Signes gravés sur les églises de l'Eure et du Calvados

Signes gravés sur les églises de l’Eure et du Calvados

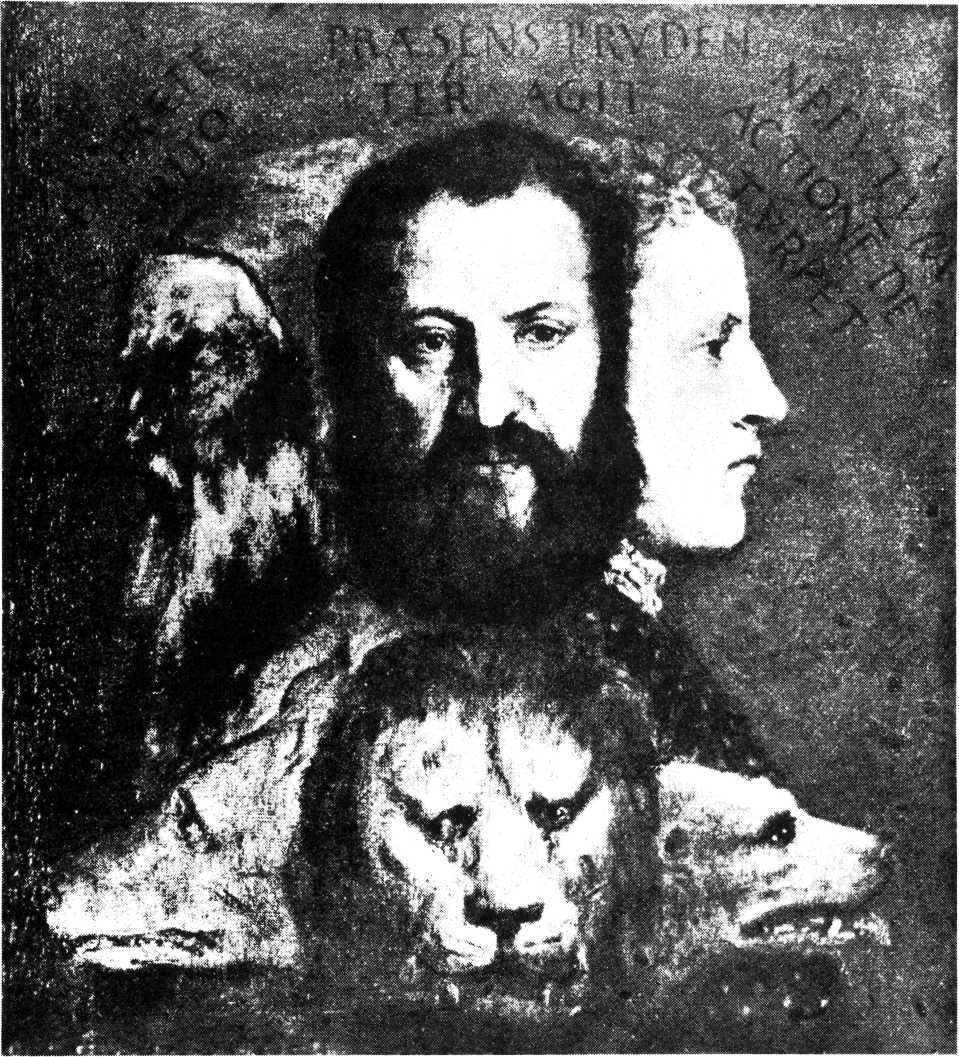

»Jusqu’à maintenant, les positions des problèmes philosophiques n’ont jamais été dans l’Histoire aussi éloignées, aussi complètement indifférentes les unes des autres, ainsi qu’aujourd’ hui entre la philosophie dans le monde Anglo-Saxon, la Scandinavie inclue et la philosophie du continent.«

Cette observation de K. E. Løgstrup se voit accentuée sur des plans multiples depuis la prise de vue des photographies qui composent ce livre, et le projet des textes qui s’y rapportent.

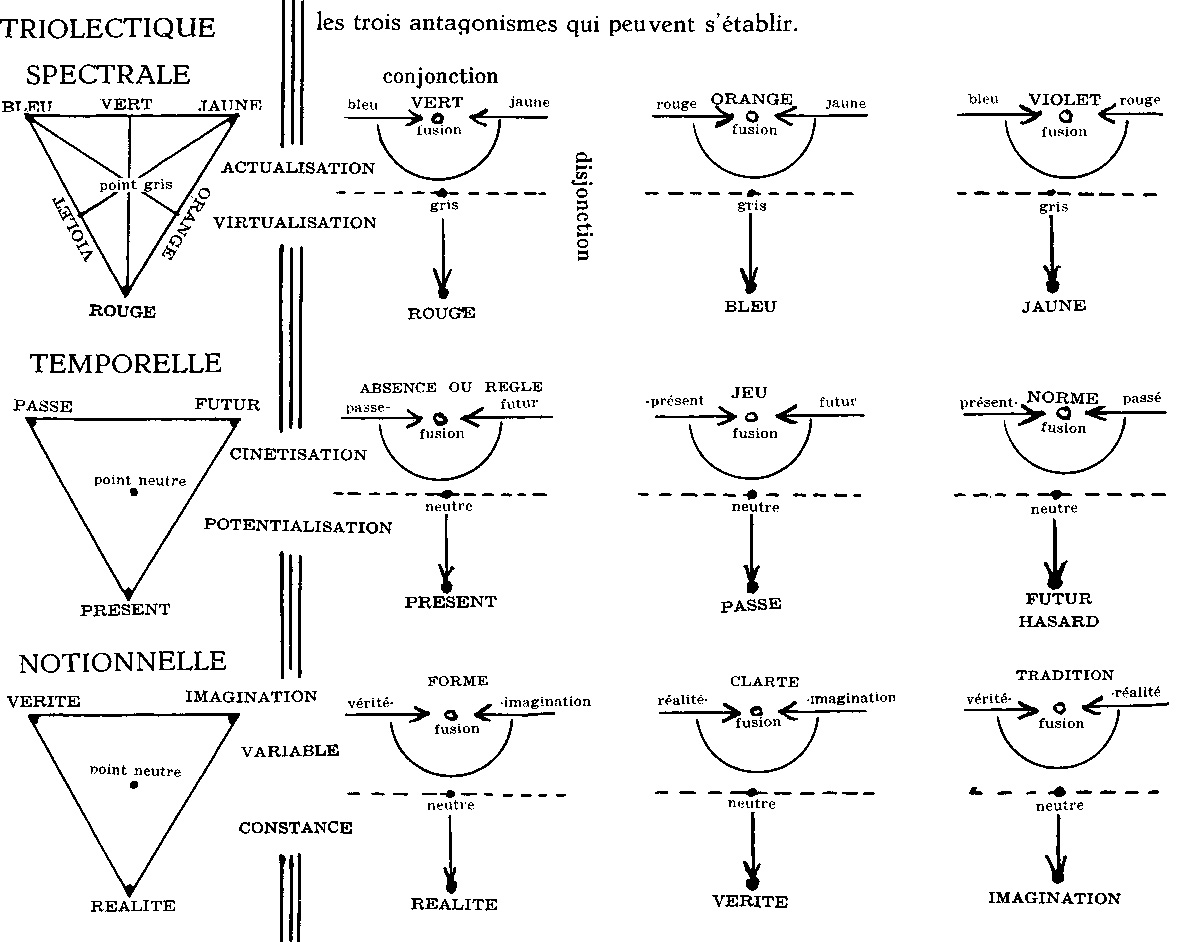

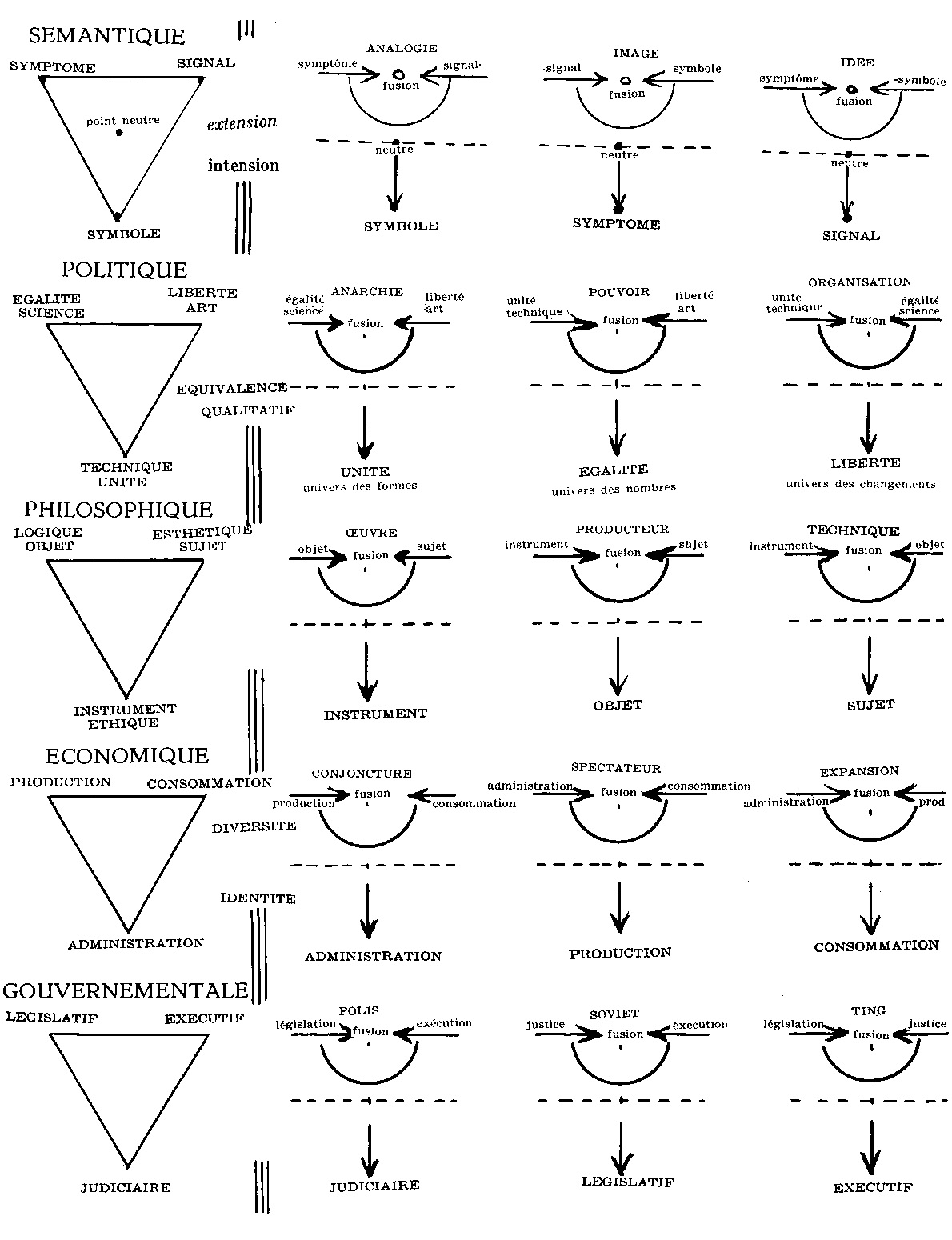

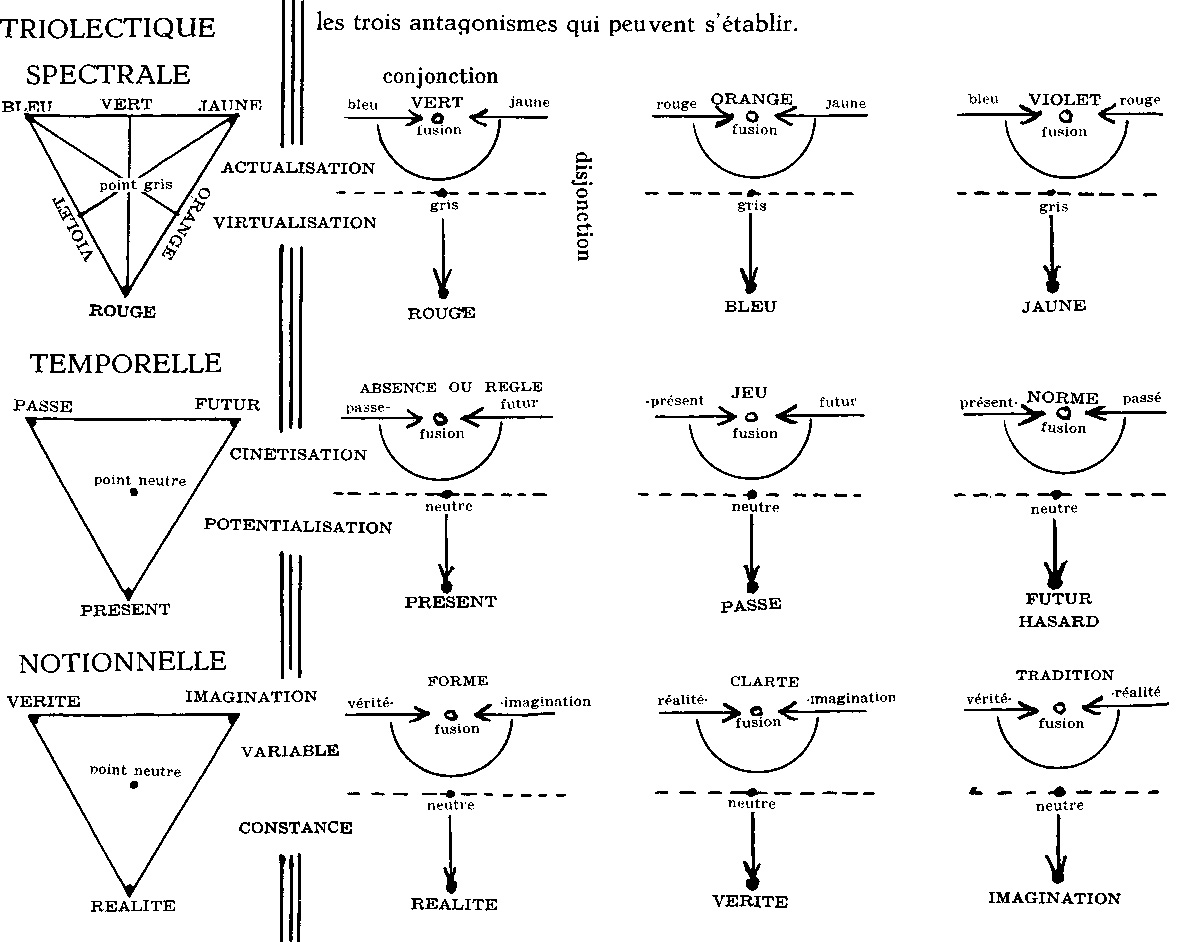

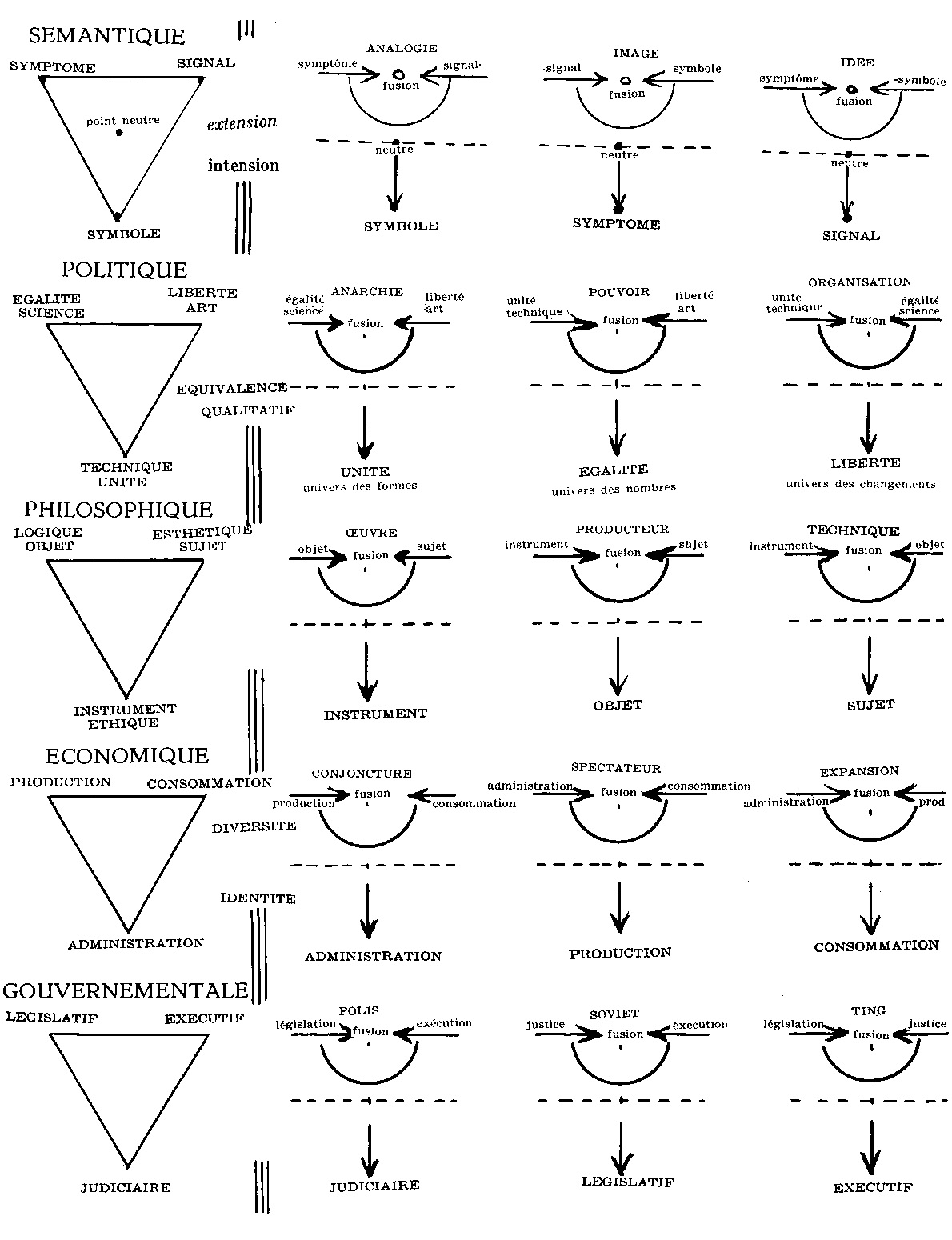

Ainsi Asger Jorn s’est senti dans l’obligation de modifier son étude. Il a ajouté son schéma TRIOLECTIQUE, qui démontre le mécanisme de cette COMPLEMENTARITE DE PENSEE, en ésperant une possibilité de conciliation par cette nouvelle méthode.

