Lower Fort Garry: A History of the Stone Fort

LOWER FORT GARRY: A HISTORY OF THE STONE FORT

By

ROBERT WATSON

WINNIPEG

1928

Copyright 1928 by Hudson’s Bay Company

First Edition

FOREWORD

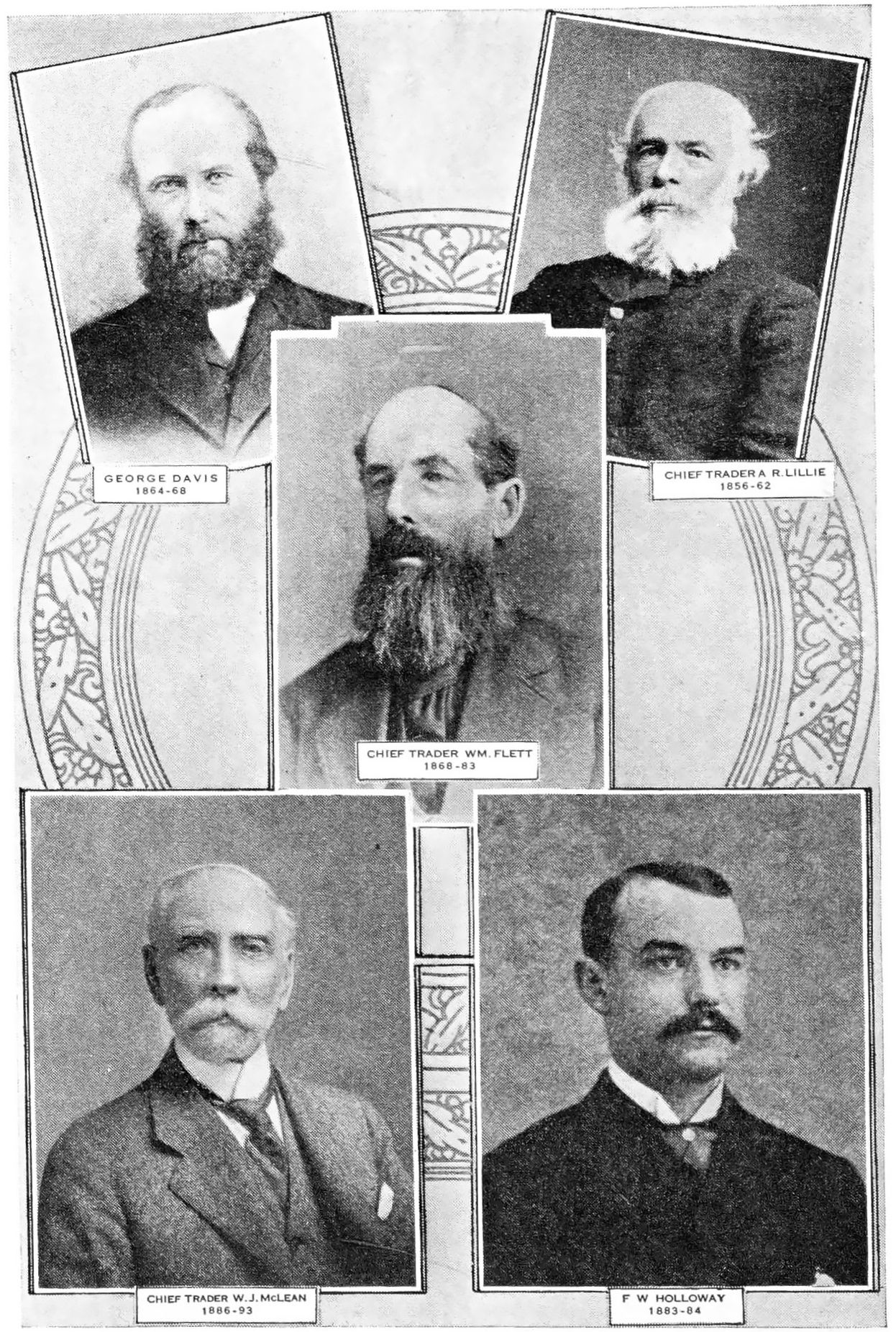

THE author wishes to thank the many friends who have assisted him in collecting the material he required. This material has taken the form of information and of photographs. Amongst those whom it is desired specially to mention are the following: Messrs. Alfred Franks, J. R. Bunn, W. J. Healy, W. F. Alloway, T. Clouston, W. S. Lecky, A. Caskey, Chief Trader W. J. McLean, Sheriff Colin Inkster, Mrs. A. R. Lillie, and the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Reference has also been made to the undermentioned works, for which acknowledgment is duly given.

-

The Red River Settlement, by Alexander Ross.

-

Notes of the Flood at Red River in 1852, by David Anderson, D.D.

-

Red River, by Joseph James Hargrave.

-

The Remarkable History of the Hudson’s Bay Company, by George Bryce, M.A., LL.D.

-

The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba, the North-West Territories and Kee-wa-tin, by Hon. Alex. Morris, P.C. Rough Times, 1870-1920, by Bugler F. Tennant.

-

History of Manitoba, by Hon. Donald Gunn.

-

Women of Red River, by W. J. Healy.

-

The Company of Adventurers, by Isaac Cowie.

-

Freemasonry in Manitoba, 1864-1925, by William Douglas.

-

The Father of St. Kilda, by Roderick Campbell. History of the North-West, by Alexander Begg.

-

Extracts from the Archives of the Hudson’s Bay Company, London, England.

The author looks forward to the time (which it is understood is not far distant) when certain records of the Hudson’s Bay Company are published. So soon as this event takes place, this brief history will probably have to be amplified in the light of the information which will then be available.

