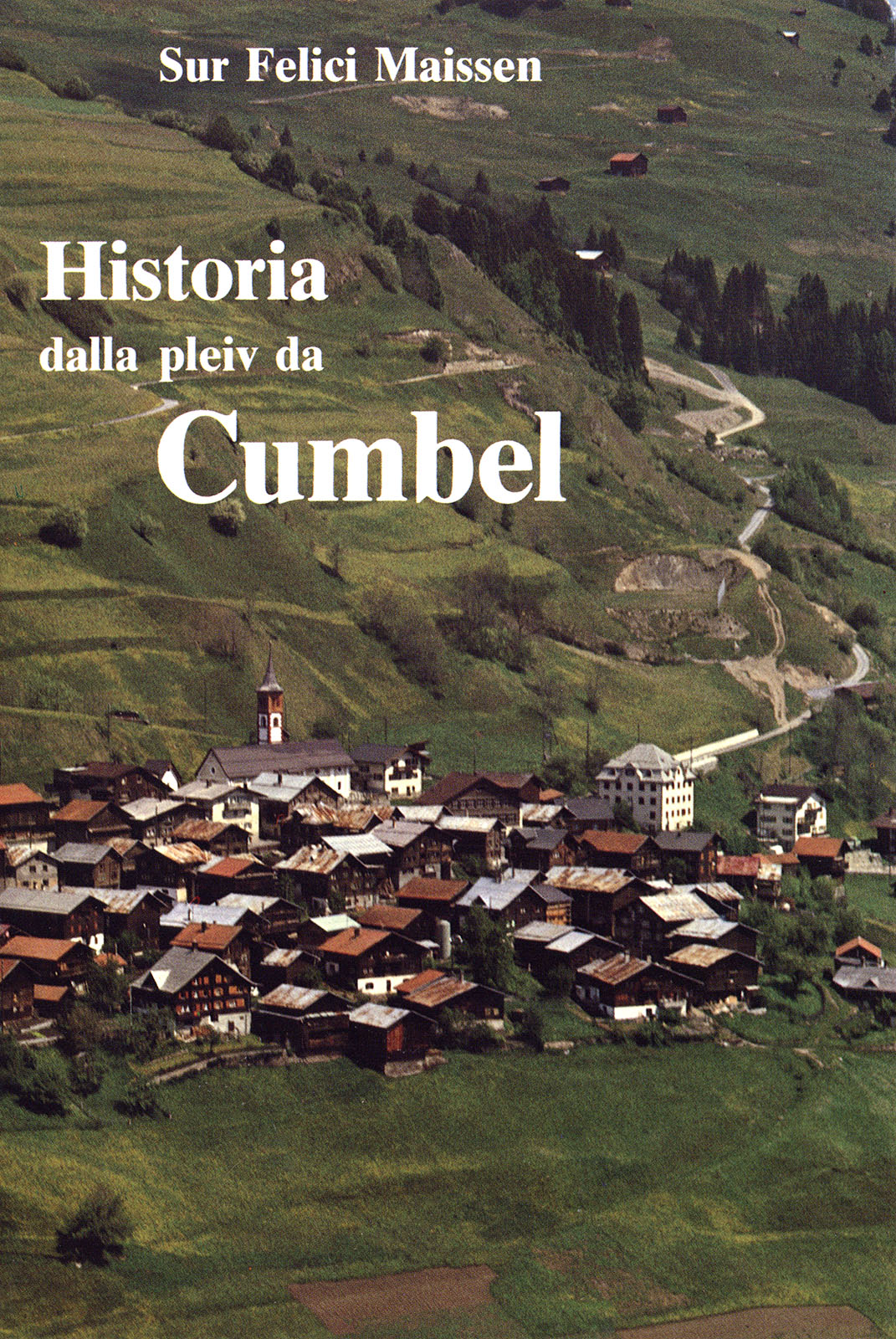

History of the Parish of Cumbel (Historia dalla pleiv da Cumbel) a parish history written in Sursilvan Romansh by the historian and priest Felici Maissen, published in 1983 by Casa editura Desertina at Mustér (Disentis), Switzerland. Spanning sixteen chapters and 264 pages, it chronicles the Catholic parish of Cumbel in the Val Lumnezia from the early medieval period through the 1980s, drawing on parish archives, baptismal and death registers, communal protocols, cantonal records, and oral tradition to document the ecclesiastical, political, demographic, and cultural life of a small Alpine community across six centuries.

