.

Bland bibliska framställningar är det i första hand Adams och Evas historia, framför allt deras arbete, som kan ha haft en identi- fikatorisk verkan på åskådaren. Eljest är det främst de icke bibliska scenerna, som kan ha appelerat till betraktaren och hans egen situation. Icke minst kan detta vara fallet om de lärande scenerna dessutom synas ha anknytning till gamla nordiska värderingar. Uppfattningen av det mer eller mindre ärofulla sättet att dö kan möjligen avspeglas i en svårtolkad scen. På kuppan till en dopfunt finner man på ömse sidor om ett skepp två dödsscener. På den högra sidan en man, som dör djältedöden, martyrdöden, och vars själ av en ängel föres till himlen, på den vänstra sidan en man som synes dö den i den fornnordiska uppfattningen vekliga döden i »sotsäng». Stolpen med vädurshuvudet bakom sängen skvallrar också om att hans själ i form av en liten naken människa inte som i förra fallet föres mot höjden utan till ett nedre dödsrike. En allvarstyngd sorgmodighet präglar de medagerande personerna, men främst den lilla bedrövade själen, som med huvudet på sned vädjar till åskådaren att betänka sitt liv. Tematiskt syftar säkerligen scenerna direkt på bestämda motiv, som för oss har gått förlorade, och som kanske för dåtidens betraktare också var okänt. Men det som händer hade genom sin gruppering i relation till övriga mera klara symboliska framställningar på funten en påtaglig anknytning till en gängse föreställningsvärld.

Gör alla dessa bilder än i dag ett starkt intryck på oss genom att aktivera vår känsla och inbillningskraft, hur mycket intensivare skall de då ej ha verkat på samtidens människor. I deras torftiga vardagsmiljö måste stenskulpturen redan i sig själv ha varit något enormt, och därtill kom att den tjänstgjorde som ett materiellt förkroppsligande av vad många i dag vill kalla idéer och makter, men som medeltidsmänniskan upplevde som verklighet.

Betydelsefunktionen

Det torde vara naturligt, att dopet varit av fundamental betydelse i människornas religiösa uppfattning under en tid, då kristendomen var relativt ung, och då kampen med de hedniska makterna ännu var levande. Häri ser vi förklaringen till att en så rik konstnärlig aktivitet kommit till uttryck i prydandet av de många dopfuntarna med deras skiftande och intensivt engagerande bildvärld. Vi kan svårligen komma ifrån, att många av de hiskliga djuren på funtarnas baser representerar ondskans makter, även om andra funtar på motsvarande ställen kan ha smyckats med himmelska representanter. Den fauna och det liv, som här utvecklar sig för våra blickar, är i många stycken svåra att tyda, och många gestalter kommer kanske att för all framtid ruva på sina hemligheter.

På funtarnas kuppa möter vi till synes mera lättbegripliga framställningar. De är i de flesta fall förståeliga i sina enskildheter, men vi vill veta vad de innerst avser att gestalta.

Alla de scener, som skildrar Jesu dop i floden Jordan, utgör en lättförklarlig framställning av dophandlingens historiska prototyp. I Bjäresjö kyrka möter man däremot en bild av dopet, som går helt utöver den historiska skildringen. Jesus sitter i en kalk- formad dopfunt och håller i sin högra hand ett kors. På hans högra sida står Johannes döparen och på hans vänstra jungfru Maria, som håller något som bör tydas som ett långt vaxljus. Här skildras inte enbart dopet utan även korsdöden och med ljuset, påsknatts- liturgiens tecken, uppståndelsen till det himmelska paradis, som sammanfattas i rosetten ovanför Kristi huvud. Här gäller det ej i första hand att erinra sig en biblisk händelse utan att begrunda ett mysterium — att vi genom dopet skall dö för att återuppstå med Kristus.

Ständigt ställs vi inför denna koncentrerade symbolik i betraktandet av de äldsta medeltida bilderna. Klart och uttrycksfullt rullas skärtorsdagsnattens händelser upp för våra blickar på funten i Löderup, men när skildringen kommer fram till händelsernas kulmen ser vi en bild, som inte längre är berättande i positiv bemärkelse utan som i sig samlat upp en betydelse utöver tid och rum. Korset svävar över Golgata, det bäres i rundlarna av de gestalter, som på en gång representerar de fyra evangelisterna och deras vittnesbörd samt de fyra väsenden, som skall synas tillsammans med Kristus vid hans återkomst. Den enskilda människans delaktighet med Kristus representeras av Longinus, som sedan han med sin lans stuckit upp Kristi sida, träffats av det utströmmande blodet och vattnet — dopets vatten.