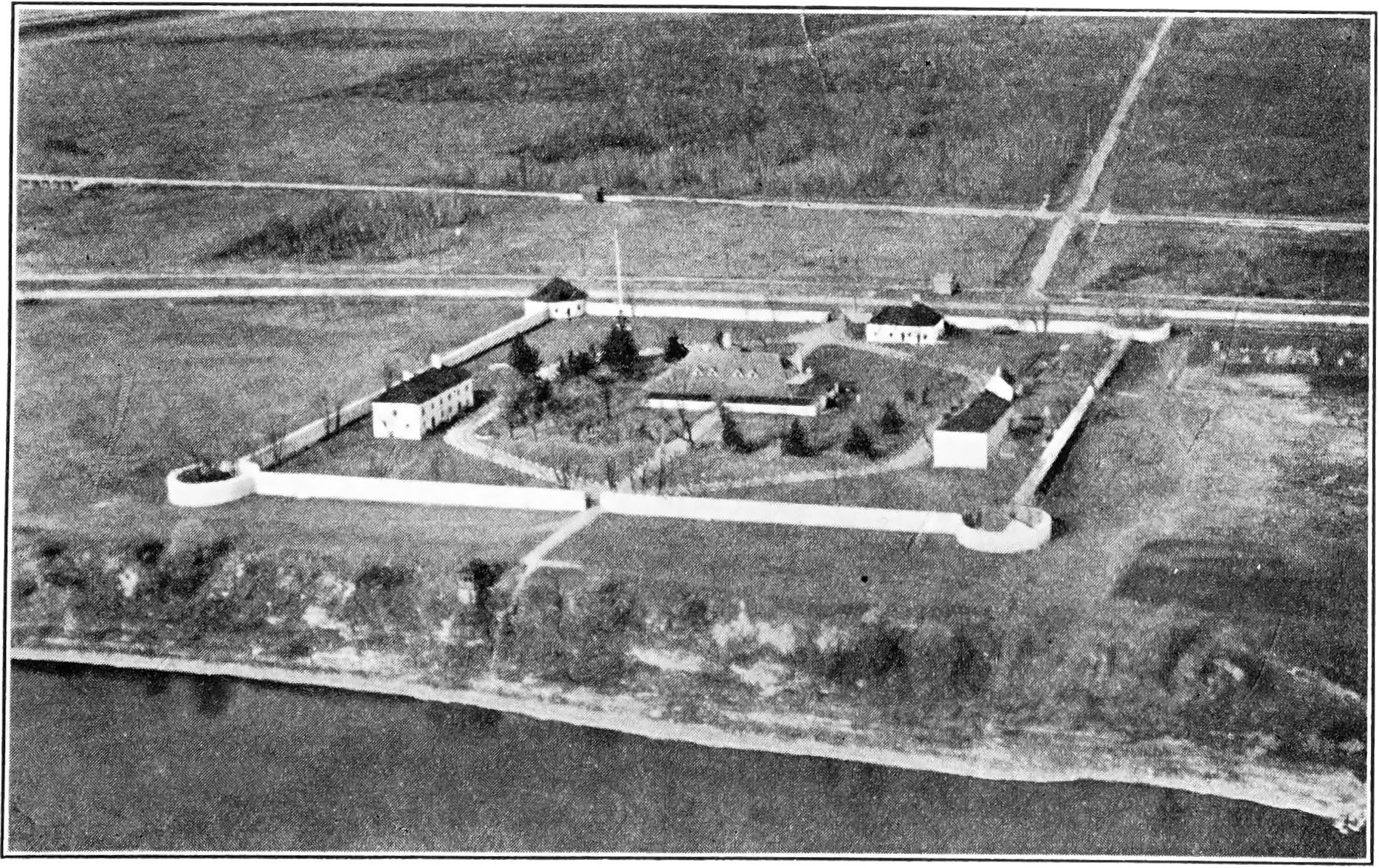

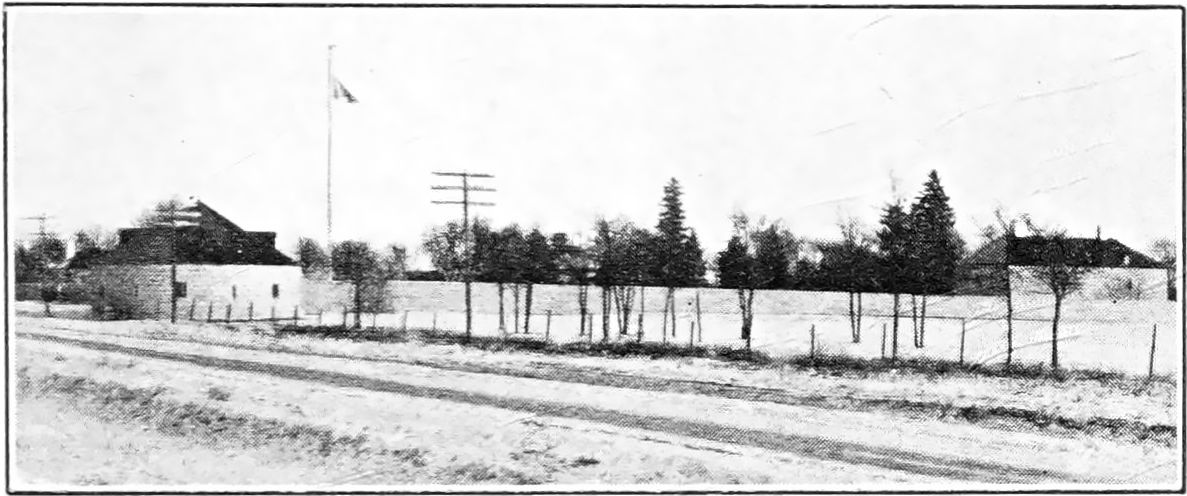

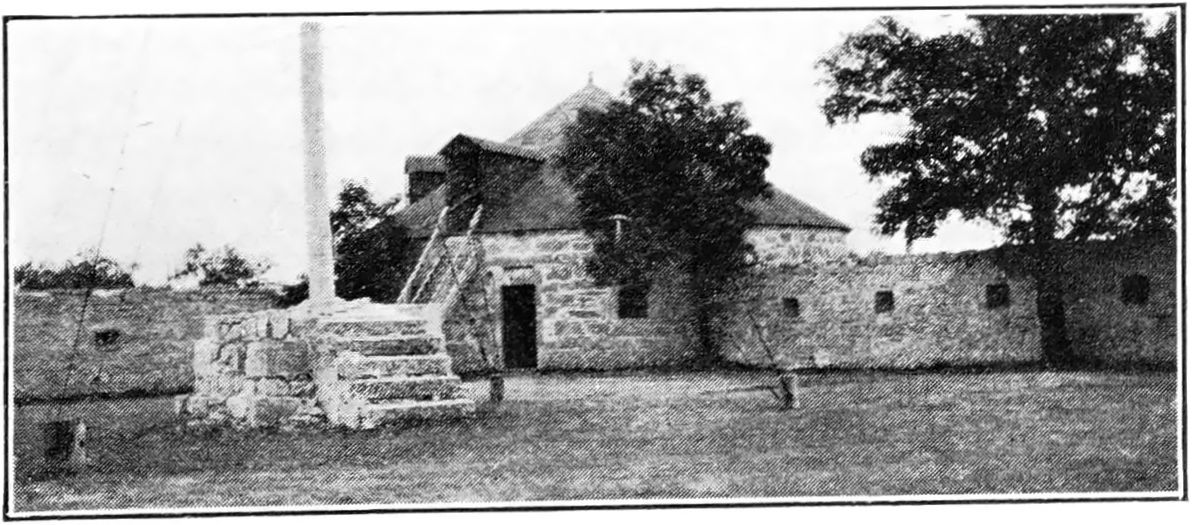

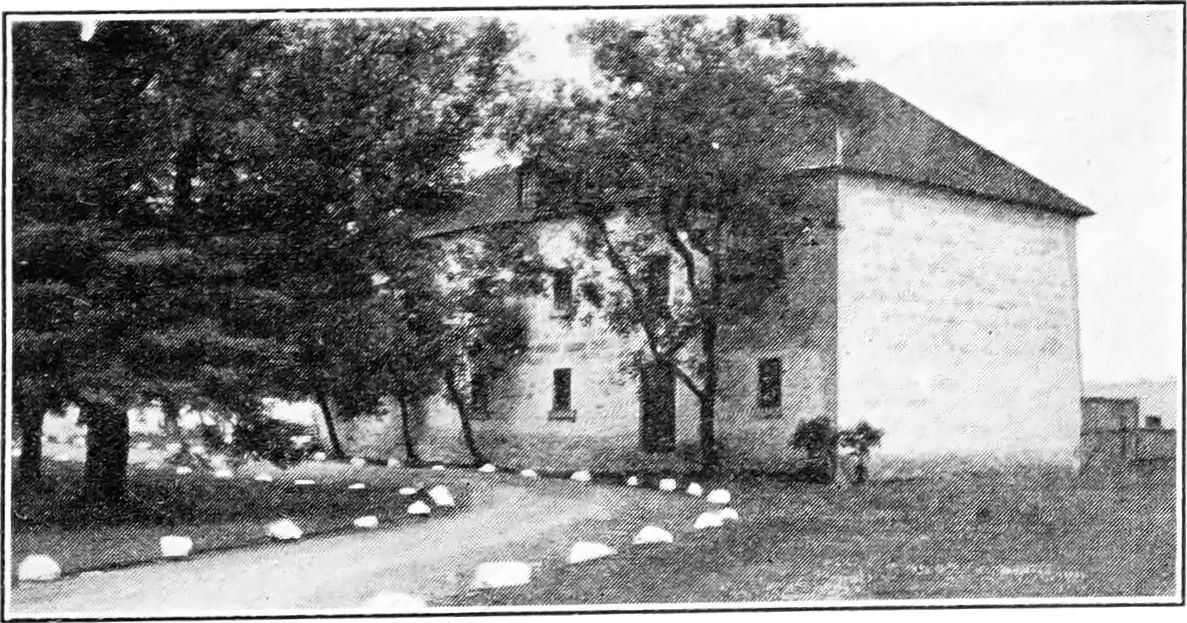

The Stone Fort Is Planned

TWENTY miles to the north of the city of Winnipeg, in the Province of Manitoba, there stands between the highway and the Red river, on the dividing line of the parishes of St. Andrew’s and St. Clement’s—neat, symmetrical and pleasing to the eye—an old, stone-walled fort, with loopholes and bastions, built by “The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay.”

To the Selkirk settlers and the men of the Red River settlement in the shadow of old Fort Garry, it was known as the Lower Fort, but to the far-flung west that extended from Oregon to the mouth of the Mackenzie, to the traders on the north shore of Lake Superior, in the conversation and light gossip of the officers and servants of the Hudson’s Bay Company, by the teepee fires and in the wigwam councils of the red men of the north, it was ever distinctively alluded to as “The Stone Fort.”

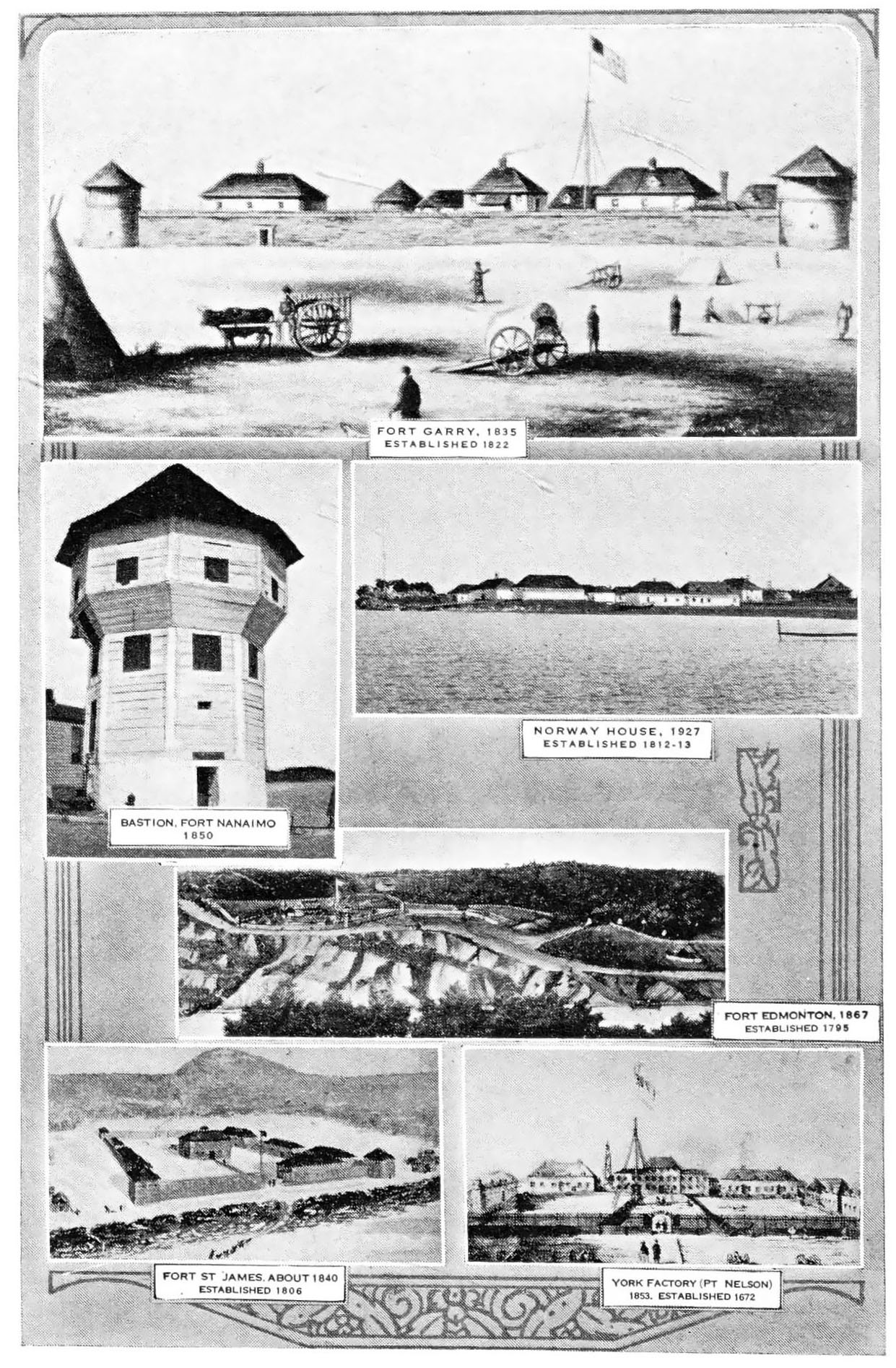

The erection of the first stone fort, Fort Prince of Wales, was commenced by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1733, at the mouth of the Churchill river on Hudson Bay, as a safeguard against the depredations of the French and of the Indians. The plans for Fort Prince of Wales were prepared by military engineers who served under the Duke of Marlborough. Its walls were twenty-five feet thick and it was considered impregnable but, in 1782, when manned by only thirty-nine men under Governor Samuel Hearne (the noted discoverer of Coppermine river) it surrendered to Admiral de la Perouse with three French men-of-war. The fort was looted by a force of four hundred men. Its stout walls resisted total demolition, and to-day stand an impressive ruin, marking the site of the strongest and the most northerly stone fortress on the continent of North America.

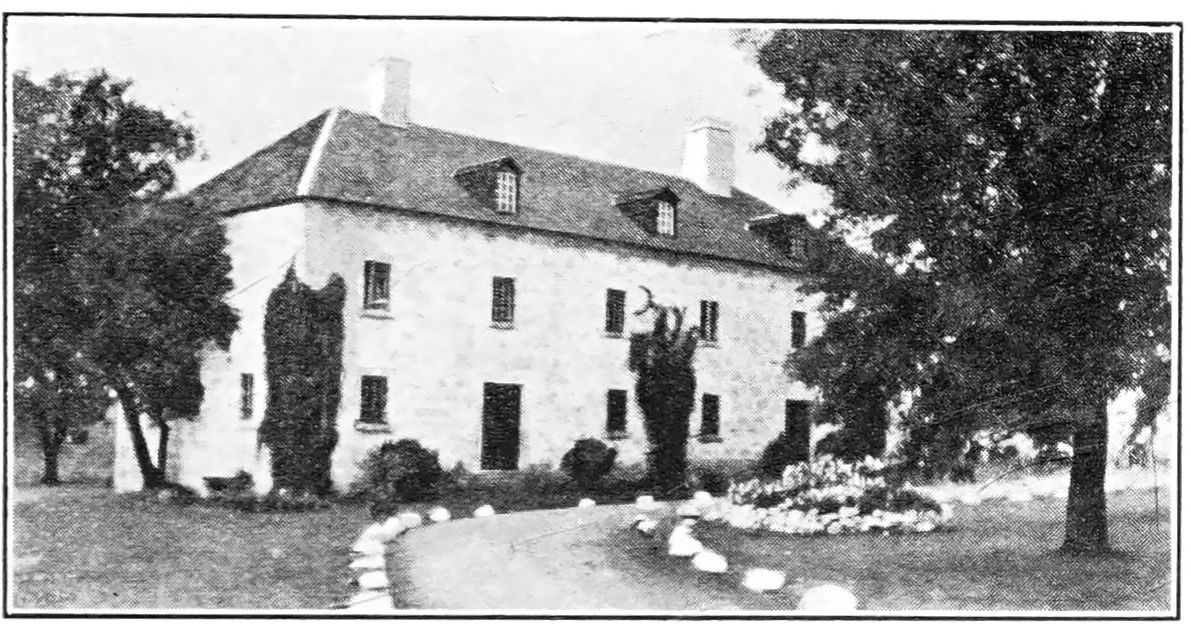

The building of Lower Fort Garry on the west bank of the Red river was commenced in 1831 and completed in 1839. It is understood to have been constructed from plans drawn by Chief Factor Alexander Christie, twice Governor of Assiniboia and the officer in charge of the Red River district. Governor Alexander Christie served the Company faithfully for thirty-eight years. He retired in 1849 to Edinburgh, Scotland. He was probably the most influential and deeply respected chief factor of his time. In addition to the seven years’ retiring allowance in the profits of the fur trade to which he was entitled, he was accorded by the Company, with the approbation of his brother officers and Sir George Simpson, the Governor-in-Chief, two years’ additional share in the profits. The Christie family, of whom Governor Alexander Christie was the head, has given over 240 years’ service to the Hudson’s Bay Company.

In 1830, at the Council meeting of Hudson’s Bay Company’s Northern Department of Rupert’s Land held at York Factory, this resolution was passed:

“The Establishment of Fort Garry being in a very dilapidated state—its situation not sufficiently centrical—most exposed to the Spring Floods—and very inconvenient in regard to the navigation of the River, and in other points of view, it is Resolved, 51st—That a new Establishment to bear the same name be formed on a site to be selected near the lower end of the Rapids—for which purpose tradesmen be employed, or the work done by contract as may be found most expedient, and, as Stones and Lime are on the spot those materials to be used instead of timber, being cheaper and more durable.’’

The reference in this resolution to the inconvenience of the site of Upper Fort Garry for the navigation of the river relates to the decked vessels in use at that time between Norway House and Red river. These vessels could not ascend the St. Andrew’s rapids. The “other points of view’’ mentioned in the resolution no doubt mean that the new site would have an advantage over the old one in the event of domestic or foreign attack; there was some unrest among the French halfbreeds at this period and questions connected with the boundary line awaited amicable settlement.

That the construction of the fort was proceeded with at once is apparent from a letter from Governor George Simpson to the Governor and Committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, London, dated York Factory, 18th July, 1831; paragraph 17 of that letter is as follows:

“The Establishment of Fort Garry is in a very dilapidated state, so much so as to be scarcely habitable, and lies so low that we are every successive spring apprehensive that it will be carried away by high water at the breaking up of the ice. It is moreover very disadvantageously situated, being about 45 miles from the lake and 18 miles above the Rapids. I therefore determined last Fall on abandoning that Establishment altogether, and instead of wasting time, labour and money in temporary repairs of tottering wooden buildings, to set about erecting a good solid comfortable Establishment at once of Stone and Lime in such a situation as to be entirely out of the reach of high water and facilitate any extensive operations connected with craft and transport which may hereafter be entered into, and accordingly selected the most eligible spot in the Settlement about 20 miles below the present Establisht, laid the plan and commenced operations without loss of time, and I had the satisfaction of seeing the walls of the principal building nearly up before my departure, and hope to see New Fort Garry (the only stone and lime—and I may add the most respectable looking—Establishment in the Indian country) occupied next spring.

“The expense of this building is little more than the provisions consumed by the workmen, as the principal part of the labour is done by Supernumeraries of the McKenzie’s river Fret (freight) Establishment some of my own crew and a few of the young hands who came out by the Ship last Fall, none of whom could have been so advantageously employed anywhere else.

“I had not an opportunity of consulting your Honours before entering upon this work, but trust it will meet your approbation.”

