10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art

10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art is the title of Asger Jorn’s ambitious but unfinished encyclopedic project to document the visual history of Scandinavian art from prehistory through the Middle Ages, conceived through his Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism. Jorn planned the series as 24 to 32 volumes presenting Nordic folk art through large-format photography, with images taking precedence over text—a deliberate reversal of conventional art historical practice. The photographic work was carried out primarily by Gérard Franceschi between 1962 and 1965, resulting in an archive of approximately 25,000 negatives. Despite this vast documentation effort, only one volume was published during Jorn’s lifetime, with several more completed posthumously based on his image layouts.

Background

The project grew out of Jorn’s long-standing conviction that Scandinavian visual culture had been systematically undervalued. As he wrote in his foreword to the series, “there exists no comprehensive work on the art of the Nordic past, and this absence has given the outside world the impression that we Northerners are an unartistic people.” Shortly after resigning from the Situationist International in 1961, Jorn founded the Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism (Skandinavisk Institut for Sammenlignende Vandalisme, or SISV) together with archaeologist P.V. Glob, Werner Jacobsen of the National Museum of Denmark, and Holger Arbman of the University of Lund.

Jorn had been inspired by André Malraux’s Musée imaginaire project, which used photography to create a universal art history. However, where Malraux sought universality, Jorn strategically emphasized the distinctly Scandinavian as a form of resistance against dominant classical-Latin artistic traditions. He hired Gérard Franceschi—who had served as chief photographer at the Louvre for Malraux’s project—to lead the photographic documentation. As Glob noted in his introduction, the collaboration between artist and scholar had roots going back a quarter-century to the wartime journal Helhesten, “in which they sought to demonstrate the interplay between the visual arts and other aspects of cultural life, including archaeology and ethnography.”

As Guy Atkins recounted, the idea of documenting the history of early Scandinavian art had “haunted” Jorn for twenty-five years. Jorn had been “trying, in vain, to persuade various art foundations, ministries, and art scholars in Scandinavia to collaborate with him—on his own terms—in a series of publications under the general heading ‘10,000 years of Nordic folk art’.”Guy Atkins and Troels Andersen, Asger Jorn: The Final Years 1965–1973, Borgens Forlag, Copenhagen.

As has been emphasized from the first time this project was discussed, this concerns the production of a series of picture books with a brief orienting text. The purpose is, through the best possible reproduction technique, to produce a series of art books in this word’s most elementary meaning, books that can bring joy to any person who is interested in art. They have absolutely no didactic or educational purpose.

- Asger Jorn, Plan for the Working Process, May 1964

Method

Jorn’s approach, which he called “comparative vandalism,” involved separating artworks from their original contexts through photography, allowing them to be compared and juxtaposed in new configurations. The term was deliberately provocative, positioning Nordic artistic traditions—which he associated with the Germanic tribes including the Vandals—as a non-canonical, anti-classical alternative to established European art history.

Jorn insisted on complete artistic control over each volume’s image arrangement. Authors could suggest essential images but could not exclude images belonging to the subject area. He reserved the right to arrange images “absolutely undidactically according to purely artistic requirements to make the book as such into a unified artwork.” In this way, Jorn’s contribution to each collaborative volume was the visual composition itself.

As archaeologist P.V. Glob explained in his introduction to the series:

There is no shortage of major works and smaller essays concerning Nordic prehistoric and medieval art, but often the presentation of this world of images is merely an account of stylistic development, connections with contemporary European art, chronology and technique. Here we wish to take a different path, letting the images speak for themselves, accompanied only by an introduction and by the necessary facts about the depicted artworks.

This path is passable because the artist and the scholar have joined forces. Thus, the artist selects and compiles the internal connections between the images in the group to be treated, gathering these images into a continuous collage, so that they can be seen both individually and in context, while the scholar provides them with the necessary documentation.