På få platser och under få tider har konstnärerna i en omedelbar och värdig form så lyckats återge sin tro på en mystisk samhörighet, formad av den konkreta berättelsen, existentiellt förnummen i den sakramentala samhörigheten och stående under det tecken, som också skall bilda dopets slutliga fullbordan, Kristi återkomst i sitt majestät över den för honom redan beredda tronen.

Den tronande Kristus är ett huvudmotiv, som återfinnes på en rad funtar och visar dopsymbolikens inordning i ett eskatolo- giskt sammanhang. Detta är ett typiskt drag i den äldre medeltidens sakramentala symbolik, vilken ofta låter delar i frälsnings- läran ställas i relation till den omfattande helhet, som bildmässigt gestaltas av Kristi slutliga återkomst. Den möjlighet till uppståndelse, som den döpte kan bli delaktig av vid detta tillfälle, kan vi kanske finna uttryckt genom den person, som på basen till fun- ten i Saxtorp lyfter sina händer mot den Kristusbild, som sannolikt ursprungligen funnits ovanför, men som genom kuppans vrid- ning kommit på annan plats.

Lika vanligt som det är att inom de äldre funtgrupperna finna rikligt med inslag av ofta svårtydbara symboliska framställningar, lika ofta möter man bland de yngre funtarna en till synes enhetligare och mera lättförståelig bildvärld. Detta innebär för visso ej, att bilderna, om de ej är direkta framställningar av dopet, skulle sakna en symbolisk anknytning till detsamma. De ofta förekommande fortlöpande framställningarna ur Jesu födelsehistoria är ett exempel härpå. Säkerligen har bilderna haft till uppgift att vara en direkt erinran om julens mysterier, men deras intima samband med dopfunten bör i första hand ses mot bakgrunden av uppfattningen om dopet som en pånyttfödelse. Denna den enskilda människans pånyttfödelse sker genom delaktighet i Kristus, och på ett enkelt och handgripligt sätt har denna delaktighet med bildens hjälp kunnat förbindas med Jesu egen födelse. På samma sätt kan vi kanske finna den dubbla uppgiften hos de bilder som framställer scener ur skapelseberättelsen. Tidigare har talats om hur inte minst dessa kanske genom sin formala karaktär, genom identifikationen bör ha kunnat åstadkomma en påtaglig kontakt mellan åskådaren och sig själva. Men ytterst borde då denna kontakt leda till ett medvetande om att skapelsen här står som en symbolisk hänsyftning på den skapelse till nytt liv, som dopet verkar.

Men det är icke blott de med figurernas hjälp berättande fun- tarna, som gestaltar de symboliska tankegångar, vilka hänger samman med dopets sakrament. Även de enbart ornamentalt smyckade torde kunna beläggas med sådana hänsyftningar. Palmetter och rosetter har säkerligen kommit till inte enbart för att pryda kupporna. Deras betydelse av det himmelska paradiset har kanske genom konventionen efterhand fallit i glömska, men säkert ursprungligen varit medveten. Ja, kanske det fyrekrade hjul, som vi finner på en funt, är en direkt hänsyftning på de fyra paradisfloderna, vilka i dopsymboliken är direkt förknippade med dopvattnet. I många fall får kanske också de på baserna förekommande fyra djur- eller människohuvudena tydas i denna riktning. Att den skulpturala bildvärlden på funtarnas baser ej alltid gestaltat den besegrade ondskan framgår klart av figurer, vilka är entydiga representanter för framträdande personer i det himmelska paradiset. Vi finner Abraham med de saliga i sitt sköte, Maria som den främsta förebedjerskan inför det barn hon håller i sitt knä samt apostlarna Petrus och Paulus.