Building the Fort

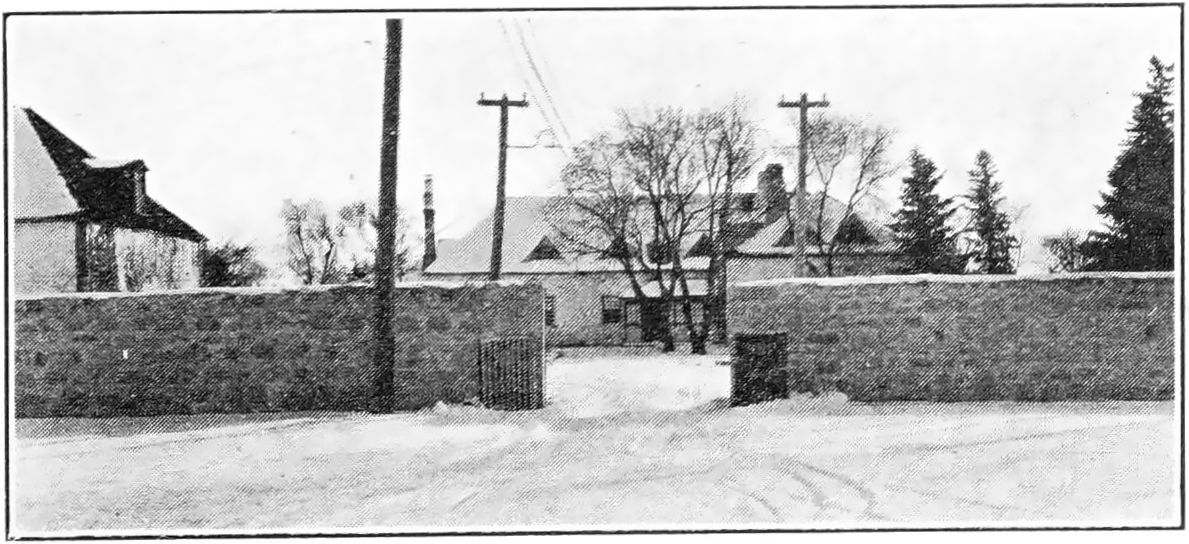

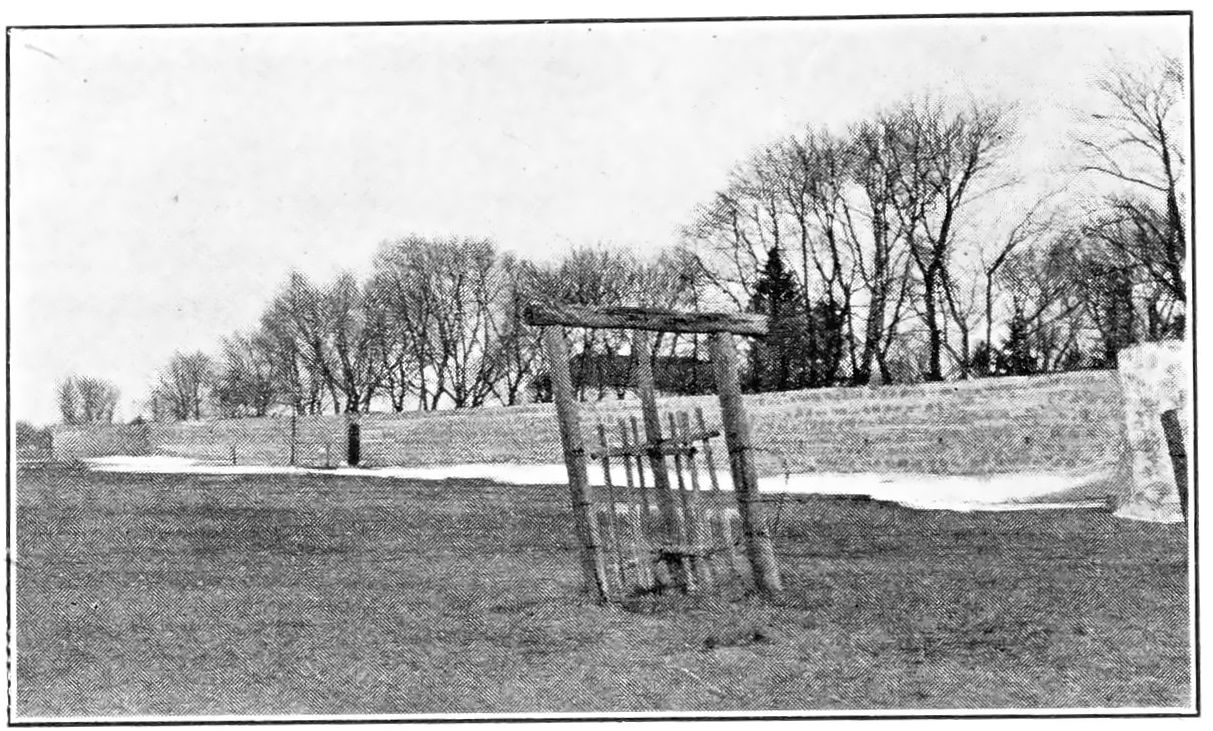

The walls of the fort are of limestone, 3 feet thick, about 7 ½ feet high and, over all, including the bastions, extend for a distance of over 2000 feet; they form a quadrangle, the distance between the opposite walls in each case being about 450 feet. They encompass an area of a little over 4 1⁄2 acres and are loopholed for rifle-fire, with sliding rifle rests made of wood. The bastions, situated at the four corners, are 55 feet in diameter.

Interesting information regarding the building of Lower Fort Garry is contained in the ‘‘History of Manitoba” by the late Hon. Donald Gunn, published 1880:

‘‘The unceasing turbulence of the French halfbreeds, made Governor Simpson desirous of removing his residence from their immediate vicinity at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. He decided on building a fort twenty miles farther north on the Red river. For the purpose of carrying out his intentions, he took his workmen to the most eligible spot on the Red River for the erection of a stone building, and they commenced operations in the month of October, 1831, digging foundations, quarrying stones and preparing timber. The river bank is from thirty to forty feet high, composed of fossiliferous limestone within a distance of a hundred yards from where the buildings were to be reared, and stones from the same place were burned into lime, the unbroken forests on the east side of the river furnishing abundance of fuel for that purpose.”

In another letter to the Governor and Committee dated York Factory, 10th August, 1832, Governor George Simpson reports the rapid progress made in the building of the Fort:

‘‘The new establishment of Fort Garry is in such a state of forwardness that we shall remove into it at the close of the present season, and very much was it required, as the old establishment is no longer habitable, being in a ruinous condition, and so defenceless as to afford no protection either for lives or property. The nominal expense of this new establishment will be heavy but the real cost a mere trifle considering the extent of the buildings…

…In twenty years the real expense will be cleared by a saving in the article of firewood alone, which, owing to the wretched condition of the old establishment, has ever since the year of the inundation been a very heavy item of expense, rarely under £100 p. annum.”

The Hon. Donald Gunn also refers to the occupation of the fort by the Governor of Rupert’s Land:

“During the summers of 1832 and 1833 a commodious dwelling house and a capacious store were finished, and Governor Simpson and family passed the winter of 1833 and 1834 at the Stone Fort. Goods were sold at the store to the settlers inhabiting the north end of the colony, thus doing away with the necessity of travelling over many miles for the purpose of purchasing their trifling supplies. To which we may add, that it being always a place of some importance, but more so when the Governor wintered there, it afforded a market to those who lived in its vicinity. In 1839 a stone wall was commenced, designed as a defence; this structure was three or four feet thick, with embrasures for small arms in it at regular distances of fifteen feet from each other. A capacious round tower occupied each of the four angles. The circumvallation forms a square, with a gate on the south-east side which lies parallel to the river, and another gate on the north-west side which fronts the plains.”

The introduction of stone and lime for building purposes in the Red River district is detailed with enthusiasm by Alexander Ross in his book, “The Red River Settlement,” published in 1856:

“The more solid structures of stone and lime are also in some few instances beginning to be introduced by the Company. … In the upper part of the settlement where wood may still be got, stone is not to be found; but in other places, towards the lower end, lime stone quarries are abundant. Lime was made here as early as the time of Governor Bulger; but the article was only used for practical purposes, such as building and the whitewashing of houses, very lately. The first instance was at the building of a small powder magazine, erected by the Company at Upper Fort Garry in 1830. This magazine claims the proud distinction of being the first stone and lime building in the colony.

“In the year following, the Company commenced building on an elevated spot at the head of the sloop navigation, 20 miles below the forks . . .an establishment of stone and lime on a large scale, intended as a stronghold and safe retreat from any foreign enemy, or the destructive visitation of high water—should such a catastrophe ever occur again.

“This establishment, called Lower Fort Garry, covers about as much ground as St. Paul’s Cathedral, in London. It was at first designed as the seat of Government, and the Company’s head depot; but that intention has been relinquished in favour of Upper Fort Garry, situated about 400 yards above the confluence of the Assiniboine and Red Rivers, in latitude 49° 53’ north and longitude 97° west; a situation more central than the former and certainly better adapted both for defence and the transaction of business pertaining to the colony.

“These splendid establishments, for such they really are in a place like Red River, impart an air of growing importance to the place. Upper Fort Garry, the seat of the colony Governor, is a lively and attractive station, full of business and bustle. Here all affairs of the colony are chiefly transacted, and here ladies wear their silken gowns and gentlemen their beaver hats. Its gay and imposing appearance make it a delight of every visitor and a rendezvous of all comers and goers.

“Lower Fort Garry is more secluded; although picturesque, and full of rural beauty. Here the Governor of Rupert’s Land resides, when he passes any time in the colony. To those of studious and retired habits, it is preferred to the Upper Fort.”

Paul Kane, in his book “Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America,” makes mention of his arrival at the Lower Fort on 13th June, 1846, and its importance at that time as a meeting place of Sir George Simpson and his council:

“We entered the mouth of the Red River about ten this morning. The banks of this river, which here enters the lake, are for five or six miles low and marshy. After proceeding upstream for about twenty miles, we arrived at the Stone Fort, belonging to the Company, where I found Sir George Simpson and several of the gentlemen of the Company, who assemble here annually for the purpose of holding a council for the transaction of business.”

Duncan McRae: A Builder in Stone

The stone-mason responsible for the building of walls and bastions of Lower Fort Garry, and possibly for some although not all of the stone houses there, was a Scot named Duncan McRae, who in the year 1837, at the age of 24 years, left his home in Stornoway, in the Scottish Hebrides, for service with the Hudson’s Bay Company, and reached Fort Garry in the early spring of 1838.

Closely associated with him in his work was John Clouston, another Hebridean stone-mason who emigrated from Scotland at the same time.

McRae also built the stonework of the Upper Fort when it was reconstructed. Only the old gateway of this building remains today. It was preserved during the demolition of the Upper Fort in 1882, and, along with the little Fort Garry park on which it stands, was presented to the City of Winnipeg by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1897. The park is situated on Main street, near Broadway.

The stone construction of the two forts, Upper and Lower Fort Garry, occupied Duncan McRae for almost ten years. The stone was quarried in the proximity of the Lower Fort site and that required for the Upper Fort was hauled during the winter months up the Red river in sledges drawn by oxen. Loading and unloading was affected by native labour. A box of stout rough boards was used to raise the stone into place and this box was lifted with a windlass and block and tackle. The actual building work was all done during the summer months, the men camping by their work in the evenings and going home on Saturday nights for the week-ends.