The book was published during a period of accelerating change in the Romansh-speaking valleys of Graubünden, as depopulation, municipal consolidation, and the retreat of traditional agrarian life threatened to sever communities from the archival and oral sources that documented their past. Maissen, himself a priest and a prolific historian of the Three Leagues (Drei Bünde), produced the work as both a scholarly record and an act of cultural preservation, writing in the Sursilvan dialect spoken by the people whose history he narrated. The parish of Cumbel - first attested as Cumble around 825 - would merge with seven neighboring communes into the municipality of Lumnezia on 1 January 2013, making Maissen’s book the final comprehensive history of Cumbel as an independent civil and ecclesiastical entity.1

The Author

Felici Maissen (referred to throughout his career with the clerical honorific Sur) was a Catholic priest and one of the most productive historians of Graubünden in the second half of the twentieth century. His principal scholarly work, Die Drei Bünde in der zweiten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts (The Three Leagues in the Second Half of the 17th Century), was published by Sauerländer at Aarau in 1966 and ran to 430 pages covering the political, ecclesiastical, and cultural history of the Rhaetian free state from the Religious Pacification of 1647 to 1657.2 He published extensively in the Bündner Monatsblatt and the Jahresbericht der Historisch-antiquarischen Gesellschaft von Graubünden, contributing studies on subjects ranging from the Venetian-Grisons alliance of 1706 to Grisons students at the universities of Dillingen, Strasbourg, Heidelberg, Innsbruck, Milan, Vienna, and Freiburg im Breisgau.3 In collaboration with his brother Aluis, he also produced a biography of the seventeenth-century Grisons governor Nicolaus Maissen, published by Desertina in 1985.4

The History of the Parish of Cumbel represents a departure from these German-language academic publications. Written entirely in Sursilvan Romansh, it addresses the community in its own language, grounding its narrative in the parish and communal archives at Cumbel (ApC and AcC) and the episcopal archive at Chur (AEC), supplemented by cantonal records at the Staatsarchiv Graubünden. The apparatus of 661 footnotes, running across a separate endnote section, cites original documents in Romansh, Italian, Latin, and German, often reproducing passages at length.

Cumbel and the Val Lumnezia

Cumbel sits at the entrance to the Val Lumnezia (German: Lugnez), a south-running side valley of the Vorderrhein in the Surselva region of Graubünden. The village is built at the foot of the Porclas, a medieval defensive gate also known as the Frauentor (Women’s Gate), commemorating the legendary battle of 1352 in which the women of the Lumnezia drove back the troops of the Count of Werdenberg by rolling stones down on them from the heights.5 The coat of arms of Cumbel depicts this gate. With an area of 4.5 square kilometers and a population that fluctuated between roughly 240 and 340 over the period covered by the book, Cumbel was never large, but its location at the valley’s mouth - where the road from Glion (Ilanz) enters the Lumnezia - gave it a certain administrative weight, and its citizens produced a disproportionate number of district officials, physicians, and political figures.

The valley remained almost entirely Romansh-speaking and Catholic. As late as the 2000 Swiss census, 85.1% of Cumbel’s population reported Sursilvan as their primary language.6 This linguistic continuity shaped the parish archives: the registers of baptisms and deaths (maintained from 1651 onward) are kept in Latin, Italian, Romansh, and German, reflecting the successive languages of ecclesiastical administration, while the communal protocols - beginning in 1772, when the young physician Dr. Gieri Antoni Vieli inaugurated them with a German heading - gradually shifted to Romansh over the course of the nineteenth century.