Les textes de P. V. Glob et G. Gjes- sing représentent l’étude nordique dans le domaine des grafittis, sans aucun rapport avec le problem ici exposé.

ÉDITIONS BORGEN

INSTITUT SCANDINAVE DE VANDALISME COMPARÉ

SOUS LA DIRECTION D’ASGER JORN

Cet ouvrage constitue le deuxième volume de la Bibliothèque d’Alexandrie, édité par l’Institut Scandinave de Vandalisme Comparé. Le premier volume de la Bibliothèque d’Alexandrie est le recueil des cinq monographies de cette collection consacrée, entre 1959 et 1964, à Constant ( urbanisme unitaire situationniste), Pinot- Gallizio (peinture industrielle), Jorn et Wemaëre (tapisserie spontanée), Guy Debord (réalisations cinématographiques), et aux Origines de l’Internationale situationniste .

Secrétariat de l’Institut Scandinave de Vandalisme Comparé: Hans Kjaerholm, Banegaardspladsen, 4, Aarhus, Danemark.

BIBLIOTHÈQUE D’ALEXANDRIE — VOL. 2

SIGNES GRAVÉS SUR LES ÉGLISES DE L’EURE ET DU CALVADOS

ÉDITIONS BORGEN

LES PHOTOGRAPHIES DE CET OUVRAGE ONT ÉTÉ RÉALISÉES PAR GÉRARD FRANCESCHI

TEXTES:

INTRODUCTION, par Asger Jorn.

RELEVÉ DES SITES DU CALVADOS ET DE L’EURE.

SIGNES DU CULTE DE LA FÉCONDITÉ, par P.-V. Glob, Archiviste National du Danemark, Directeur du Nationalmuseet de Copenhague.

NORD ET NORMANDIE, par Gutorm Gjessing, Professeur d’Ethnologie à l’Université d’Oslo.

UNE LETTRE, de Michel de Bouard, Doyen de la Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines de l’Université de Caen.

LE VANDALISME IMBÉCILE: LA GRAFFITOMANIE, par Louis Réau, extrait de « L’Histoire du Vandalisme » ( « Les Monuments détruits de l’Art français», 1959).

SAUVAGERIE, BARBARIE ET CIVILISATION, par Asger Jorn, traduction de Jean-Jacques Rock.

« On a tout volé au peuple. » Jacques Prévert.

« … Et même sa possibilité créatrice. » Asger Jorn.

INTRODUCTION

Lors d’une visite que je fis à l’église de Damville, en Normandie, en 1946, et pendant mon séjour chez le peintre Pierre Wemaëre, à Pinson, mon attention fut attirée par les grattages et graffitis dont le porche de cette église était abon~ damment recouvert.

Remarquant plus tard de semblables grattages au Danemark, en Suède et en Norvège, sur les cathédrales de Ribe, de Lund et de Trondhjem, je décidai d’étudier ce phénomène de plus près.

Les moyens nécessaires à cette entreprise me furent donnés au printemps 61. Je partis alors pour l’aventure normande accompagné du photographe Gérard Franceschi.

Nous trouvâmes dans les départements de l’Eure et du Calvados un nombre de graffitis important. En d’autres zones on ne trouve rien. Partout où les églises ont été restaurées, les traces de graffitti ont disparues. Quelquefois, comme l’exemple n° 178, une partie se dévoile quand un morceau de stuc superposé est tombé.

De nombreuses inscriptions, tant en latin qu’en français, présentent un grand intérêt historique, nous les avons cependant ignorées.

Nous n’avons trouvé aucune image, ni d’accouplement, ni de coeurs percés d’une flèche. Les reproductions présentent avec fidélité tous les sujets trouvés. Il n’y a ainsi pas. de possibilité d’un choix de sujets adaptés à une interprétation, préétablie. L’unique grafflto qui a été retracé fut l’empreinte des pieds n° 73.

Au commencement, les recherches se faisaient un peu par hasard, ce qui explique le manque d’indication d’origine de quelques-uns. Mais toutes les églises visitées sont dans le registre et un surcroît de précision exigerait un second parcours pour lequel je n’ai pas le temps nécessaire.

A aucun moment, je n’avais supposé que nous pourrions véritablement faire une très riche récolte d’images. Et non plus que les signes, seraient admirablement conservés. Ce fut pourtant le cas.

Les ouvrages et études sur des thèmes semblables m’ayant paru être d’une grande pauvreté, je fus tenté de réunir les magnifiques photos de Franceschi et les textes de quelques-uns des meilleurs spécialistes en ce domaine.

Je m’empresse de dire que ces derniers qui manifestèrent pour mon projet un intérêt dont je les remercie vivement, ont confondu, par la gentillesse et la chaleur de leur accueil, l’amateur que je suis.

ASGER JORN.

SIGNES DU CULTE DE LA FÉCONDITÉ

P. V. GLOB,

Archéologue

Tout un univers d’images d’un caractère particulier a traversé tranquillement le temps, sur les murs des églises de Normandie. Et pourtant il était soumis à un développement et un enrichissement perpétuels. Il a été évoqué par un artiste au regard alerte, qui nous le communique maintenant. Ces étranges signes et images, exécutés et connus par la population locale seulement, sont ainsi dans ces pages exposés à l’attention d’un public plus vaste, dans d’autres pays.

Une abondance de signes et de symboles s’étale sur ces surfaces de pierre, et justement parce que ces dessins ne sont pas dûs à une seule main d’une époque précise, mais représentent l’activité d’une multitude, depuis des époques reculées jusqu’à nos jours, chaque surface se fond dans une unité très vivante, à laquelle participe aussi la nature par ses jeux de couleurs avec le gris-brun-jaune des fleurs du lichen.

Il est impossible de dater les premières images. Même en datant, avec une relative précision, les nombreuses églises, les châteaux et les fermes, où l’on peut trouver les pierres imagées, il n’en reste pas moins que pour certaines d’entre elles, la place qu’elles occupent actuellement peut ne constituer que leur deuxième usage, leur origine se trouvant dans des lieux cultuels vieux de plusieurs millénaires. De telles pratiques sont bien connues. Ceci concerne principalement les pierres comportant des creux en forme de coupe, tels qu’ils sont disposés sur les premières pages: librement semés, ou bien en lignes droites, cercles, rectangles et autres formes géométriques qui peuvent figurer des hommes aussi bien que des animaux. Ce symbole est connu du monde entier, dans sa plus haute antiquité. On peut le suivre jusqu’à cinq mille ans dans le passé, dans cette même matière et ce même caractère que nous retrouvons ici. Ces trous creusés dans la roche sont aujourd’hui encore l’objet de pratiques culturelles au pied de l’Himalaya, où les femmes y apportent leur offrande de calices de fleurs jaunes pour s’assurer, au moyen de ce symbole du sexe féminin, la fertilité et le bonheur.

Les creux cupuliformes semblent suivre l’ancienne voie de communication culturelle qui se continue depuis le Moyen-Orient, à travers la Méditerranée et le long des côtes de l’ouest européen, jusqu’aux pays nordiques attachés à un culte de fertilité particulier. Ce culte avait réussi à se soumettre ce domaine immense, à partir du troisième millénaire avant notre ère, et jusqu’à la fin du premier millénaire de celle-ci.

Dans l’ouest de la France, ce signe est attaché, entre autres, aux magnifiques tombes de pierres du golfe du Morbihan en Bretagne, qui sont du deuxième millénaire. On le trouve aussi sur la pierre des menhirs formant d’immenses chemins de procession, tels par exemple les alignements de Kermario Plusieurs de pierres ici reproduites pourraient être prises dans des lieux semblables; de même que 1 on trouve souvent au Danemark d’anciennes pierres — avec les creux cupuliformes — réemployées dans le bâti des seuils, ou comme socles (voir le numéro 6).

Nous ne savons pas jusqu’à quelle époque ce signe a gardé sa puissance magique, mais on le retrouve aussi, reproduit en grand nombre d’exemplaires, sur les pierres des perrons du fameux temple d’Athéna, sur l’acropole d’Athènes, tracé longtemps après que le temple fût achevé. De nos jours, on le voit servir à des jeux, tout autour du Golfe Persique, et aussi en d’autres endroits. Ceci n’empêche pas qu’il ait pu contenir pour les gens de ces régions d’autres significations plus anciennes; mais implique au contraire un problème du rôle rituel que les anciens jeux ont pu tenir, en matière de divination.

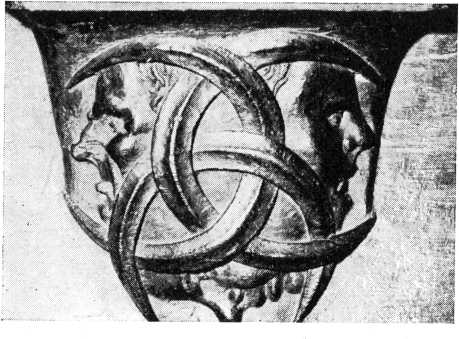

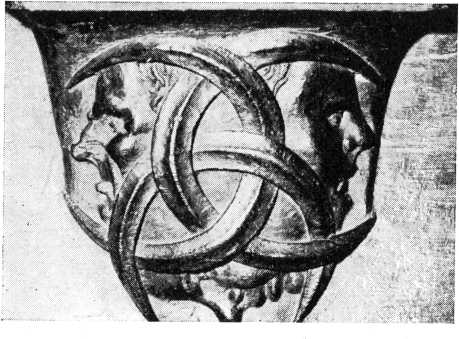

Les creux en forme de coupe sont, dans l’ensemble de la zone méditerranéenne, ouest-européenne et nord-européenne, rattachés au vieux culte de la Terre-mère. Une longue série de signes: cercles autour de trous, une roue avec croix, creux et cercles prolongés de rayonnements, etc. (numéros de 16 à 30), se trouve cependant axée sur les forces du ciel, culte qui pénètre avec des peuples à cheval qui envahirent le Nord et l’Europe Centrale, il y a environ 4.000 ans. A partir de cette époque, et dans les quelques millénaires qui suivent, ces deux religions, celle du ciel et celle de la terre, se rencontrent et se réfractent dans l’art des images, et lui donnent son contenu. Nous trouvons cet art sur les monuments mégalithiques, tant dans le golfe du Morbihan qu’en Irlande de l’Est, où nous pouvons rencontrer tous les creux, les cercles et les autres signes qui sont dans ce livre. Quand bien même le signe circulaire, dans ses nombreuses variantes, apparaît lié à la puissance solaire, il n’en est pas moins probable qu’il convient de le considérer, dans certains cas, comme l’œil qui veille sur la déesse-mère.

Le même rapport avec un culte de la fertilité qui s’est maintenu jusqu’à nos jours se reflète aussi dans beaucoup d’autres images de ce livre. C’est le cas de nombreuses empreintes de pieds, simples ou doubles, qui se combinent souvent, dans l’ouest et le nord de l’Europe, avec les creux en coupe. Ce signe, en même temps que celui du soleil, peut être suivi à travers tout l’âge de fer, jusque dans la période chrétienne (numéros 68 et 74). Les nombreuses empreintes de pieds sacrés sur les roches et les pierres de l’Inde sont attribués à Bouddha ou à Vishnu, mais dans beaucoup de lieux existent de vieilles traditions qui attribuent à l’empreinte du pied humain une puissance bénéfique, fertilisante, productive. Il s’agit du même cas avec le soulier, connu ainsi dans la culture grecque, entre autres. Cette tradition se survit jusqu’à notre époque, dans l’habitude d’attacher un soulier à la voiture des mariés. On voit ainsi des empreintes de soulier avec indication du talon (numéro 73) et le soulier lui-même (numéro 75). Le type de ce soulier appartient aux XVIe-XVIIe siècles, ce qui indique la date de son exécution. En général, le pied en tant que symbole de puissance aussi bien que la main (numéros 78 à 82), protège contre les forces maléfiques et acquiert, à travers des rites magiques, une puissance divine qui se répand à l’endroit où il a été dessiné.

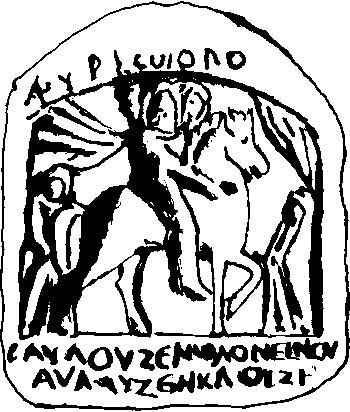

Le cheval, cet animal merveilleux, appartient aux puissances du ciel. Il arrive des steppes de l’Asie à la fin du troisième millénaire avant J.-C., comme bête de trait, comme monture, et comme animal laitier. Son image est puissante, et provoque la fertilité (numéros 107 à 112). Il tire le soleil derrière lui à travers le ciel, il est lié au feu. Ainsi était attaché au dieu de la fertilité, dans le paganisme nordique, un trait qui se manifeste jusqu’à nous avec la corvette en forme de cheval, dans les environs de Lille. Aussi bien l’image du cerf (numéros 95 à 102) et celle de l’oiseau (numéros 61 à 66) se placent-elles dans cette même catégorie.

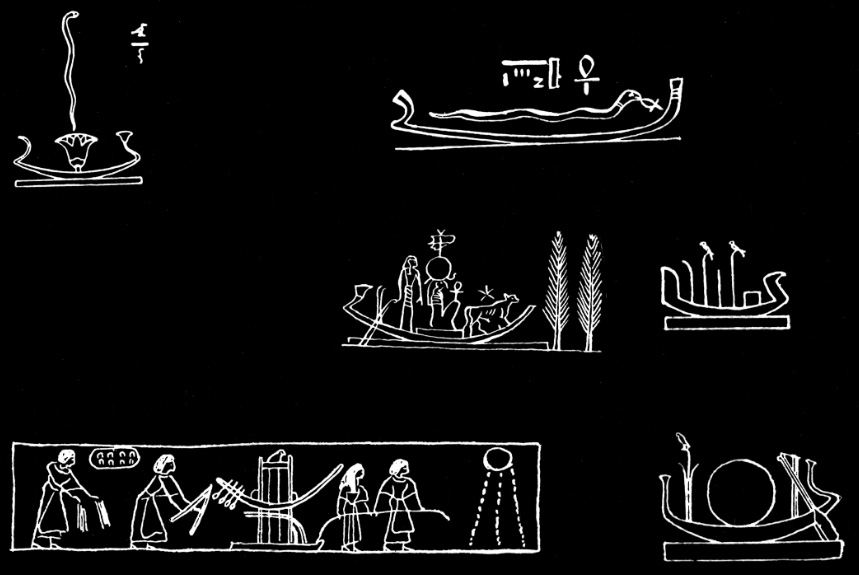

Il y a une série de bateaux toutes voiles dehors, dont quelques-uns pourraient être faits par nos grands-parents (numéros 40 à 48), et d’autres plus anciens. Tous rappellent la nef de l’église et le bateau du carnaval. Le bateau lui-même appartenait, il y a trois mille ans, au dieu de la fertilité dans le Moyen-Orient, en Grèce (le bateau de Dyonysos), et dans le Nord où les rites de fertilité étaient inséparables de défilés populaires avec des bateaux. Ce transport de bateaux est encore connu actuellement, notamment dans les défilés de carnaval, même si son but original est oublié. En Normandie, il semble pourtant que des souvenirs de l’antiquité aient été gardés au fond des esprits.

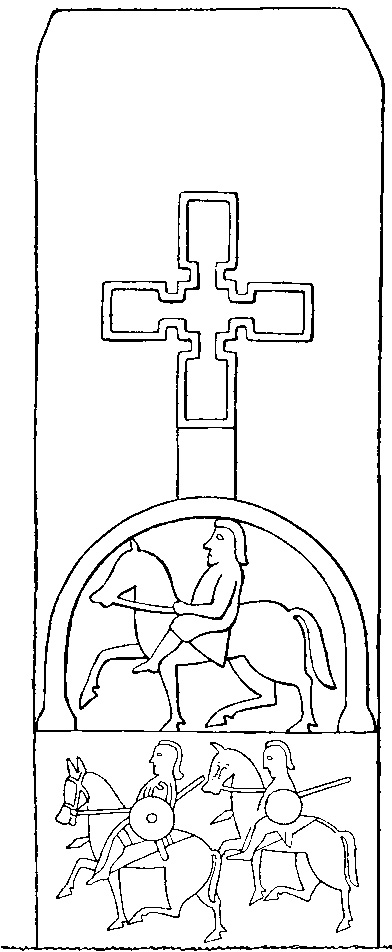

Plusieurs sujets confirment la coexistence de ces images avec la culture chrétienne officielle. Les cathédrales superbes et les modestes lieux de prière (numéros 158, 62), les cloches des églises (numéro 176), la pierre tombale (numéro 137), les clés de Saint-Pierre (numéro 83) et l’échelle du ciel (numéro 116). La clé était, à l’époque viking, il y a mille ans, le signe porté au cou, en argent ou en bronze, comme témoignage d’attachement à la croyance chrétienne; cependant que d’autres portaient le signe du marteau pour manifester leur fidélité envers les anciennes puissances du ciel (il est difficile de savoir s’il faut interpréter ainsi les numéros 194-196). Même si le christianisme régnait apparemment à la surface du pays, il s’avère que des croyances bien plus anciennes dominent le monde d’images ici relevé. Ceci n’est pas un cas unique, et tous ceux qui visitent le charmant Frascati, à Monti Albani, au sud de Rome, peuvent encore aujourd’hui croquer d’une dent affectueuse les figurines des femmes à trois seins qui sont vendues dans les petites boutiques des boulangers, témoignage présent de l’ancienne déesse de la fertilité: Astarté, Aphrodite ou Ava, ou quelque autre nom qui s’est donné à la Magna Mater, la mère des origines.

NORD ET NORMANDIE

Gutorm GJESSING,

Professeur d’Ethnologie à l’Université d’Oslo.