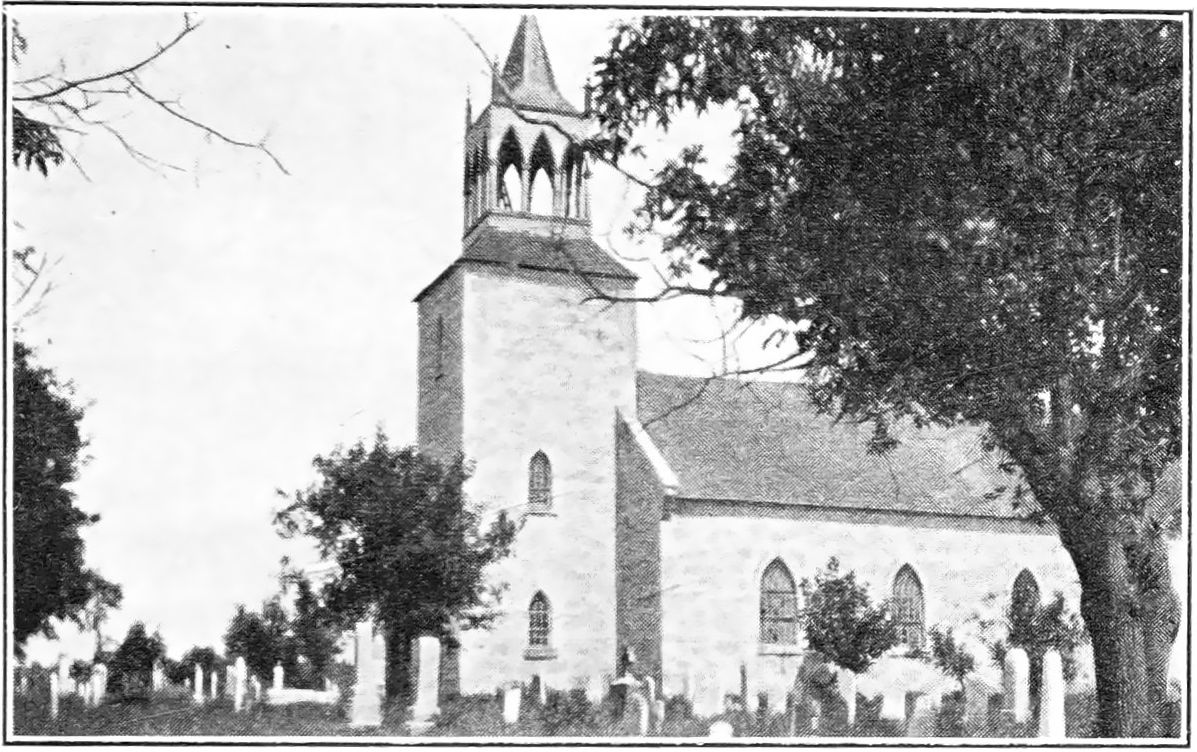

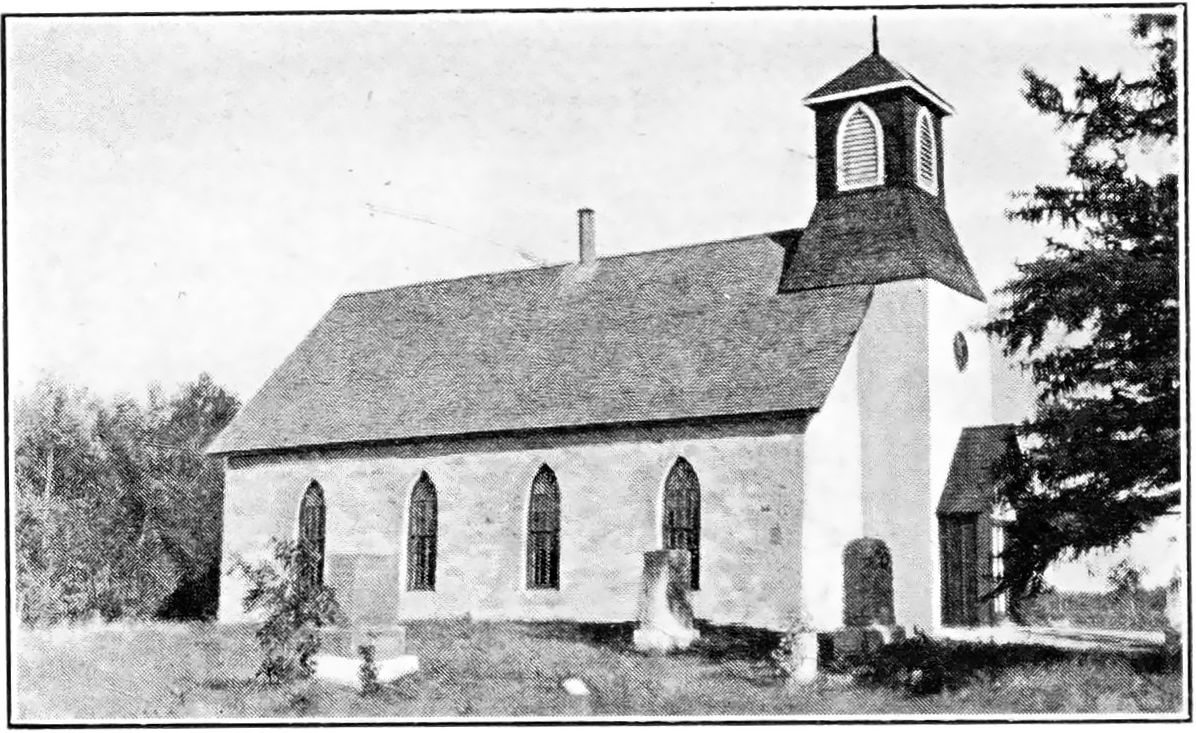

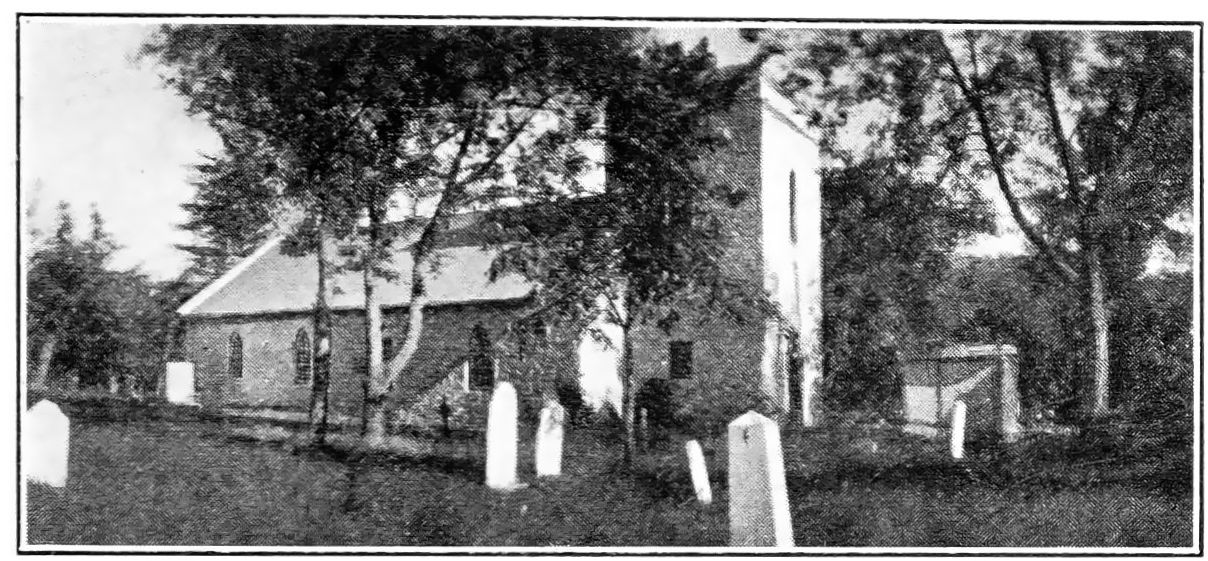

Duncan McRae was responsible for the construction of many of the old stone-built landmarks on the Red river still in existence; St. John’s cathedral, Kildonan church, Rapids church (now known as St. Andrew’s church and situated about half a mile south of St. Andrew’s locks) Mapleton church, the Donald Murray home in Kildonan, Mrs. Davies’ ladies’ college (now the John Black Hall in Kildonan) and Archdeacon Cowley’s church (now St. Peter’s hospital) are all fine examples of the handicraft of this sturdy old pioneer.

During the building of Rapids church, Duncan McRae slipped and injured his leg. A few years later, in his seventieth year, he became an invalid. He died fifteen years later in 1898.

The Fort’s Interior

Upper and Lower Fort Garry were named after Nicholas Garry, Deputy Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1822 to 1835, who accompanied George Simpson to Rupert’s Land in 1821. Finding a bitter feeling still existing among the old rival fur traders, it was decided to abandon many of the old forts of both the North-West and the Hudson’s Bay Company. By order of Governor Simpson, Upper Fort Garry, previously Fort Gibraltar (North-West Company) was rebuilt and named after the London Deputy Governor, Lower Fort Garry taking the same name when it was built later with the intention of abandoning the Upper Fort for the more favourable northerly location.

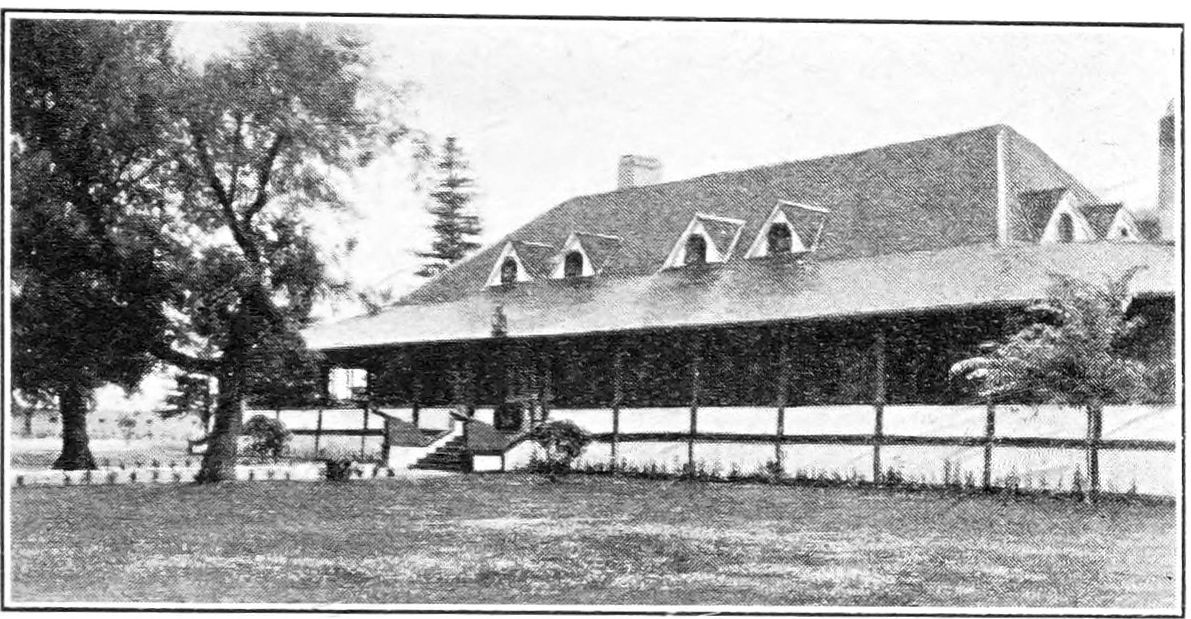

Within the grey, lime-stone walls of Lower Fort Garry there still stand the store and fur warehouse, the quarters of the officers and the men, the old penitentiary with its barred windows, the remains of the prison stockade, and the bake-oven built by the prisoners, the women’s asylum, and the foundations of the barracks of Colonel Wolseley’s soldiers of the Second Quebec Regiment who occupied the fort at the close of the Riel Rebellion of 1870. On the pillars of the east gateway the names can be read of many of the members of the Wolseley Expedition, carved there by the men themselves. Occupying the centre of the quadrangle (at one time encompassed by an inner fence, of which the old gateway still bars the pathway to the eastern gate) is the governor’s residence, with its old-fashioned rooms, quaint fireplaces and heaters, and its underground cellars sectioned off in a bewildering manner. Guarding the main entrance are two muzzle-loading three-inch cannon, dated 1807 and 1810. These old weapons point across the Red river, on whose rapid waters the merry shouts and chansons from the brigades of York boats rang as they raced for the landing place at the creek to the south of the fort. The light-hearted men of the rivers and forests, bringing in their winter’s catch of furs from the distant outposts, hurried in anticipation that, ahead of each crew, before they carried back supplies to the lesser trading posts in the wilderness, there lay a few days’ enjoyment: the meeting with old friends and sweethearts, feasting and merry-making. Dancing, popular then as now, from seven in the evening till nine o’clock the next morning, formed their chief entertainment. They never wearied of dancing to the music of Alfred Franks’ fiddle and Murdo Reid’s bagpipes, or of others playing the music for the old dances still dear to the hearts of the old-timers of the Red River—the Eight-Hand Reel, Double-Jig, Drops o’ Brandy, Duck Dance, Rabbit Dance, Kissing Dance, Canadian Quadrilles, Polka, Schottische, Highland Fling, and the popular Red River Jig.

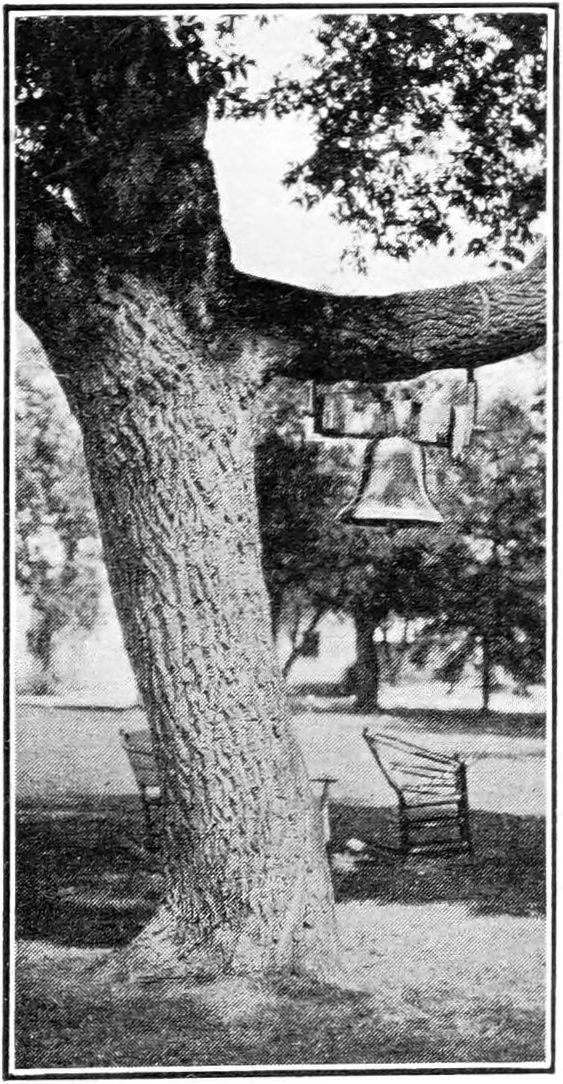

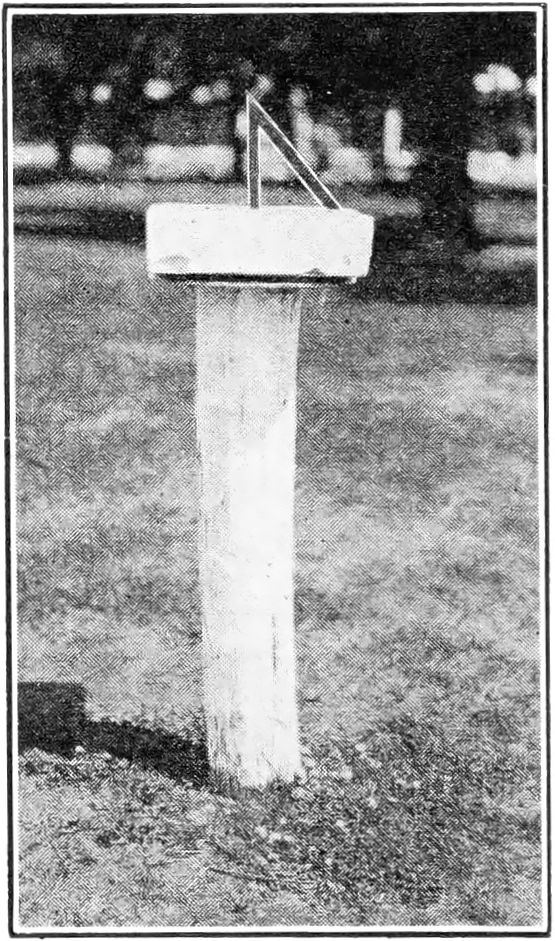

From a tree in front of the residence there hangs the bell, dated 1850, whose melodious tone signalled to all within the walls of the fort the hours of labour and refreshment, fire, flood and other eventful happenings, the hour of worship, the passing of the old year and the birth of the new, and sometimes tolled the death of an old friend. On the lawn, to the immediate south of the residence, an old weatherbeaten limestone sundial rests on a wooden block. It was set there probably as far back as the time of the building of the fort by men whose unerring clock was the sun, the moon, and the stars.