- P.V. Glob, Introduction to 10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art

Published Volumes

Jorn’s insistence on artistic control brought him into conflict with the scholarly establishment. As Atkins described it, “Jorn’s private war against officialdom centred on the question whether he—an artist—was best qualified to be in charge of the programme, or whether the editor-in-chief should be an established academic, such as Professor Glob.” Jorn argued that previous studies of Viking art had treated the images as a minor appendage to the text, whereas he insisted that the images should take precedence. The dispute ultimately led to a breach between Jorn and his old friend P.V. Glob, and by 1965 the Institute had become, in Atkins’s words, “a source of controversy and annoyance” to Jorn.Guy Atkins and Troels Andersen, Asger Jorn: The Final Years 1965–1973, Borgens Forlag, Copenhagen.

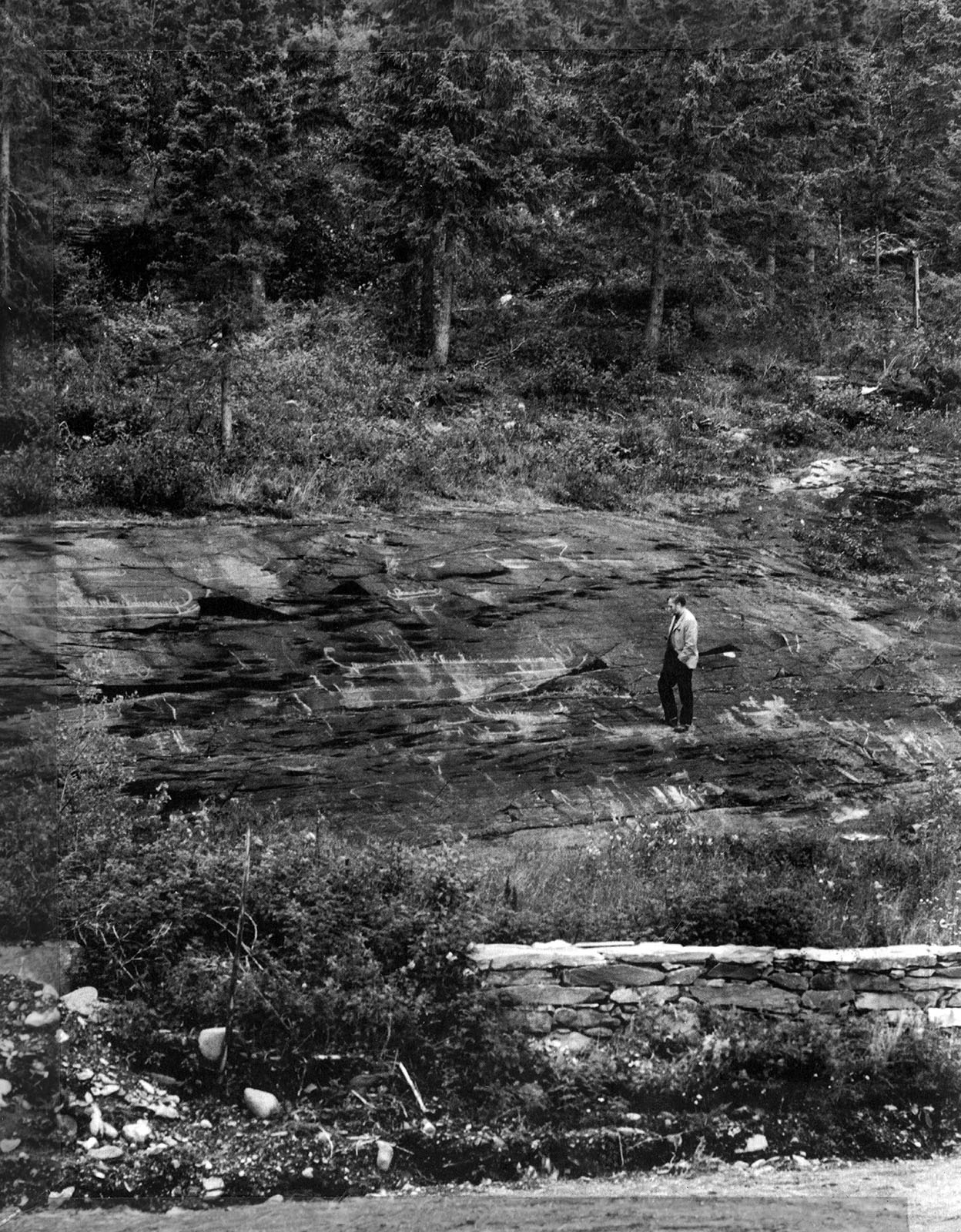

To prove his point, Jorn published at his own expense a pilot volume of great beauty on the stone sculpture of southern Sweden. Atkins described how Jorn “had used a top-ranking photographer whose camera work he directed, somewhat after the manner of a film director, in order to achieve the best angles and lighting for each subject.”Guy Atkins and Troels Andersen, Asger Jorn: The Final Years 1965–1973, Borgens Forlag, Copenhagen. This was Skånes stenskulptur under 1100-talet (1965), a study of 12th-century stone sculpture in the Skåne region written by Erik Cinthio, published in a private edition of 120 numbered copies bearing the restriction that it “cannot be sold, reviewed or enter public libraries.”

When negotiations with Skandinavisk Forlag in Odense finally broke down—the publisher having demanded the series be run by a committee of scholars, with Jorn holding only one vote—Jorn at least had “one consolation: he could now pursue his ‘vandalist’ hobby unmolested. He might even be able to devote more time to painting.”Guy Atkins and Troels Andersen, Asger Jorn: The Final Years 1965–1973, Borgens Forlag, Copenhagen.

Several further volumes were completed posthumously by Tove Nyholm and others based on Jorn’s image layouts and notes, published by Borgens Forlag in collaboration with Silkeborg Kunstmuseum. These include volumes on Nordic golden images of the early Middle Ages, Greenlandic folk art, Norwegian stave churches, and Nordic Iron Age animal art. The Nordic Iron Age volumes were published with support from Augustinusfonden and Ny Carlsbergfondet.