Structure and Contents

Maissen organized the book into sixteen chapters (parts), moving roughly from the ecclesiastical to the civil, from the institutional to the biographical, and from the deep past to the living present.

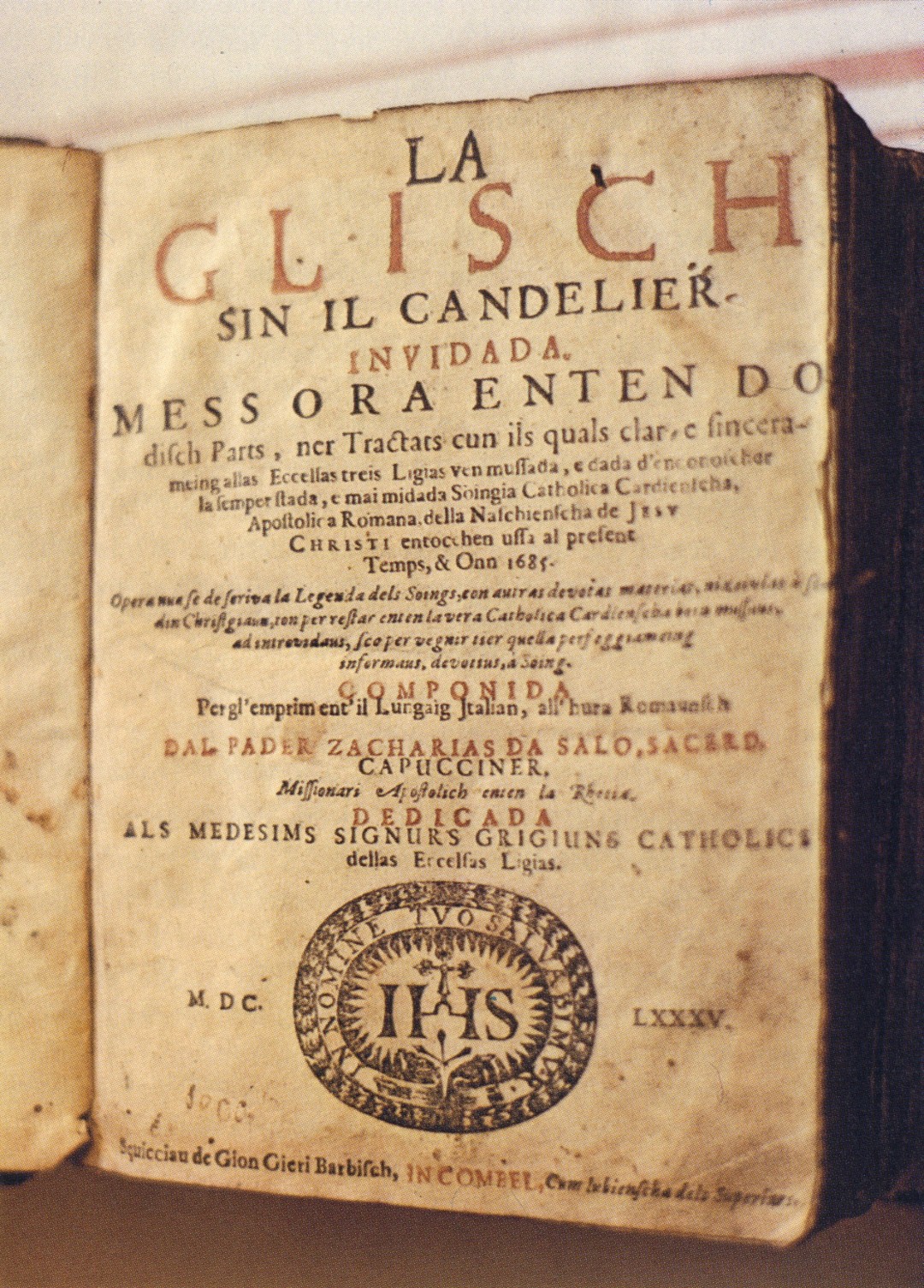

The opening chapters establish the medieval foundations: the Chapel of St. Mauritius near Valgronda, attested around 825; the dependency of Cumbel on the mother church of St. Vincent at Pleif (Vella); and the arrival of the Capuchin mission in 1649, which would serve the parish continuously until 1923. The Capuchins had been sent to the Rhaetian valleys as agents of the Counter-Reformation, and Maissen documents their campaign against Protestant infiltration with particular attention to the literary activity of P. Zaccarias da Salò, who spent the last twenty-one years of his life at Cumbel (1684–1705) and whose La Glisch sil candelier envidada (The Light on the Candlestick Lit, 1685–87) was among the earliest substantial works printed in Sursilvan Romansh. The itinerant printer Gion Gieri Barbisch of Bludenz in the Vorarlberg set up his press in Cumbel’s rectory expressly for the purpose, bringing with him the apprentice Pieder Maron of Panaduz, who would later establish his own printing house.7

The central portion of the book treats the parish church of S. Stiafen (St. Stephen), describing its construction at the beginning of the sixteenth century, its Baroque embellishments of 1680 and 1709, and the restorations of 1978–79. Maissen inventories the church’s relics (authenticated certificates from the late seventeenth century onward), its side altars, its bells, and the eight chapels scattered across the parish territory. He provides a complete register of the fifty-seven clerics who served the parish between 1649 and 1968, tracing them through the Capuchin provincial catalogues compiled by the Swiss Capuchin historian Willi.

Religious life is documented in extraordinary detail. At its height, the parish calendar included over fifty-one holy days, and at least fourteen confraternities were active at various periods. Seven Capuchin missions were conducted between 1845 and 1980. Maissen catalogs the customs surrounding each: the New Year’s ceremony in which young men, young women, and children came in turn to the rectory to wish the father a good year (receiving a small card, a glass of spirits, and two or three centimes, respectively); the Good Friday procession with a life-size figure of Christ borne in a bier; the distribution of communion wine, a practice whose abolition the parishioners contested with the bishop in 1744; and the obligation for women to appear in church with heads covered in the Italian manner, which P. Nicolaus in 1872 defended with the warning that any relaxation would encourage women in their “ambitious and sinful intent.”8