Neatly kept lawns, flower beds, rustic chairs, and shady maples and pines under which ladies shelter and sip tea in the heat of a summer afternoon; cannons, loop-holed walls and bastion strongholds, and outside, parked automobiles where once were teepees and bands of trading Indians, then just beyond the south wall, a modern golf course where the balls hum over grass-covered ruins of the old blacksmith’s forge, the grist mills, the lime kilns and the dwelling houses which once were there but are now no more—all indicate the change from the old order.

Historical Importance

Lower Fort Garry might be looked upon as a monument to the union of the North-West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company, which, after many years of competition, took place in 1821.

The extensive powers granted by the Royal Charter of 1670 to the Hudson’s Bay Company gave the Company an important place in the affairs of the western hemisphere. Lower Fort Garry became, for a short period, an official as well as a social centre. It was the seat of government and the residence of Sir George Simpson, a picturesque and dominant figure, and governor of a great territory.

Strange gatherings have taken place within the Stone Fort. Interesting history could indeed be written if the old walls could only speak. In the days of Sir George Simpson, when a Council was called, great personalities would foregather from the ice-bound Mackenzie, from the sunny slopes of the Pacific, from the shores of Hudson Bay; keen, determined, virile factors would arrive within a few days of one another, sometimes within a few hours, so well did they gauge the time. Here at Lower Fort Garry, in the Council room hardly twenty feet square, also at Upper Fort Garry, at Norway House and at Fort Carlton, those far-travelled, far-sighted fur traders would determine the welfare of a race, the destinies of a nation in embryo, the business of half a continent; and they were eminently capable of governing, for in their own territory they ruled over a land greater in extent than the country that gave them birth.

It was at Lower Fort Garry that the great annual brigades of boats would meet, exchange supplies, furs, tools, guns, articles of trade and letters. The officers of the brigades housed in quarters, the voyageurs camped on the lawn within the walled enclosure—while by the shore at the creek to the south of the fort lay the brigades of York boats and canoes on whose return the comfort and happiness of the dwellers in many lonely forts in the vast up-country so greatly depended.

It was to the Upper Fort and also to Lower Fort Garry, on a secret mission, that Colonel Crofton came in 1846 in command of a wing of the Sixth Foot, a detachment of Artillery and Royal Engineers, Sappers and Miners, in all 329 men, 18 officers, 17 women and 19 children, with one nine-pounder cannon and three six-pounders; the force remaining for a year.

It is interesting to note that Colonel Crofton in his evidence given before a Committee of the House of Commons in 1857 mentions that “beef cost 2d per lb. and there was no want of flour.”

Of the “secret mission” Dr. George Bryce writes in “The Remarkable History of the Hudson’s Bay Company”:

“During this year (1846) also the Oregon question threatened war between Great Britain and the United States. The policy of the British Government is, on the first appearance of trouble, to prepare for hostilities. Accordingly the 6th Royal Regiment of Foot, with sappers and artillery, in all five hundred strong, was hurried out under Colonel Crofton to defend the colony. Colonel Crofton took the place of Alexander Christie as Governor. The addition of this body of military to the colony gave picturesqueness to the hitherto monotonous life of Red River. A market for produce and the circulation of a large sum of money marked their stay on Red River. The turbulent spirits who had made much trouble were now silenced, or betook themselves to a safe place across the boundary line.”

Fishing at the Stone Fort

In his “Notes of the Flood at Red River in 1852,” David Anderson, D.D., first Bishop of Rupert’s Land, throws a side light on life and conditions prevailing at the Lower Fort. The small creek at the side of the fort (really south of the fort itself) to which he refers has long been dry but the bed is plainly visible. At the side of the bed, there runs a spring of clear crystal water which has never been known to freeze, even in the coldest weather. This spring supplied the fort with fresh water for many years:

“My sister and I,” states Bishop Anderson, “started for the Stone Fort at 6 a.m. … At St. Andrews we called to see Mr. and Mrs. Hunter and from there drove our own horse down to the Lower Fort. . . . Here we found a changed scene. The Fort has been improved with much taste by the Governor and Mrs. Colville and it began to wear much more of an English aspect; the annuals were above ground and the lawns smooth and green. Its chief recommendation in our eyes, in the circumstances, was that it still stood on a high bank thirty feet above the river. The fishing was going on vigorously. We watched Indians taking the goldeyes with a scoop, something like a shrimp net, with a long handle. With it they got a single fish, now and then three or four times in succession; at other times they brought up as many as two or three at once. These the Indian threw over his head and they were immediately killed by his wife, who sat higher up the bank. They had in this way caught 300 in one day. A few sturgeon had been taken in the small creek at the side of the Fort. The rapidity of the current almost made one giddy to look at it. It was running at the rate of eight or ten miles an hour.”

Experimental Farming

In compiling the story of Lower Fort Garry, a hundred years after its erection, one must naturally refer to the material that has been written from time to time by those who have gone before, those who were participants in or eye-witnesses of the events that took place during their particular period of sojourn in the district; sometimes a page must be quoted, at other times a paragraph, possibly only a phrase, narrating a series of happenings, a single incident, perhaps merely a gesture, but we must have their reference to produce a finished picture.

An apprentice clerk named Roderick Campbell was employed at the Lower Fort during A. R. Lillie’s regime. This young man was a keen observer, deeply interested in the study of Indian languages, in farming and in floriculture and, in a book little known probably because of its title, ‘‘The Father of St. Kilda,” he has left a store of amusing and informative material pertaining to life in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Red river, during the period 1859 to 1877. Campbell recounts in his work the attempts made to farm on a large scale at Lower Fort Garry and describes the many varieties of wild flowers that raised their colourful heads to the warm sunshine and bright skies of Assiniboia almost before their slender roots had broken from the grip of the frozen soil. Of the period around 1859 he writes:

“A very large farm had been brought under cultivation in the immediate vicinity. . . . The experiment in agriculture proved most encouraging, and the harvest was everything that could be desired. The golden-tinted wheat, the plump round barley, the capital potatoes and turnips, soon showed the fertile capabilities of the Red River Valley.

“Wild fruits were never lacking, gooseberries, strawberries, raspberries, plums and different varieties of currants of excellent flavour. Wild flowers and blossoming shrubs bloomed in the woods and prairies as soon as the snow melted. Foremost were the anemones, which covered the yet frozen prairie with a lovely carpet of colours, each flower being provided by nature with a tiny cloak, which the slender blossom draws around it for protection when the winds are chill. And one might walk all day through fields of magnificent lilies. The red and June cherries were the first to put on their garlands, and then the woods were white with the profusion of their blossoms. The hawthorn followed—a dwarf tree—but so loaded with bloom that each seemed one single nosegay. But the spirea was the most beautiful of all, with its pink and white cone-shaped flower clusters poised on every branch. Honeysuckles adorned the prairie; hops grew in abundance in the woods; winter berries, the partridge’s favourite, grew in wood and plain alike.”

Everyday Life

Roderick Campbell had so much of interest to say of the life in the service generally and of the conditions prevailing at Lower Fort Garry at this period of its history when so little seems to have been written by others in regard to it, that one is tempted to quote him frequently in this brief history. The following is a reference which could hardly be omitted:

‘‘Lower Fort Garry, as I found it in 1859, certainly showed outward signs of future prosperity, however misty its past history might have been…

…The residents in the Fort formed a very lively community by themselves. They had regular hours for the dispatch of business, and afterwards, to beguile the tedium of the long sub-Artic nights, they met together for a few hours’ jollification, when old Scottish songs were sung in voices cracked and sharpened by the cold northern blasts…

‘‘The fort stood in the middle of a two-mile reservation on the river bank. Outside of this limit many of the Company’s retired servants had settled, each on the plot of land given him to work and live upon. Among them, too, there were boisterous evenings… My emporium was crowded every day with customers ready to purchase goods for cash, or to barter with their furs and agricultural produce. A record of all articles sold was entered in a sales book. The currency was sterling, and consisted chiefly of promissory notes issued by my Company, redeemable by bills of exchange granted at sixty days’ sight on the Governor and the Committee of the Company in London. These bore a high premium in the United States. The notes were of two denominations, one pound and five shillings. Besides the notes there was a good deal of English gold and silver in circulation. Even in that remote isolation unexpected evidence of civilisation occasionally met my eyes. At my landing upon the river bank I saw an old Englishman engaged in the proud avocation of collector of customs for the colony. In this exalted capacity he resided here during a certain portion of the year to watch the boats passing in and out and to make certain clearances of a primitive character, the total being £2,000, of which my Company paid about £700. There was no better authority not only on the colony, but on the country than this aged and respected collector of customs. To him everybody who wanted information had recourse. He told me he came to the country in 1813, and to the then very small and young Scotch colony in 1824 after an abrupt dismissal from the service. He had married two native wives, and had a family of twenty-two children. He was a sort of universal factotum, and acted by turns as catechist, schoolmaster, precentor, farmer, clerk to the council of Assiniboia, and occasionally when required as administerer of oaths, besides the business already referred to…

Northern Packet and Other Transport

“Travelling on horseback” *(on the trail between Upper and Lower Fort Garry) “was the only mode of locomotion, except the famous ‘Red River cart,’ made wholly of wood, and the only home manufacture in the colony worthy of special notice. What the birch-bark canoe was in the North, this marvellous native conveyance was here. To construct it, only an axe, saw, drawknife, and screw auger were needed, and it carried one thousand pounds for as many miles. It is designed specially to traverse such enormous stretches of prairie as lie between the fort and the Rocky Mountains.*

“After some skirmishes between autumn and winter, snow and frost laid hold of the ground sufficiently to enable the annual northern packet to leave the fort for the northern districts. The first stretch was three hundred and fifty miles over the ice on Lake Winnipeg to Norway House. The party set out on 10th December, and the means of transit were in the first place sledges, drawn by splendid dogs, and in the second snowshoes. These sledges (of Indian design) were drawn by four dogs to each, and carried a burden of six to seven hundred pounds. With such a load they travelled forty miles a day. …At the end of the first stage the packet was overhauled and repacked, one portion for the Bay, the other for the Saskatchewan and the far-off Mackenzie districts. For this, new sets of packet-bearers travelled eastward, westward, and northward, while the first stage party returned to the fort with the packet from the Bay. Not till the end of the following February did the packet-bearers from west and north reach us overland by Fort Carlton, on the great Saskatchewan River. As for news from the outside world, that was as impossible for us, at least at this season, as from the planet Jupiter.

“The country was entirely self-sustaining, and in its supply of fish, flesh and fowl had probably no equal in the world.

“The autumn white fishing was another important annual event. Millions of these excellent fish were thus secured, hung on spits to be frozen, and then carried home on sledges to be distributed free of charge to the colony.

“It was in 1861, too, that a small steamboat first plied upon the river. The Indians hated and feared it, seeing it going miraculously without oars or sail, and called it a “water-devil,” motioning it back with incantations and exorcisms. Its career was short, however, as it sank in its winter berth.

“On 18th May our new Governor, A. G. Dallas, Esq., arrived at Fort Garry, a man so extraordinarily tall and thin that it was one of our irreverent jests to say that he was one who compelled a second look, if only to see to the top of him. He brought a piper with him, and the unfamiliar strains of music, the ribboned pipes, and the player in feathered Glengarry and the garb of Old Gaul, brought crowds of savages to gaze with wonder at the novel spectacle.”

The Trail Between the Forts

Although built for protection and while bands of Indians were continuously encamped around its sturdy walls, Lower Fort Garry never heard the sound of a hostile shot and never against those grey walls did an arrow point break—a “Sermon in Stones” testifying to the wise administration of its occupants, who lived up to the spirit and tradition of the race of shepherds, crofters and covenanters from which they sprang.

No more lucid description of the trail leading from the Upper Fort to the Lower Fort can be found anywhere than in Hargrave’s “Red River” dealing with the period round 1861:

“The Tuesday after my arrival, the company of Canadian riflemen, already referred to, left Fort Garry to proceed to Canada via York Factory. Along with Mr. McMurray, a gentlemen in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company, I rode down to Lower Fort Garry to see them off. This place is about twenty miles distant from the Upper Fort, the well-beaten high road already mentioned connecting the two places. After passing St. John we rode through a well cultivated country. About five miles from the Fort, at a place called Frog Plain, stands the Scotch Church, the central point of the Scotch Settlement. Here the houses are numerous; in general they are very small, but now and then we passed a comfortable looking roomy dwelling. The English Church of St. Paul came next in sight. It was built of wood, and adjoining it were a school house and parsonage. On our left hand extended a vast unenclosed common called the Image Plain. About half way between the Forts, we came to a couple of bridges near each other spanning two deep ravines. Close to the second of these stood a solitary water mill, tenantless and forsaken, looking the embodiment of desolation. It had long been totally deserted as useless in consequence of a want of waterpower.

“At this part of the settlement no attempt had been made to enclose any ground on the Plain side of the road, although the river side was cultivated and settled. After a further ride of about two miles, we entered woods which henceforward extended all the way down to the lower end of the Indian Settlement, comprising a space of fully fifteen miles. The road runs through these the whole way, and no house is visible for a long distance except at one spot where, through a long vista in the woods, St. Andrew’s Church rears its spire-crowned tower, and the closely clustered whitewashed houses of the St. Andrew’s Rapids settlement loom in the distance.

“About half a mile from the Lower Fort that establishment becomes visible, and the country is for a short space more clear of trees. Several very comfortable private dwelling houses exist hereabouts, and some of the wealthier residents have from time to time inhabited them. The spot has, from the date of its original settlement, been called “Little Britain.” The district between the two Forts may be called the grain country of the settlement, no other region within the municipal boundaries of the colony being on the whole so well cultivated or inhabited by settlers so entirely devoted to agricultural occupations.”

Historic Happenings

At Lower Fort Garry scientific observations, astronomical, meteorological, agricultural, etc., were made and maintained for the benefit of science in Western Canada. It was the starting point, during four decades, of scientific tours and journeys of discovery by many distinguished explorers who obtained their equipment from the fort’s ample stores or spent a few hospitable nights before taking their long and adventurous journeys to the north or west.