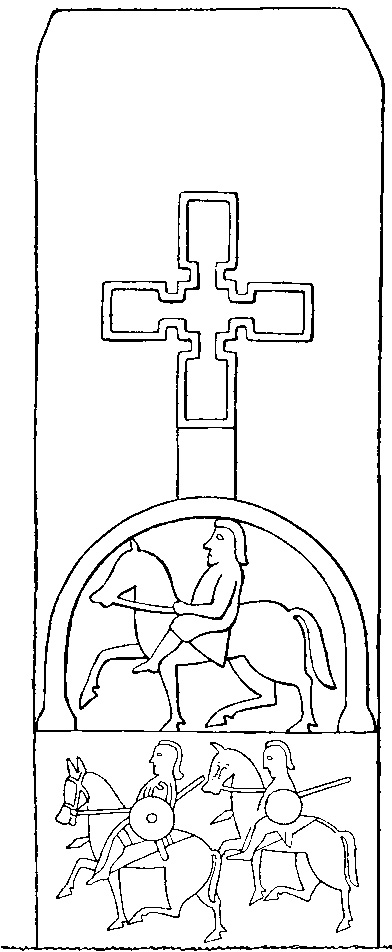

Les images de ce livre sont choisies entre des milliers de signes gravés ou dessinés sur les murs des églises, en Normandie. Il y a parmi eux des représentations d’églises et de clochers, mais avant tout une abondance de croix, généralement posées sur des bases de différentes formes. On rencontre même le coq qui représente la vaillance (numéros 64 et 67) ou des cœurs, parfois des cœurs entrelacés. La fleur de lys s’y trouve en quelques endroits, ou bien des motifs plus lugubres, comme la potence où pend le malfaiteur. En plus de cela, un grand nombre de sujets, apparemment sans intérêt particulier, appartiennent à la vie de tous les jours: des chevaux, souvent avec un cavalier, des cerfs, des oiseaux, des serpents, des empreintes de pieds, des mains, et une quantité incroyable de petits trous ronds en forme de coupe. Ces sujets ne sont pas, et de loin, aussi insignifiants qu’ils en ont l’air. Ils sont même plus intéressants que le reste.

Quelques-unes de ces figures sont datées. Un cerf est daté de 1753. Un peu plus haut, sur le même mur, on trouve le chiffre de 1780 — et quelque chose, le dernier chiffre étant effacé (numéro 99). A un autre endroit, il y a le chiffre 164; peut-être 1640. On trouve encore d’autres dates: 1602 (?), 1620, 1740, 180 (?), sans que ces dates correspondent directement avec les dessins. Une indication assez précise se trouve dans les différents styles, et surtout dans les différents types de bateaux. Cela nous prouve que les origines de ces dessins sont très diverses, à partir du Moyen Age et jusqu’à la fin du siècle dernier. Le bateau du numéro 59 semble être gravé aux environs de 1110, alors que des trois-mâts, des bateaux gréés en frégates, des goélettes, des bricks portant toute leur toile, quelquefois des sloops et même un caboteur avec un gréement en fourchette peuvent difficilement être antérieurs à l’époque qui entoure 1800. Un bateau à roue (l’apparition de la vapeur) confirme ceci. Et l’animal qui retourne la tête pour se mordre la queue appartient en revanche aux sujets classiques de l’art roman (numéro 114).

La superposition de plusieurs couches de figuration montre aussi, par le relevé chronologique de la facture des images qui devient ainsi possible, que de longues époques sont passées sur cette entreprise. Même avec des photographies d’une qualité remarquable, comme elles se présentent ici, il serait vain de tenter l’analyse des différentes couches chronologiques à partir de la reproduction photographique de l’ensemble. Il est d’autre part très improbable que l’établissement d’un tel relevé puisse nous apprendre quelque chose dont l’importance puisse être mise en balance avec l’immense somme de travail, et la longue durée, qui seraient impliquées par une recherche sur les monuments eux-mêmes.

Il ne s’agit pas ici d’un art professionnel, de quelque espèce que ce soit. C’est l’homme simple, plus ou moins pieux, qui passe son temps là en attendant le commencement de la messe; ou plus vraisemblablement, après avoir apporté ses offrandes, au Sauveur, à la Sainte-Vierge et aux autres saints. Les images ne sont guère réalisées en tant qu’œuvres d’art, au sens que nous donnons actuellement à ce terme, sauf dans quelques rares tentatives où l’on sent un désir esthétique conscient. Ceci se manifeste le plus clairement dans la rosette (numéro 173) où la tension entre le carré et les courbes de la rose à huit feuilles, jointe à la technique décidée, montre qu’il s’agit d’un artiste « populaire » ayant du métier et du nerf. D’autres figurations montrent le sentiment de la forme et la sûreté de la main, et atteignent à des résultats frappants. C’est le cas de plusieurs bateaux, tels le sloop numéro 46, le caboteur (yacht ?) numéro 48, ou le brick numéro 58. Souvent les cercles ont été exécutés avec des compas de diverses sortes. Ceci est surtout visible avec ceux où s’inscrivent des rosettes à six feuilles.

On peut pourtant constater, comme règle dominante, que la préoccupation essentielle est l’image, le symbole, ou plutôt la métaphore elle-même. C’est ainsi que cela participe de ce qu’on appelle Vart populaire, dans sa forme la plus authentique. Les gens les plus ordinaires ont ressenti le besoin de s’exprimer en images, d’y traduire des choses élémentaires et centrales dans la vie de leurs intérêts et de leurs sentiments; et avec cela, d’y mettre à jour des images associatives, qui ont surgi par un hasard apparent des profondeurs fermées de leur inconscient, et c’est justement cette dernière partie qui offre tant d’intérêt.

Parce que l’inconscient ne crée pas des associations dans le vide. Elles se réalisent sur la base des expériences prétendûment « oubliées », et ce qui constitue les traditions, ce sont précisément de telles expériences effacées. Pour être réellement capable de valoriser la signification de ces images, nous sommes obligés de faire une mise au point préalable, sur ce qui constitue la tradition dans son fondement ultime; et ensuite de préciser quelques données de l’ancienne histoire de Normandie, pour pouvoir situer les traditions présentées ici.

La tradition engloble tout ce qui se passe de génération en génération comme croyances, habitudes, idées et images. Elle n’est pas subjective dans le sens d’individuel, d’appartenance à des hommes particuliers. Elle est au contraire une accumulation englobante des expériences vécues dans la société entière, représentant ainsi une subjectivité commune à tous. Ceci ne caractérise pas seulement la petite société locale, mais aussi des unités ethniques plus vastes, le peuple ou la nation. Elle joue même dans ce que l’on peut appeler la grande cohésion de la culture sociale: ce qui est ordinairement nommé « notre civilisation occidentale », et ce qui est caractérisé par l’Américain Robert Redfiel du nom de « the great tradition ».

La tradition accumule les éléments de partout, et couvre des générations innombrables. Mais la tradition est loin d’être statique; elle est sans arrêt engagée dans un processus de transformation. De nouvelles expériences s’ajoutent sans cesse, alors que d’autres disparaissent.

L’intelligence consciente est toujours individuelle et analytique, parce que l’attention envers les choses est nécessairement auto-centrée. La conscience est comme un phare, qui peut envoyer partout son rayon d’éclairement, et ainsi couvrir l’horizon tout entier, mais seulement par petits secteurs, successivement. La tradition est au contraire synthétique, englobe tout, et prend par ce fait un caractère apparemment objectif, parce que tous les apports de l’expérience « oubliée » sont fondus dans une grande unité plastique, dont la cohérence est parfaite dans le temps aussi bien que dans l’espace.

Tout le processus de traditionalisation qui s’est fait depuis le commencement se poursuit aujourd’hui, et continue vers le futur. Ce qui est oublié ne disparaît pas. Cela s’enfonce seulement jusqu’aux niveaux du subconscient et de l’inconscient; et les événements d’hier sont déjà en route vers la masse traditionnelle. Ce processus s’est prolongé à travers un million d’années ou même plus, puisque la tradition semble être aussi un facteur partiellement constitutif du comportement animal.

La véritable tradition est inconsciente, parce que nous vivons dedans et sommes sans arrêt formés par elle. Une fois rendue consciente, elle change entièrement d’aspect, elle se transforme en traditionalisme, phénomène qui joue un rôle considérable, et très largement dangereux, dans le monde dynamique moderne, qui donne si peu de libre jeu aux vraies traditions, ni du même coup à l’imagination. Combiné avec le dynamisme expansif de notre époque, le traditionalisme moderne développe un désir de puissance nationale qui est étranger aux traditions authentiques.

Ce qui est le plus difficile à définir, ce sont les éléments traditionnels qui proviennent de cohésions d’une grande amplitude, ou qui se sont liés à une pareille cohésion, parce que dans leur cas tous les éléments de détail de ce grand ensemble sont à un point tel en interaction qu’ils changent de caractère au fur et à mesure; de la sorte, ils deviennent très difficiles à localiser dans le jeu de l’ensemble. Des traditions locales, au contraire, sont souvent assez faciles à montrer. Comme exemples de telles traditions purement locales, nous allons mentionner quelques cas dont l’incroyable antiquité a pu être établie par les archéologues. Ces exemples sont limités au seul domaine Scandinave, mais on pourrait sûrement en trouver de semblables dans beaucoup d’autres pays.

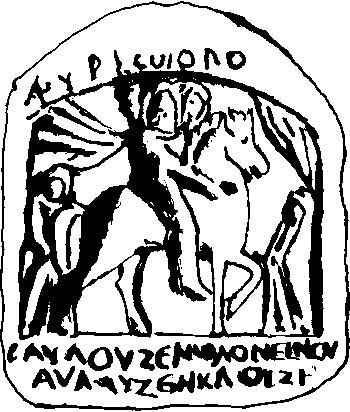

Ange féminin tournant la roue des corps célestes, à l’exté-térieur de la cathédrale de St. Vit. Hradcin, à Prague. Wenceslas de Budovica, 1490. D’après R. Eisler.

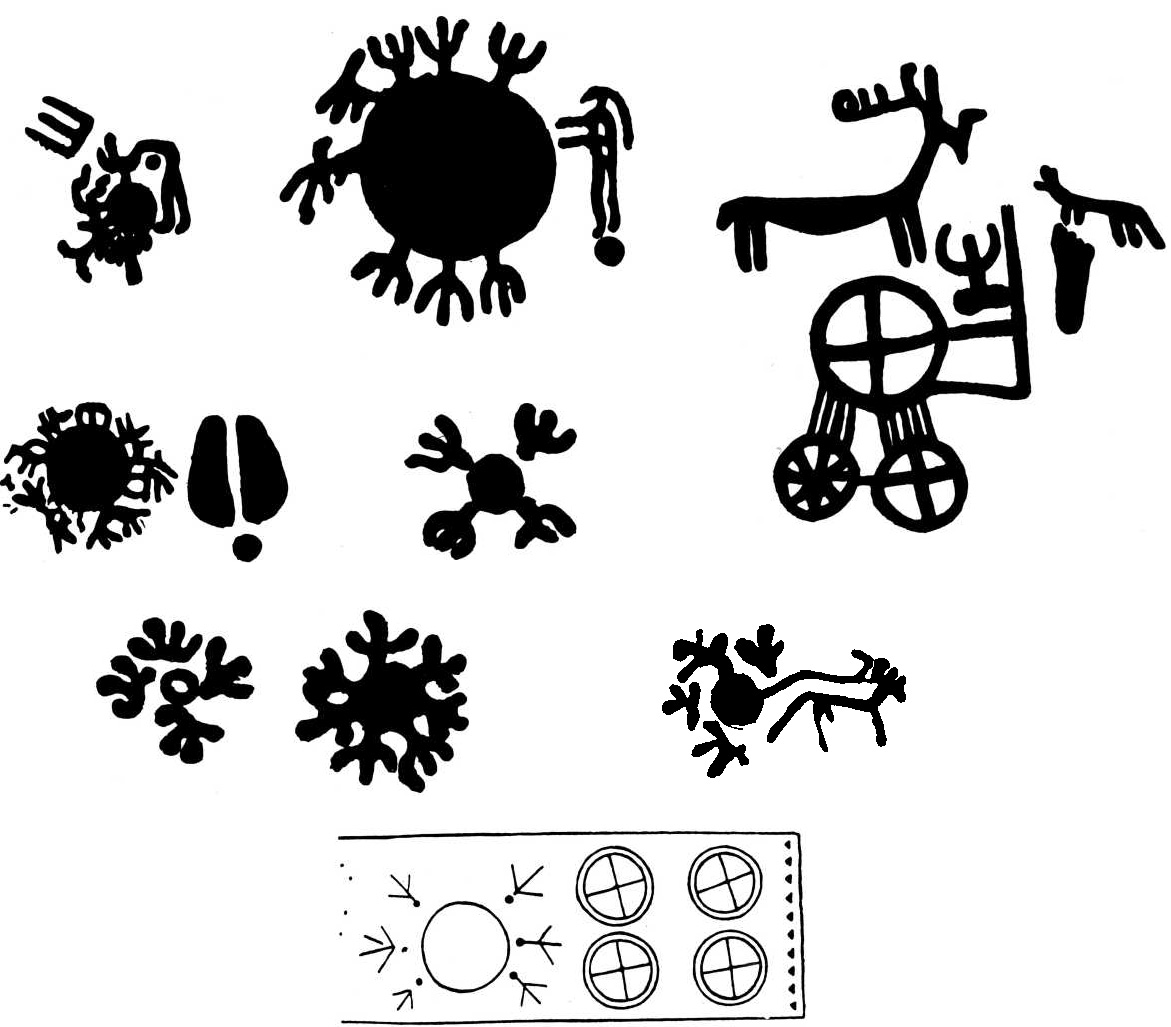

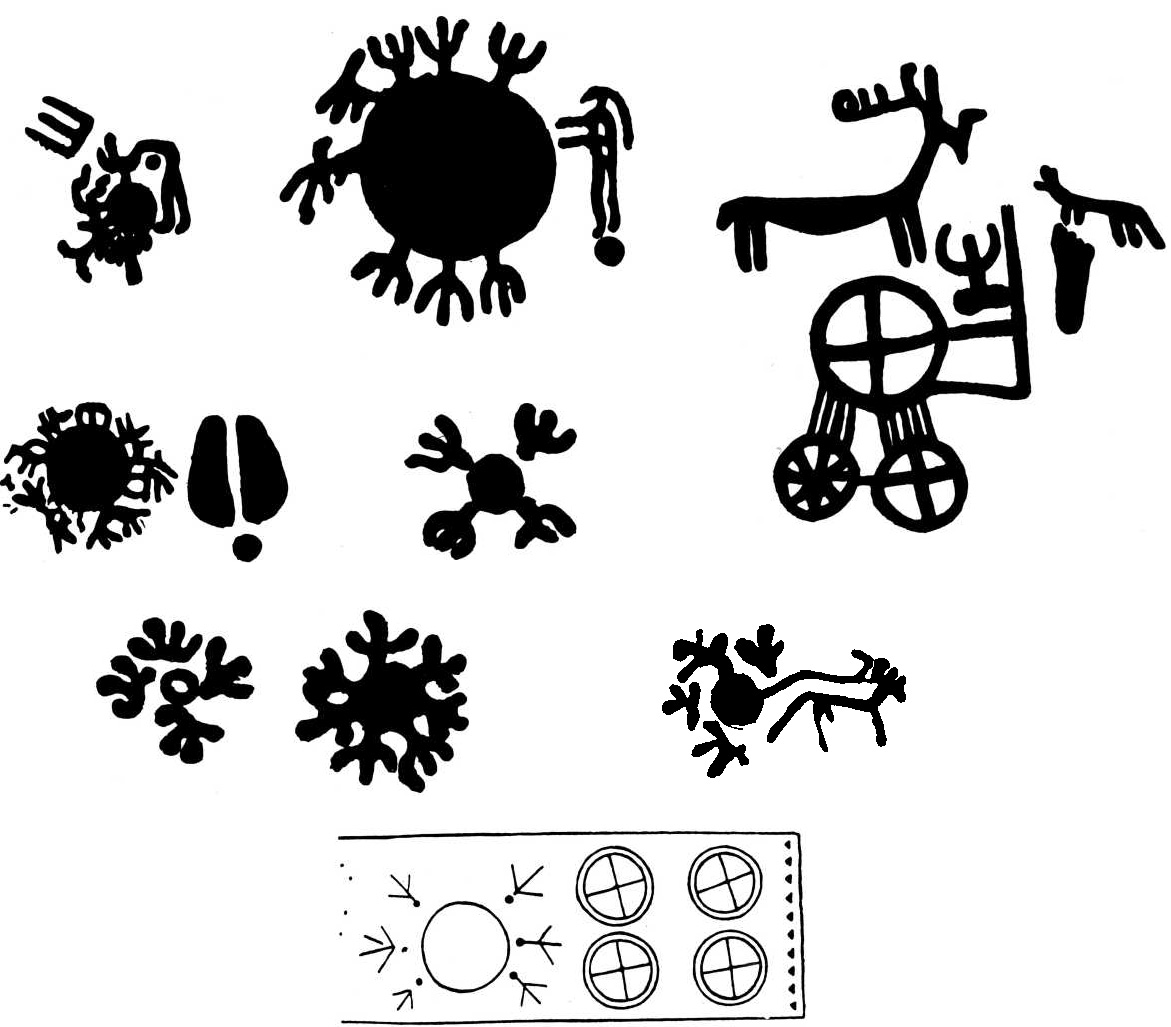

Gravures rupestres de l’âge de bronze (Suède) montrant le même sujet. Ici les empreintes des pieds et le creux cupuli~ forme signifient la déesse maternelle de la terre. Elle affronte le cerf céleste en bas. Ici l’on voit que la roue, dans l’antiquité, était le signe du zodiaque plus qu’une roue solaire.

L’archéologue Karl Rygh rapportait, de son temps, ceci: «En 1876 on m’avait expliqué, dans le pays de Strinda aux environs de Trondheim, qu’il y avait une légende selon laquelle un chevalier en armure et son cheval se trouvaient sous un grand rocher. Il y aurait été surpris par une chute de pierres alors qu’il passait dans la vallée, et écrasé. Je pris la peine de creuser sous le rocher aussi loin qu’il m’était possible, et je trouvai effectivement les ossements d’un cheval et d’un homme, et en plus un acier de briquet et deux pointes de lance datant manifestement de l’époque viking.. La présence d’une tombe était exclue ». Il faut avouer que le pauvre cavalier, après son enterrement précipité, avait été équipé d’un harnachement et d’une dignité de chevalier également imaginaires. L’exactitude de la tradition n’en est pas moins frappante, si l’on songe qu elle s’est communiquée à travers une période de mille années, et fixée à un bloc de rocher précis, entre tant d’autres.