Legacy

Following Jorn’s death in 1973, the SISV became a sort of “imaginary museum,” with its photographic archive housed at Museum Jorn in Silkeborg. The archive of approximately 25,000 images represents one of the most comprehensive photographic documentations of Nordic medieval and ancient art ever assembled, though the vast majority remains unpublished.

The project and its archive have attracted renewed scholarly and artistic interest. In 1995–96, the exhibition “Asger Jorn and 10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art” at the National Museum in Copenhagen and Silkeborg Art Museum presented the first major survey of the project’s legacy. In 2001, Pontus Hulten curated “The True History of the Vandals” at Vandalorum in Värnamo, and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm presented “Comparative Vandalism” based on Jorn’s photographic contact sheets from his 1964 journey to Gotland.

The project’s incompletion paradoxically reinforces Jorn’s anti-authoritarian approach to knowledge production. The massive archive of decontextualized images, freed from definitive scholarly interpretation, remains open to continual reordering and reinterpretation—embodying the “vandalist” approach to art history that Jorn championed.

Articles in this collection

3 articles in this collection.

Asger Jorn and 10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art

Asger Jorn and 10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art is an exhibition catalogue and documentation of Asger Jorn's ambitious but unfinished project to create a 32-volume encyclopedic visual survey of Nordic art from prehistory through the Middle Ages, published in conjunction with exhibitions at the National Museum in Copenhagen and Silkeborg Art Museum in 1995-96.

Scania's Stone Sculpture During the 12th Century

Scania's Stone Sculpture During the 12th Century is a book on 12th century stone sculpture from the Scania region of southern Sweden by Erik Cinthio, with an introduction by P. V. Glob and notes by Asger Jorn.

The Bird, the Animal and the Human in Nordic Iron Age Art

The Bird, the Animal and the Human in Nordic Iron Age Art is the second volume in Asger Jorn's posthumous series 10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art, featuring photographs by Gérard Franceschi and text by Norwegian archaeologist Bente Magnus examining animal symbolism in Nordic Iron Age art.