The Frescoes of Hans Ardüser

The most artistically distinctive feature of the nave of S. Stiafen is a pair of wall paintings that Maissen tentatively attributes to Hans Ardüser (1557–1617), one of the most characteristic visual artists to emerge from Graubünden in the late sixteenth century. On the upper side of the nave, a cycle depicting the Ten Joys of Our Lady runs along the wall; on the lower side, a fresco of the Battle of Mundaun commemorates one of the violent episodes of the Bündner Wirren (1618–1639), the decades-long conflict in which Habsburg and French intervention tore apart the Three Leagues and brought foreign troops repeatedly through the Surselva. Maissen dates both works to approximately a century after the Gothic construction of the nave, placing them around the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, and notes that Ardüser “is known to have also worked in the Lumnezia, for example on the chapel of St. Roc at Vella.”9 The attribution remains probable rather than documented: unlike several of Ardüser’s confirmed works, the Cumbel paintings bear no signature, and the episcopal visitation protocols for the Lumnezia of 1623 and 1643 - which would be the most likely sources of contemporary documentation - make no mention of the church at Cumbel at all.

Hans Ardüser was born in Davos in 1557, the son of a master builder who constructed the great chamber of the Davos town hall. After studies at the Latin school in Chur and a brief apprenticeship in Feldkirch, he trained as a facade painter under Franz Appenzäller in Chur before establishing himself as an itinerant artist and winter schoolmaster, traveling on foot through the canton each summer to offer his services.10 In 1583 he married Menga Malet of Lantsch/Lenz, who accompanied him on his journeys until her death in 1603. During a career spanning roughly four decades, Ardüser decorated the facades and interiors of private houses and churches of both confessions across more than forty-five villages; despite being Reformed, he was engaged repeatedly by Catholic patrons.11 Of the more than one hundred works he recorded in his own chronicles, covering over 150 houses and churches, fewer than twenty have survived. His confirmed work at the chapel of St. Roc and St. Gian (Sogn Roc e Sogn Bistgaun) at Vella - the Lumnezia example Maissen cites - includes a restored fresco of the Ray Wreath Madonna with two saints on the exterior wall and further paintings in the interior, featuring a small winged altar with members of the local de Mont family.12