Encore plus longue est la durée de la tradition concernant un grand tertre « Ottarshögen » dans la commune de Vendel à Uppsala en Suède. Le tertre mesure quarante mètres de diamètre, et était mentionné comme « Uttershögen » en 1670. Dans les années 1914-16, le tertre a été fouillé par un spécialiste, le Professeur Sune Lindquist, un des plus remarquables archéologues suédois. Au milieu du tertre, il découvrit une tombe dans laquelle avait été déposés une coupe de bois avec des garnitures en bronze doré, des ossements calcifiés, des pièces de jeu et les morceaux d’un peigne en os. La trouvaille est assez bien fixée dans la chronologie par une pièce d’or de la monnaie de l’empire romain oriental frappée sous l’empereur Basiliscus (476-77). La pièce ayant été utilisée comme pendentif, et assez usée, cela nous mène à proposer pour la construction de la tombe une date placée dans les premières décennies du VIe siècle. Cette époque correspond justement à celle où le roi de la famille des Ynglinge, Ottar Vendelkraka, est mort, en suivant la ligne généalogique donnée par le « Ynglingatal ». Le Professeur Lindqvist possède ainsi de bonnes raisons d’avancer que le tertre de Utter à Vendel a été la tombe d’Ottar Vendelkraka. Sous une forme plus pâle, nous voyons ici la tradition se maintenir vivante pendant 1.400 ans.

Au nord d’Oslo est situé le plus grand tumulus de l’Europe du Nord; Raknehaugen à Ullensaker. Il mesure quatre-vingt-quinze mètres de diamètre et quinze mètres de hauteur. La tradition selon laquelle un roi a été enterré là n’est pourtant pas clairement prouvée par les fouilles. L’archéologue norvégien Anders Lorange avait appris, pendant sa jeunesse d’étudiant, qu’un roi y avait été enterré entre ses deux chevaux, et ensuite recouvert de plusieurs couches de charpenterie. Avec un enthousiasme juvénile, il se mit à creuser, en descendant dans un puits étayé par des charpentes de bois, et il avait atteint une profondeur de seize pieds quand toute sa construction s’effondra. Cela advint, heureusement pour lui, à l’heure du dîner. Après cette aventure périlleuse, il commença une attaque par le côté et fut très heureux quand, du côté est, il trouva le squelette d’un cheval à soixante pieds du bord. Rien n’empêche pourtant que ne soit juste l’hypothèse alors émise, selon laquelle ce squelette proviendrait d’un cheval crevé: comme on ne mange pas les chevaux crevés, on a pu se débarrasser de lui en l’enterrant dans le tertre. Toujours est-il que le Docteur Sigurd Grieg, qui fouilla systématiquement le tertre pendant les années 1939-40, ne trouva aucune tombe. Il y avait pourtant un fait remarquable. Trois couches de charpentes se superposaient à l’intérieur, et les calculs permettraient d’envisager qu’elles avaient dû être composées d’environ trente mille morceaux de bois. L’analyse radiologique laisse supposer que le tertre doit être fait autour de la même époque que celui d’Ottar, ou peut-être quelque temps après. Mais la tradition des charpentes a été en tout cas confirmée par la réalité.

Au Danemark, on trouve des traditions encore plus anciennes, et apparemment véridiques. Jadis, les gens du canton de Bolling racontaient qu’un char plein d’or était enfoui dans le marais du presbytère de Dejbjerg. Cela paraissait incroyable. Mais quand les gens commencèrent à bêcher dans le marais en 1881 et 1883 ils ne trouvèrent pas un seul char, mais bien deux. Quoiqu’ils ne fussent pas chargés d’or leur valeur est inestimable. Ce sont des chars cultuels de l’époque pré-romaine. Des chars de cérémonie exécutés en chêne et frêne, garnis de bronze dans le style celtique. Les voitures ont été volontairement détruites et déposées dans le marais comme offrande. Dans ce cas nous avons affaire à une tradition vieille de deux mille ans.

Un souvenir norvégien enfin, qui vaut la peine d’être mentionné parce qu’il révèle une tradition purement locale qui nous ramène dans le temps jusqu’à cinq ou six mille ans en arrière. A Bömlo, au sud de Bergen, il y a un petit îlot: Hespriholmen. On trouve là une curieuse grande carrière qui date de l’époque entre mésolithique et néolithique, d’où l’on a tiré des pierres d’une qualité très fine, dense et de couleur verte. Des haches de cette carrière se trouvent répandues dans de grandes zones de l’ouest de la Norvège. Les haches étant, dans les traditions populaires, appelées des « foudres», il semble que le nom de l’îlot doive être rattaché à la période viking, et déchiffré comme « le lieu où on cherche les foudres ».

Nous constatons ainsi que l’élément traditionnel peut se maintenir vivant, attaché à un lieu précis, pendant des milliers d’années. Personne ne doit s’étonner du fait que ces éléments se trouvent embellis par l’imagination, parce que c’est justement dans la grande masse informe des traditions que l’imagination cherche ses matières premières, et les données qu elle y ramasse peuvent être combinées des manières les plus diverses. Il s’agit, dans les exemples ici mentionnés, uniquement des traditions fondées sur des unités sociales localisées, sans appui dans la cohésion traditionnelle générale. Il est évident que cette dernière est bien plus stable, beaucoup plus résistante à toute attaque, justement parce qu’il s’agit de groupements portant sur des étendues plus vastes.

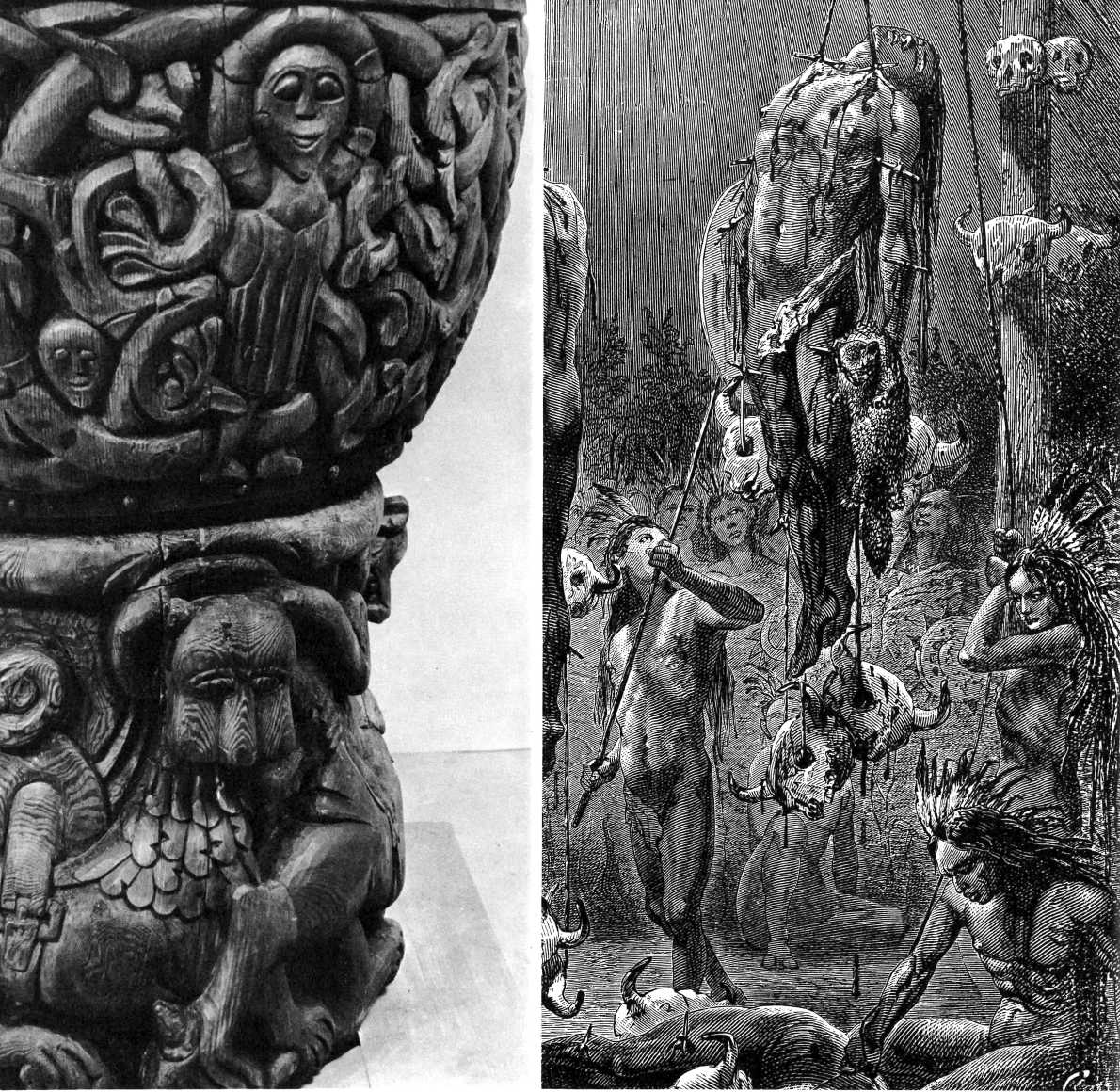

Un exemple caractéristique et important de ce genre se démontre par la situation puissante qui est dévolue à l’ours dans les croyances et la médecine populaires du Nord. L’ours possède « la force de dix hommes et l’intelligence de douze hommes. » Voilà sa renommée. Jusqu’au milieu du siècle dernier, une patte d’ours était utilisée, en médecine populaire, pour faciliter l’accouchement; et même dans notre siècle il a été possible d’obtenir des témoignages écrits au sujet de l’affinité entre l’ours et la femme enceinte, et sur ses capacités de sage-femme.

Les données archéologiques nous montrent elles aussi la position dominante que l’ours a occupé dans le Nord, comme force surnaturelle et puissance fertilisante, à partir de l’époque mésolithique au moins. Son importance dans ce domaine dès l’époque paléolithique sur le continent européen a été confirmée par les témoignages de la caverne de Montespan, en Haute-Garonne, où l’on a trouvé un ours sculpté dans l’argile, mais sans tête, avec un crâne d’ours posé devant lui entre ses pattes. Le corps d’argile portait en outre de nombreuses marques de flèches et de piques, ou d’armes semblables. Ici nous pouvons probablement poursuivre une tradition jusqu’à vingt mille ans en arrière.

Mais dans un cas pareil, il s’agit aussi d’une cohérence traditionnelle d’une énorme étendue. A partir de la presqu’île Scandinave, où la tradition a poursuivi sa vie culturelle intense et forte au moins jusqu’aux deux ou trois derniers siècles, un culte de l’ours dans des formes approchantes peut être suivi à travers toute la ceinture des forêts russes et asiatiques, à travers le détroit de Behring jusqu’en Amérique du Nord. Là on peut relever son extension vers le sud jusqu’en Californie du Sud, au Nouveau-Mexique et en Arizona. Alors que l’ours Scandinave avait une préférence pour les femmes enceintes, nous apprenons chez les Indiens du nord-ouest, qu’il existe nombre d’expériences concernant la tendance des femmes à se laisser séduire par un ours, et donc à accoucher d’un de leurs enfants.

Un autre courant de la grande cohésion traditionnelle, dans le Nord, est l’objet de l’influence indo-européenne à la fin du néolithique: l’ours y a été remplacé par le cheval comme puissance suprême de la fécondation, pour la classe supérieure des Indo-européens. Cette position a été tenue par le cheval jusqu’à la rencontre avec le christianisme, vers l’an 1000. L’effort violent par lequel la nouvelle église érigeait un tabou contre l’habitude de manger de la viande de cheval a donc été bien justifié, même s’il n’a pas connu un éclatant succès. On retrouve même aujourd’hui de nombreux fers de chevaux au-dessus des entrées d’églises, partout dans le Nord. Cette victoire du culte du cheval comme puissance de fécondité par excellence, parmi les maîtres indo-européens, n’empêchait nullement l’ours de continuer de survivre tout à son aise dans les couches non indo-européanisées de la population, ni même de s’imposer jusque dans la tradition indo-européenne. Les dents d’ours ont été d’un usage courant dans le nord de la Norvège au moins jusqu’au XIVe siècle.

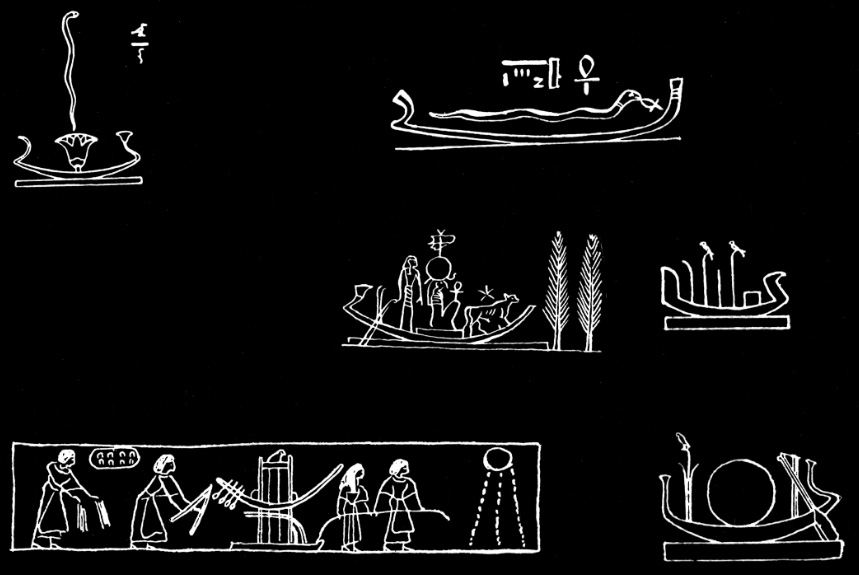

Bateau sacré égyptien, initiant la terre avant les semailles. Il est étonnant de constater le peu de cas que les savants font d un rayonnement de la vieille culture égyptienne sur l’Europe néolithique, vue l’importance exagérée que l’on donne à l’art copte pour le Moyen Age.

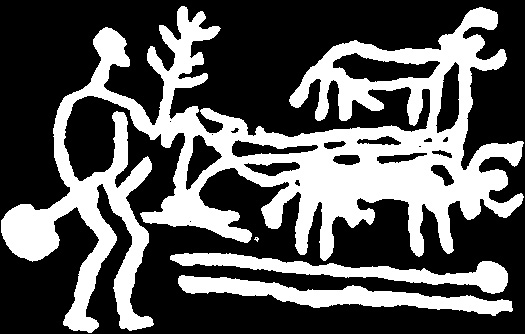

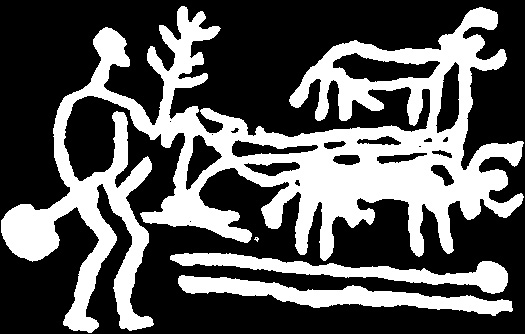

Homme à la charrue, tenant un arbre et le sac de semailles. D’après P. V. Glob. Litsleby-arden.

Il est bon d’indiquer, du reste, que cette tradition — mis à part les souvenirs paléolithiques du culte de l’ours à Montespan — ne lie aucunement le Nord avec le continent du côté de l’Europe de l’Ouest ou de l’Europe Centrale; mais le rattache à l’Europe de l’Est et au nord de l’Asie. Il a existé de nombreuses influences asiatiques dans le paléolithique ouest-européen.

La tradition de l’ours est ainsi placée dans une position qui la différencie des traditions vitales, et plus présentes, que sont pour la civilisation moderne européenne-américaine les traditions classiques et celles qui manifestent l’influence de l’ouest asiatique: les traditions religieuses et éthiques du christianisme, qui pour leur part ont été formées en grande partie par des traditions perses. Dans l’art et la pensée s’infiltrent ainsi, en plus des traditions gréco-romaines, celles des Arabes et celles de l’Inde, mélange qui apparaît encore de nos jours. Une trace assez curieuse peut être suivie dans cette ligne, entre autres dans le domaine de la terminologie des monnaies. De la pièce d’or romaine, solidus aureus, solidus survit dans le solde italien et le sou français, cependant qu’aureus a été laissé aux Scandinaves qui le gardent sous forme de öre. Le signe de la livre anglaise correspond à la libra romaine, et celui du dollar est de nouveau celui du solidus. En outre l’ancienne pièce d’argent Scandinave ort était le denarius argentus romain du temps de la république. Au Moyen Age, il s’est formé une variante intermédiaire, le ertog ou örtug.

Même si les archéologues et les historiens sont, pour la plupart, au courant de cette étrange ténacité de la vie des traditions, on a l’impression que presque tous la regardent comme une curiosité sans portée plutôt que comme une réalité fondamentale pour le plus important de la formation culturelle. Le moment semble venu où il nous faut commencer à rendre à ce phénomène sa juste valeur.