Lower Fort Garry was the holiday resort of many of the prominent officers of the Company for thirty years. Sir George Simpson and the late Alexander Grant Dallas lived there for a time. Many of the Governors-General of Canada visited the fort. In its sitting room were settled the final details of the Franklin Relief Expedition which was conducted overland to the shores of the Arctic by Dr. Rae, an officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company who was honoured by the British government with the Arctic medal for his work in Arctic exploration.

A body of British army pensioners was quartered at Lower Fort Garry in 1848. In 1857 the pensioners were succeeded by another military force of 120 men of the Royal Canadian Rifles. This detachment remained in the Red River country until 1861.

Throughout the Far North and by the firesides of the old-time settlers on the Red river, there are many stories and traditions connected with the Stone Fort. Expeditions started from Lower Fort Garry and added largely to the geographical knowledge of the continent.

Robert Kennicott, of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, U.S.A., left Lower Fort Garry in 1859 for the valley of the Mackenzie, where he remained for three years, enriching thereby the collections of the institution he served.

The high bank upon which Lower Fort Garry stands has been the scene of strange and picturesque happenings since that distinguished and intrepid explorer, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes Sieur de la Verendrye reached lake Winnipeg in 1733.

On several occasions the Red River district was visited by plagues of locusts. In the years 1864 and 1865 their visitation is said to have been equalled in intensity on only two previous occasions, 1818 and 1857.

In 1864, millions upon millions of these pests stripped the entire country of every green blade of vegetation, then left behind them, for the next summer to incubate, still more countless millions of eggs, which came to winged life in due season, repeating with even greater severity the previous year’s disastrous ruination of crops, and when the vegetation failed them they turned and destroyed themselves, leaving everywhere heaps of their dead which had to be gathered up in cart loads and dumped in the river.

The afflicted people on the banks of the Red river must surely have wondered at times if they had incurred the anger of the Lord, as did Pharaoh and the Egyptians of old on the shores of the Red Sea:

“And the locusts went up over all the land of Egypt, and rested in all the coasts of Egypt: very grievous were they; before them there were no such locusts as they, neither after them shall be such.

“For they covered the face of the whole earth, so that the land was darkened; and they did eat every herb of the land, and all the fruit of the trees which the hail had left: and there remained not any green thing in the trees, or in the herbs of the field, through all the land of Egypt.” (Exodus, Chap. 10, verses 14 and 15).

Social Amenities and Customs

We are indebted to Isaac Cowie for a further word picture of the Lower Fort, its delightful surroundings and its still more delightful people, in his “The Company of Adventurers,” in which he describes his trip there prior to the disturbing influences of the Riel Rebellion:

“After York Factory had ceased to be the regular meeting place, the Council came to be held usually at this place (Norway House) and only occasionally in Red River Settlement at Lower Fort Garry.

“We landed in the marsh at the mouth of the Red River on the 1st of October (1867). It was a glorious morning, in fact after we left the Hayes River till my arrival at Qu’Appelle, and long after, the weather was without a flaw, and I do not remember to have since enjoyed a more prolonged and beautiful autumn. Ducks were flying about, and the pot hunters were busy at their harvest, but we had no time for sport, everyone being eager to reach the end of the journey at Lower Fort Garry.

“We started under oars, boat racing against boat. When we got out of the marshland and reached the dry banks of the river, the men strung out on the line ahead, and went lightly as if the St. Peter’s girls had got hold of the towline too. Joyful cries of greeting were exchanged as we sighted and passed the comfortable cabins of the Indian settlers along the river, and we could see that a procession was following us to the fort by the road further back.

“The men were not long unloading the boats and carrying the cargo uphill to the warehouse in the fort. And then, being now united with their families and friends, they eagerly entered the shop to be paid off.

“The Company’s officers stationed there (Lower Fort Garry) were Mr. George Davis, in charge, Mr. Alexander S. Watt, an accountant, and Mr. E. R. Abell, engineer of the steamboat International, and of a mill outside the fort. Staying there, preparing to start for Montreal, were two gentlemen who had lately arrived by the Portage la Loche brigade from Mackenzie River, Messrs. C. P. Gaudet and Thomas Hardisty. Mr. Gaudet was on leave for a year, after sixteen years’ service in the north, and was taking his family to see his friends in Quebec. Mr. Hardisty was being transferred to the Company’s office in Montreal.

“Besides these we saw at the lower fort, retired, Chief Trader A. H. Murray, a fine, genial and accomplished Scot; Mr. Thomas Sinclair, a very popular native magistrate and counsellor of the colony; and the Rev. J. P. Gardiner, of the English Church at St. Andrew’s. My friend Hardisty got a buggy and we went up to the rapids to call on Chief Trader Alexander Christie, father of my shipmate. On the way we met two young ladies going to the fort—the daughter and the niece of Mr. Christie, then attending Miss Davis’ admirable seminary at St. Andrew’s, and qualifying for the position they afterwards so well filled as wives of chief factors.”

On July 3rd, 1868, the Red River was visited by a severe hurricane, which did very considerable damage to property. A barn that was being rebuilt south of the fort almost directly west of the Abell cottage was blown down, killing George Stephens of St. Peters, while one of the Company’s York boats at the boat-building house south of the fort was blown over the fort and rested on the barns beyond the north wall, a distance of well over 500 feet.

The church of the Holy Trinity, then under construction, was torn from its foundations, and Peter Matheson, asleep there at the time, was killed.

The spire of St. Andrew’s church was blown through the roof of the main building, while other roofs were torn off, and fences and buildings carried away and displaced.

The social life at the Lower Fort during the sixties and seventies was of a simple character. Select assemblies of the ladies and the young dandies of the fort and district were held frequently. Many also attended the Penny Readings held periodically in the parish school house, close to the St. Andrew’s Anglican church; occasionally travelling showmen, sleight-of-hand experts, ventriloquists and magicians helped to pass an otherwise idle hour.

It was an old winter marriage custom with the local people at and about the Upper Fort to be married in the forenoon and then to start out on a sleigh ride, the bride and groom leading the way in the first cutter, followed by the bridesmaid and best man in the second, and as many of the marriage party as could accompany them bringing up the rear. This cutter drive always included the Stone Fort, when the gates would be thrown open to allow the happy party to make its proud and stately round of the driveways and out again. Marriages in those days were serious affairs, at least to the chief contracting parties. Such visits always created a flurry of excitement within the sequestered confines of the fort.

Riel Rebellion

In 1869, the “Deed of Surrender” was signed by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Riel Rebellion broke out immediately among the halfbreeds of the Red River. During the rebellion, Lower Fort Garry was more or less “in it but not of it.’’ While the Upper Fort was taken possession of by Riel and his followers, and while most of the excitement was at that point, the Lower Fort remained in the hands of the Hudson’s Bay Company officers. It is true Riel could have occupied it whenever he wished, as to all intents and purposes he controlled the whole district, but in consequence of his neglect or indifference, the Stone Fort was used by the troubled loyalists as a place of refuge, where they were practically undisturbed.

Colonel J. S. Dennis, who appears to have been the master-at-arms, was very careful whom he allowed to enter the fort, and it was here that the secret organizing of the loyalists was done and at least some of the arrangements made for the raid planned and started against Riel. In this “affair” the large cannon at the Lower Fort was requisitioned, and was taken away on runners. It was never returned to the Lower Fort.

Probably this was the large cannon to which Roderick Campbell, writing of the events of 1859, refers in the following passage:

“There was one cannon in the fort which looked as old as Mons Meg at Edinburgh Castle, and might have been constructed at the same time by blacksmith Brawny McKinn.”

The raid itself is described vividly by Campbell in his “Father of St. Kilda”:

“(Dr. Schultz) being at liberty, he at once set about inciting the people to violence (against Riel) and was so far successful that even from the far- off Portage la Prairie recruits crowded to his rendezvous in Kildonan church. But shrewdly foreseeing consequences, he refused to accept the responsibility of controlling these misguided people who had gathered at his call—a heterogeneous collection of Canadians, Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, Dutch, Germans, English and Scotch, and their half-breeds, as well as representatives of three distinct Indian races: Crees, Salteaux and Ojibways. Thus, leaderless, purposeless, shelterless (the thermometer stood at 55 degrees below zero), the warlike camp, under the influence of intense frost and intenser fear, disappeared with extraordinary rapidity, vanishing in every direction except that which led to Riel’s quarters in Fort Garry, eight miles off. They had one very ancient piece of artillery with them, which they left behind them ingloriously in their flight.

“It had a serious sequel, however, for Riel secured as prisoners some eighty of Schultz’s soldiers and kept them in durance vile under daily threats of death.

Riel’s Raid on the Stone Fort

The story has been told of a famous midnight interview between Louis Riel and Donald A. Smith (later Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal), a high-placed and trusted officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company, a man of far-reaching personal influence and, at that time, a Commissioner of the Canadian Government appointed to negotiate a settlement of the grievances of the French halfbreeds of the Red River.

The rebel leader is reported to have ridden during the night from Upper Fort Garry to the Lower Fort and, shortly after midnight, to have forced his way into the residence to Donald A. Smith’s bedside. Riel endeavoured to obtain impracticable concessions from the quiet, courteous but determined HBC officer, but without success, and it is said he then rode away from the Lower Fort, back to Upper Fort Garry, with his dream of power broken.

Close investigation hardly bears this out. It is definitely established, however, that Louis Riel, his lieutenants, Lepine and O’Donohue, with a number of followers on horseback and accompanied by sleighs, made a night journey to the Lower Fort, but this was for the express purpose of recapturing Dr. Schultz, whom Riel had sworn to shoot on sight.

The rebels clambered over the south wall, at the place between the southeast bastion and the saleshop. The guard of the fort, consisting of halfbreeds, armed only with flintlocks, fled on their approach, either through fear of Riel or according to a prearranged plan. Seeing the futility of armed resistance, Mr. William Flett, who was in charge, gave instructions to James Franks, a servant of the Company, and to his son Alfred, then a boy of about ten years of age, to stable Riel’s horses in the barn to the north of the fort and permitted Riel to take temporary possession.

Sheriff Inkster, then a grown man and closely in touch with much that took place, in an interview in September, 1926, gave the writer a vivid account of this event:

“It was a beautifully clear, crisp Saturday night, I remember. Riel, Lepine and O’Donohue, with a party of horsemen and sleighs, went overnight to the Lower Fort in search of Dr. Schultz. They first went to John Tait’s house at Parkdale and failing to find Schultz there and suspicious that Tait knew his whereabouts, they took him along with them in the first sleigh to the Stone Fort. On getting to the Fort, Riel forced his way into the residence, where Archdeacon McLean, I think it was, but certainly not Donald A. Smith, was staying overnight. As far as I am aware, Donald A. Smith never spent a night at this time away from the Upper Fort.

“Riel pushed into the Archdeacon’s bedroom, thinking Schultz might be the occupant, pulled the bedclothes roughly from the bed and frightened the Archdeacon nearly out of his wits.

“Meantime, Dr. Schultz, with George McVicar and Monkman (the last a man then over seventy years of age), made his escape to Duluth, although none of them were familiar with the country.’’

While Riel was at the Stone Fort, Dr. Schultz was in hiding in the home of the Rev. John McNabb, situated only three quarters of a mile south, at Little Britain. This house was the property of Mrs. Donald Ross, widow of Chief Factor Donald Ross of Norway House who died in 1852. It was burned down a few years ago. The stone cellar is all that now remains of it.

Donald A. Smith, in his lucid report to the Hon. Joseph Howe, Secretary of State for the Provinces at Ottawa, of the various happenings at the Red River in the latter part of 1869 and the early part of 1870, makes no mention of any midnight interview between him and Riel at the Stone Fort, which, doubtless, he would have done had such a thing taken place. But he does detail a nocturnal visit made to him by Riel at his quarters at Upper Fort Garry and this tallies in so many ways with the one alleged to have taken place at the Lower Fort that it can easily be seen how the error has crept in:

“I took up my quarters in one of the houses occupied by the Hudson’s Bay Company officers, and from that date until towards the close of February, was virtually a prisoner within the Fort, although with permission to go outside the walls for exercise accompanied by two armed guards, a privilege of which I never availed myself.”

Donald A. Smith then describes the request made by Riel for his commission, a document which Donald A. Smith explained was not in his possession. He consented to send a messenger for this document and gives the following account of the interview:

“It was now about 10 o’clock and my messenger having been marched out, I retired to bed, but only to be awakened ’twixt two and three o’clock of the morning of the 15th (January, 1870) by Riel, who, with a guard, stood by the bedside and again demanded a written order for the delivery of my Official Papers, which I again peremptorily refused to give.”

Alfred Franks’ recollection of Riel on that eventful night is that “He was a man over medium height, stout, athletic, with black hair and clear eyes, neatly dressed and polite and manly in his bearing,’’ while Chief Trader W. J. (Big Bear) McLean remembers him as “a fine looking man, strong, stout and about five feet ten or eleven in height, a man who spoke well and was shrewd and clever.”

Roderick Campbell, in “The Father of St. Kilda,” is almost epigrammatic in his description of Riel:

“In the course of my journey I camped at St. Boniface, and there met Louis Riel. He was a fair type of his race, spare, with black hair and blue eyes, neither scrupulously clean nor well dressed. He spoke fluently in Cree, French and English, the last with much of the accent of the others, and had a noble taste in Demerara rum.”

Loyalists’ Place of Refuge

During the rebellion the British halfbreeds remained loyal to the motherland; the full blooded Indians were also not at all in accord with Riel and his followers.

Throughout these troublous times Lower Fort Garry continued to be the unofficial stronghold of the indignant loyalists and it was the scene of more than one escape from the hands of Riel and his rebels.