Ardüser’s style is immediately recognizable: exuberant in ornament, freely drawn from printed sources including chronicles, zoological books, and religious texts, and largely unconcerned with strict anatomical proportion or spatial perspective. The “unconcerned manner in which Ardüser translates lush ornaments, contemporary costumes, classical allegories, biblical scenes, and exotic animals into the monumental” - in the formulation of one modern assessment - gives his surviving work a directness that distinguishes it from the trained fresco tradition.13 His colorful and narrative approach would have suited both subjects at Cumbel: the Joys of Mary as a devotional sequence and the Battle of Mundaun as a topical commemoration of a military event within living memory of the parish.

The Cumbel frescoes were not uncovered until the partial restoration of 1955 under sur Lezi Antoni Baselgia, when workers revealed the paintings of the Ten Joys of Mary, the images of the apostles, and the Battle of Mundaun beneath successive layers of overpainting. Much had already been lost: during the 1905/07 restoration under P. Urban, “a good deal of the earlier paintings was destroyed” when the vault received new devotional compositions and the church was extensively refashioned in the taste of the period. The Battle of Mundaun fresco is a rare surviving instance of a local commemoration of the Bündner Wirren - remarkable evidence that the community at the exposed entrance to the Lumnezia, with its Protestant neighbors immediately to the north and Habsburg troops passing through the valley during the conflict, found reason to memorialize the military crisis in paint on the walls of its church alongside the traditional devotional imagery of the Virgin.

Demographic and Social History

Among the book’s most striking sections is the demographic survey. Maissen compiled data on population (1772–1980), births, deaths, marriage ages, consanguinity, and infant mortality, drawing on parish registers that recorded every baptism and burial. The figures reveal catastrophic childhood mortality across the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries: roughly one-third of all children born in the parish died before adulthood. Life expectancy for those who survived past fifteen rose from approximately 51½ years in the earlier periods to 77⅙ years by the mid-twentieth century.

The 1884 census provides a snapshot of the social structure. Of 435 citizens, 251 bore the surname Arpagaus and the rest were distributed among Caduff, Elvedi, Collenberg, Cavegn, Casanova, and Vieli - the seven “existing” family names. Maissen traces over one hundred additional surnames that had appeared in the parish records between 1397 and 1866 and subsequently vanished, most through emigration or extinction. He tells the story of the Elvedi family’s origin: a Hungarian deserter named Andriu Elvedi arrived in Cumbel around 1795, married, and founded a lineage that persisted into the author’s own time.

The analysis of forenames is equally detailed. Among 399 male names recorded, Gion and Antoni together accounted for 141 - a third of the total. The byname system (surannums), by which individuals were distinguished within this narrow pool of given names, is catalogued with the specificity of a linguistic fieldwork report.

Economy and Emigration

Maissen devotes sustained attention to the parish’s economic foundations: the benefice (pervenda), its income from tithes, bequests, and agricultural land; the school fund established in 1851; the complex system of poor relief (spenda) under which indigent parishioners were fed in rotation by their neighbors; and the 1887 economic census, which revealed wealth stratification ranging from 1,000 to 23,000 francs.

The emigration chronicle is particularly affecting. Drawing on death notices, letters, and oral reports, Maissen reconstructed the fates of over one hundred Cumbel natives who died abroad between 1659 and 1959 - in France, Italy, Austria, Spain, the Netherlands, England, Hungary, and the Americas. The list includes soldiers in foreign service (mercenaries from the 1650s through the Napoleonic period), seasonal laborers, pastry chefs, innkeepers, and domestic servants. A fourteen-year-old boy drowned in a river in France in 1743. A woman died in childbed at Bordeaux in 1828. Three men were killed in the revolutionary fighting at Paris in 1848. The entries are terse, drawn from formulaic death register notices, but their cumulative weight conveys the scale of displacement from a community of fewer than three hundred souls.