On peut légitimement considérer la cohérence traditionnelle comme une unité globale sans frontières précises, aux éléments d’une durée et d’une importance très variables. Il y a des éléments qui semblent vite disparus, à peine mentionnés. Au moment de l’événement même, celui-ci est déjà en marche vers l’unité inconsciente. De sorte que la tradition s’identifie plus ou moins avec ce qu’Emile Durkheim a appelé, à son époque, la conscience collective, dans une acception profondément révisée bien sûr. Ce que Durkheim ignorait, c’était la puissance inconsciente et subconsciente de la tradition. Pour lui, la conscience sociale était plutôt une sorte d’âme sociale de caractère individuel. C’est ce qui pense, sent et veut, même si volonté, sentiment et pensée n’agissent qu’à travers des consciences uniques, écrivait-il dans «Sociologie et Philosophie» (1925). On peut en même temps voir dans le concept de tradition une reformulation grandement modifiée de l’ancienne Völkergedanke ou pensée populaire d’Adolf Bastian, cependant que ses Elementargedanken, ou pensées élémentaires se retrouveraient, dans une formule moderne, en rapprochement avec les archétypes de Jung. Les pensées élémentaires étaient pour Bastian des idées universelles communes à l’humanité entière, idées qui à toute époque et chez tous les peuples auraient le même caractère, alors que pour lui les « pensées populaires » étaient des formes particulières, que le système des pensées élémentaires devait avoir, sous les influences diversifiantes des milieux naturels. Les « pensées populaires » représenteraient ainsi une couche de forces créatives et formantes, au-dessous des différentes formes de culture. Personne probablement n’accepterait aujourd’hui les idées de Bastian, parce qu’elles sont trop naïves et simplistes. Il est à noter que la critique de Durkheim était justement une argumentation contre les attitudes soutenues par Bastian et Wilhelm Wundt avec sa Völker**psychologie.

En laissant pour un moment de côté les questions de tradition, nous allons indiquer quelques traits de l’ancienne histoire de Normandie. Il est assez connu que le nom de la Normandie est dû aux Vikings danois et norvégiens qui ont pillé cette région vers l’an 800, et ensuite se sont fixés dans le pays. En 911, leur chef Rollo (Gange Rolv) recevait le pays en fief de Charles le Simple, et l’Etat normand s’établissait. Il y a eu des querelles entre historiens danois et norvégiens au sujet de l’importance réciproque des deux peuples dans cette entreprise; et surtout, évidemment, quant à l’origine probable de Rollo. Cette dispute est apparemment aussi futile que celle au sujet de la barbe du pape. Tout ce que l’on a pu prouver, c’est la participation de deux peuples; et le fait, indiqué par des documents, que les Vikings de Vestfold, au sud-ouest d’Oslo, ont attaqué à plusieurs reprises la France (les Westfaldingi).

On est davantage informé au sujet du développement de ce nouvel Etat normand. On connaît l’influence profonde que cette nouvelle souveraineté a eu sur la structure sociale et culturelle du pays; e t du reste, pour le développement politique et culturel de toute l’Europe de l’Ouest. Le moins important n’étant pas la saisie de l’Angleterre par Guillaume le Conquérant en 1066, ainsi que les possessions vikings dans le sud de l’Italie et en Sicile, et leur participation aux croisades. Leurs fiefs normands furent conquis par Philippe-Auguste en 1204 et soumis à la Couronne française en 1364. Ceci n’a pas empêché la Normandie de jouir à travers le Moyen Age d’une autonomie qui a donné à sa culture locale une forte particularité; ce qui s’est manifesté entre autres par l’efficacité sans pareille de son administration.

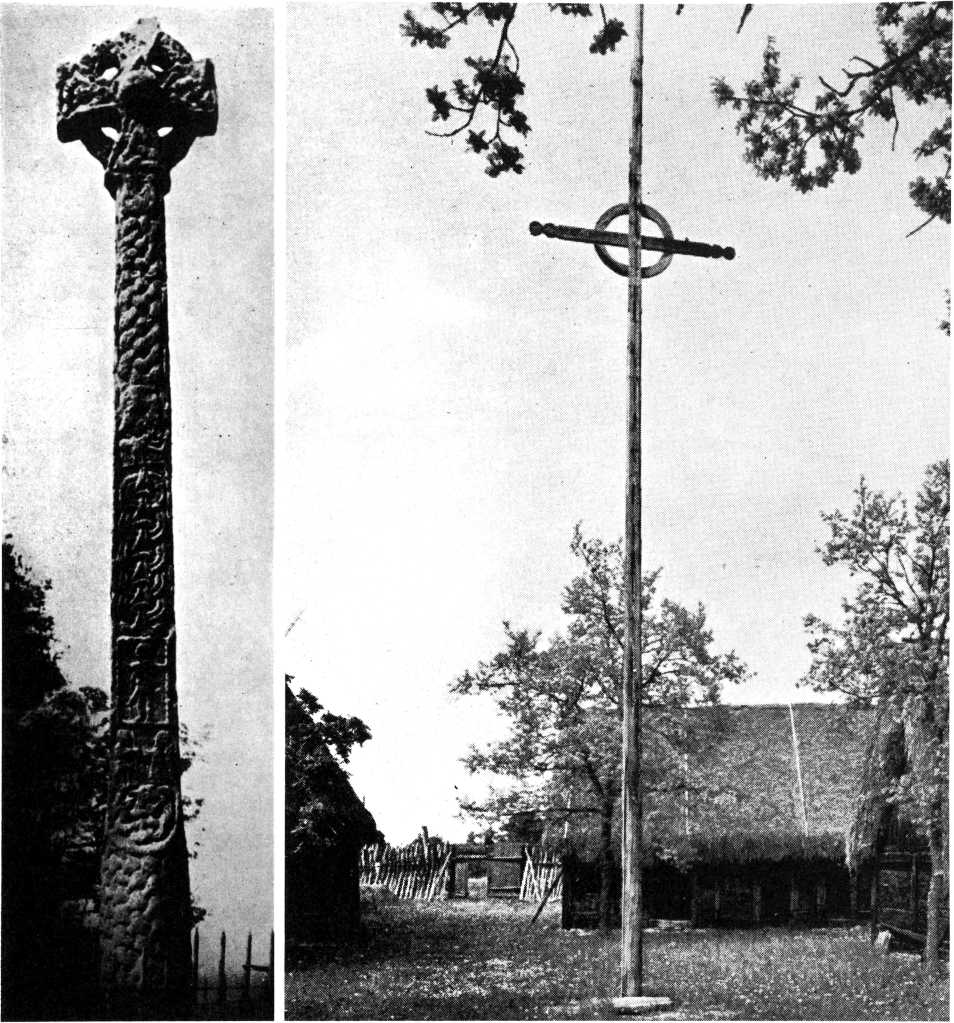

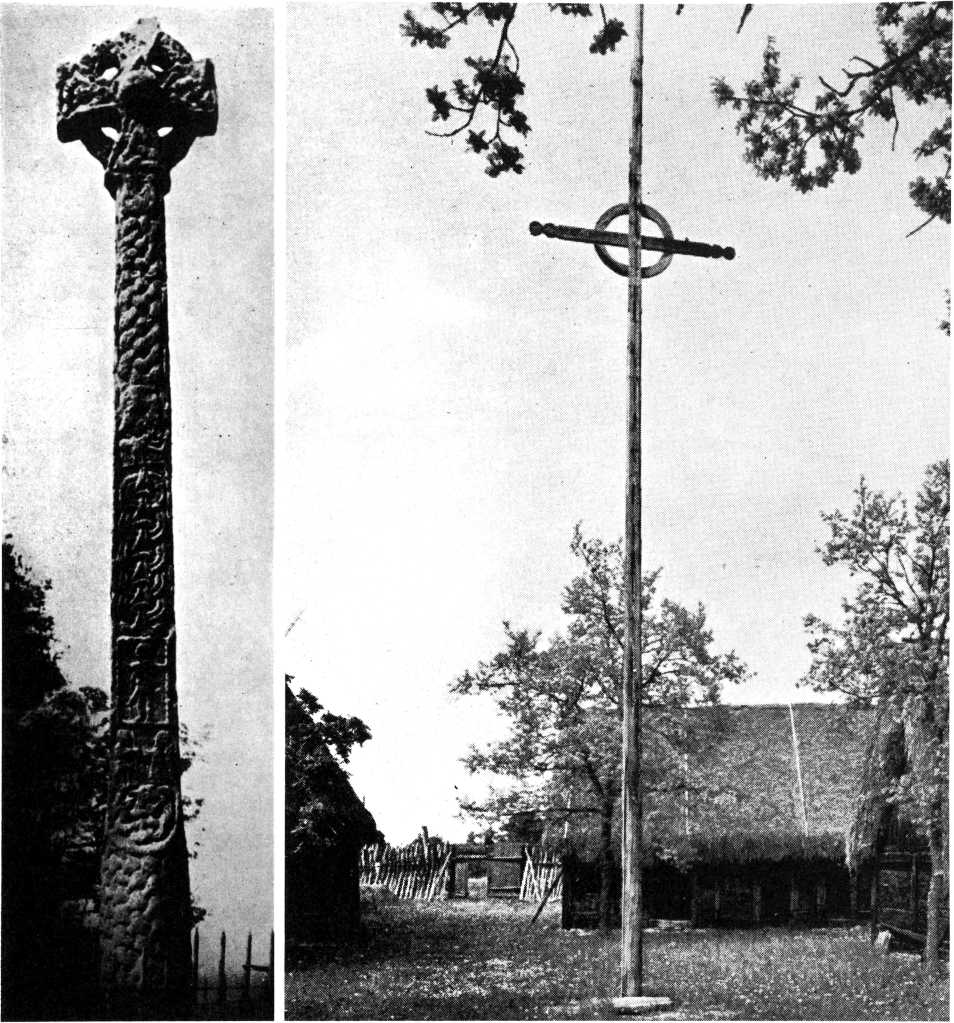

De tous ces faits, la mémoire nordique a surtout retenu les formes particulières que l’architecture romane a reçue du « style normand », lequel allait dominer l’Angleterre, et qui a propagé profondément son influence dans les pays Scandinaves.

Ce nouveau ressort n’enlève rien au fait que la tradition en Normandie a gardé de multiples éléments de ses origines nordiques, aussi bien dans le langage que dans les coutumes. Des noms de lieu comme Turville rappellent encore le dieu Tur ou Tor en qui, d’après les anciens documents de Normandie, les vikings avaient foi.

Une légende, qui trouve sa forme poétique dans un ancien poème français, conte qu’Arletta, la mère de Guillaume le Conquérant, au moment où elle l’eut mis au monde, rêva: « Il poussait un arbre de mon corps. Il se levait vers le ciel. Il jetait son ombre sur toute la Normandie ». Ceci est la copie de la légende de « L’arbre de la reine Ragnhild », l’arbre qui apparaissait dans le rêve de la femme d’un petit roi local de Norvège, Halvdan Svarte, au moment où venait de naître son fils Harald Haarfager qui devait réunir la Norvège sous son autorité. Elle rêvait qu’elle était dans son jardin, et qu’elle enlevait une épine de sa robe. Au moment où elle la tenait en main, cette épine commença à pousser, à devenir un grand arbre. L’arbre touchait terre, y prenait racine et s’élevait très haut dans le ciel. En bas l’arbre était rouge comme du sang, plus haut le tronc était d’un vert brillant, et les branches étaient blanches comme neige. Il avait beaucoup de fortes branches, certaines hautes et certaines basses. Les rameaux de l’arbre s’étendaient si loin qu’ils couvraient la Norvège entière.

Les poèmes héroïques des chants de l’Edda ont trouvé une renaissance en Normandie, et ont apporté leur contribution aux compositions de la poésie héroïque du Moyen Age français, mais en abandonnant la langue nordique, qui a été remplacée très vite par le français. Déjà le fils de Rollo, Wilhelm Langsvärd était obligé d’envoyer ses fils à Bayeux pour y étudier la langue nordique, qui avait commencé à dégénérer à Rouen. Bien plus importantes pour la tradition furent les survivances du paganisme qui, indépendamment du christianisme officiel, continait comme culte souterrain et illégal. Il troublait et apeurait beaucoup les pieuses âmes ecclésiastiques.

La mention de ces quelques survivances de l’influence nordique en Normandie est faite sans autre but que de montrer comment les traditions peuvent retenir des idées, ou du moins leurs formes symboliques, à travers des époques incalculables; et d’esquisser un peu le caractère des traces dont les Normands ont pu marquer le nouveau pays où ils s’installèrent. L’historien de la Normandie André Manguy touchait au vif quand il achevait son livre « Au temps des Vikings… les navires et la Marine Nordique d’après les vieux textes », paru en 1944 sous l’occupation allemande, par ces phrases qui semblait en vérité lancer un appel à ses « frères Scandinaves »: « apprendre à un monde renaissant tout ce que nos ancêtres entendaient par le mot aere, qui a une signification proche du mot honneur — la véritable base de la vie sociale et morale dans l’ancien peuple nordique ».

Probablement le temps est-il venu de retourner à tous ces signes, si discrets, quasi-insignifiants, gravés ou taillés aux murs des églises normandes. Mais, vu à la lumière de la tradition, il faut d’abord reconnaître le caractère synthétique, presque amorphe, de cette unité de cohérence en lent mouvement, afin de pouvoir situer les signes sur cette unité de fond dans notre essai de valorisation.

La première impression qui m’a frappé quand j’ai vu ces images était ceci: « Tudieu ! Voici toute la galerie des sujets des gravures rupestres de l’âge de bronze Scandinave ». Il est évidemment tentant d’essayer d’établir la possibilité d’une telle cohérence traditionnelle. L’idée même paraîtra peut-être à la plupart des gens relever d’un dilettantisme plus que baroque, puisque la méthode normale consiste à analyser chaque sujet pris à part, dans son isolement, et de cette facon il est naturellement facile d’expliquer que « des cercles ont été faits toujours et partout », ou des navires, ou des personnages, ou des cœurs, ou…, etc. On a bien sûr raison en ce sens qu’une telle hypothèse ne peut d’aucune façon être prouvée en suivant la démonstration classique des méthodes des probabilités. Néanmoins nous avons assez abondamment montré comme la tradition est capable d’une vitalité incroyablement tenace, et il faut retenir encore une autre condition fondamentale: quand une tradition est transplantée dans un milieu nouveau, elle est souvent marquée d’une tendance à se scléroser, à se durcir et à se refermer sur elle-même en une forme immuable. Nous en avons un exemple dans le conservatisme étonnant du langage nordique en Islande et aux Iles Foeroé. On y ressent la rupture du contact avec le lieu d’origine. L’écriture norvégienne n’a jamais été si parfaitement danoise qu’après la dissolution de l’union en 1814. Ce fut seulement après 1907 qu’elle a commencé lentement à reprendre son caractère original.

Il est incontestable qu’en feuilletant ces images on retrouve pour ainsi dire tout le répertoire des sujets des gravures rupestres de l’âge de bronze, évidemment dans une forme un peu atténuée. Ce qui caractérise avant tout les gravures rupestres Scandinaves, ce sont des sujets comme le bateau, les signes solaires, les creux en forme de coupe interprétés comme des coupes d’offrande, des chevaux, des scènes de labours, des cerfs, des serpents, des hommes dans des attitudes et situations diverses et des cavaliers, des empreintes de pieds et de mains. Tout ce monde est présent sur les murs des églises de Normandie. Il manque évidemment divers sujets des gravures rupestres, notamment le sapin — l’arbre éternellement vert — comme symbole de fertilité dont l’importance est bien entendu secondaire dans un pays aux forêts d’arbres à feuillage caduc (si l’on ne peut interpréter en tant que sapins les numéros 62, 127, 128, 131 et 178). Il manque également le char, si répandu dans les gravures rupestres. Le plus frappant dans ces relations normandes-scandinaves, c’est la ressemblance qu’il peut y avoir dans les formes mêmes de chaque signe. Ce que nous allons étudier dans nos commentaires aux images particulières.

Aucun doute n’est plus permis sur le fait que les gravures rupestres nordiques à l’âge de bronze représentent un culte de fertilité lié à l’agriculture. Le soleil prend ici une place dominante. Le soleil qui traverse pendant la nuit le ciel dans son bateau, mais qui, le jour, roule avec le cheval solaire, comme c’est exprimé de la manière la plus adéquate par le fameux char solaire de Trundholm, datant du premier âge de bronze danois.

La tradition du bateau solaire s’est visiblement maintenue dans le Nord jusqu’à une époque incroyablement tardive. Dans ma propre jeunesse, avant et pendant la première guerre mondiale, il était étrangement important pour nous, dans le village de l’ouest de la Norvège où je passais mes jeunes années, de dénicher un vieux bateau pour le placer au sommet du bûcher de la Saint-Jean. Je pense qu’il n’y a aucune objection à l’idée de considérer le feu de la nuit du solstice d’été comme une fête dont l’origine réside dans le culte solaire. Personne parmi nous ne savait pourquoi, ni ne se mettait à réfléchir pour trouver en quoi il était indispensable d’avoir ce bateau. Il devait être là, c’est tout. Il y avait certaines années où c’était une rude épreuve avant que nous arrivions à mendier assez pour avoir une vieille barque à rames pour notre cérémonie. Plus tard j’ai appris que le même jeu se déroulait dans d’autres endroits du pays.

A ce propos, il y a une étude à faire sur la question de la présence de bateaux dans les églises. L’ancienne hypothèse, qui a encore cours, selon laquelle ils représentent des ex-voto de marins oui ont survécu à des naufrages n’est pas suffisante.

Il convient de remarquer que les bûchers rituels du solstice d’été relèvent d’une tradition ancienne et générale dans le Nord. En procède celui qui se fait à l’île de Runöe dans l’ancienne Esthonie, et on prétend qu’il remonte aux vieilles influences suédoises. De telles traditions sont pour moi inconnues en Normandie, je dois l’avouer. James G. Frazer mentionne cependant dans son fameux ouvrage « The golden Bough » une étrange coutume de Saint-Lô, où une effigie humaine incendiée est jetée dans le fleuve, où elle s’en va en flottant pendant qu’elle est dévorée par le feu. Cette tradition a été interprétée (par Oscar Almgren) comme un mélange de la coutume de brûler le dieu de la fertilité sur le bûcher de l’année, et sa disparition sur la mer dans un bateau.

Grâce à son rôle important dans la marche du soleil à travers le ciel, il arrive que le cheval lui aussi prenne place entre les signes solaires, mais le cheval reste avant tout l’image de la force procréatrice. Ceci est un phénomène commun à tous les Indo-européens, bien connu dans les anciens rites hindous où ce symbolisme se présente avec une évidence extraordinaire. Le Rigveda signifie le soleil comme un disque ou une roue tirée à travers le ciel par le cheval Etaca (le leste) attelé directement au disque. Le fer à cheval qui se trouve sur deux des images dans ce livre (numéros 76 et 77) a ainsi la fonction de signifier le cheval.