Det är emelletid inte blott den teologisk-symboliska djupsinnigheten, som kommer till uttryck i bildvärlden. En kontakt med de mänskliga villkoren kan vi möjligen se upprättad genom de manifesterande framställningarna av delvis »propagandistisk» karaktär. Helgonlegenden i Tryde har möjligen en sådan uppgift i religiöst avseende, mordet på Thomas Becket dessutom med en politisk baktanke samt den under en viss period ofta förekommande framställningen av Petrus i Kristi omedelbara närhet med en religiöst-politisk hänsyftning.

Av denna sällsamma rikedom på motiv och skiftande uttrycks- gestaltning i anslutning till en enda föremålstyp, funten, får vi en antydan om den dåtida uppfattningen om dopet som något oerhört väsentligt. Inte blott med den grundläggande betydelse det har i konventionell kristen uppfattning utan därutöver även som en rent materialiserad sakramental akt, genom vilken hela personen inte endast i andlig utan även i kroppslig bemärkelse blev förenad med Kristus, den nye härskaren, vilken även konungen ägnade sin hyllning och tillbedjan, när honom så lyste.

Kyrkobyggnaden var enligt medeltida uppfattning ej blott en gudstjänstlokal utan en Guds boning, som därigenom blev en symbol för det himmelska Jerusalem. Till detta är Kristus porten, och följaktligen kunde ingången till kyrkan också hänsyfta på Kristus. Det kunde i olika former ske direkt eller med hänvisning till skilda trosföreställningar, som skulle väcka den inträdande till medvetande om ett ställningstagande i kampen för det goda. Det är av denna anledning, som den tidigaste arkitekturskulpturen i första hand utbildas i och kring portalen.

Kring portalerna till många av de kontinentala stora kyrkobyg- gena finner man ofta hela den symboliska dialektiken uttryckt på ett många gånger elegant men ibland nästan kyligt intellektuellt sätt. Men var finner man de centrala kristna mysterierna koncentrerat framställda med sådan enkelhet och omedelbart människonära iver som i tympanonfältet över portalen till den lilla tidigmedeltida kyrkan i Linderöd, i det mellersta Skånes skogstrakter. Mot ett rörligt och till vissa delar kaotiskt myller framträder Kristus som den krönte konungen. Han härskar från det kors, som han står framför. Han är porten, men just på grund av allt det, som utspelar sig kring honom. I det vänstra hörnet finner vi födelsen och i det högra den besegrade satan, besegrad genom korset, från vilket Kristus här uppstår och återkommer för att på den yttersta dagen skilja det onda från det goda. Inför denna eskatologiska vision står betraktaren inför hoppet om att få befinna sig på Kristi högra sida tillsammans med bl. a. den biskop, som återuppstånden frambär sitt lov med den gest, som i mässan ledsagar praefationens lovprisning.

I de flesta fall har tympanonfältet ståtat med en framställning av Kristus mellan apostlafurstarna, Kristus som Agnus Dei eller representerad av sin gammaltestamentliga prototyp Simson, eller också finner man symboliska djurbilder, vilka ej längre synas ha den direkta syftning på portalens betydelse, som ovan anförts. När två gripar på ett tympanon i Gråmanstorp sträcker sig mot ett i mitten stående träd, kan det vara själen, som längtar efter frukterna från livets träd. Över den motsatta portalen i söder har två stora djur med ett koppel bundits vid trädets stam, och från djurens munnar utgår växtrankor. Här har de blivit delaktiga av det livgivande trädet, som från att ursprungligen ha stått i Edens lustgård blivit Kristi kors för att slutligen symbolisera Kristus själv. Denna positiva tydning är ej lika lätt att tillämpa på de vanligen förekommande motiven med det stora lejonet, som slukar ett djur eller en människa. Är det ondskan, som varnar den inträdande, eller är det Kristus i lejonets gestalt, som besegrar satan? Frågan får stå obesvarad, liksom i de fall där ett lejon från en portalomfattning bär ett människohuvud mellan sina öppnade käftar. Är det djävulen, som slukar en människa med hull och hår, eller är det dödsriket, som till uppståndelse och dom återbördar en själ?