Communal Life and Modernity

The later chapters treat the secular affairs of the commune with the same archival thoroughness. The decade-long dispute over the route of the Lumnezia road (1860s–1873) is reconstructed from correspondence preserved in the cantonal archive, including a memorable protest letter from Councillor Th. Arpagaus to the Small Council in which he complained that the state engineers had never deigned to greet the communal authorities, and concluded: “Even if we are peasants and not people of higher studies, we know nevertheless that a servant of the state is there for the people and not the people for him.”14

The resistance to the automobile forms a comic and revealing sequence. In 1916, the commune unanimously resolved not to lift the automobile ban. In January 1925, the cantonal vote on automobile traffic was rejected at Cumbel 53 to 15. On 26 June 1925, in what proved to be the decisive cantonal vote permitting automobile traffic, Cumbel voted 47 no, 8 yes. It was not until July 1926 that the commune voted 25–2 to open the road to automobiles for the current year, having been offered a corresponding subsidy. The maximum speed was fixed at 12 kilometers per hour through the village.15

The night watchman (guardia da notg) - a figure who made his rounds through the village toward midnight, singing a song or sounding a horn - is documented from 1862 communal law through his final abolition on 27 April 1952, when the commune unanimously resolved to discontinue the position “but not the inn patrol.” Women occasionally served in the role: Giuanna Collenberg in 1891.16

The Chronicle of Misfortunes

The final chapter, titled Cronica da disgrazias, records thirty-four fatal accidents between 1664 and 1980, drawn from the parish death register. The litany of drownings, falls from cliffs, deaths under falling trees, and timber-hauling accidents reads as a catalogue of the dangers inherent in alpine pastoral life. Two sisters, Urschla and Barla Caglier, were found frozen at the Splügen pass in 1675. In 1888, mistral Gion Arpagaus, aged 28, drowned in the ravine of Duin while trying to rescue his fellow citizen from a flood - an entry Maissen annotated simply as “a sacrifice of charity.”17

The book closes with the eleven-stanza Canzun da s. Stiafen (Song of St. Stephen), a hymn to the parish patron attested in all seven editions of the Consolaziun dell’olma devoziusa (1690–1856), and three melodic variants from the Lumnezia valley. The Cumbel melody itself was never recorded - a final, irreversible loss that the author notes with regret.

Significance

The History of the Parish of Cumbel belongs to a tradition of Swiss parish and communal histories that extends back to the eighteenth century, but it is distinguished by its language, its archival density, and the completeness of its coverage. Few comparable works exist in Sursilvan Romansh. Published by Casa editura Desertina at Mustér - the Benedictine monastery town that has served as a center of Romansh culture since the early Middle Ages - the book preserves a record of communal life at the moment of its transformation, when the old structures of parish assembly, night watchman, field warden, and impounding officer were passing from living memory into the archive.18

Explore the Book

This is a preview only - view fullsize on archive.org

Gallery

Notes

-

Cumbel merged with Degen, Lumbrein, Morissen, Suraua, Vignogn, Vella, and Vrin on 1 January 2013 to form the municipality of Lumnezia. See “Cumbel,” Wikipedia, accessed 15 February 2026. ↩

-

Felici Maissen, Die Drei Bünde in der zweiten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts in politischer, kirchlicher, kirchengeschichtlicher und volkskundlicher Schau. Erster Teil: Die Zeit der Unruhen von der Religionspazifikation 1647 bis 1657 (Aarau: Sauerländer, 1966), 430 pp. Listed in ZVAB under “Maissen, Sur Felici.” ↩