Le rapport entre le cheval et le bateau se manifeste avec évidence. Ce n’est pas par hasard que dans l’ancienne Edda, dans la poésie nordique, le bateau est continuellement appelé cheval: « cheval de la mer », « cheval des ondes », etc. C’est une idée qui trouve ses origines au moins à l’âge de bronze. Une gravure rupestre à Ostfold en Norvège montre un bateau sur lequel se superposent plusieurs signes solaires. La proue est formée sans aucune doute comme une tête de cheval, avec une longue crinière flottante, tandis que l’arrière du bateau est une queue de cheval.

Le cerf aussi se présente en tant que signe solaire. Le sólarhjortr des Eddas, le signe du dieu céleste Ty. Sur une gravure rupestre de Bohuslen, en Suède, deux cerfs sont reliés par une bande, ou quelque chose de semblable, et l’un porte sur ses cornes une roue solaire. Et même cette image est parmi celles qui ont une très grande étendue.

Le signe solaire, en lui-même, est souvent une roue à quatre rayons. Des cercles concentriques aussi sont courants (cf. numéros 24 et 27). Parfois on rencontre deux cercles concentriques, avec entre eux des rayons rapprochés l’un de l’autre (cf. numéro 91). Parfois le cercle même est composé d’un rassemblement serré de creux cupuliformes (numéro 92). Il arrive qu’un personnage soit représenté avec une roue solaire en guise de tête (numéro 92). On est ici en présence du dieu solaire anthropomorphisé en personne sur l’arène des gravures rupestres. On voit souvent une ou plusieurs roues solaires passer directement au-dessus d’un bateau (cf. numéro 39), ou être tirées par le cheval solaire.

En Norvège au moins, il est frappant de rencontrer si souvent les gravures rupestres en des endroits qui s’appellent Solberg, la montagne solaire. Tout porte à croire que de tels noms sont tellement anciens qu’ils ont été attachés aux montagnes sacrées où l’on a vénéré le soleil. Les gravures se trouvent aussi en des lieux dits Helgaberg et Helgastein, la montagne et la pierre sacrées.

Les liens du culte solaire et de la fertilité de la terre sont faciles à détecter, en considérant comme les gravures sont soigneusement placées sur des rochers entourés de terres cultivables, ou sur des falaises tournées vers des morceaux de terre possédant ce caractère. Il est donc naturel que l’on retrouve souvent des scènes de labour parmi les gravures. Qu’il s’agisse de rites agraires religieux, cela est clairement dévoilé sur une gravure de Bohuslen, où le cultivateur tient dans sa main pendant son travail un petit sapin. Sa verdure éternelle était le signe de la fertilité de la terre dans de grandes régions de l’Europe. Nous trouvons souvent le sapin comme image autonome sur les gravures rupestres. Il semble même avoir survécu à sa rencontre avec le christianisme en Allemagne, où il était connu pendant toute la durée du Moyen Age, et d’où il a trouvé ensuite une renaissance étendue à l’Europe aussi bien qu’à l’Amérique du Nord, en tant qu’arbre de Noël. Même ce laboureur, nous le retrouvons ici (numéro 94). Il travaille avec une charrue à roues, utilisée de longue date à travers l’Europe. Elle a été apportée en Angleterre par les Angles et les Saxons.

Les empreintes de pieds constituent un sujet extrêmement commun dans les gravures rupestres. Les mains s’y retrouvent aussi, mais plus rarement. Nous sommes ici devant une représentation pour ainsi dire universelle, parce que les empreintes de pieds d’hommes et d’animaux se trouvent quasiment partout sur la terre, et les empreintes des mains sont au moins aussi répandues. En Europe cette représentation remonte à l’art paléolithique le plus ancien. Sans faire de commentaires aux discussions sur les interprétations qui ont été avancées pour ces signes, normalement fondées sur des conjectures, il faut quand même mentionner le fait qu’ils font tous les deux partie de l’ensemble fixé dans les sujets des gravures rupestres aussi bien que de celui des églises de Normandie (numéros 68-76, 78-83).

On rencontre de temps en temps, sur les gravures rupestres, un personnage qui a des mains énormes. On l’a nommé « le dieu aux grandes mains ». Le Docteur Just Bing considérait qu’il représentait un des deux grands dieux indo- européens, qui était « le dieu du feu » et « le dieu du ciel » (le « dieu aux grandes mains » correspondant au premier mentionné). Mais ses arguments étaient, une fois de plus, tellement fondés sur ses désirs qu’il n’y a guère de raison de les retenir. Il y a, contrairement à cela, toutes raisons d’attirer l’attention sur les étranges personnages à grandes mains, numéros 84 et 85. Le 84 présente un intérêt spécial, étant équipé en supplément d’une grande « forme solaire » en spirale sur le ventre.

Le sujet le plus répandu des gravures rupestres du Nord reste le trou en forme de coupe, interprété en tant que coupe d’offrande. Dans l’art des rochers, c est un sujet aussi répandu par le monde que les empreintes de pieds et de mains. Les trous se trouvent réunis par milliers, et souvent placés en rapport dans une composition précise. Ils peuvent former des images solaires. Il y a sur une gravure de Bohuslen une grande roue où les intervalles intérieurs sont garnis de trous serrés. Est-ce la roue céleste avec les étoiles ? Un zodiaque primitif ?

Qui sait ? Sur une gravure norvégienne d’Ostfold nous voyons une voie étroite et longue, composée de trous, qui monte le long de la montagne pour entourer un signe solaire. Est-ce la Voie Lactée ? Il ne semble pas qu’une dépendance absolue soit logiquement nécessaire entre les trous et le culte solaire proprement dit, et à tout le moins, pas directement entre eux et le culte agraire de la terre, puisque l’on trouve ces trous parmi les gravures rupestres loins en haute montagne, en Norvège, là où toute possibilité de culture est exclue ou bien, dans le meilleur des cas, aurait rencontré des conditions extrêmement défavorables, même dans le climat chaud de l’époque néolithique et de l’âge de bronze.

Un autre sujet encore, cher aux gravures rupestres, c’est le serpent. Il se trouve posé sur le bateau aussi bien que devant des hommes en posture d’adoration. Lui aussi participe du culte général du soleil et de la fécondité. Sur les calendriers de travail (les bâtons runiques) en Suède, le jour de l’équinoxe de printemps — le 21 mars — est quelquefois représenté par un serpent (Östergötland et Kalmarfief), et quelquefois par une charrue (Uppland). Cette liaison établie n’est pas dépourvue d’intérêt puisqu’une gravure rupeste de Bohuslen montre une combinaison étroite entre un serpent et une charrue. La fertilité et la mort ne sont que deux côtés d’une même chose, et dans ce rapport le serpent joue un rôle considérable dans les croyances nordiques, aussi bien que dans celles de Russie. Mais puisque le serpent fait partie du groupe des grands signes universels, son interprétation particulière sur une étendue limitée est très difficile à établir. Le rapport avec ce monde se voit sur les numéros 10, 30-31, 33-35.

Ainsi avons-nous fait l’examen des rapports étroits entre les principaux sujets des gravures rupestres nordiques et ceux des murs des églises de Normandie, ceci n’implique naturellement pas du tout qu’un rapport direct entre les deux aît été prouvé. Vu sur le fond de tout ce qui vient d’être expliqué au sujet des traditions et de leur comportement en général, il semble pourtant que nous puissions constater que tout ceci révèle pour le moins un problème dont la solution présenterait un intérêt assez considérable.

Au cas où un tel rapport direct serait soupçonné, il y a en tout cas une réserve importante à formuler. Il est absolument exclu que la philosophie religieuse de l’âge de bronze ait pu être une force spirituelle consciente dans la Normandie des XVIIe, XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Quel peut avoir été, à ce moment-là, l’interprétation consciente de ces signes ? Est-ce que par exemple le rapport entre le soleil et l’image de l’église peut être envisagé dans un but paysagiste (numéros 160-161) ? Contre cette éventualité parle le fait que le signe solaire se trouve dans des combinaisons où de telles interprétations ont très peu de base naturelle. Son rapport avec les croix indique d’autres voies d’interprétation.

Analytiquement, l’étude que je présente ici comporte deux bases d’égale importance: le principe de complémentarité mis en lumière précédemment et le concept de champ. Ce dernier a été élaboré par le psychologue américain Kurt Lewin, « Topological psychology ». Ayant pris conscience qu’aucun système socioculturel n’est un système fermé et isolé, je crois avoir suffisamment souligné la valeur dynamique de ce concept de champ. Il n’existe pas de champ clos. Il v a toujours superposition, juxtapositions, « overlappings » entre systèmes. La permanence d’un champ de tension implique l’existence de possibilités réelles de transformation et de renouvellement. La thèse que j’ai développée dans « Socioculture » (1956) nous semble être dans une optique proche de « situlogie » de M. Jorn, situlogie conçue comme une topologie dynamique ou expérimentale.

L’examen non traditionnel de la nature de la conscience intellectuelle fait apparaître l’importance du principe de complémentarité. Reprenons l’image classique de la conscience. Un phare dont l’étroit pinceau lumineux balaie successivement l’horizon entier. D’un secteur quelconque de cet horizon, et si considérable y soit la lumière projetée par l’attention, il nous serait impossible en avoir aucune image si ne demeurait simultanément présent comme à la lueur d’une veilleuse le reste de l’horizon. Complémentarité essentielle qui est inscrite dans la simultanéité même de ces deux différents niveaux de conscience, l’un précis, l’autre diffus.

UNE LETTRE…

Durant mon séjour dans le Midi, j’ai lu attentivement les deux préfaces écrites, pour le recueil de photos de graffiti, par MM. Glob et Gjessing. Or je me trouve très embarrassé pour écrire à mon tour quelque chose sur ces documents, car je ne suis pas absolument d’accord avec MM. Glob et Gjessing sur le sens qu’il convient de donner à ces documents. Il faudrait, en premier lieu, étudier leur provenance. Ont-ils été gravés sur des pierres qui ont ensuite servi à la construction de l’église ? Ou bien ont-ils été gravés alors que la pierre était déjà placée dans un mur ? Il me paraît certain que les maçons, jadis, dessinaient volontiers à la pointe sur les pierres qu’ils allaient employer, ou qu’ils venaient d’employer. Ils le font encore aujourd’hui, mais avec leur crayon de chantier. D’autre part, des gens oisifs (soldats faisant le guet, promeneurs) ont certainement aussi tracé de tels graffiti. Pour ma part, j’exclus complètement l’hypothèse d’une signification ésotérique, attestant la survivance, consciente ou inconsciente, de croyances préhistoriques ou protohistoriques. Tout au plus, dans certains cas, peut-on penser à des ex-voto frustes; il faudrait alors voir si le dessin est en rapport avec le saint patron de l’église et avec les vertus ou le pouvoir guérisseur qu’on lui prêtait.

L’hypothèse de survivances du paganisme des Vikings, alléguée par M. Gjessing, est contraire à tout ce que nous apprennent les sources historiques.

Michel de BOUARD.

Doyen

FACULTÉ DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES

UNIVERSITÉ DE CAEN

Le 15 Octobre 1963

LE VANDALISME IMBÉCILE: LA GRAFFITOMANIE

Louis REAU.

Extrait de l’Histoire du vandalisme.

Librairie Hachette, 1959.

La bêtise joue un rôle dominant dans l’éclosion d’une variété puérile, assez bénigne en apparence, mais particulièrement irritante de vandalisme, qui s’appelle la graffitomanie. André Hallays l’appelle aussi la graphomanie pariétale. Mais la graffitomanie ne s’exerce pas seulement sur les murs.

« Il existe », écrivait avec colère André Hallays, qui fut un des défenseurs les plus ardents de nos monuments en péril, « une race de vandales plus odieuse et plus bête que les révolutionnaires: ce sont les monomanes du graffito. » lnnom~ brables en effet sont les niais qui, armés d’un bâton de craie ou d’un canif, aspirent à éterniser leur sottise en inscrivant leurs noms obscurs sur les portails des églises, les faces des gisants ou les glaces des palais nationaux.

Cette déplorable manie ne date pas d’hier. Les cendres du Vésuve ont conservé à Pompéi et à Herculanum des graffitis de toute sorte: électoraux ou obscènes qui datent du Ier siècle de notre ère. Leur antiquité ne peut servir d’excuse aux graffitomanes modernes.

Que les couples d’amoureux s’appliquent à graver leurs initiales ou des coeurs percés de flèches sur l’écorce des arbres, passe encore. Mais cette menue monnaie du vandalisme n’est pas le monopole des enfants, des promeneurs sentimentaux et des touristes. Il y a le vandalisme publicitaire des colleurs d’affiches qui déshonorent par d’obsédantes réclames les sites et les monuments, la graffitomanie politique des barbouilleurs nocturnes de murs et de trottoirs: fascistes mussoliniens ou communistes staliniens qui souillent de leurs slogans indélébiles au goudron et au minium les façades des édifices publics. Une législation trop indulgente pour ce genre de dégradations encourage des abus quelle devrait sévèrement réprimer.

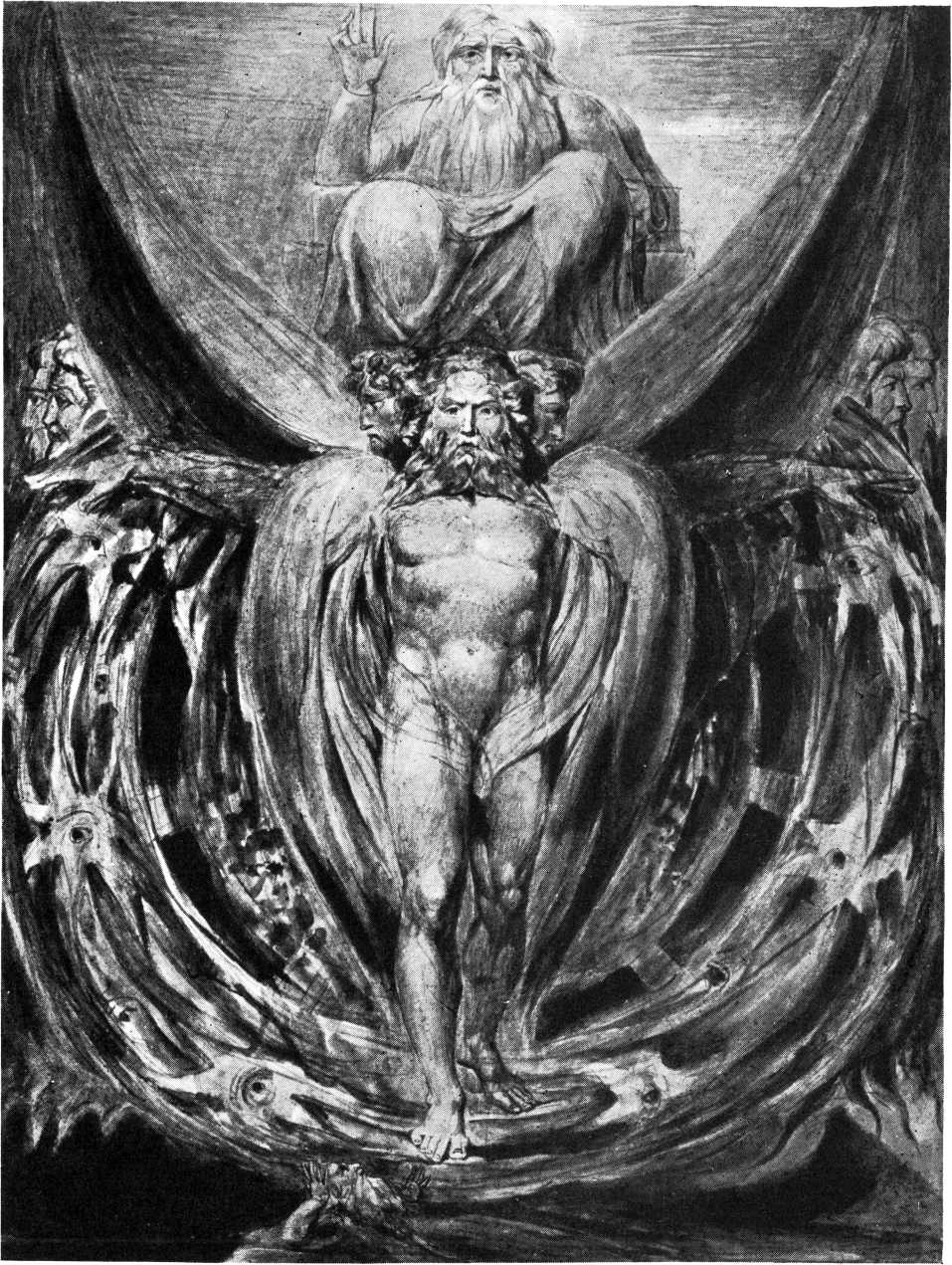

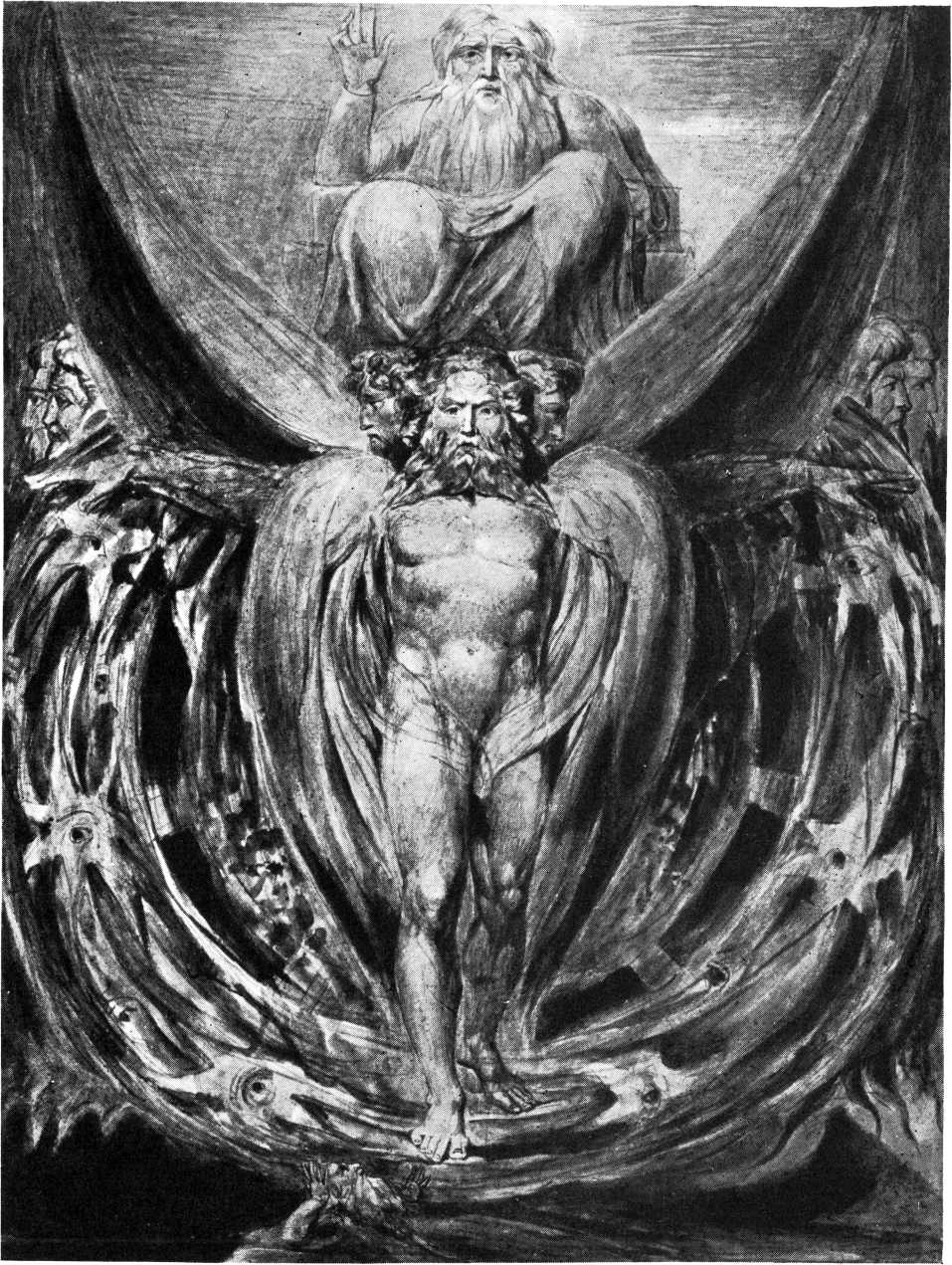

Ainsi tous les bas instincts qui sommeillent dans les profondeurs troubles du subconscient, mais qui n’attendent que l’occasion de remonter à la surface et de se déchaîner comme les « locustes » venimeuses de l’Apocalypse sortant du puits de l’abîme, tous les mauvais génies de la destruction, du pillage, du lucre, de l’envie, de la superstition et de la vengeance se partagent à tour de rôle la responsabilité des ravages du vandalisme.