LUNDS DOMKYRKA

Den medeltida ärkebiskopskyrkan i Lund var icke blott vid sin tillkomst utan är alltjämt den främsta romanska kyrkobyggnaden i Norden och därtill med internationell betydelse. Det omkring 1104 inrättade nya ärkestiftet utgjorde förutsättningen för dess tillkomst. Den vidgade liturgiska funktionen ställde ökade krav på en större kyrka, men byggnaden skulle också som ett synligt tecken hävda och manifestera den nya ställning, som biskopssätet skulle komma att intaga. Uppförandet av den nya ärkebiskopskyrkan synes genast ha satts igång. Vi känner ganska väl hur arbetet framskred genom den lyckliga omständigheten, att det till vår tid bevarats ett samtida kalendarium, ingående i handskriften Necrologium Lundense, i vilket införts anteckningar om de äldsta altarinvigningarna. År 1123 invigdes sålunda högaltaret i kryptan till Johannes döparens, alla patriarkers och profeters ära. Det magnifika kryptrummet under högkyrkans sanktuarium, kor och transept var inte därmed i sin helhet färdigt. Det blev det först i och med invigningen av altaret i det södra sidokapellet. Detta skedde 1131, och i omnämnandet härav säges dessutom, att relikerna från den gamla kyrkan överfördes till det nya kryptaltaret. Detta innebar, att Knut den Heliges kyrka fått stå kvar på den plats där den nya ärkebiskopskyr- kans långhus skulle resas, tills dess att kryptan kunde tagas i bruk som en fullständig kyrkolokal.

Genom en dödsnotis i Necrologiet känner vi också namnet på den byggmästare, som ledde arbetet på kyrkans planläggning och tidigaste uppförande. Han hette Donatus och benämnes på en gång både arkitekt och byggnadsledare, två titlar som sammantagna skvallrar om, att mannen varit i besittning av en icke ringa kompetens. Den del av kyrkan, som planlagts och rests under hans ledning, kännetecknas av en enkel men kraftfull och harmonisk arkitektur. Någon skulptural utsmyckning kom endast undantagsvis till stånd under detta skede, från vilket ännu främst kryptan men också den västligaste delen av långhuset kvarstår. De nedre delarna av tornpartiet, som sannolikt uppförts vid samma tid, revs olyckligtvis helt ner till grunden under 1800-talet då de nuvarande tornen tillkom. Självfallet fanns ingen inhemsk tradition för uppförande att ett byggnadsverk av denna storleksordning, utan impulserna hämtades utifrån. De synes ha kommit från områdena kring Engelska kanalen, de trakter med vilka Danmark traditionellt stått i förbindelse genom sina normandiska fränder.

Sedan den en gång så ståtliga katedralen i den moderna miljön mist något av den tidigare mera klart framträdande resningen, är det bortsett från kryptan inte i första hand arkitekturen från detta första byggnadsskede som i dag förlänar domkyrkan dess särprägel och mycket av dess berömmelse. Det har i stor utsträckning i stället blivit den rika skulpturvärld, som visserligen något decimerad men dock rikligt företrädd möter ens blickar på de flesta ställen inne i kyrkan och kring de medeltida ingångarna. Dessa skulpturer gör Lunds domkyrka till ett enastående monument i norra Europa, ett monument över de romanska stenmästarnas hantverksskicklighet, över en fantasi att symboliskt gestalta övernaturliga närvaroformer och över en internationalism, som i kyrkans hägn icke hämmades av några geografiska avstånd.

Under 1130-talet kan det nya skede i kyrkans byggnadshistoria tänkas ha inletts, under vilket arkitekturen kom att prydas med denna skulptur av närmast italienskt ursprung. Det var under samma årtionde som Donatus dog men också ärkebiskop Ascer.

Trots de bittra maktpolitiska stridigheterna fortsattes dock under efterträdaren Eskil arbetet på domkyrkan. Den äldre planen förändrades inte men vissa modifieringar gjordes i kyrkans resning. Den väsentligaste förändringen blev dock den nu på alla viktiga platser i byggnaden framträdande skulpturen. Den 1 september 1145 kunde så ärkebiskop Eskil inviga högkyrkan och dess altare till jungfru Marias och den helige Laurentii ära. I de båda sidokapellens altartitlar kom kyrkans skyddspatroner att som flankerande drabanter få de båda diakonhelgonen Vincentius och Stefanus, vilka i sin tur assisterades av var sitt krigarhelgon, Vincentius av den engelske Albanus och Stefanus av moren Mauritius, samtliga genom sina reliker närvarande i det södra respektive norra altaret. Denna genomtänkta representation var ett reellt uttryck för kyrkans centrala roll som Nordens viktigaste prästkyrka, karakteriserad genom diakonämbetet och skyddad av de heliga stridsmännen, och samtliga slutande sig till den heliga Jungfrun.