In W. J. Healy’s book, “Women of the Red River,” that remarkable and fascinating old lady, the late Mrs. Harriet Goldsmith Cowan, in an interview in her ninety-second year, thus records her escape with Dr. Cowan from the Lower Fort:

“In October, 1869, the Red River insurrection began, Dr. Cowan was acting Governor, on account of the illness of Governor McTavish, when Louis Riel, entering with an armed force, took possession of Fort Garry. He made a prisoner of Dr. Cowan. Riel told me I might go, but I decided to stay with my husband. There was a back door to our house, which Riel’s men did not know of, and James Anderson, the storekeeper at the Fort, used to manage to come to it at night and tell us the news during that terrible winter. I was never afraid of Riel until after he shot Scott, early in March. Donald Smith and I stood at a window of our house and saw poor Scott led out blindfolded, to be shot. Soon after that Riel ordered us out of our house, where Donald Smith lived with us, and we had to go to more crowded quarters in another house within the walls of the Fort. Governor McTavish, who was a dying man, was at Fort Garry. He wanted to go to England, and to have my husband go with him. Riel was willing to let the Governor go, but refused to let my husband leave Red River. The Governor and Mrs. McTavish went to England; he died two days after their landing in Liverpool, in July.

“It was in July that my husband and I, who were then living at the Stone Fort, made our preparations for escape. Governor McTavish had prevailed on Riel to let us move down there. My husband went up to Fort Garry two or three times a week; I never knew whether he would be allowed to come back. Mounted men were stationed near the Stone Fort by Riel. When we had all our preparations made and a York boat loaded, we started off for Lake Winnipeg as fast as our crew could row. One of Riel’s mounted men galloped off to Fort Garry, to tell him of our escape, but before we could be overtaken we were out on the lake and on our way northward to York Factory.”

Wolseley Expedition

The 60th Rifles and the other detachment of regulars, including the Abyssinian Battery of the Royal Field Artillery, with Colonel Wolseley in command, reached Lower Fort Garry on the morning of August 23, 1870. Their coming is interestingly described in the “History of Manitoba” by the late Hon. Donald Gunn:

“The troops passed the night on Elk Island, and started at 5 a.m. on the 22nd for the mouth of the Red River, which was reached by the fastest boats about noon. It was hoped that the Stone Fort would be reached before dark, but at sunset it was still eleven miles distant, and the expedition halted for the night, camping on the right bank of the river. Every precaution had been taken to prevent any information of the arrival of the expedition reaching Riel, and with such success that he had not the slightest idea the expedition was so near him. The boats started again at 3.30 on the morning of the 23rd in a drizzling rain, which continued all day and made their journey very uncomfortable. The people along the bank of the Red River now began to know that the expedition had arrived, and it was greeted with discharges of musketry as it passed along. Stone Fort was reached at 8 o’clock, and here a good breakfast had been prepared by the Hudson’s Bay Company officials, and was keenly relished. After breakfast the boats were relieved of all superfluous stores, only four days’ rations being left, and the advance on Fort Garry was recommenced.”

The subsequent events are well known. Riel and his lieutenants lost their nerve and fled across the border to the U.S.A., leaving the Upper Fort open and the way clear for its occupation by Colonel Wolseley and his troops. Without the firing of a single shot, the Union Jack was once more hoisted over the fort.

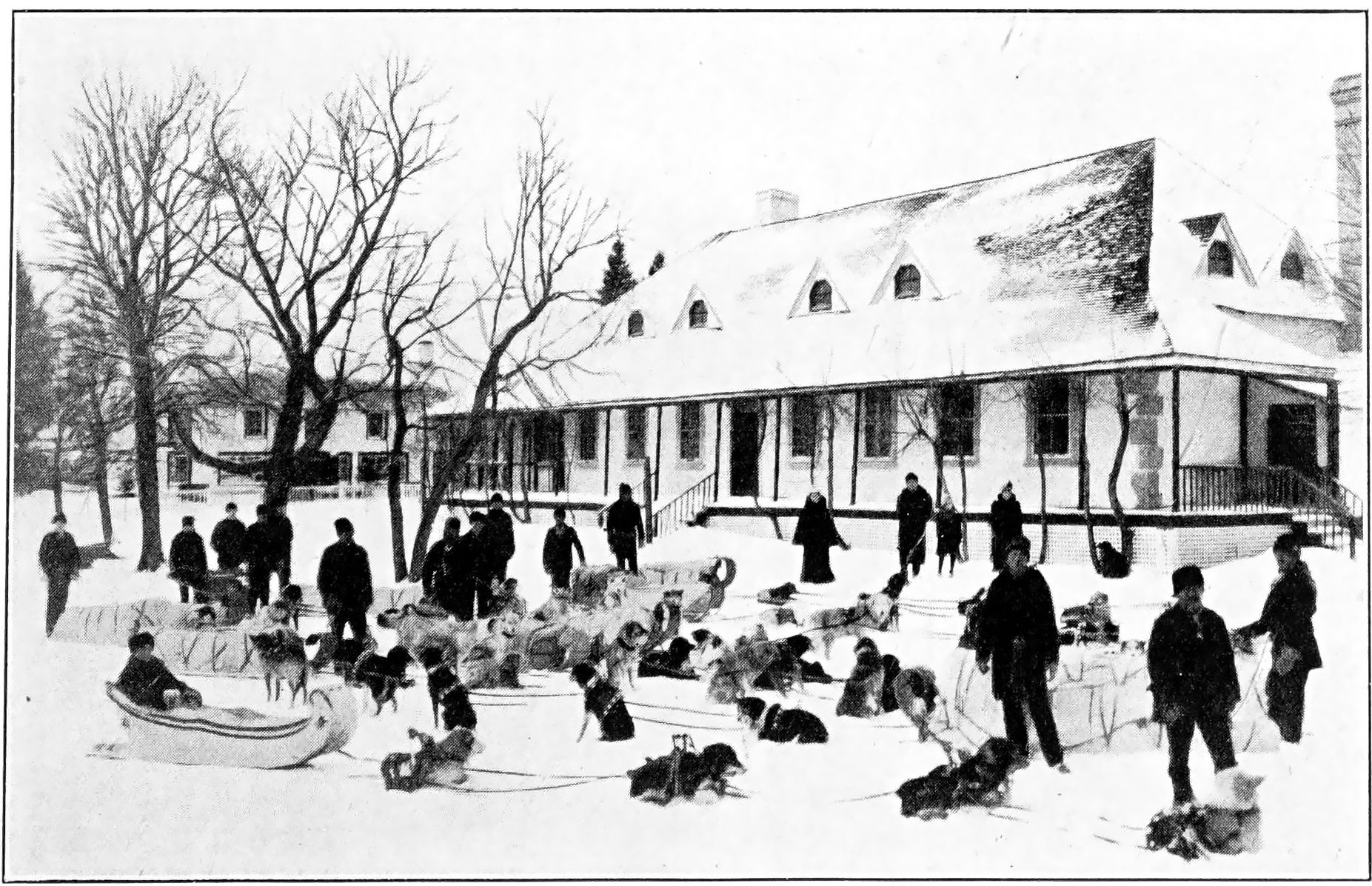

Six companies of the 2nd Quebec Battalion that left Thunder Bay wintered at Lower Fort Garry in 1870.

On arrival they landed opposite the east gate of the Stone Fort. The soldiers lived in tents outside the fort, then later occupied the warehouse (now demolished) to the north of the east gate and immediately south of the northeast bastion.

During the occupation of Lower Fort Garry by the Wolseley expedition, the Masonic Lodge, Lisgar No. 2, was formed by members of the 2nd Quebec Battalion and resident masons in and about the fort.

The lodge was instituted on February 20, 1871.

Its members met at the Lower Fort during the months of February and March, 1871, then later moved to quarters of their own at Mapleton.

The original officers were: John Fraser, W.M.; George Black, S.W.; Thos. Bunn, J.W.; W. J. Picton, S.D.; E. Abell, J.D.; G. H. Kellond, I.G.; W. Lawson, Tyler.

The first masonic picnic in the west was held at the Stone Fort on 24th June, 1871, the chairman on that festive and happy occasion being Bernard Rogan Ross, an officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company, a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and a noted anthropologist and author.

R.C.M. Police and the Stone Fort

The year 1873 saw the formation of the first body of the Royal North-West Mounted Police in this district, twelve men being chosen from each of the Quebec battalions. This body of men had the work of declaring the members elected to Manitoba’s first parliament, which assembled for its first session at the residence of a Mr. Bannatyne, now the site of the Canadian Bank of Commerce on Main street, Winnipeg.

During their first winter, the newly-formed mounted police were quartered at Lower Fort Garry.

Colonel Robertson Ross, the adjutant-general, spent the summer of 1873 in the west and it was he who reported in favour of “a mobile force.”

In his report, Colonel Ross recommended that this force consist of mounted riflemen, and that the men should not wear the sombre regulation uniform such as was worn by the riflemen in the Red River Expedition, as these did not sufficiently impress the Indians, whose critical comments were as follows:

“Who are those soldiers wearing dark clothes? Our old brothers wore red coats. We know that the soldiers of the Great Mother wear red coats.”

They still remembered, or had heard of Colonel Crofton’s red coats of 1846.

And that is the reason why the R.C.M.P. wear red coats.

The Penitentiary

The penitentiary at Lower Fort Garry was created in the fall of 1870 and was the government jail for Rupert’s Land. Colonel Sam. L. Bedson, who served later with Colonel Middleton at the time of the North-West Rebellion of ’85, was the warden in charge. His deputy at one time was a man of the name of Tom Slack, who committed suicide by shooting himself in a room on the top floor of the penitentiary. Very few prisoners ever escaped from Lower Fort Garry penitentiary, as it was well guarded, while, in addition to the stone wall, a wooden stockade running four feet into the ground and probably twenty feet high formed a further protection against escape. The prisoners worked at the north farm at haying and wood-cutting, and stone was conveyed by them from the river bank, in handbarrows, and broken by hammers inside the fort. The remains of this stone pile are still to be seen just east of the penitentiary building.

The grounds, with their fine lawns and beautiful flower beds bordered with white-washed stones, were kept in order by the prisoners.

Inside the penitentiary building, near the entrance, just beyond the stairway, on the left, was at one time a sunken dark cell in which refractory prisoners were lodged. This has now been filled in. Behind that, on the left side, sectioned off, were the individual sleeping cells for the prisoners, both on the ground floor and upstairs. The right side was a general room. This also applied to the upstairs.

The top floor was the prisoners’ dining room.

The asylum and the penitentiary were moved to Selkirk in 1877.

The iron guards now on the windows are the originals. The old spyhole door is still preserved.

No capital punishments were ever carried out at Lower Fort Garry, nor was the fort ever attacked by any hostile force, for after all Riel’s midnight escapade was little more than a surprise visit.

At an earlier date, this penitentiary building was used as a storehouse.

First Indian Treaty in the West

A treaty was made between the Right Honourable Thomas, Earl of Selkirk, and the Chippewa or Salteaux Nation and the Killistine or Cree Nation on July 18, 1817. The first Indian Treaty in the west between the Canadian government and the Chippewa and Swampy Cree tribes was concluded at Lower Fort Garry, just beyond the northwest bastion, on August 3, 1871. This is referred to as “Treaty Number One.”

This treaty is well described in the following extract from Wemyss M. Simpson, the Indian Commissioner, and is referred to in “The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba, the North-West Territories and Kee-wa-tin”:

“…Having, in association with S. J. Dawson, Esq., and Robert Pether, Esq., effected a preliminary arrangement with the Indians of Rainy Lake, the particulars of which I have already had the honor of reporting to you in my Report, dated July 11th, 1871, I proceeded by the Lake of the Woods and Dawson Road to Fort Garry, at which place I arrived on the 16th July.

“Bearing in mind your desire that I should confer with the Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba, I called upon Mr. Archibald, and learned from him that the Indians were anxiously awaiting my arrival, and were much excited on the subject of their lands being occupied without attention being first given to their claims for compensation.

“The first meeting, to which were asked the Indians of the Province and certain others on the eastern side, was to be held on the 25th of July, at the Stone Fort, a Hudson’s Bay Company’s Post, situated on the Red River, about twenty miles northward of Fort Garry—a locality chosen as being the most central for those invited.

“On Monday, the 24th of July, I met the Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba at the Stone Fort; but negotiations were unavoidably delayed, owing to the fact that only one band of Indians had arrived, and that until all were on the spot those present declined to discuss the subject of a treaty, except in an informal manner. Amongst these, as amongst other Indians with whom I have come in contact, there exists great jealousy of one another, in all matters relating to their communications with the officials of Her Majesty; and in order to facilitate the object in view, it was most desirable that suspicion and jealousy of all kinds should be allayed.

“It was thought necessary by the Lieutenant-Governor that Major Irvine, commanding the troops at Fort Garry, should be requested to furnish a guard at the Stone Fort during the negotiations, and that there should be at hand, also, a force of constabulary, for the purpose of preventing the introduction of liquor amongst the Indian encampments.

“Every band had its spokesman, in addition to its Chief, and each seemed to vie with another in the dimensions of their requirements. . . It was not until the 3rd of August, or nine days after the first meeting, that the basis of arrangement was arrived at, upon which is founded the treaty of that date. Then, and by means of mutual concessions, the following terms were agreed upon. For the cession of the country described in the treaty referred to, and comprising the Province of Manitoba, and certain country in the north-east thereof, every Indian was to receive a sum of three dollars a year in perpetuity, and a reserve was to be set apart for each band, of sufficient size to allow one hundred and sixty acres to each family of five persons, or in like proportion as the family might be greater or less than five. As each Indian settled down upon his share of the reserve, and commenced the cultivation of his land, he was to receive a plow and harrow. Each Chief was to receive a cow and a male and female of the smaller kinds of animals bred upon a farm. There was to be a bull for the general use of each reserve. In addition to this, each Chief was to receive a dress, a flag and a medal, as marks of distinction, and each Chief, with the exception of Bozawequare, the Chief of the Portage band, was to receive a buggy, or light spring wagon. Two councillors and two braves of each band were to receive a dress, somewhat inferior to that provided for the Chiefs, and the braves and councillors of the Portage band excepted, were to receive a buggy. Every Indian was to receive a gratuity of three dollars, which, though given as a payment for good behaviour, was to be understood to cover all dimensions for the past. On this basis the treaty was signed by myself and the several Chiefs, on behalf of themselves and their respective bands, on the 3rd of August, 1871, and on the following day the payment commenced.