SAUVAGERIE, BARBARIE ET CIVILISATION

ASGER JORN

LES NORDIQUES

Toutes les possibilités ignominieuses des comportements et des conduites humaines s’incarnent et se concrétisent en un petit nombre de situations et en quelques actes simples. Les mots qui nomment ces actes et situations élémentaires ne sont ni savants, ni nombreux. VANDALE, BARBARE, quelques autres encore, et la liste est vite close: la conscience claire ne veut rien en connaître.

Faits et mots horribles et monstrueux — tabous — la conscience les fuit, refuse à l’intelligence le droit à un libre examen, et entretient méthodiquement à leur égard une longue et persistante incuriosité. A preuve de cette dernière, un seul exemple: une fois l’inceste dénoncé et raconté, 2.000 ans se sont écoulés avant qu’on ait osé chercher et dire comment il s’enracine au cœur de l’homme.

Le seul mot de VANDALE comporte de telles implications émotives et suscite de telles oppositions horrifiées — oppositions toutes affectives — qu’il y a lieu de penser que s’en trouve épaissi le mystère même de la conduite qu’il prétend désigner. Ce mot-là est moins porteur de clarté que d’obscurité.

Aussi me paraît-il essentiel de situer enfin le vandalisme dans sa vraie lumière. Et de rendre compte, le plus exactement possible, de ce qui est tenu pour l’une de ses plus spectaculaires manifestations: le graffiti.

Orgueil d’une solidarité peut-être trop violemment ressentie ? J’ose tout de suite dire que je n’ai pas songé sans émotion, devant ces églises de la Nörmandie, aux mains patientes et laborieuses qui ont creusé, gravé, la pierre. Furtives et tremblantes également — ces mains — puisqu’il s’agissait là d’un interdit. Se plaire à imaginer qu’elles aient pu être animées par la passion la plus aveugle — celle de détruire — révèle, à mon avis, une aberration profonde. Et point seulement d’esprit mais aussi de coeur. Celle-là même prétendument ainsi dénoncée.

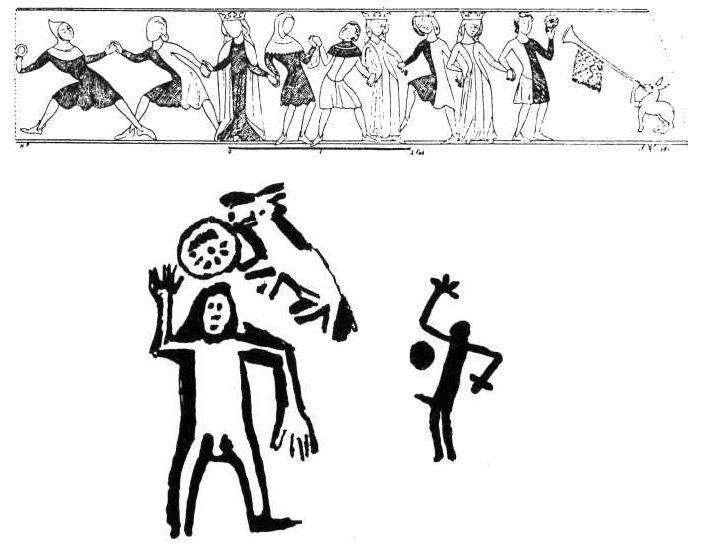

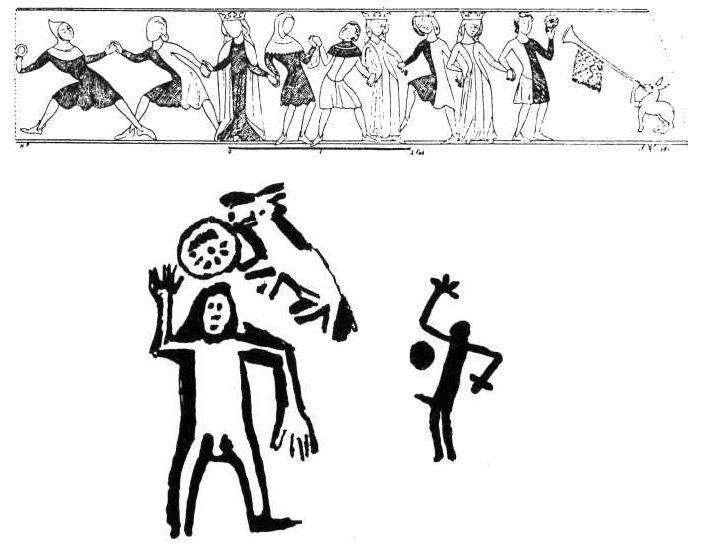

LA DANSE DE PALNA-TOKE, LE SPINN.

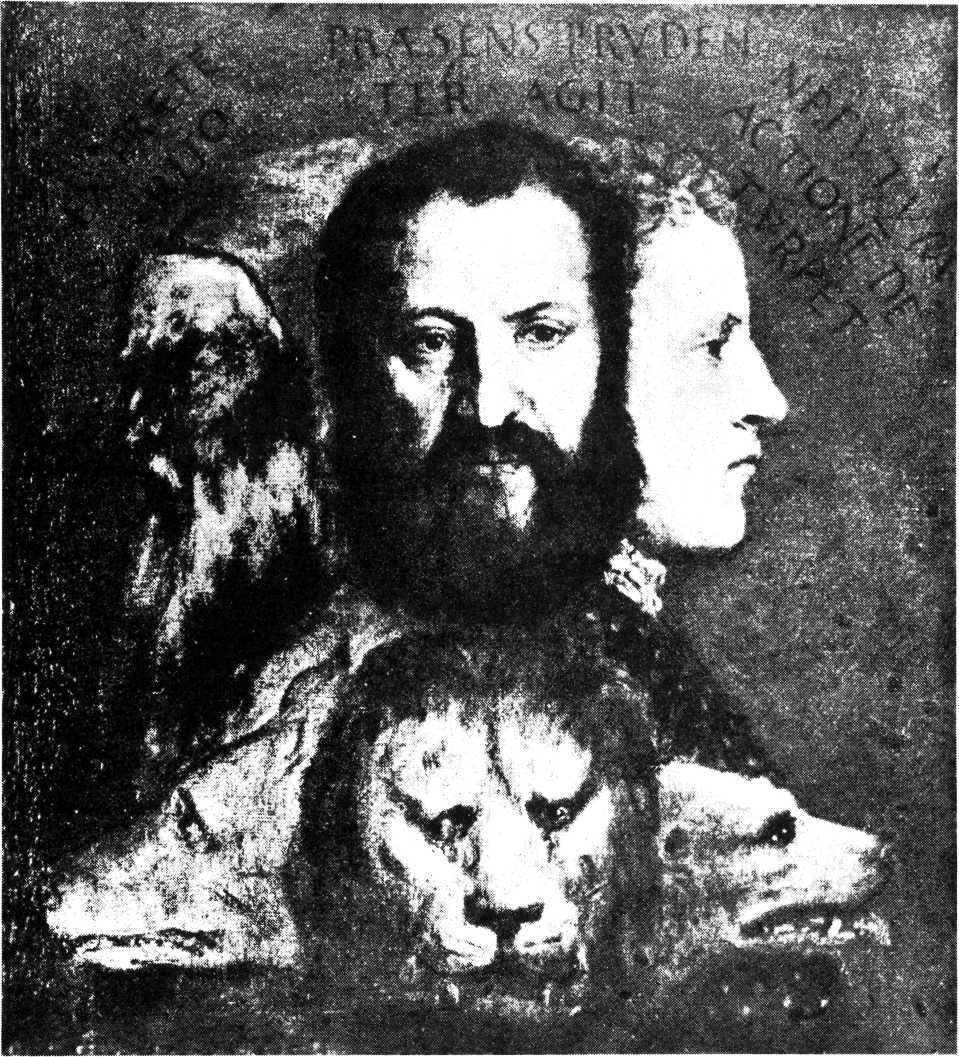

Il n’y a pas d’« archétypes » traditionnels qui ne reflètent des lois générales de la manière. Le danseur, avec un bras levé et l autre baissé ou posé sur la hanche, présente la pose classique des derviches-tourneurs. Les sculptures bogomil en Yougoslavie relient la danse à la légende de Tell, avec le flls, la pomme et l’archer.

Danseur d’Isere. La roue au-dessus de sa tête indique la rotation.

Sarcophagie Bogomil

Mais ces pierres possèdent aussi une puissance miraculeuse! Un monument des environs de Ladjevica possède la propriété de guérir. Une femme stérile qui avale un peu de poudre grattée de cette pierre deviendra féconde. Et la légende devient une croyance: Les entailles plus ou moins grandes que porte le monument, témoignent nettement des tentatives faites pour en gratter des particules. Qui sait combien de femmes ont essayé de se guérir ainsi de leur stérilité! Un monument de Donja Stupa. portant de profondes entailles, est presque enfoncé dans la terre. C’est un objet sacré dans toute la région. Ce vieux monument préserve le village de toutes les intempéries, spécialement de la grêle.

D’après Benac.

L’acte de détruire ne nous semble jamais si pur — je veux dire si absolu — que lorsqu’il met en jeu la pierre. Il nous faut bien songer qu’après avoir fait date aux âges de la préhistoire humaine, la pierre a également occupé les temps historiques, et cela sous un usage essentiellement double: construction, destruction. De l’importance de ces deux fonctions antinomiques témoignent toutes les religions: la chrétienne — pierre à bâtir et lapidation — l’islamique et d’autres, en un symbolisme moins explicité mais aussi fort. Cette dualité de son emploi est notre ambivalence même, laquelle s’est inscrite, au cours des millénaires d’abord, des siècles ensuite, dans la seule matière solide que l’homme ait connu pendant longtemps.

La présence de la pierre est chose trop fondamentale pour que nous ne soyons pas sensibilisés à sa négation, de manière extrême. Qu’elle soit ignorée — utilisée simplement comme support par les graffitomanes — ou mise bas par les vandales — voilà ce que nous ne supportons pas, ce qui nous scandalise. Et, du même coup, nous interdit de comprendre et de connaître la démarche et les mobiles de ces auteurs de signes et images gravés et dessinés; nous condamne à ne rien savoir de cette pulsion qui pousse certains hommes plus que d’autres à détruire.

Déjà d’excellents esprits se sont attachés à cesser de déposséder la conscience claire de ses moyens, à ne plus préférer stigmatiser allègrement la conduite de ce peuple du Nord — les Vandales — mais à étudier la nature d’une énergie et la signification d’un besoin — le vandalisme.

Leurs efforts ont permis la naissance de la vandalismologie.

Savoir exactement comment ont vécu les Vandales et qui ils ont été, quelles furent les épreuves, buts et difficultés de ce peuple, voilà ce qui est devenue partie du problème. Et, de manière plus centrale encore, l’étude de cette même force, rage et but: détruire, aveuglément détruire.

On a fait du mot BARBARE un mot censé désigner ceux qui, obstinément, se refusent à toute rhétorique. Pas de justification à ce fait, sinon qu’en politique, les méthodes des parlementaires nordiques s’opposent aux discours latins.

En France, au sens populaire « la barbe » est une expression qui exprime une situation ennuyeuse et désagréable. En Scandinavie, elle désigne une situation amusante et drôle.

Il est devenu possible, aujourd’hui, d’apercevoir que le potentiel affectif contenu dans le mot VANDALE est un don malheureux de la mémoire collective héréditaire. Cette mémoire même, dont la psychologie contemporaine a abondamment souligné les prouesses, s’est révélée, sur ce point précis, faillible elle aussi. En fait, la synonimie des mots VANDALE et DESTRUCTEUR masque plus la conduite qu’elle prétend désigner qu’elle ne sert ou facilite sa représentation claire. Et puis, cette mémoire ne nous aurait-elle rien transmis d’erroné que je n’hésiterais pas plus à faire la remarque suivante: tant en biologie qu’en psychologie, la faculté d’oubli et le renouvellement sont indispensables à la vie, sinon à la survie.

Science en formation, la vandalismologie a déjà ses méthodes propres et aussi son histoire.

C’est à un Français, Louis Réau, que revient le mérite de s’être efforcé de répertorier et classer les diverses variétés de vandalisme. Le définissant comme la destruction de monuments à signification historique ou à caractère artistique, il a pu opérer, à partir de ses effets, la classification suivante:

AVEC MOBILES INAVOUES:

Vandalisme sadique: L’instinct brutal de destruction;

Vandalisme cupide: Avidité aveugle de pillards;

Vandalisme envieux: Effacement de la trace des prédécesseurs;

Vandalisme intolérant: Fanatisme religieux et révolutionnaire;

Vandalisme imbécile: La graffitomanie.

AUX MOTIFS AVOUABLES:

Vandalisme religieux;

Vandalisme pudibond;

Vandalisme sentimental ou expiatoire;

Vandalisme esthétique du goût;

Vandalisme elginiste et collectionneur;

A cette classification bien diversifiée, les Anglais ont souhaité adjoindre — sous l’impulsion de Martin S. Briggs — une catégorie supplémentaire: le manque d’entretien, qui serait considéré comme un vandalisme de négligence.

Opposition vigoureuse des Français qui, personnalisant justement le débat, refusent cette ouverture possible à l’anonymat. En effet, pour pouvoir vraiment dénoncer le vandalisme, il paraît essentiel de pouvoir indiquer non seulement un acte, mais encore un agent responsable. A supposer ce dernier point non nécessaire, nous aboutirions, en pays panthéiste (ou seulement à tendance), devant le spectacle de la dégradation naturelle des choses, à une hérésie du genre: Dieu est Vandale.

Toute hérésie de ce genre engendrerait vite la tentation de se considérer soi-même comme divin. La mentalité traditionnelle de la province danoise du Vendsyssel atteste cette possibilité.

L’intransigeance des positions anglaises et la docilité traditionnelle des hommes politiques et des savants danois envers celles-ci nous font craindre que l’essor remarquable de la vandalismologie dans les années d’après-guerre ne joue, en définitive, à l’encontre même de ses buts.

L’histoire du sens du mot VANDALE est longue. Cependant c’est seulement aux temps modernes que le sens de ce mot va s’enfermer définitivement dans les clichés traditionnels que nous connaissons aujourd’hui.

En 1739, en plein siècle des Lumières, Voltaire signale la colonnade du Louvre « masquée et déshonorée par des bâtiments de Goths et de Vandales ».

Quarante-cinq ans plus tard, en août 1794, un ancien député du clergé lorrain, devenu évêque constitutionnel — l’Abbé Grégoire — l’emploie dans un rapport présenté à la Convention (14 Fructidor An III).

« Pourquoi celui-ci a-t-il choisi de clouer au pilori les Vandales plutôt que les Goths, les Huns, les Philistins ou les Béotiens ? » demande Louis Réau, qui explique:

« Les Philistins n’étaient des barbares qu’aux yeux de leurs ennemis, les Israélites; et les Béotiens ne passaient pour lourdauds que par rapport aux Athéniens. La réputation de sauvagerie des hordes germaniques était par contre bien établie dans l’Europe Occidentale, victime des grandes invasions. Les Romains gardaient le souvenir de la Vandalica Rabies, un des premiers accès de furor teutonicus dont Rome avait été victime en 445. Les Vandales avaient, quinze jours durant, saccagé la ville éternelle. »

Au cours du Moyen Age, la popularité des images de l’activité de Samson (destruction et déplacement de monuments) ne met pas en cause les Philistins eux-mêmes: Samson n’est pas devenu l’un des symboles de la lutte contre le vandalisme.

Quelles hypothèses faire sur des crimes dont aucun monument ne nous perpétue la réalité ? Pas de forfanterie vandale. A l’opposé des Romains. On connaît le monument que Titus fit dresser pour commémorer le pillage de Jérusalem — ville sacrée — et montrer l’importance du butin. Il nous serait bien difficile si les Gaulois, à leur tour, avaient détruit les monuments romains qui symbolisaient leur défaite, de nous prononcer sur leur vandalisme.