Som byggnad var domkyrkan ej färdig i och med invigningen av högaltaret 1145, ett av de ovannämnda sidoaltarna, det i norr invigdes för övrigt först följande år. Färdigställandet av långhusets östligaste del, den plats på vilken den äldre kyrkan från 1000- talet stått kvar ännu 1131, torde ej ha ägt rum förrän under slutet av 1100-talet. Men under årtiondena närmast före och efter århundradets mitt har säkerligen huvudparten av den skulpturala utsmyckningen tillkommit och absidexteriören fullbordats. Även om en hel del skulpturer måste anses ha gått förlorade under tidernas lopp, finns dock det mesta kvar från denna tid. De flesta befinner sig på sina ursprungligen avsedda platser såsom bilderna kring de bevarade portalerna och kapitälen i långhuset, men mycket har också fått byta plats. Hit hör t. ex. de förnämliga lejon- och serafskulpturena i det norra transeptet samt de i domkyrko- museet befintliga relieferna. Var dessa ursprungligen befunnit sig kan vara svårt att avgöra, men det är möjligt att de avsetts för det inre av kyrkan och markerat ingången till det allra heligaste, till sanktuariet. Det är också möjligt, att det redan var ärkebiskopen Absalon som lät flytta över dem till deras nuvarande platser i samband med en reformering av domkyrkan, som han vidtog 1187. Detta skulle innebära, att bilderna hängt samman med en liturgi, som man då frångick men samtidigt så uppsakttade deras uttrycks- värde, att de fick göra en ny tjänst i kyrkan. Det är kanske ingen tillfällighet, att de då fick sin plats i det kyrkorum, som synbarligen tjänat som ärkebiskopens speciella kapell.

Förståelsen för kyrkans romanska skulptur har i stora stycken varit levande under större delen av medeltiden, sannolikt inte så mycket beroende på en estetisk värdering av densamma som en viss form av förmåga till identifiering av de begrepp, som den gestaltar. I och med att igenkännandet uteblir slappnar emellertid också intresset och omvårdnaden av bilderna. Redan under senmedeltiden torde sålunda ornament och skulpturer, som suttit i vägen för nödvändiga byggnadsförändringar, saklöst ha undanskaffats. Någon aktiv förstörelse kan det emellertid knappast ha varit fråga om. Man skulle kunna tänka sig att, i analogi med vad som inträffade på vissa håll på kontinenten, en sådan ödeläg- gelse skulle ha skett i och med reformationen. Domkyrkan förskonades lyckligtvis härifrån, men gick dock en flerhundraårig förfallsperiod till mötes. Vanvården kan dock icke betecknas som en förstörelse, utan får närmast betraktas som ett resultat av byggnadens ändrade funktion. Från att ha varit Nordens mest framträdande biskops- och kanikkyrka i förbindelse med den europeiska kyrkogemenskapen förändrades den till framför allt en församlingskyrka i en nationalstat utan alltför livliga kontakter med europeiskt kyrkoliv. Under sådana omständigheter upphörde vissa delar av kyrkorummet att fungera, delar, som från början varit av framträdande liturgisk betydelse, bildmässigt konkretiserad genom skulpturen. Denna fick då i bästa fall ett kuriositetsvärde, som avskräckande minnen från en övertroisk tid.

Sedan Skåne och Lund 1658 blivit svenskt kom staden och kyrkan att bli än mer isolerade från omvärlder och mot slutet av 1700-talet kom oförståndet att taga sig aktivt uttryck. Man började behugga vissa av figurerna och hade ett allvarligt förslag om hela absidens nedrivande. Lyckligtvis stoppades huggerierna och rivningen förhindrades i sista stund. Under 1800-talet genomgick kyrkan två stora och mycket genomgripande restaureringar. De skedde delvis i en anda av ett nyvaknat romantiskt sinne för me- deltidskonsten. Detta innebar icke i och för sig en förståelse av dess specifika karaktär, men bidrog dock till en uppskattning, som lade grunden till ett fortsatt studium. När kyrkan i dag åter står nyrestaurerad, tror vi oss samtidigt hysa en större och verkligare uppskattning av skulpturens konstnärliga värden samt ana något litet av dess dolda betydelse.