“I take this opportunity of acknowledging the assistance afforded me in successfully completing the two treaties, to which I have referred, by His Honor the Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba, the Hon. James McKay, and the officers of the Hudson’s Bay Company. In a country where transport and all other business facilities are necessarily so scarce, the services rendered to the Government by the officers in charge of the several Hudson’s Bay Posts has been most opportune and valuable.

“WEMYSS M. SIMPSON,

“Indian Commissioner.”

Mr. W. F. Alloway, banker, Winnipeg, who came to Fort Garry from Montreal with the 2nd Quebec Battalion of the Wolseley Expedition in 1870 and was an eye-witness of this treaty, adds an interesting side-light to it:

“There seemed to be thousands of Indians present. Some time prior to the holding of the Treaty, an Indian by the name of Longbones had scalped his wife and for this he had been imprisoned in the penitentiary at the Lower Fort, but had escaped.

“At the Treaty it was whispered that Longbones was among the mob. The Indian Commissioner, Wemyss M. Simpson, demanded his surrender, which was refused. There then ensued a very long palaver (always dear to the hearts of the Indians), without results.

“At last Jim McKay (the Hon. James McKay), who was a splendid Indian linguist, was brought to the Lower Fort to harangue the Indians, which he did to such good purpose that Longbones was surrendered and the Treaty carried through.”

More Recent Times

In 1877 a serious accident occurred at Lower Fort Garry. A servant of the Company of the name of George Turner, for the purpose of celebrating Queen Victoria’s birthday on the 24th of May, obtained a barrel of black powder from the magazine and moved it to the blacksmith’s forge, which was situated outside the fort, to the south. While Turner was setting off amateur rockets to the delight of numerous spectators, including the children of the fort, the powder in the barrel in some way became ignited. An explosion followed which killed and injured a number of adults and children. This accident naturally cast a gloom over the fort for some time.

The creek, now dry, to the south of Lower Fort Garry was, in early days, the scene of great activity. It was one of the landing places of the brigades of York boats which generally came in from Edmonton, Swan River district, Lac la Pluie (Rainy river) and other places, about the middle of every June, bringing furs and returning with supplies.

Each brigade consisted of five or six boats; they were manned by halfbreed servants in charge of a guide (also halfbreed). A clerk in the Company’s service accompanied every brigade to ensure the safe carriage of the furs. Birch-bark canoes were at that time used only for “hurry-up” trips.

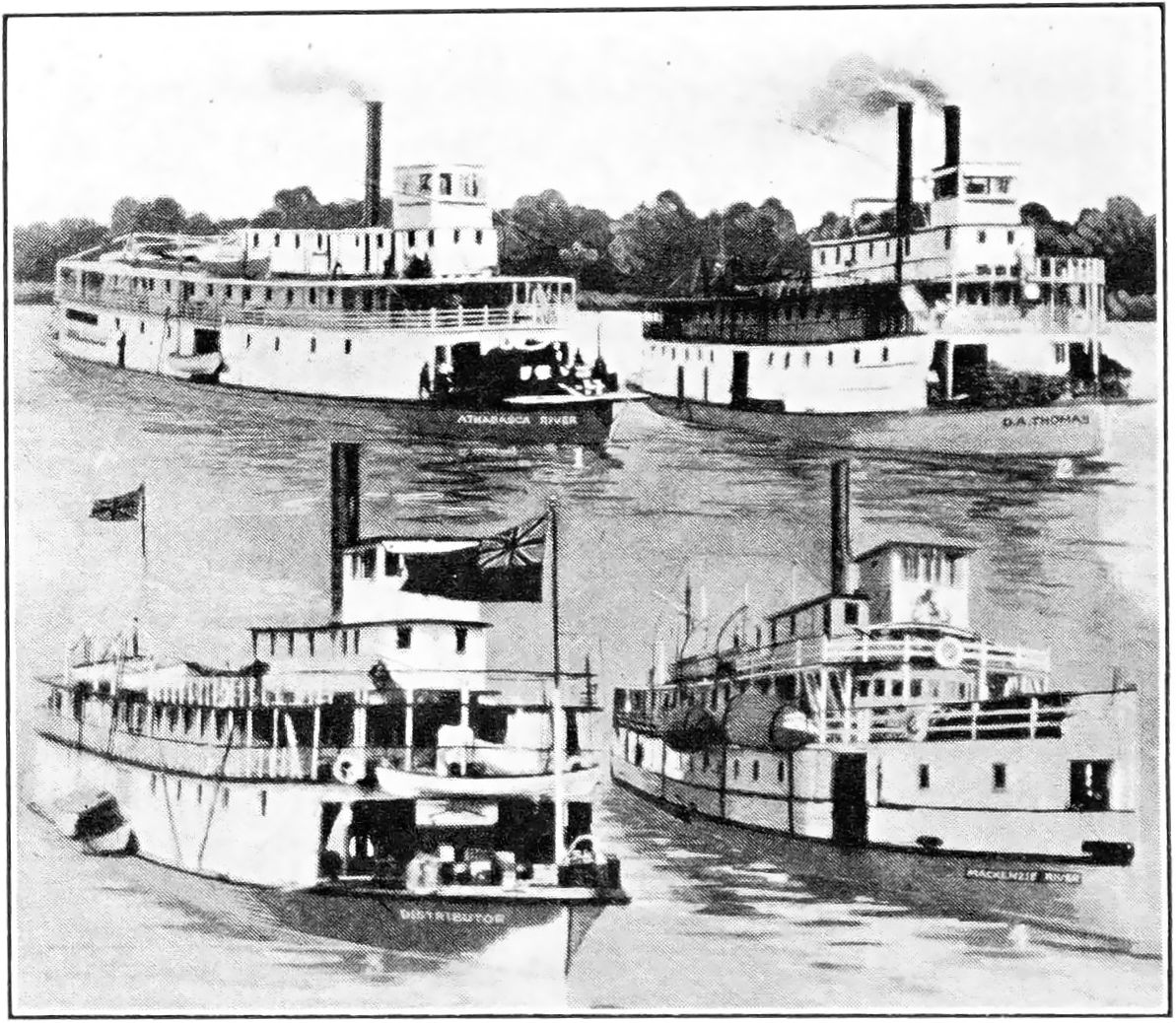

The creek was the landing place for the Company’s steamers, of which the schooners Polly (demolished and burned in 1887) and Colville were best known.

Sheriff Inkster remembers another boat, which was built at the Lower Fort in 1874, so that probably Lower Fort Garry was one of the first real shipbuilding yards in Western Canada.

This particular boat was christened by Mary Flett, daughter of the officer then in charge of the Lower Fort, who broke a bottle of champagne across her bow, saying, “God speed the Chief Commissioner”; but the Chief Commissioner refused to speed. She had been built for the shallow waters of the Little Saskatchewan, now known as the Dauphin river, and drew so little water that she was in continual danger of turning turtle.

Limestone is very noticeable along the beach by the creek, and Lower Fort Garry was built upon a great limestone bed. A quantity of heavy stones still strew the beach. These were brought down from Norway House as ballast by the steamer Polly when she was light in cargo.

Of the old buildings south of the fort, the men’s house and canteen, the blacksmith’s shop, the farm manager’s house, the grain flailing building, the root house, beer cellar, engineer’s cottage, store, malt kiln, grist mill, brewer’s dwelling and distillery, sawmill, miller’s dwelling and lime kilns, only the engineer’s cottage remains intact. This was occupied for a number of years by E. Abell, the engineer and boiler inspector of the Hudson’s Bay Company at the Lower Fort.

The flailing building was pulled down in 1911. The other buildings were removed or razed shortly after 1882, when the head of navigation for the Red river was removed to Old Colville landing, near Selkirk, on the east side of the river, to connect more directly with the branch railway line then being built by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, from East Selkirk into Old Colville for the Company’s trade.

250th Anniversary Celebrations

May 2, 1920, saw a return of the old Red River days to Lower Fort Garry for a brief period, when the “Adventurers of England” celebrated their 250th anniversary and the Indians in all their feathers, beads and gaudy habiliments came down the Red river in birch-bark and war canoes, foregathering from all parts of Canada—the prairies, Hudson Bay, the Arctic and the Pacific—to pay their respects and to renew, by smoking the pipe of peace with the then Governor, Sir Robert M. Kindersley, G.B.E., their pledge of friendship with the Company.

The Stone Fort has been preserved intact by the Hudson’s Bay Company, a worthy relic of the old Red River days.

Much water has flowed past the fort since its erection began in 1831, and the Canadian West has undergone a great transformation since then, but the old spirit survives. The men of today are the pioneers of the generations yet unborn, just as those sturdy fur traders were in the yester years.

Lower Fort Garry stands today, as it did almost a century ago, “four-square” with its surroundings. The old “sound of revelry” is gone, the song of the voyageur, the yap and snarling of the sled-dogs, the guttural of the Indian are no longer to be heard about its walls; in the mouths of the cannon and in the loopholes in the bastions the birds make their nests; the old sundial records the fleeting hours; the Red river flows on, and from the flagstaff the Union Jack floats buoyantly on the breeze over the peaceful scene, just as it has done for over two and a half centuries in every known part of this vast land.

Points of Interest

Numbers correspond with those shown on the plan of Lower Fort Garry.

Inside The Fort

-

Present entrance to Lower Fort Garry, formerly back entrance.

-

Originally men’s house, soldiers’ canteen in 1870. Later womens’ asylum (stone). Now a stable. Some of the original compartments remain intact.

-

Northwest bastion—The northwest bastion was the Company’s bake-house, for the baking of “hardtack” for the northern trade. It is now used as an ice house; the door is of recent manufacture. The land situated inside the west wall has been used as a garden for over twenty years. In the earlier days it was a wood yard.

-

North gateway.

-

Wooden house, used by Dr. Young, the prison doctor. Built in 1885. Now used as a laundry.

-

Prisoners’ yard. Formerly enclosed by high stockade.

-

Penitentiary and asylum. See page 43 for full description.

-

The remains of the oven built by the prisoners for the purpose of baking their own bread.

-

Small gateway between bastion and stockade which led to prisoners’ outhouse. Later built up.

-

Northeast bastion. This has always been used as a powder magazine.

-

Old storehouse (frame building). This building lodged the soldiers of the Wolseley Expedition of 1870 for a time. It was moved in 1881 to Old Colville landing, a few miles below Selkirk, where it became a warehouse for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

-

Guard room and sergeants’ mess, built 1870 for soldiers of Wolseley Expedition; now demolished.

-

and 14. East gate pillars. On the pillars of the east gate are the names of some of the soldiers who were stationed at Lower Fort Garry at the time of the Riel Rebellion in 1870, carved by the men themselves. The following names are still discernible :

North pillar (13)—Peter Cleland, R. Dunn, R. McGinn, — Bleasdale, B. Griffith, — Dean, S. Kealy, G. Connor, R. O’Neil, B. Browne, W. Curtin (June 15, 1872), — Gaunerau, D. F. Riley, John Marshall, B. Williams.

South pillar (14)—D. Forbes, — Thomas, A. Holliwell, — Swift, J. S. Kelly, D. J. Cowan, Cpl. E. Griffith (Apl. 25, 1871), Corp. Swanston, — Hill, J. N. Cornell, J. Naylor, J. Ryan, R. McGinn, J. D. Machon.

Bugler Joseph F. Tennant’s book, “Rough Times, 1870-1920,” contains the majority of these names in a list of the soldiers of the Wolseley Expedition to the Red River in 1870.

-

The stone deep in the ground in the centre of this gateway was placed there in 1883 by Alfred Franks and John Clouston. John Clouston was the stonemason who built the walls of the fort with Duncan McRae. The wooden gates at this entrance are of recent date, probably 1896. The trees inside the walls of the fort were never planted, but grew there, under the walls’ protection, from blown seed. They are about 30 years old.

-

Southeast bastion. This bastion was always used as an ice house. The door is said to be 92 years old. The old English lock is still on the door. Old English, hand-made nails are noticeable in the wood.

-

Position of old tethering posts. To the west of the south bastion, near the wall, were posts for tethering horses, from 1852 to 1911. The wall 30 feet from the end of the southeast bastion for 26 feet was pulled down to remove two houses intact in 1882. The wall was rebuilt immediately thereafter.

-

The part of the south wall which Riel, Lepine and O’ Donohue, with their followers, clambered over at midnight when they came to the fort in search of Dr. Schultz in 1870.

-

The Hudson’s Bay Company second retail store and fur loft. Still intact. Abandoned 1874. The foundations behind this are those of a small outhouse.

-

Foundations of another store (log and frame building). Built 1874; removed 1882.

-

Old site of the Lower Fort Garry bell.

-

Foundations of meat warehouse. Removed 1882.

-

Flagstaff. The old position of the flagstaff was to the south-east (31) inside the grounds of the Lower Fort, placed there so as to be prominent to river transport. This flagstaff, however, was blown down in a storm during Chief Trader (Big Bear) McLean’s regime, 1886 or 1887 and was then set up on its present site. It is merely wedged with block stones and braced. At the time of its re-erection a bottle containing coins, also the names of Mr. and Mrs. McLean’s family who were taken prisoners by the Indians during the rebellion of 1885, was buried alongside the base of the pole.

-

Southwest bastion. The entrance to this bastion has a very old door and lock. These seem to be the originals. This bastion was first used as a washhouse and cookhouse for the first soldiers located in the fort about 1846, long before the first Riel Rebellion. Later it was used as a storehouse.

-

Foundations of an old stable.

-