Les conquêtes et destructions napoléoniennes étaient illustrées par de courtes scènes, sur la colonne Vendôme. Mais, sous la Commune, la mise à bas de l’ennuyeuse colonne ayant engagé la responsabilité du peintre Courbet, les Français eux-mêmes ne savent pas, aujourd’hui, où est le vandale.

Qu’une nation veuille commémorer les hauts faits de son histoire par des ensembles architecturaux, c’est là un fait essentiellement, politique. Sans rapport aucun avec la réalité esthétique architecturale. Et qui n’en garantit donc en rien la valeur.

L’IMAGERIE POPULAIRE RUSSE

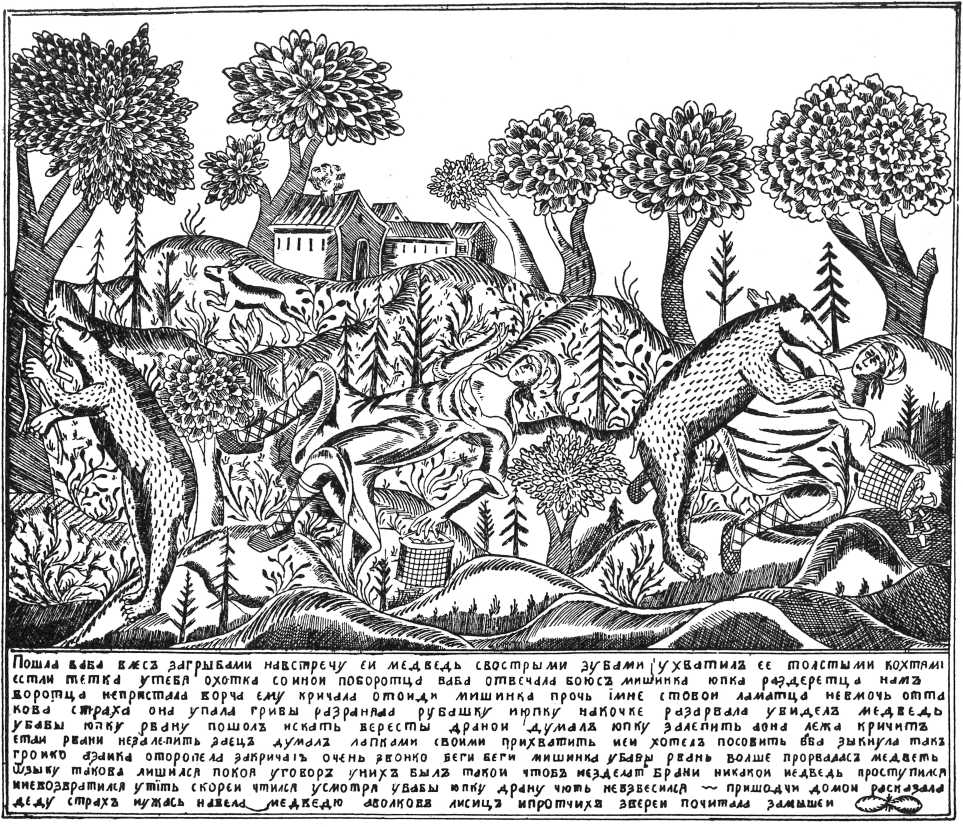

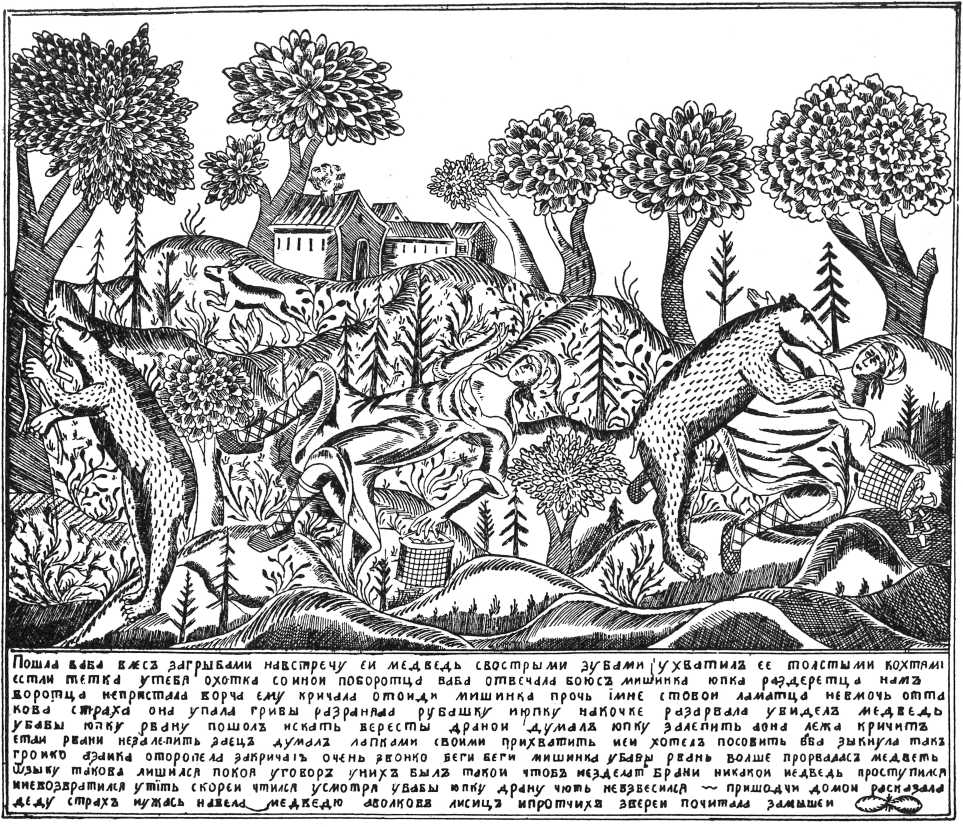

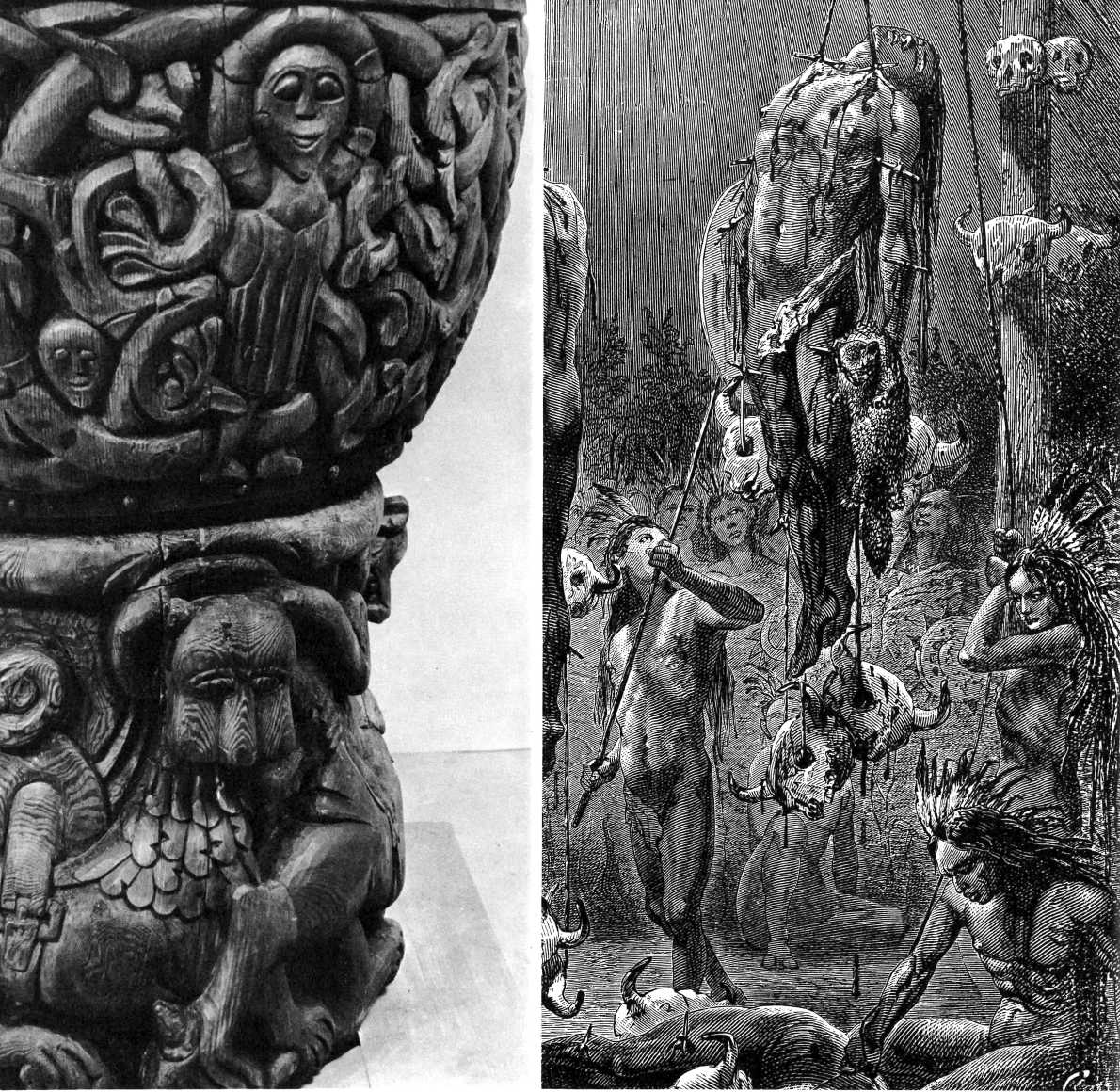

Fig. 144. L’OURS ET LA FEMME. Gravure sur cuivre exécutée entre 1820 et 1840. Dim. 285 X 330 m/m.

« Une femme est allée chercher des champignons dans le bois — un ours aux dents aiguës vient à sa rencontre, il la saisit avec ses grosses griffes. « Veux-tu, petite mère, lutter avec moi? » La femme répond: « J’ai peur, petit ours, de déchirer ma jupe. Il ne nous convient pas de lutter ensemble». Elle lui cria: «Retire-toi, ours, je n’ai pas la force de résister.» Elle succombe de peur, elle est décoiffée, elle déchire sa chemise et sa jupe contre une grosse motte de terre. Quand l’ours vit la jupe de la femme déchirée il alla chercher de la ficelle — il pensait boucher le trou de la jupe avec une lanière d’écorce, mais la femme couchée à terre crie: « Tu ne pourras pas reboucher cette déchirure. » Le lièvre avait l’intention de lui venir en aide et de fermer la déchirure avec ses pattes, mais la femme poussa un cri si aigu que le lièvre eût peur et cria très fort: « Cours, cours petit ours, la déchirure de la femme est devenue plus grande.» En raison de ces cris, l’ours n’eut plus de repos. Il était convenu entre eux, pour qu’il n’y eut pas de dispute, que l’ours tâcherait de partir au plus vite et ne reviendrait plus. Quand il vit la jupe de la femme déchirée il devint presque enragé. En rentrant, la femme raconta au grand-père la peur qu’elle inspira à l’ours. Les loups, les renards et les autres bêtes n’étaient plus à ses yeux que des souris.» Ce texte assonancé comporte bien des obscurités. Les intentions érotiques que l’on devine font penser à l’histoire racontée, elle, d’une façon fort claire par Rabelais.

On ne compte plus le nombre de héros dont la mémoire est desservie par la statuaire qui veut les honorer, et l’on sait des villes entières dont l’architecture et la statuaire sont de monumentales erreurs, sinon horreurs.

Par ailleurs, l’instinct grégaire n’engendre pas obligatoirement goût et sens esthétique. Le rôle civilisateur des villes n’est ni évident, ni absolu. Il s’ensuit que la destruction partielle ou totale d’un ensemble urbain ne constitue pas nécessairement un acte de vandalisme.

Mon enfance au pays d’origine des Vandales et des Teutons m’a laissé des souvenirs clairs. Je me rappelle qu’y était réputée satanique l’activité noire des grandes cités industrielles. Et je n ai pas oublié les histoires qui nous étaient contées — Sodome et Gomorrhe; et encore: la Tour de Babel. Toutes histoires en lesquelles Dieu était présent; et au travers desquelles s’exprime un état d esprit et aussi bien une position morale, dont il me semble en tant qu’artiste essentiel de retrouver les raisons et le bien-fondé plus que de s’y opposer de façon aveugle et catégorique.

Louis Réau rend un hommage sans réserve aux Romains pour leur colonisation de la Gaule — « une œuvre de civilisation, dans le sens le plus noble de ce mot » mais il change ensuite radicalement de position envers les envahisseurs nordiques, particulièrement envers les normands. Et quand alors il s’interroge sur ce qui peut être porté à l’actif de ceux-ci, il ne découvre qu’une seule chose: « la naissance de l’architecture romane que les Anglais préfèrent appeler, non sans raison, le style normand ». Rappelons en passant que ce style normand parut aux humanistes de la Renaissance italienne, d’une laideur indescriptible — un phénomène barbare, « gothique ».

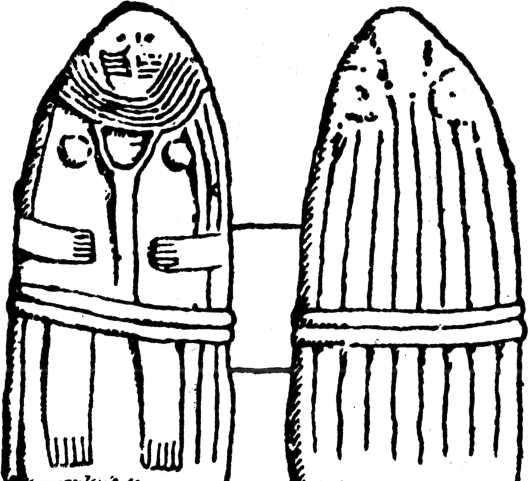

« Les chrétiens mangent Dieu par amour pour la divinité, ils communient en théophagie. Les humanisphériens poussent l’amour de l’humanité jusqu’à l’anthropophagie: ils mangent l’homme après sa mort, mais sous une forme qui n’a rien de répugnant, sous forme d’hostie, c’est-à-dire sous forme de pain et de vin, de viande et de fruits, sous forme d’aliment », explique l’anarchiste Joseph Dejacque. Témoignage de l’esprit cyclique qui domine l’anarchisme, et correspond étrangement à l’esprit agraire du néolithique. Là se trouve l’origine des rituels de l’hostie, dans les cultes de la dernière gerbe, sujet de plusieurs menhirs, supposée contenir la puissance entière de fécondité du champ. L’homme travesti en dernière gerbe était offert, considéré comme dieu, et assurait la fonction du bouc émissaire chez les bergers. »

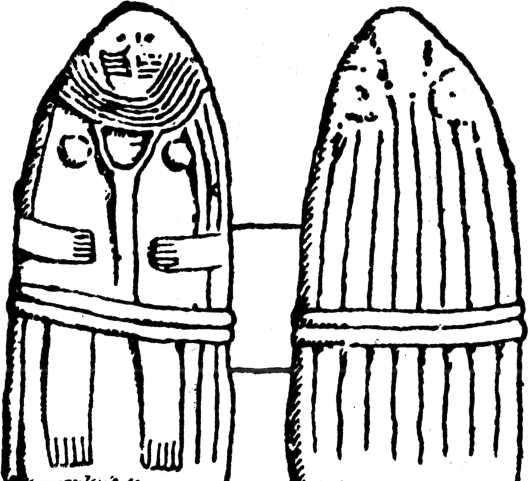

Homme revêtu d’une gerbe de blé à l’occasion de la Fête des moissons (Suède).

Face et dos d’un menhir représentant le même sujet: Rodez, Musée Fenaille.

LE VANDALISME EGLISOPHAGE

Il y eut, à Byzance, un très important vandalisme religieux — vandalisme que Louis Réau n’est parvenu qu’imparfaitement à distinguer et à isoler. Certains prêtres grattaient les icônes, en détachaient des parcelles qu’ils recueillaient dans un calice, à dessein de faire communier les fidèles. Ces icônes — sommets de l’art religieux de l’époque — furent ainsi véritablement livrées à la consommation.

Ce fétichisme de l’absorption fut cause que le sens et la signification de l’art s’en trouvèrent changés et obscurcis.

Pour arrêter ce vandalisme de la nutrition devenu rituel, l’Empereur décréta l’iconoclasme; tous ceux qui possédaient, de manière privée, des icônes, étaient invités à venir les apporter à Constantinople où, en place publique, elles étaient brûlées. C’était évidemment palier à un vandalisme par un autre: celui du sacrifice, du potlatch.

Cependant ce vandalisme gouvernemental ne peut être comparé au premier — populaire.

Dans le premier cas, il s’agit d’une fête. Cette consommation — si naïve fut-elle — comportait d’authentiques éléments d’amour et de foi: c’était le vandalisme heureux.

P.V. Glob nous rapporte, entre autres cas, celui d’images-gâteaux dont l’absorption parfaite impliquait destruction d’êtres humains, donc un certain cannibalisme. L’anthropophagie relève plus précisément du teutonisme dont elle dévoile, aberrante, la volonté de pureté et d’esthétisme. Et ce sont les aberrations de cette volonté qui se retrouvent dans le domaine vandalique — domaine où les données historiques nous obligent à établir de semblables catégories.

Emile Male dans son ouvrage « La fin du paganisme en Gaule », nous informe de la célébrité — dans la France médiévale et nordique — de la tombe de l’évêque mérovingien Saint-Drausin. Cette tombe, aujourd’hui conservée au Musée du Louvre, était originairement en l’église Notre-Dame à Soissons. Séjournaient près d’elle les chevaliers qui allaient combattre en champ clos et saint Thomas de Canterbury, sur le point de retourner en Angleterre où il savait devoir affronter Henri II, y fit veillée d armes. Venant en pèlerinage, les fidèles avaient coutume d’emporter quelques parcelles du couvercle, qu’ils diluaient dans l’eau et faisaient boire aux malades. Cette coutume, qui s’est poursuivie pendant des siècles, a fait disparaître presque complètement le couvercle. Celui que l’on voit actuellement au Louvre n’est pas l’original, mais un autre qui est Wisigoth et provient de l’église de Saint-Germain- des-Prés.

En Espagne également, les tombes des rois Wisigoths montrent les traces d’une même activité.