-

Among his published studies: “Bündner Studenten in Dillingen von 1551–1800,” JHGG 90 (1960), pp. 83–142; “Bündner Studenten an der alten Universität Strassburg 1621–1794,” JHGG 120 (1990), pp. 127–152; “Die Bündnerisch-Venezianische Allianz von 1706,” Bündner Monatsblatt 1964, pp. 81–144. ↩

-

Felici Maissen and Aluis Maissen, Nicolaus Maissen: Sia veta e siu temps 1621–1678 (Mustér: Ed. Desertina, 1985), xiv + 163 pp. ↩

-

“Porclas, Lumnezia,” Graubünden Tourism, accessed 15 February 2026. See also “Remembering Switzerland’s Forgotten Heroines,” SWI swissinfo.ch. ↩

-

“Cumbel,” Wikipedia, citing the 2000 Swiss federal census. ↩

-

Maissen, Historia dalla pleiv da Cumbel, ch. XIV, section on P. Zaccarias da Salò, with footnotes 638–641 citing the studies of Prof. G. Gadola and P. Iso Müller. ↩

-

Maissen, Historia, ch. XIII, section on customs (dretgiras e isanzas). The head-covering passage is from P. Nicolaus’s 1872 Agenda, preserved in the parish archive. ↩

-

Maissen, Historia, ch. IX, section on the parish church, fn. 136. The original passage: “ils maletgs cun las Legrezzas da Nossadunna dalla vart dadora e cun la Battaglia da Mundaun dalla vart da sut han pudieu vegni fatgs in tei ca tschient onns plitard ed eissigi pussibel tranter ils mauns dil conoschiu pictur e meister Hans Ardüser.” Maissen cites fn. 136 in context of Ardüser’s known work in the valley. ↩

-

Alfred Wyss, “Ardüser, Hans (der Jüngere),” in Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz; see also “Hans Ardüser,” Wikipedia (German), accessed 18 February 2026. ↩

-

“Rund 150 Häuser und Kirchen” across the canton are attributed to Ardüser, of which roughly twenty survive. See “Auf den Spuren eines Wandermalers,” Südostschweiz, 3 January 2020, citing research by Walter Müller; and “Hans Ardüser,” Surselva Tourismus, accessed 18 February 2026. ↩

-

“Chapel Sogn Roc e Sogn Bistgaun, Vella,” Graubünden Tourism, accessed 18 February 2026. The chapel was founded in 1592 by district judge Gallus of Mont during a plague epidemic; Ardüser’s paintings were later supplemented by a new facade by Alois Carigiet in 1940. ↩

-

Cited in “Hans Ardüser,” Wikipedia (German), quoting an assessment of his style: the passage describes how Ardüser “translates lush ornaments, contemporary costumes, ancient allegories, biblical scenes, and exotic animals into the monumental … in an unconcerned, additive manner that grants his work a freshness and directness without equal.” The German original reads: “Die unbekümmerte Art aber, in der Ardüser … üppige Ornamente, zeitgenössische Kostüme, antike Allegorien, biblische Szene, exotische Tiere ins Monumentale überträgt … verleiht seinem Werk eine Frische und Eindringlichkeit, die ihresgleichen sucht.” ↩

-

Maissen, Historia, ch. XII, section on the Lumnezia road, citing correspondence in the cantonal archive. The letter from Councillor Th. Arpagaus is reproduced in the original Romansh. ↩

-

Maissen, Historia, ch. XII, section “this and that” (quei e tschei), citing communal protocols from 1916, 1924, 1925, and 1926. ↩

-

Maissen, Historia, ch. XII, section on the night watchman (guardia da notg), citing communal law of 1862 and subsequent resolutions. ↩

-

Maissen, Historia, ch. XVI, Cronica da disgrazias, entry for 11 September 1888, drawn from the parish death register. Mistral Gion Arpagaus was the son of Dr. med. Gion Barclamiu Arpagaus, National Councillor. ↩

-

On Disentis/Mustér as a center of Romansh culture, see “Disentis/Mustér,” Wikipedia. On Casa editura Desertina, see the Princeton University Library catalog entry (OCLC 11068127). ↩