I sin nordiska miljö fascinerar domkyrkoskulpturen betraktaren. Till stora delar är den en främmande fågel här, men man upptäcker snart hur den på grund av en förvandling under tillkomstårtiondena kring 1100-talets mitt rymmer mycket av allmängiltighet men också antydningar om lokal ursprunglighet. Ser man skulpturerna sammantagna, så som man kan betrakta dem i bilderna, upptäcker man än mer de rika skiftningarna, och att någonting händer. Det är inte i första hand fråga om ett stilistiskt skeende utan om en rörelse utanför tid och rum, en gestaltning av de inre spänningar, som alstrat bilden och betingat dess samhörighet med byggnade.

I verkligheten är det svårt att ens bli varse den lilla relief med Adam och Eva, som i ett bågfält sitter över norra sidoskeppspor- talen. Men på den här återgivna bilden ser vi vad som händer. De summariska »klippdockorna« berättar själva om det ögonblick, då de pålade sig och oss de mänskliga villkoren. Eva äter av frukten och räcker utan entusiasm en bit åt Adam, som med en klapp på magen synes att redan ha känt den bitterljuva sötman; eller har han blivit varse sin nakenhet, som han med handen försöker dölja. Det är betecknande, att det är den undskyllande och kvinnan anklagande Adam, som vänder sig mot åskådaren, medan Eva vänder sig bort från honom. Allting händer på en gång och i samma rörelser hos två gestalter, som ej är statiska utan befinner sig i både vila och rörelse. Adams huvud och överkropp är fixerade i sin frontalitet, men med benen springer han. Figurerna rör sig inte i ett rum eller mot ett mål, de svävar, ja nästan simmar i den bakgrund till vilken de är bundna, och som utgör deras existenssfär i evigheten. Skildringen är allmängiltig genom att vara naivt levande och fri från stilistiskt eller tektoniskt normerade betingelser.

Denna obundenhet och frihet gentemot de i yttre bemärkelse ordnande principerna är ett undantag bland figurskulpturerna i domkyrkan. Ur ett arkitektoniskt sammanhang växer den plastiska människobilden fram. Som atlanter tjänstgör de kraftfulla gestalterna i södra sidoskeppet som bärare av den tyngd, som en av valvens gördelbågar pålägger dem. De ersätter det korintiska kapitälets voluter men har övervunnit den abstrakta tek- toniska formen genom sin gestaltmässighet och den grad av aktivitet, som de ger uttryck åt genom att stödja sig mot en nedre krans av akantusblad, den enda kvarvarande resten av det antika växtkapitälet.

Denna skulptur sitter ännu på sin ursprungliga plats och tager ännu del i den helhetsfunktion, som den från början avsetts för. Så är tyvärr ej fallet med bilden av den tronande Kristus och en ärkeängel, vilka förvaras i domkyrkomuseet. Vilken plats de och ännu en men nu försvunnen ärkeängel ursprungligen innehaft i kyrkan är icke helt visst. Okunnigheten härom försvårar också den omedelbara tydningen av gestalterna, icke tydningen av vad de föreställer men av deras betydelsemässiga funktion. Helhetsverkan har gått förlorad. Men ännu stiger Kristusgestalten fram som plastisk verkliggörelse ur bakgrundens evighetssfär. I den inkarnerade Gudens gestalt har människobilden lösgjort sig ur den ytmässiga skuggvärld i vilken Adam och Eva levde, befriat sig från det tektoniska tvång, som betingade de båda atlanternas exis- stens i sidoskeppskapitälet, och tagit kroppslig gestalt för att i samma mån frammana de heliga gestalter, som omgett den. De existerande färgfragmenten ger en antydan om den lyskraft, som en gång utgått från gestalten. Då har också ögonen varit levande och förlänat den i formen vilande gestalten full aktivitet, icke den fysiska rörelsens aktivitet utan den andliga verkningskraftens, gränslös i den evighetens dimension ur vilken bilden även som formskapelse stiger.